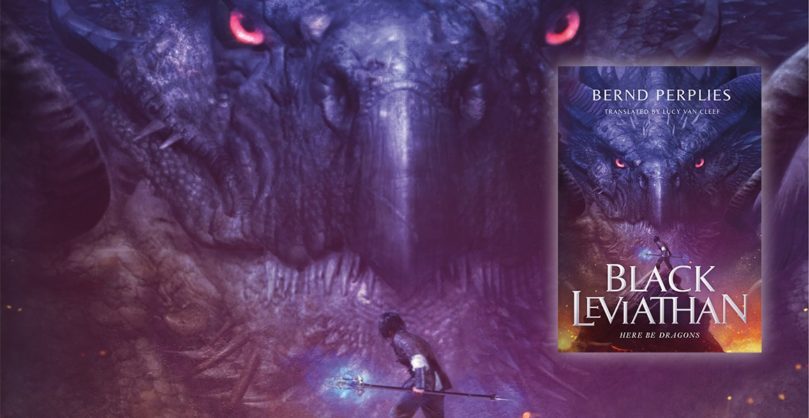

German author Bernd Perplies and American translator Lucy Van Cleef swap questions about Black Leviathan, the translation process, and the possibilities within the worlds of fantasy for exploring the bigger picture.

German author Bernd Perplies and American translator Lucy Van Cleef swap questions about Black Leviathan, the translation process, and the possibilities within the worlds of fantasy for exploring the bigger picture.

Bernd: Black Leviathan was your debut novel translation. What was the experience like? Were there any specific challenges?

Lucy: I come from a world outside of fantasy fiction. I used to be a professional ballet dancer, and now I work primarily as an arts writer. Believe it or not, the worlds of fantasy and arts writing are surprisingly similar. In both, you have to find the right words to describe the intangible – things that don’t exist in the real world. Your writing had the immediacy and color of a live performance: the Sidhari facing the bad guys; Lian and Canzo at the Taijirin wedding; falling to the Cloudmere floor – those were the fun parts for me!

I live in Berlin and speak German in most of my daily life, but I write in English: my own fiction, arts writing, and translations. This project was a chance to blend all of these factors. It was a challenge because of the sheer size of the project, but it was also huge learning experience. Sometimes you can say something in English with far fewer words than you need to express the same thought in German. It can be a hunt for the right words. This translation took a lot of time, and it was a struggle to stay consistent throughout the process. You get better as you go, and wish you had the tools you gained from the start. But that’s the way it goes. I hope I’ll get to do more in the future.

Lucy: In addition to your own fiction writing, you’ve also translated books from English to German. Have your Star Trek translations influenced your fiction at all? Is there any concrete crossover? Or any general inspiration for your fictional world in Black Leviathan?

Bernd: I’ve been a Star Trek fan for many years. The series appeals to me because of its optimistic vision for the future, how the stories inspire the audience to think, and the camaraderie among members of the Enterprise’s crew – and subsequent starships. The Star Trek television series ended in 2005 (not counting recent shows like Star Trek Discovery). Since then, the novels have kept the franchise alive for me; working on the translations for Cross Cult kept me from losing sight of Star Trek. And there are certainly aspects of that work that have affected my own writing.

For example, I love to tell stories about bands of characters on journeys together. I’m most interested in characters’ interactions with one another. In Black Leviathan, the crew of the drachenjäger ship, Carryola. Just like Star Trek authors, I strive to question the state of things, and to make readers consider similar aspects in the real world. In classic fantasy, dragons tend to be the monsters, and dragon slayers the heroes. Black Leviathan draws a more ambivalent picture. Aren’t the slayers another form of monster? And aren’t dragons, in all their destructiveness, also victims? I even have a certain empathy for both Adaron and Gargantuan. Both are extreme characters – but one strikes because he’s devoured by sorrow, while the other strikes to protect his kind.

There’s no real cross-over. But still, Star Trek and Black Leviathan do have something in common; both criticize, more or less, real-life whale hunting. The movie Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home tells the story of Captain Kirk returning to the year 1986 to find humpback whales, which had gone extinct in the future, year 2286, and are the only salvation for preventing humanity’s destruction by an extraterrestrial probe. Black Leviathan, alternately, poses the question of whether hunting majestic creatures of the ocean (the Cloudmere) is justified – and if so, to what extent?

Bernd: German has more than one form of the pronoun “you”: “Du” (familiar or derogatory), “Sie” (formal or distanced), “Ihr” (pseudo old-English). English doesn’t have these cases. In Black Leviathan, it’s common for residents in a particular region of the Cloudmere to address each other with “Ihr,” (even in the derogatory). There’s only one exception: when speaking to a family member or loved one. In one scene of the novel, a man and woman switch mid-conversation from “Ihr” to “Du,” saying something “between the lines” in the process. How did you navigate that in your translation?

Lucy: Yes, this was a tricky one. In English, there’s only one word for “you.” But there are still ways to adjust the formality of an exchange. You wouldn’t address a business associate the same way you would address family. So I tried to find the appropriate solutions for the context. One example: Ialrist always addresses Adaron by his first name, whereas all other crew members call him “Captain.” Their friendly relationship is established in the first two chapters, and carries over throughout.

I was very lucky to not be alone during this process; Tor supported me from start to finish, and their amazing editor helped me find the right solutions along the way. Since there’s no one word to show the shift in tone between the man and woman in the scene you mentioned, we altered that exchange slightly for the American market. I hope the solution honors the original text and makes sense to readers.

Lucy: What about your experience translating from English to German? Have there been any cases where the solution wasn’t one to one?

Bernd: That always comes up. Puns are always tricky, naturally. Some authors use them more than others. They come up a lot in Star Trek, because many starship crews include both men and women who use a loose conversational tone to convey multiple meanings in their exchanges. Sometimes the wordplay happens to work on its own, but usually you’ve got to find a solution that makes some sort of sense in German. You might be stuck with a witty saying that doesn’t match the English word for word.

Texts that rhyme are also especially hard. That kind of thing doesn’t come up much in Star Trek, luckily. But a long time ago, at the very beginning of my career, I translated a “magic book“ that gave spells for day-to-day life. It was a fun book for girls – nothing too serious. But during those weeks, I had to become really creative in order to come up with spells that rhymed in German and still had the same meaning they did in English.

Lucy: I have some experience with that too. I was so grateful that the visions Lian experienced toward the end of Black Leviathan weren’t in metered verse with rhymed endings.

Bernd: Both the publisher and you decided to maintain some of the original German wording, such as “Drachenjäger.” Why? Is that common practice in translations of foreign texts for the American market?

Lucy: We considered using the original title, “Drachenjäger,” for the English version. It’s a cool sounding word; “drachen” is close enough to “dragon” to be understood, and many English speakers are familiar with the world “jäger.” Even though we ultimately went with a different title, we stuck with “drachen” when referring to the lore of the world, and used “drachenjägers” as a title for the few souls brave enough to fight dragons. Then we developed an extended glossary to explain these words to readers. That’s how we were able to keep some German flavor in the fictional world of the Cloudmere.

Lucy: Who do you identify with more, Lian or Adaron?

Bernd: Definitely Lian! I sympathize with Adaron. He lost almost all of his friends, and the woman he loved, which led him down a dark road that he never really returned from. A shadow fell across his soul. Only his friendship with Ialrist, his only surviving friend, keeps him halfway sane. I can’t imagine ever becoming so vengeful, or so bitter.

Lian, on the other hand, is a dreamer. He’s pretty naiive in the beginning; he sees dragon hunting, and his journey into the Cloudmere, as a great big adventure. I definitely had a similar “romantic” side during my youth. Lian’s experiences aboard the Carryola make him grow. He becomes more critical, and questions his actions. Ultimately, he takes a stand for what he believes in, instead of continuing to do what (most) others on board are doing. We’re similar in that way, too.

Bernd: It’s pretty typical in Germany for publishers to translate foreign fiction, especially works from the American market. Is that true in the US as well? Are translations common there?

Lucy: I’m not an expert on the publishing market, but I’m a passionate reader. Good translations allow people from one country or culture to be exposed to another without having to learn a new language, or even leave their living rooms. I grew up in America reading books by both English-speaking and international writers. I’d say that translations are common, and necessary. I think it’s really important to learn from people with different frames of reference than our own. For that reason, I hope that the American market never stops publishing works by foreign writers.

Lucy: What’s next for your journey into the Cloudmere? Any fun projects planned?

Bernd: I can’t really talk about upcoming projects (in Germany), because they’re all in progress, and not official yet. I can, though, give an overview about what’s happened since 2017 – the year Der Drachenjäger (Black Leviathan) was published in Germany.

First, I took another journey into the Cloudmere. Der Weltenfinder (the world finder) tells the story of scholar and adventurer Corren von Dask, who aims to fall to the Cloudmere floor in order to explore the mythical city ThaunasRa, supposedly the origin of the Cloudmere. The plot is stand-alone, but is based on events and characters of the previous novel.

I ventured into outer space with Frontiersmen – Civil War, a six-part mini series. It tells the story of John Donovan, freighter captain and scoundrel, who along with his motley crew and a run-down cargo ship, is unvoluntarily drawn into a civil war between the bordering planets and the central world of his home galaxy. Frontiersmen is my version of a space-westerner, like the series “Firefly” or the Tatooine sequences in Star Wars, where the earth-based westerner meets the technology of the future.

My most recent work, which was released in October, is called Am Abgrund der Unendlichkeit (at the precipice of eternity), and is another science fiction novel. A mysterious darkness engulfs entire solar systems belonging to the galactic league of nations, the Domenaion. When chaos breaks out, the brave crew of a rescue cruiser searches for a solution to prevent billions from meeting their deaths.

I’m sorry to say that none of these works have been translated to English, yet. But I’d like to invite anyone with solid German skills to explore my fantasy worlds beyond Black Leviathan.

Order Your Copy of Black Leviathan now:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Err, sorry to correct you, but why do you think “Ihr” is pseudo-old-english? It is true that sometimes people get confused with the old-fashioned “thou” and “ihr” (cause both are, well, old fashioned). However, “Ihr” was a formal form of address in German, and is by no means “pseudo Old English”

I did not write “pseudo Old English”. I wrote “pseudo medieval”. (Have a look at the German version of the text on tor-online.de.) And I meant that today “Ihr” is mostly used in fantasy novels in context with a kind of pseudo medieval language. (I don’t say that in a derogatory way. I use this kind of language myself, because I think it fits the setting. It’s just not a real reflection of speaking in medieval times – well, as far as I know. 🙂 ) But you are right: “old-fashioned” would have been the better description.