opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

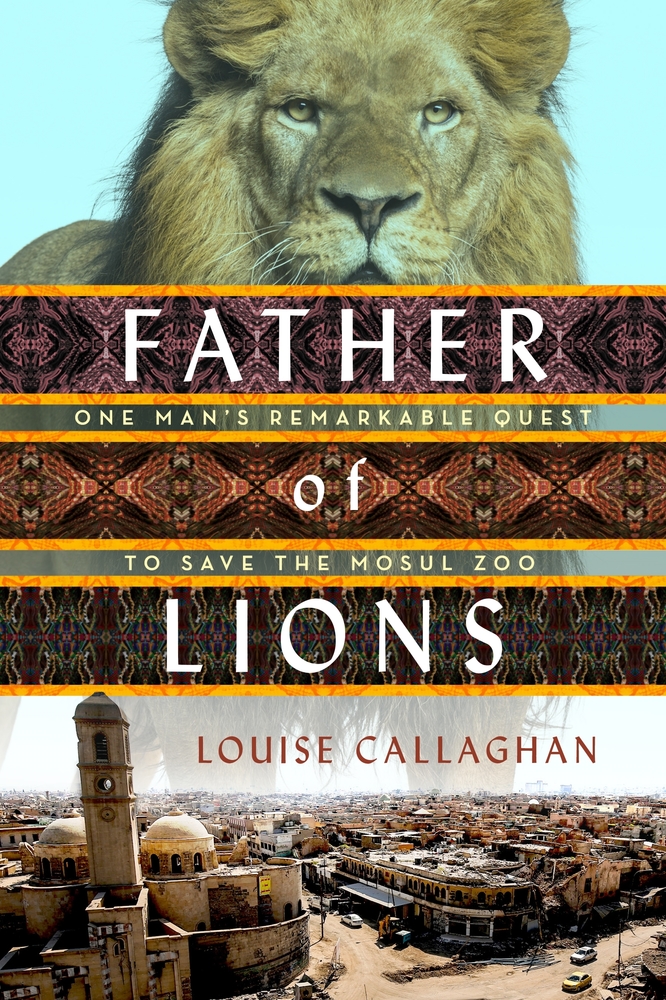

opens in a new window Father of Lions is the powerful true story of the evacuation of the Mosul Zoo, featuring Abu Laith the zookeeper, Simba the lion cub, Lula the bear, and countless others, faithfully depicted by acclaimed, award-winning journalist Louise Callaghan in her trade publishing debut.

Father of Lions is the powerful true story of the evacuation of the Mosul Zoo, featuring Abu Laith the zookeeper, Simba the lion cub, Lula the bear, and countless others, faithfully depicted by acclaimed, award-winning journalist Louise Callaghan in her trade publishing debut.

Combining a true-to-life narrative of humanity in the wake of war with the heartstring-tugging account of rescued animals, Father of Lions will appeal to audiences of bestsellers like The Zookeeper’s Wife and The Bookseller of Kabul as well as fans of true animal stories such as A Streetcat Named Bob, Marley and Me, and Finding Atticus.

opens in a new windowFather of Lions by Louis Callaghan will be available on January 14. Please enjoy the following excerpt!

Abu Laith

Abu Laith was not the kind of man to let another man insult his lion. Especially not a man who looked like this.

He was wearing a short-sleeved shirt, well pressed, and had the air of a civil servant. He carried a baby in the crook of his left arm. In his right hand he held a reed, plucked from the banks of the River Tigris, which he was using to poke Abu Laith’s newly acquired lion cub, who was asleep in his cage.

The man’s wife and the rest of his children stood nearby, watching sullenly. Despite his efforts, the poking was having no measurable effect on the lion, who wasn’t moving at all. All of this registered in Abu Laith’s mind as he ran at full pelt through the zoo towards the man, who had not seen him coming.

It was around 7.30 p.m. in the zoo by the Tigris, and the dusk was settling pink over Mosul’s Old City. Families were sitting outside the zoo cafe drinking cold Pepsi and glasses of tea. The bears were reclining in their cages as Abu Laith charged past.

‘What are you doing?’ shouted the self-appointed zookeeper, who rarely spoke at less than a bellow. ‘Get out of the zoo.’

The man, who did not realize the danger he was in, barely glanced up. ‘Why aren’t they doing anything?’ he asked, irate. ‘We paid money to see them.’

Abu Laith came to a dead halt in front of the family. ‘They’re full,’ he shouted. ‘They’ve just eaten. When animals are full, they sleep.’

The man, who wasn’t listening, kept poking at the lion cub. Next door, the lion’s mother and father—known to the zoo’s employees as Mother and Father—were also asleep.

‘We paid money to see them move,’ the man said, prodding the lion cub again.

‘How would you like it if I poked your children with a stick?’ Abu Laith spat, advancing on the family.

The man, who had finally got the message, backed away, his wide-eyed family backing with him. ‘I’m not coming here again,’ he said, snippily.

‘Good,’ called Abu Laith, as the visitors turned and scuttled off. ‘And you had better not, because if you do I’ll feed you to my lion.’

Grumbling to himself, Abu Laith turned his attentions to the cub. He was sound asleep, and looked not unlike a middle-sized ginger dog. None of the zoo workers, who were milling aimlessly around the park, had reacted to Abu Laith’s outburst. They were used to it.

Everyone always said that Abu Laith himself looked like a lion, and it was true. He was five foot six with a rock-hard keg of a belly and an opaque halo of orange hair. His nose looked like it had been hewn from a boulder and sprinkled with freckles. He spoke in a roar.

That was why they called him Abu Laith, which—loosely translated—meant Father of Lions.

Since he could remember, Abu Laith had loved animals, and devoted himself to them at the near-absolute expense of humans. He had raised dogs, pigeons, rabbits, cats and beetles and held them in his hands when they died. For his third-eldest daughter’s birthday, he had driven a herd of sheep into the family home. He had once given a baby monkey a shower in his garden.

He had one ultimate, lifelong ambition: to live on a farm with large predators roaming free around him. In Mosul, this was considered a suspect ambition. It had, possibly, something to do with the restrictions on animals in the Quran. In the holy book, dogs were listed as haram—unclean—along with pigs, donkeys, bandicoots, parrots, glow-worms (and all such bloodless animals), snakes and forest lizards (animals that have blood, but whose blood does not flow).

Most people, even if they weren’t religious, thought that dogs were dirty, and somehow unsavoury, in the way that people in Europe felt about rats: plague carriers and unclean beasts that defiled their surroundings. Though some families kept pets, it was considered disreputable to own a lot of animals. Among the people of the great city by the Tigris, animal lovers had a shady reputation as hustlers, fighters and panhandlers. Pigeon breeders, a fraternity to which Abu Laith also belonged, were especially dodgy.

Under the Iraqi legal system, pigeon owners were not considered trustworthy enough to testify in court. They had a reputation for always getting into fights and drinking too much whisky. Abu Laith fitted the stereotype all too well. He was a shaqawa—a kind of good-hearted neighbourhood thug. The sort of man you might call if you needed an extra pair of fists in a fight, or if someone was harassing your daughter, and needed to be scared off. He would never let anyone else pay for lunch, and always lent money to his relatives, grasping as he thought they were.

Since he was a young man, Abu Laith had made his living as a mechanic, fixing cars in the neighbourhood—at first for a few dinars here and there, but now he owned a big garage with several employees, where he charged hundreds of dollars to fix large American cars of the kind favoured by Mosul’s elite. But this was nothing more than a distraction from his real love: large, dangerous animals.

In 2013 he had decided to take an enormous step, which he hoped would change his life for the better. He was going to build his own zoo: a wide, open space with a park for animals to roam, and offices and apartment blocks that looked over it. It didn’t matter that the city was plagued with suicide attacks and kidnappings. In Abu

Laith’s mind, the development would be a lot like Dubai—slick skyscrapers and open lands on the bank of a mighty waterway, albeit the Tigris rather than the Persian Gulf.

As he gathered together his funds, wrenching money back from tight-fingered relatives and strong-arming investors, he had searched for a plot of land. He discovered that a large swathe of grass on the eastern bank of the Tigris was for sale. There was already a zoo next door. To Abu Laith, the plan seemed fated to succeed, as long as the two businesses could combine into one large zoo. Once he had finished building the new development, he could buy the animals from the existing zoo, adding new ones if he needed to.

One bright morning, he went and spoke to the owner of the zoo, a rich man from Mosul known as Ibrahim, who lived in Erbil, a Kurdish city 50 miles to the east. Like most wealthy people from Mosul, Ibrahim hid his money, knowing it would be a magnet for kidnappers and spongers. When he travelled around Mosul, he went in a simple taxi. He wore poor-quality clothes, rather than fine suits. Abu Laith understood this, and understood how he could be of service.

‘I know you can’t be here to keep an eye on your business,’ he told Ibrahim, when he went to see him. ‘But I know animals, and I know Mosul. If we work together, I’ll make sure your animals are looked after well. Then we’ll expand it together, and we’ll make some money.’

As it was, Abu Laith knew very well, the animals at Ibrahim’s zoo were in a pitiful state. He had been to scout it out a few times, and had been appalled at what he saw. The bears—a Syrian brown bear called Lula and her mate, who wasn’t called anything at all—were tetchy and worried by the fireworks that were set off to entertain visitors nearly every Friday evening near the zoo. The ponies were skinny, and the lions in their metal cages, about the size of a car, were bored and left roasting in the sun.

Abu Laith decided to step in and transform the lacklustre park into a proper zoo. With Ibrahim’s blessing, he began to visit the animals after he finished at the repair shop. Abu Laith, despite never having been a zookeeper before, had spent his life preparing for the role. From hours of watching the National Geographic channel, a years-long obsession of his—it played uninterrupted in his Mosul home—and from owning dozens of pets, he had accrued zoological knowledge that he considered unparalleled. When he was unleashed on Ibrahim’s zoo, it was as if a bomb had fallen from the sky. The zoo employees quickly learned to shuffle off when they saw the portly red-headed man stalking towards them. He would inevitably be getting ready to shout at them for not having cleaned the cages, or for feeding barley to the lions.

‘They need meat,’ he would spit. ‘Fresh meat, only just dead.’

Abu Laith was in his element. Soon, he hoped, he would have raised enough funds to start building his own park on the plot of land he had bought next door to the zoo, which for the moment lay empty. When it was done, these animals would be able to run free, rather than being cooped up in those small, hot cages.

It would begin with the lion. By early 2014, Abu Laith had for six months been the proud owner of a lion cub. He had tawny orange fur, and a notch on his upper lip where he had caught it on some chicken wire that Abu Laith had ill-advisedly used to protect the his cage from stick-wielders and other disturbers of the peace.

The lion cub was his first acquisition for the new zoo—the first animal that would be truly his, and not Ibrahim’s. He had first met the cub in Ahmed’s house, which lay about half an hour east of the Old City. Ahmed worked at the zoo, and he infuriated Abu Laith, who disliked the way he always wore tracksuits and his disdain for the proper feeding habits of animals.

For some time, Abu Laith had expected that Ahmed might be hiding something from him regarding the pregnancy of a lioness who had been brought to the zoo two years before with her mate. Abu Laith suspected that when the lioness gave birth, Ahmed would try to steal her offspring and sell the cubs without the knowledge of the zoo’s owner.

While he might often turn a blind eye to some stealing, Abu Laith was not going to be cheated out of a lion. As a self-styled manager of Ibrahim’s zoo, he had decided early on that he had a claim on the lion cubs, and had arranged to buy as many of them as he could once the lioness gave birth.

Though he had never seen them in the wild, Abu Laith knew a lot about lions courtesy of National Geographic. He knew, for example, that lions sharpened their claws on stones, and that they liked to sleep after dinner.

All Ahmed knew about, he thought, was money. So when one day the pregnant lion started looking a bit skinnier again, with no sign of the cubs, Abu Laith suspected immediately that something was up. Biding his time, he waited on the street outside his house until Ahmed’s eldest son walked past.

‘Son,’ Abu Laith called nonchalantly. ‘Do you know where your father is keeping the lion cubs?’

‘They’re at home,’ said the boy.

It wasn’t long before Abu Laith was parking his large American car outside Ahmed’s house, a small building with a garage. Inside the garage sat Ahmed, who was peering into a modest brick structure containing two very small lions, each no bigger than a loaf of bread.

Abu Laith was furious. ‘Why did you separate them from their mother?’ he shouted, as he stormed into the room. ‘Now if she sees them, she’ll smell human on their fur, and she’ll eat them.’

Ahmed, lounging in his tracksuit, didn’t seem to care. ‘Which one do you want, then?’ he asked, clearly exasperated that he’d been rumbled.

Abu Laith crouched down and cast a professional eye over the lions. Moving slowly, so he wouldn’t scare them, he opened the door to their enclosure. Immediately, one of the cubs jumped out and on to a white plastic chair that stood in the middle of the garage.

‘This one is mine,’ he declared, beaming at the young lion, who looked back at him calmly. Within a matter of days, Abu Laith had installed the lion in a cage next door to his parents in Ibrahim’s zoo.

After a period of consideration, he decided to name the cub after the lion in a cartoon about African animals that he had watched with his children, complete with mistranslated Arabic subtitles: he would call him Zombie.

Immediately, he set to work training the lion. He taught Zombie to sit quietly outside the cage when it was being cleaned. When he told him to go back into the cage, Zombie would obey. The cub knew not to bother the other animals in the zoo. Across the way from Zombie lived the two brown bears, Lula and her mate. The male bear was admirably strong, Abu Laith thought, and very protective of Lula. When the zookeepers had once tried to move him into a separate cage from his female companion, he had roared and fought so much they had given up.

Lula was a quiet soul who liked honey. When Abu Laith finished up at his mechanic’s shop, he would come to the zoo with half a kilo of honey for Lula, who would eat it and lick it from her paws. She liked apples, but only if they hadn’t touched the ground. She was a very clean bear.

The training continued apace, and within a few months Abu Laith knew, with the confidence of a man who had only met four lions in his life, that he would be able to tell Zombie apart from a thousand others of his species.

When night fell, and all the families and the small, annoying children were gone, Abu Laith would take a bottle of whisky to the zoo and sit down with Zombie for a yarn.

‘If animals are really dirty,’ he would sometimes ask, gazing out over the Tigris as the reeds rustled, ‘why did God create them?’

The lion couldn’t answer, but Abu Laith thought he knew what he was talking about.

A few months after Zombie came to the zoo, however, Abu Laith’s dreams of building his own wildlife park on the Tigris were dashed by a suicide attack that killed one of his business partners in the zoo-building venture just as he was emerging from Abu Laith’s front gate. He had been drinking with the man in his courtyard, and Abu Laith survived, but was accused by the police of having ordered his partner’s murder.

Because the man had died in front of his house, Abu Laith felt compelled to pay compensation to his family to the tune of almost all his considerable fortune, amassed through years of saving up every dollar from fixing American cars. After four months in prison, when he was released after the police realized he wasn’t a murderer, he came to the zoo to see Zombie, his dreams of re-creating Dubai on the Tigris in tatters.

He could feel the lion had missed him.

Copyright © 2020 by Louise Callaghan

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window