opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

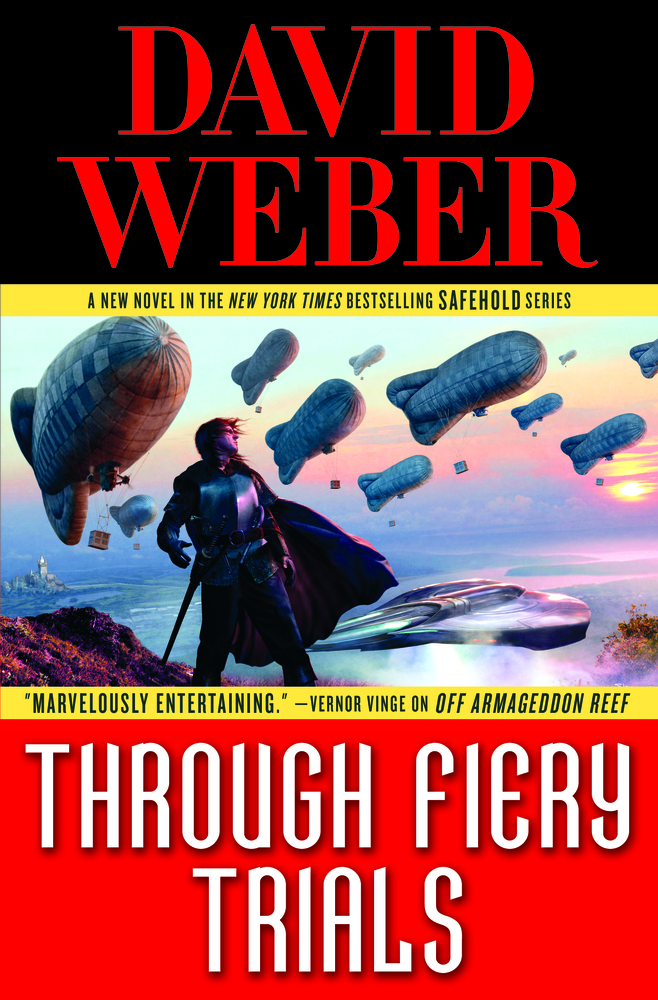

opens in a new window David Weber’s New York Times bestselling military science fiction series continues with opens in a new windowThrough Fiery Trials.

David Weber’s New York Times bestselling military science fiction series continues with opens in a new windowThrough Fiery Trials.

Those on the side of progressing humanity through advanced technology have finally triumphed over their oppressors. The unholy war between the small but mighty island realm of Charis and the radical, luddite Church of God’s Awaiting has come to an end.

However, even though a provisional veil of peace has fallen over human colonies, the quiet will not last. For Safefold is a broken world, and as international alliances shift and Charis charges on with its precarious mission of global industrialization, the shifting plates of the new world order are bound to clash.

Yet, an uncertain future isn’t the only danger Safehold faces. Long-thought buried secrets and prophetic promises come to light, proving time is a merciless warden who never forgets.

I: Nimue’s Cave, The Mountain of Light, Episcopate of St. Ehrnesteen, The Temple Lands

“No matter how many times Owl and I look at it, it keeps coming up the same,” Nahrmahn Baytz said. “Something’s obviously gone wrong with Langhorne and Chihiro’s master plan. We just don’t know what, and that’s what may kill us all in the end. Well, kill everyone else, I suppose, given your and my . . . ambiguous status.”

The hologram of the rotund little Emeraldian prince who’d been dead for almost five years sat on the other side of the enormous, round table. Nimue Alban (who’d been dead far longer than he had) had instructed Owl to manufacture that table—and make it round—even before she’d reconfigured her PICA into Merlin Athrawes for the very first time. Now Merlin sat tipped back in one of the reclining chairs with his boot heels parked inelegantly on the polished surface and waved a beer stein at the hologram.

“If it was easy, anyone could play and we wouldn’t need you,” he observed, and Nahrmahn chuckled a bit sourly.

“I don’t think most people would object if it wasn’t easy as long as they knew what the rules were!” he said.

“Nahrmahn, you spent your entire adult life playing the ‘Great Game.’ Now you’re going to complain about not having rules?”

“There’s a difference between creatively breaking the rules and not knowing what the damned things are in the first place!” Nahrmahn shot back. “The former is a case of polished and elegant strategies. The latter is a case of floundering around in the dark.”

“Point,” Merlin conceded.

He sipped from the stein in his right hand (a PICA had no need for alcohol, but he liked the flavor) and checked his internal chronometer. Fourteen minutes yet until the “inner circle” convened by com to discuss his and Nahrmahn’s recommendations. Finding a time when people in every time zone of the planet could coordinate com conversations without anyone noticing they were sitting in a corner talking to themselves was a nontrivial challenge, and usually only a relatively small percentage of the entire—and growing—inner circle could be “present.” More of them than usual would be making it tonight, however, and he wished the two of them had been able to come up with something more . . . proactive to share with them.

“I’m going to call it the ‘Nahrmahn Plan,’ you know,” he said now, smiling crookedly at the electronic ghost of his friend.

“Hey! Why do I get the blame?”

“Because you’re our designated Schemer-in-Chief. If there’s skulduggery afoot, your foot’s usually in it up to the knee, or at least the ankle. And because I believe in giving credit where it’s due.”

“And because you think the uncertainties built into its foundation comport poorly with your status as the all-knowing, ever-prepared Seijin Merlin?”

“Well, of course, if you’re going to be tacky about it.”

Nahrmahn chuckled again, but he also shook his head.

“I just wish there weren’t so many complete unknowns. Especially given what we do know. For example, we know the bombardment system’s still up there, we know its maintenance systems are still operable, we’ve proved there’s a two-way com link between it and something under the Temple, and we know its automated defenses took out the probes Owl sent towards it right after you woke up and started flailing around in your ignorance.”

“Hey!” Merlin protested with a pained expression.

“Well, you did!” Nahrmahn shook his head again. “If whatever’s missing in the command loop hadn’t been missing, how do you think it would’ve responded to the evidence of a competing source of high-tech goodies? You’re just damned lucky the system never even noticed, beyond swatting the pesky flies buzzing around its platforms!”

“All right,” Merlin conceded. “That’s fair.”

“Thank you.” Nahrmahn sniffed. “Now, as I was saying, we know all of that, but why in God’s name did Chihiro leave it set up that way? Operating so . . . half-arsed? Why isn’t it doing anything about all the steam engines and blast furnaces we’ve strewn across the planet? That’s got to be a flare-lit tipoff that technology is reemerging, so why no kinetic bombardments? Why don’t Charis and Emerald look like Armageddon Reef?”

“Because it’s looking for electricity?” Merlin suggested. “I’ve always thought it’s significant that the Book of Jwo-jeng specifically anathematizes electricity whereas the Proscriptions are defined in terms of what’s allowable. They don’t say ‘You can’t do A, B, or C;’ they say ‘You can’t do anything besides A or B.’ But not about electricity. And in addition to what she had to say about it, Chihiro says ‘You shall not profane nor lay impious hands upon the power the Lord your God bestowed upon his servant Langhorne.’” His lips curled in distaste as he quoted from the Book of Chihiro. “That’s why I’ve always assumed electricity would almost have to be a red line as far as any automated system under the Temple was concerned.”

“And I tend to agree with you. But don’t forget your own point—Chihiro anathematized it in terms of the ‘Rakurai’ Langhorne used to punish Shan-wei for her defiance of God’s law. Lightning’s sacred, unlike wind, water, or muscle power, so its use in any way is expressly forbidden.”

“But Chihiro goes on to specifically describe electricity, not just lightning,” Merlin pointed out. “People may call the damned things rakurai fish, but they don’t flash like rakurai bugs. They just shock the hell out of anything that threatens them! But Chihiro uses them as a ‘mortal avatar’ of Langhorne’s ‘Holy Rakurai’ placed on earth to remind humans of the awesome power entrusted to him by God. That’s why the Writ says rakurai fish are sacred in the eyes of God, but where’s the ‘lightning bolt’ in their case? He flat out tells people they have the same power as the Rakurai, and he didn’t have to. For that matter, the Writ even talks about static electricity and links that to Langhorne’s Rakurai, too.” It was his turn to shake his head. “There’s got to be a reason that Chihiro gassed on about it that long and that thoroughly, and the most likely one was to make damned sure no one even thought about fooling around with it.”

“I said I agree with you, and there’s no way in hell I want us playing around with electricity, because you may well be right. That could be the one-step-too-far that triggers some sort of auto response. I’m just saying any sort of threat analysis looking for the emergence of ‘dangerous’ technology should already have been triggered even withoutelectricity. And that I don’t understand why someone as paranoid as Langhorne—or, especially, Chihiro—didn’t set up that threat analysis.”

“Unless he did and the system’s just broken,” Merlin suggested.

“Which certainly seems to be what’s happening, yes.” Nahrmahn’s avatar stood and began pacing around the conference room, apparently oblivious to the fact that its feet were at least an inch above the floor. “The problem is that it seems to be the only part of the system that’s broken. I wish we could get a sensor array inside the Temple, but everything we can see from the outside—and all of the stories about the routine ‘miracles’ that go on inside it—seem to confirm that everything else is working just fine, even if no one has a clue how. So is the system really broken? And if it is, is there something we might do that could reset it? The last thing we want to do is turn it back on if it’s gotten itself switched off somehow!”

“Nahrmahn, we’ve been over this—what, a dozen times? Two dozen?” Merlin said patiently. “Of course there may be an ‘on button’ we don’t know a thing about. But whatever it might be, we obviously haven’t hit it yet. And you’re right, we’ve been scattering stuff all over Safehold for nine or ten years now. So it doesn’t look like sheer scale’s the critical factor. The threshold has to be something qualitative, not quantitative. Assuming there is a threshold, of course.”

“Oh?” Nahrmahn paused in his pacing, hands folded behind him, and raised an eyebrow at the far taller seijin. “Are you suggesting we might assume there isn’t one?”

“Of course not!” Merlin rolled his eyes. “I’m just saying it would appear we can go on doing what we’re currently doing without getting blown up for our pains. And there are a lot more innovations we can introduce without going beyond water, steam, hydraulics, and pneumatics.”

“I’ll agree that that’s most probably true,” Nahrmahn said after a moment. “Whether it is or not, we have to assume it is or sit around with our thumbs up our arses without getting a damned thing done, anyway, and the clock’s ticking.”

“Damn, I wish we could get into the Key,” Merlin sighed, and Nahrmahn snorted harshly in agreement.

The Key of Schueler was the most maddening clue they had—or didn’t have, actually—about Safehold’s future. According to the Wylsynn family tradition, the Key had been left by the Archangel Schueler as both the repository of his inspirational message to the family he’d established as the special guardians of Mother Church and as a weapon to be used by the Church in its time of greatest need. What it actually was was a memory module: a two-inch-diameter sphere of solid molecular circuitry which could have contained the contents of every book ever written on Safehold. What it actually did contain, aside from the recorded hologram of Androcles Schueler delivering his exhortation to the Church’s guardians, remained a mystery. Owl, the artificial intelligence who resided in the computers in Nimue’s Cave along with Nahrmahn’s electronic personality, had determined that at least one of the files tucked away inside it contained over twelve petabytes of data, but no one had a clue what was in it and the Key’s security protocols precluded accessing it without the password no one possessed.

It was entirely possible that the answer to every question facing them was contained inside the Key.

And they couldn’t get at it.

“That would be nice, for a lot of reasons,” Nahrmahn agreed. “Especially if the damned thing would tell us exactly what the hell Schueler meant by ‘a thousand years’!”

Merlin grunted, because Androcles Schueler’s promise to the Wylsynns that the “Archangels” would return “in a thousand years” was the true crux of their problem. If they weren’t coming back, the time pressure came off and the inner circle could take however long it needed to find the right solution. But if someone—or something—actually was coming back to check on the progress of Eric Langhorne’s grand scheme, whatever they or it might be would undoubtedly command the kinetic bombardment system, at a minimum.

That could be . . . bad.

Of course, there was no way of knowing if the Wylsynn family tradition that he’d promised anything of the sort was accurate. No one had been going to write something like that down, so it had been passed purely orally for almost nine centuries, and a few little details—like the password for the Key, for example, assuming the Wylsynns had ever known it—had gotten lost along the way. No one was certain if Schueler had meant that he and the other “archangels,” themselves would return—although that seemed unlikely, since most of them had been dead even before he recorded his message—or if something else would return. Or where whatever it was would return from, for that matter, although given all of those active power sources in the Temple, Merlin knew where he expected it to come from.

And had he meant the return of whoever or whatever was coming back would occur a thousand years after the Day of Creation when the first Adams and Eves had awakened here on Safehold? Or had he meant from the time he left the Key, at the end of the War Against the Fallen? Mother Church had begun counting years from her victory against the Fallen, but the war hadn’t ended until seventy-plus Safeholdian years after the Day of Creation. So, if Schueler had meant a thousand years after Creation, he’d been talking about sometime around the middle of July of 915. If he’d meant a thousand years from the time he left the Key with the Wylsynns’ distant ancestor, he’d been talking about the year 996 or so. Or he could simply have been talking about the year 1000, a thousand years after the start of the Church’s post-Jihad calendar.

So we have fifteen years . . . or ninety-six . . . or a hundred and ten, Merlin thought now. Nothing like a little ambiguity to liven up the day.

“You know Domynyk’s going to argue in favor of a fullbore onslaught on Church doctrine because we only have fifteen years,” he said out loud.

“And I imagine Ahlfryd will support him,” Nahrmahn agreed.

“And not just because he wants the Church kicked out on its ass.” Merlin chuckled. It was not a sound of unalloyed mirth. “Braiahn was right about Ahlfryd’s . . . impatience. Mind you, I still think Sharley was right and we needed to tell him, but he wants to tear down the Temple yesterday, if only so he can start playing openly with Federation tech!”

“I’m sure, but Maikel and Nynian—and, to be fair, you—are right. We can’t go straight for an attack on the Church this soon after the Jihad.” Nahrmahn’s expression darkened. “Too many millions are dead already, and what looks like starting up in North Harchong’s likely to be bad enough without cranking an overt religious war back into it. God knows, nobody in the North’s going to be a candidate for industrialization, so it’s not going to affect that side of things much, but the violence is going to be ugly as hell, and I’m pretty sure the divide between Zion and Shang-mi will already put religion front and center in it for a lot of those people. The Spears may be keeping the lid more or less screwed down so far, but when Waisu—or his ministers, anyway—decided the Mighty Host could never come home, they lit a fuse nobody’s going to be able to put out. Sooner or later, the spark’s reaching the Lywysite, and an awful lot of people will get killed when it does, if Owl and Nynian and Kynt and I are reading the tea leaves accurately.”

The hologram gazed broodingly at something only Nahrmahn could see. Then he shook himself.

“It’s going to be bad enough without our injecting religion back into the mess by attacking Church doctrine in the middle of it,” he repeated, and chuckled mirthlessly. “Besides, the one thing we absolutely can’t afford is to reopen that whole can of worms about demonic influence on Charisian innovation.”

“Which only leaves the nefarious, unscrupulous, underhanded ‘Nahrmahn Plan.’”

Merlin smiled as Nahrmahn perked back up visibly at his choice of adjectives, but then the little Emeraldian shook his head with a chiding expression.

“That’s really not fair,” he replied. “Especially since the original idea came from you.”

“I think it occurred pretty much simultaneously to several of us,” Merlin countered, “but I do like some of the . . . refinements you’ve incorporated. It’s nice to see a little thing like dying hasn’t diminished your devious quotient.”

“To quote Seijin Merlin, ‘One tries,’” Nahrmahn said, and bowed in gracious acknowledgment of the compliment.

Merlin chuckled again. Not that there was anything all that humorous about their options. Given ten years or so to openly deploy the capabilities of Owl’s manufacturing capacity here in Nimue’s Cave—and for it to clone itself and begin producing Federation-level technology outside the Cave—any belligerent “Archangels” who returned would find themselves promptly transformed into glowing clouds of gas, and their most pessimistic estimate gave them at least fifteen years before the return. The existence of the bombardment system, however, meant they couldn’t deploy their own industry without almost certainly triggering that “reset” Nahrmahn feared. So, since they couldn’t defeat any return by the archangels, the best they could hope for was to create a situation in which those archangels recognized the technology genie was irretrievably out of the bottle. If a native Safeholdian tech base could be spread broadly enough across the planet to make its eradication by bombardment impossible without killing enormous numbers of Safeholdians, any semi-sane “archangel” would settle for a soft landing that accepted the inevitable. If the returnees weren’t at least semi-sane, they might well opt to repeat the Armageddon Reef bombardment on a planetwide basis and damn the casualties, of course, but as Cayleb had put it with typical pithiness “If they’re that far gone, we’re screwed whatever we do. All we can do is hope they aren’t and plan accordingly.”

So, assuming the earlier return date, the inner circle had fifteen years to spread Charis-style industrialization as broadly as possible around the planet. From the purely selfish viewpoint of the Charisian Empire’s economic power, “giving away” its technological innovations would be a very poor business model. From the viewpoint of trying to keep everyone on the planet alive, however, it would make perfect sense, although that wasn’t something they’d be explaining to anyone.

Nothing could be allowed to interfere with that process, and that was the reason, more even than the staggering potential casualties of a renewed Jihad, why any headlong assault on the Church of God Awaiting’s fundamental doctrine had to be avoided . . . or at least postponed. Nahrmahn was right about what looked like firing up in Harchong, no matter what else happened, but he was also right about the need to keep any doctrinal conflict out of the equation. They couldn’t afford to reawaken the charge that all of these innovations were the handiwork of Shan-wei, spreading her evil among humankind. If 915 came and went without any angelic reappearance, they’d have another eighty-five years to work on doctrinal revolutions.

And in the long run, that’s as important as any piece of hardware, Merlin reflected. “Archangels” who turn up and discover that everyone’s laughing at them or giving them the finger instead of bowing down to worship them are a lot less likely to think they can cram the genie back into the bottle, and that has to be a good thing from our perspective. And I do like Nahrmahn’s notion about the opening round if we decide a time’s come when we can go after the inerrancy of the Writ.

“It’s going to dump a lot of responsibility on Ehdwyrd’s shoulders,” he said out loud, “and he’s going to have to come up with some fancy footwork to convince his board and his fellow investors to let him more or less give away their technology.”

“I’m sure he’ll be up to the task,” Nahrmahn said dryly. “And if he isn’t, there’s always Cayleb and Sharleyan. Or you could go stand behind him at the next board meeting and loom menacingly.”

“I do do a nice ‘ominous,’ if I say so myself,” Merlin conceded. “And Nynian’s been helping me work on a proper curled lip.”

“Has she really?” Nahrmahn looked the far taller seijin up and down. “I admire her willingness to tackle challenges. Especially when she’s working with such . . . unprepossessing material.”

Copyright © 2019

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Comments are closed.

Leave a Reply