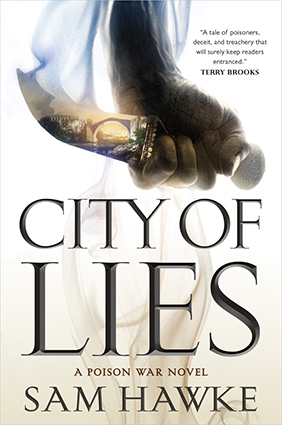

opens in a new window Welcome to #FearlessWomen! Today, debut author Sam Hawke tackles a big question: how does science fiction and fantasy uniquely explore gender, and specifically, how does she explore gender in City of Lies?

Welcome to #FearlessWomen! Today, debut author Sam Hawke tackles a big question: how does science fiction and fantasy uniquely explore gender, and specifically, how does she explore gender in City of Lies?

Cultures have a lot of inbuilt norms and expectations and assumptions. Some of the deepest and most pervasive relate to gender: what it is, what it means, what roles we assign to it. Of course, cultures aren’t monolithic and generalisations are just that. No matter how rigidly a society purports to enforce gender structures, people being people, you can be sure there’ll be beautiful variations bursting out of the cracks every time you turn your back. But there’s no escaping the reality that if someone acts outside expected roles in an established culture, the culture pushes back. So in writing about an established, real world culture, you have a choice between engaging with and challenging cultural assumptions, or accepting and working your story within them.

In SF/F, you get a third option: you can just fuck all the ‘rules’ right up.

You can tell a lot of important stories that examine gender by having characters be outsiders or insiders who push against the status quo; you can help readers think through their own cultural assumptions or see themselves and their experiences reflected in a different world. Of course there is a long tradition of stories featuring female protagonists who long to escape the shackles of the role society has assigned them: the Eowyns, Alannas, and Arya Starks of SF/F are a well-established feature in the genre (less common, though, are their male counterparts who rarely strive the freedom to engage in what Western societies tend to think of as ‘feminine’ pursuits—Vanyel from Mercedes Lackey’s Last Herald-Mage novels is the earliest example I remember reading).

Modern SF/F offers more nuanced takes and a chance to explore the effects of fixed gender expectations on people who don’t fit within the cishet mould those structures are built around. Gene/Micah Grey in Laura Lam’s Pantomime is an intersex character raised female in a strict Victorian-esque world who runs away from a family’s planned non-consensual surgery to perform in a circus as male-presenting. Breq in Ann Leckie’s lauded Ancillary Justice deals with linguistic and cross-species gender identification issues, coming from a culture that does not use gendered pronouns and attempting to deal with a (human) society which does. And confronting and understanding the Fool’s gender fluidity in a traditionally patriarchal-styled society in Robin Hobb’s Realm of the Elderlings series presents ongoing and significant emotional challenges and growth for Fitz. SF/F is full of wonderful examples that turn a mirror on our own understanding of gender and ask us to look closer.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want to write about the conflicts inherent in these scenarios, about the challenges and the macro and micro aggressions faced by people outside the cultural ‘norm’. Instead, you want to upend them and explore a world without them. SF/F gives us the power and permission to start from the beginning and ask: wait, but why? Or, on the flipside: why not? What if men had been wiped out and women were able to reproduce asexually (Nicola Griffith’s Ammonite)? What if you could take on male or female appearance at will (Imajica by Clive Barker)? What if the gender of your protagonist was so unimportant to the story that you didn’t even need to disclose it (John Scalzi’s Lock In)? There’s no limit to the questions you can ask when your genre is (literally) defined by speculation. What if no-one cared to assign gender to children, leaving people were free to self-determine at their own pace? Why would a society limit its access to half the population if it was in need of certain skill sets or talents? (Most jobs don’t require genitals, after all). Playing with these assumptions can lead you to some great fun worldbuilding adventures into linguistics, history, the influence of environmental factors, religion… SF/F can explore these questions in a way that a story set in the real world can’t.

In City of Lies I wanted to play with our assumptions about family structures, and particularly how they intersect with romantic relationships. History is full of examples of conflicts built around patriarchy—women being blamed for fertility issues (hey dudes, around half the time it’s you, not her!), a child’s social value being determined by reference to the social rank and importance of the father, value judgments about the acceptability and respectability of certain relationships (heterosexual marriage) over others, and, critically, inherent uncertainty about the identify of fathers which creates risks for women. These factors underpin a lot of the cultural baggage Western societies carry about gender and acceptable behaviours. I didn’t want a bar of it. There’s enough toxic masculinity in Real World 2018™ and I didn’t want to create a fictional mirror of that.

Instead I envisioned a society which prioritised and valued blood family relationships over romantic and sexual ones. If we were socialised to treat our blood relatives as the natural ‘village’ to parent our children, the identity of the father of a child inherently diminishes, and therefore the value that society places on establishing long term couple relationships likewise diminishes. What would a society without marriage, without expectation that children leave their family home as adults, look like? How might it have developed? What would this change about how we treat each other, particularly in relation to gender and sexuality? Importantly, while I had a lot of fun with this as a worldbuilding exercise, and it gave me the society as a backdrop that I wanted for my brother/sister protagonists, it’s not the point of the story. It’s just there. SF/F gives us the freedom to write a book about poison and treachery and old magic in which it also just happens that women are regarded as equal humans whose contribution to their society is judged by their skills and talents, not their value to a man, and that’s such an obvious baseline that it doesn’t need to be a plot point. Imagine that.

Order Your Copy of City of Lies

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Follow Sam Hawke on Twitter ( opens in a new window@samhawkewrites), on opens in a new windowFacebook, and on her opens in a new windowwebsite.

So many people who are drawn to the unusual and the alien wind up reading SF/F, it’s brilliant to see our being explored and contrasted in so many books these days. Fantasy has always been a gateway to examining ourselves and the world we live in. It’s heartening to see that tradition continued, I for one am eager to read City of Lies. Good article. (y)

The first book I ever read that really brought the idea of gender fluidity to me was Ursula le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness. I was a member of the Sci Fi book club, I was 13 and yes i was fearless. I had just toured Europe with my family, and found my first Issac Asimov book at a train station (only English one there too!) , Nine Tomorrows. But my mind was officially blown. By Ursula, even though I might have seen it coming in her Wizard of Earthsea series.

I just ordered your book. I can hardly wait to start reading it. I wish it was getting to me before the 4th of July so I could have the whole day to read it. I ordered the hard cover.

FB: https://faceboom.com/branwen.drew

My artist page: https://www.facebook.com/BranwenDrewArtist/

Spending more time doing homework about History/social before uttering “facts” totally wrong would do a lot of good.

– Fertility is food dependent. When lacking regular food women start to have irregular menstruations, so lower fertility. They can even stop until the situation gets better. It happened a lot of during Human history.

– Egypt -3000BC to -100BC, often peace time, few external invasions, food not scarce: life expectancy for a man 30-35, for a woman 20-25. Huge childbirth death rate, heavy chance for the mother to die hence the abysmal 20-25.

On some recorded families during the New Kingdom, nearly 400 years of records, 30% children born do not reach 10 yo.

To compensate, lot of children, more risks for the women. Blood Family: Nothing is more important than the children who survive. They are expected to provide for the parents later too.

Lot of Goddess/Gods dedicated to protect the fertility, the mother, the child, to look upon the childbirth.

Many “beauty” names are built like “godname-wants him/her to live” or “godname-says that he/she will live”. Example: Djedkhonsuiufankh meaning “Khonsu says that he will live” usual and daily use: Djekhy.

If the stage of 25-30 yo is passed a huge chance to live a relatively long life. 50-60 yo are not rare.

I could go on but the the summary is: For most of the human history people had not access to 3-4 meals by day and a doctor reachable with a phone call.

I do not say it was good. I do not try to justify anything. I just say than we live in a hugely improved time where human specie does not depend on chance to go on and women are freed from that burden. It becomes a choice and that is good.

I would love fantasy writers to stop antagonize the past but to do a real worldbuilding. What does it mean when you have magic which can heal in a low tech world? Does it break the chains of the women and allow them to have the choice women of today have or not? Would it free them in some countries but not everywhere (as in our current world)? RPG since the beginning (D&D) have gender change magic. What would be the impact? Would it create a new from of crime or new sort of punishment, or new sort of forbidden practice somewhere?

What if there is no magic of this kind and you want to have your women free and not tied to the burden of reproduction? How would the society have evolved to allow that? What kind of social mechanism? And so on..