opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

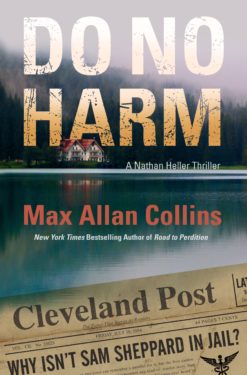

opens in a new windowDo No Harm is the latest mystery in the Nathan Heller series by New York Times bestselling author Max Allan Collins.

It’s 1954 and Heller takes on the Sam Sheppard case—a young doctor is startled from sleep and discovers his wife brutally murdered. He claims that a mysterious intruder killed his wife. But all the evidence points to a disturbed husband who has grown tired of married life and yearned to be free at all costs. Sheppard is swiftly convicted and sent to rot in prison.

Just how firm was the evidence…and was it tampered with to fit a convenient narrative to settle scores and push political agendas? Nathan’s old friend Elliot Ness calls in a favor and as Nathan digs into the case he becomes convinced of Sheppard’s innocence. But Nate can’t prove it and has to let the case drop.

The road to justice is sometimes a long one. Heller’s given another chance years later and this time he’s determined to free the man…even if it brings his own death a bit closer.

opens in a new windowDo No Harm will be available on March 10, 2020. Please enjoy the following excerpt.

Richard Kimble has been tried and convicted for the murder of his wife. But laws are made by men, carried out by men, and men are imperfect.

Roy Huggins, The Fugitive TV series

Our justice system is human and therefore it is apt to err.

Erle Stanley Gardner

Although this case was about a 1954 murder, those involved were real people with real hopes, dreams, and emotions…

Jack P. DeSario and William D. Mason

Be careful, then, and be gentle about death

For it is hard to die. It is difficult to go through

the door, even when it opens.

D. H. Lawrence

Chapter 1

Like a police car’s siren, the shriek penetrated his slumber.

Startled from a deep sleep, but still groggy with it, Dr. Sam Sheppard pushed up on his elbows as the siren became a scream, a woman’s scream, Marilyn’s scream, from their bedroom above.

Then: “Sam! Sam!”

He clambered from the daybed, positioned against the stairway wall, and started quickly up. The last he knew, he and his wife had been entertaining another couple, good enough friends to understand that after twelve tough hours at the hospital, he might crap out on the couch like this, no harm done. So the house was dark, company had gone home, with Marilyn off to bed.

Nothing unusual about any of it.

Even the cries from above, however concerning, did not alarm him. Marilyn, four months pregnant, might have been having convulsions, as when she carried their son Chip. The boy right now was in the bedroom beyond theirs, a sound sleeper like his dad.

These thoughts flashed through his mind in a few seconds.

But as the screams continued, and his thoughts came into focus, he knew something much worse than convulsions was wrong. He took the several steps to the landing, then at the top of the stairs, which rose vertically to meet the horizontal hallway, he found the door to their bedroom open. The screaming had stopped now, replaced by a raspy gurgling, and a figure in the darkness—a night-light from behind Sam providing scant illumination—was hovering over Marilyn, who was on her back. The figure was flailing, but then moved across his vision, in a blur of almost glowing white.

A T-shirt?

Sam rushed inside the bedroom to help his wife, who was moaning now, but first there was an intruder to deal with. He grabbed at the formless figure with its white torso, grappled with it in a fashion Sam hadn’t experienced since high school wrestling days. The grunting of their struggle joined the bubbling groans from the bed, when something struck him from behind.

Struck him hard.

The world went red, then black, as Sam fell to the floor.

When he awoke, he had no idea how long he’d been unconscious—a minute? An hour?

Feeling punch-drunk, he was on his stomach at the foot of the bed, his feet out the door and in the hallway. His dazed condition eased while the throbbing pain at the back of his neck—had that been a judo chop?—did not, and he pushed himself up, noticing his open wallet flung nearby, his badge (he was the local police physician) catching the dim light and winking at him. Absentmindedly, he stuffed the wallet in his pocket and he got shakily to his feet.

Even in the near darkness, he could see Marilyn, on her back, in her diamond-pattern pajamas, almost floating in blood, a damp veil of it covering her face, its coppery smell all pervasive. He checked her neck for a pulse that wasn’t there. Just enough illumination came from the night-light across the hall to reveal the unsettling shimmer of blood splashed on the walls.

He backed away from the horror and hurried to the room next door, Chip’s room, finding him deep asleep. Before he could even feel a sense of relief that his son had been spared, from violence, from the screams of his mother, the boy slumbering and blessedly unaware of their loss, Sam heard movement downstairs.

Lithely muscular, a thirty-year-old six-footer, Sam—in the T-shirt, slacks and moccasin-style slippers he’d sacked out in—ran down the stairs. In the darkness but silhouetted against the windows onto the lake, no glow of white now, was a nonetheless discernible form, a dark human form that must have heard him coming, because it, he, moved quickly across the living room and to and through the door onto the screened-in porch, facing the lake.

Sam followed the dark figure outside, through the screen door and across the narrow backyard, then down the thirty-six steps to the bathhouse on its platform eight feet above the lakeshore. As before, this was just a silhouette, but a silhouette of what appeared to be a man, a big man with a good-sized head and bushy hair.

Rattling down the remaining few steps, Sam caught up with him, and tackled him to the sand. Waves were hitting the shore as violently as the struggle on the strip of foamy beach rolling in nearby. Again, Sam found himself wrestling with an attacker, but when strong fingers gripped his throat and squeezed and squeezed, unconsciousness took him a second time.

When he awoke, he was belly-down on the beach, his feet and legs in the water, where the waves kept churning. His head was on the bank, out of the water, or he might have drowned.

Staggering to his feet, he came slowly to his senses. Was this a nightmare or reality? The cascade of surreal events could only make him wonder. He made his wobbly way up the many steps to return to the scene of horror on the second floor of the house looming above.

At the very least, Marilyn had surely been badly injured by the intruder—intruders?—and the husband, the doctor, went to his wife quickly, through the house, up the stairs. Again he found the scent of copper and the splash of blood and a woman with no pulse.

In a daze, he began to pace aimlessly, first upstairs, then down, and up again, and every time he re-entered the bedroom he hoped he would wake from this bizarre bad dream. But one final examination confirmed Marilyn was gone.

There would be no waking from this, for either of them.

He wandered downstairs, disoriented, sleepwalking through the kitchen, through his study and living room and finally he became focused enough to find the phone and call for help.

But what good had crying for help done his wife?

“What,” Erle Stanley Gardner asked me, “do you think of his story?”

The story, of course, belonged to Dr. Sam Sheppard of Bay Village, Ohio, whose wife Marilyn had been murdered in the early-morning hours of July 4, 1954. Dr. Sam, as many called him (including the Cleveland media who’d crucified him), was found guilty of her murder on December 21 of that year. He was currently in a maximum-security prison in Columbus.

“It stinks,” I said.

I had followed the case, which had made the Chicago papers—it got a lot of national coverage—and the accused husband’s account had been repeated again and again.

“I mean, your melodramatic touches improve it,” I granted, “but it’s still about as believable as a flying saucer sighting. I mean, who the hell gets knocked out twice in one fight?”

We were seated in Gardner’s knotty-pine office in the sprawling main house of his thousand-acre ranch outside tiny Temecula, California. The creator of Perry Mason and so many big-city mysteries was a would-be Westerner, with a tanned, weather-beaten oval face and snap-button open-collar tan shirt with black trim as evidence. He was one of those men of average height who seemed taller because of wide shoulders and a stout build, his brown hair going gray but the dark eyes retaining a boyish twinkle behind round-lens glasses with dark plastic frames.

“That’s what the jury thought,” Gardner said, between puffs of his pipe. “But much as I prize our system of justice, sometimes juries do get it wrong.”

“Sometimes it’s given to juries wrong,” I said.

I was not a Westerner, and my suit was strictly big city, a dark brown Botany 500 with a brown-and-yellow silk tie. I’d been more casually dressed when I’d driven the near two hours plus down from Los Angeles.

I’d never been to the writer’s Rancho del Paisano before, described to me as halfway between L.A. and San Diego, and got a little lost. Back roads, stretches of desert and grassy rolling hills brought me to a modest mountain where, about halfway up, the scattered buildings of the ranch awaited, almost hiding in a grove of oak trees.

My host had given me a quick tour of the eight guesthouses and the main building before depositing me at my own quarters, which were outfitted with a liquor cart, assorted Gardner novels, a thermos bucket of ice, and an electric heater for the morning cold.

I gussied up for dinner, which Gardner did not, and found myself seated at a long, narrow, well-polished slab of wood that passed for a table. Gardner had a small army of young women (younger than he was anyway) who were live-in secretaries. At least one of them had other duties—Jean, who cooked the meal (steak with salad and baked potatoes, simple but delicious) and joined us.

I didn’t read mystery novels, but I knew Della Street from TV and Jean might have been her.

This trip to California had been chiefly to see Gardner—specifically, to deliver three reels of tape recordings and other materials from a polygraph examination of Sam Sheppard’s two brothers and their wives that I had supervised at the John E. Reid and Associates lab back in Chicago.

I was not myself a polygraph examiner, but I’d had a longtime relationship with one of the machine’s inventors, the late Leonarde Keeler. Gardner and Keeler had both been part of the Harry Oakes investigation in Nassau, a decade or so ago. That was one of the famous cases that put my business, the A-1 Detective Agency, on the map.

And frankly I was fairly famous myself by now, with articles in Life and Look, as well as the true detective magazines, for whom I sometimes wrote up my cases. Well, we in the trade call them “jobs,” but the public who bought Gardner’s mysteries—The Case of the This, and The Case of the That—had long ago made their choice.

That minor-celebrity fame, and a friendship born in Nassau, where Gardner had been covering the Oakes murder for Hearst, got me roped into being an investigator for the so-called Court of Last Resort. Pro bono work, but the publicity was good. More newspaper and magazine articles for Nate Heller meant more business for the A-1, which now had Los Angeles and New York branches; home base was in the Monadnock Building in the South Loop.

I didn’t share this ulterior motive with Gardner, who was a millionaire book writer and could afford to be philanthropic. He kept on filling the paperback racks with his novels, plus had the Mason TV show going with Raymond Burr, who got courtroom confessions on a weekly basis. I bet Gardner’s weekly take was even more impressive. A Court of Last Resort series was coming soon, too.

Most people understood the premise of the Court—a bunch of experts—ex-cops, criminologists, lawyers, private detectives—looked into credible claims from men behind bars who felt they’d been wrongfully convicted. But the Court wasn’t some bustling legal office where, in some posh suite, specialists in crime-solving gathered in conference before polishing their magnifying glasses and scattering to balance the scales of justice.

No.

It was basically a monthly column by Gardner in Argosy, a men’s magazine of the guns and cars variety. Me, I preferred Playboy, but that I kept to myself also. The editor/publisher of the magazine, a longtime pal of Gardner’s, funded the expenses for the public defender–type work of the experts and investigators who did the author’s bidding by phone and telegram.

And, like I said, I was one of them. In a way I didn’t mind, because it got me back out into the field. The A-1 had grown so big lately that I really was the “President” I’d claimed to be in 1932 on the door of my one-room office on the fourth floor at Van Buren and Plymouth over a speakeasy. I’d been the only employee and slept there, too, on a Murphy bed. Now I was mostly supervising and doing PR, sleeping in a double bed in my modern townhouse, thank you very much, not always alone.

The trouble with the Good Old Days is you don’t know when you’re in them.

If you’ve done the math, you should know that the storied private detective seated opposite Erle Stanley Gardner was not a kid. I was in fact a well-preserved fifty or so, some gray at the temples of my reddish brown hair, six feet and two hundred pounds and handsome enough to play myself in the movies, though that had never come up.

And they were going to fictionalize me on the Court of Last Resort TV show. Meaning any money I got for it would be fictional, too.

“So what did you think of the Sheppards?” Gardner asked, as he rocked slightly in his swivel chair, periodically puffing at his pipe.

The desk was a massive mahogany thing edged with cowboy knickknacks, an anomaly in the knotty-pine space with its Indian rugs on the floor and Western paraphernalia on the walls—knives and spears and guns and ropes and framed pulp magazine paintings. Countless reference books crowded built-in shelves and a Dictaphone machine hugged the desk like a frightened time traveler.

I was lounging in an overstuffed leather chair I’d pulled around, an ankle on a knee.

“The middle brother seems to be in charge,” I said. “Both brothers are articulate, though Steve—brother number two—is more intense. Richard is there for the family, cool, quiet, a cheroot smoker. Steve is there for his brother Sam.”

“Some say they’re aloof,” Gardner said.

“I can see that. To me, I’d call it guarded. Your experts—Hanscom, Snyder, Gregory, Reid himself—say the whole damn clan passed with flying colors. Wives and all.”

Perhaps I should mention the small menagerie in attendance, a sort of ad hoc jury, milling about (when they weren’t lounging on sofas and comfy chairs like mine), were various dogs, of the stray variety, looking like Rin Tin Tin’s illegitimate offsprings; also a chipmunk, who could roam the desk at will, where right now were piled the tapes and original graphs of the polygraph exams, plus a list of the questions asked and answered.

“The chance that all four Sheppards could deceive experts like this,” Gardner said, absently scratching the chipmunk’s neck, “is about one in a million.”

I shrugged. “If that. But people have done it.”

With the pipe in hand, he waved that off, making a trail of smoke. “Not with experts like these. And not with a psychological hotshot like yourself looking on.”

I sipped a rum and Coke I’d been provided by Jean, who had since disappeared. “I appreciate that vote of confidence. But that doesn’t make a polygraph test admissible in court.”

“In the Court of Last Resort, it does,” he said, with a confident squint. He was a lawyer himself, and back in his criminal defense days, that must have been the look he trained on witnesses he was out to spook.

I grinned. “The court of Gardner, you mean.”

“The court of public opinion! My cynical friend, the polygraph is a scientific instrument. Does its job like a camera does its. A piss-poor photographer will give you a lousy picture. A top-notch polygraph operator will give you a real picture … and we used the best four in the country.”

A little dog hopped into my lap. When I got over being startled, I said, “What the hell kind of canine is this? Or is it a fox?”

“It’s not a dog, or a fox. It’s a coyote. A runty little one. But you can pet him like a dog. Name is Bravo.”

I petted it and the damn thing purred or something.

Gardner was right, of course, about the polygraph (I was careful never to refer to it as a “lie detector” in his crusty presence). The graph the machine made showed respiratory variations, as well as blood pressure, pulse, and skin resistance.

“You can’t beat the polygraph,” Gardner said, relighting his pipe with a kitchen match. “Unless you’re a psychopath. But you can beat the operator. Only, not these four.”

“Agreed.” I flipped a hand. “But what have you proven? Nobody ever suspected any of those Sheppards of murder.”

He sat forward and pointed the tip of his pipe at me like it was a .38. “No, but they’ve been suspected of covering up for Dr. Sam. To have helped him conceal evidence … or remove it. To have exaggerated his injuries so he could be whisked away to the nearby family hospital and dope him up so he couldn’t be properly interrogated.”

I nodded toward the pile of tapes and graphs and such on his desk. The chipmunk, finding them of no particular interest, jumped down and scampered off somewhere.

“All that stuff says they didn’t do anything of the kind,” I said. “Also shows that all four, wives included, believe in Sam Sheppard’s innocence. How about you, Erle? Do you think he’s innocent?”

Gardener thought about that. Bravo the miniature coyote on my lap watched its master as if in anticipation of his response.

“I think he deserves a better hearing,” Gardner said finally, “than he got. Now, I’m not saying he didn’t have a fair trial. That the jury didn’t do their best to be careful and impartial, despite all the publicity. His lawyer hasn’t been able to get the verdict set aside, you know.”

That was how the case had become the baby of the Court of Last Resort—all other options seemed closed to Sam Sheppard.

“General opinion,” I said, “was that he did it.”

“At the time,” Gardner said with a nod. “But a steady stream of letters from those who feel otherwise have poured in to Argosy and editor Harry Steeger, and directly to me, as well. A sizeable public out there feels the widespread publicity did adversely affect the outcome.”

“People also voted for Adlai Stevenson. That doesn’t make him president.”

“And others,” he said, ignoring that, “including a good number of attorneys, feel the evidence—almost entirely circumstantial, by the way—was not sufficient to prove Dr. Sam guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. And that’s the standard required in our courts.”

“Fine,” I said, after a sigh and another sip of rum and Coke, “but now it’s in your lap. If you have any questions about what’s on those tapes, or the other material, I’ll be in L.A. for the rest of the month. You can catch me at the Beverly Hills Hotel.”

The squint was gone but the friendly smile worried me almost as much. “Well,” he said, with a tiny shrug, “I know you have to check in with the A-1 branch there, time to time.”

“There will be some of that. But I’m also planning to pry my son loose from my ex-wife and have a little fun. We haven’t been to Disneyland yet.”

“How old is Sam now?”

“Eight.” Like he was interested.

Now he got a sly look going, with a pipe stuck in it, puffing away like the Little Engine That Could.

“Did you really think, Nate, that all I had in mind was recruiting you as a delivery boy?”

Bravo jumped down, sensing trouble.

I said, “Well, one can always hope.”

The sly look disappeared and something as grave as the expression on a judge, about to pronounce a sentence of death, came over the pudgy face. “Do I have to tell you that the polygraph test we really need our four experts to administer is of Sam Sheppard himself?”

“It’s the obvious next step,” I said. I wiggled a forefinger at him. “But that sounds like where you come in.”

He nodded. What is it about a nod from a guy puffing a pipe that gives it extra weight?

“I have to approach the warden where Dr. Sam is incarcerated,” he said, “to request the test. He’s likely to say no—he wouldn’t want every prisoner in the place to start asking for such testing—but that’s where I have to start.”

“Then what? The governor?”

Another weighty nod. “The governor of the great state of Ohio is almost certainly where we’ll end up. He can make it happen.”

“Frankly, Erle, I’m not sure I see where you’re going. Like I said, lie tests are inadmissible. Remember?”

“Of that I’m well aware. But if Sheppard passes, then the Court of Last Resort will throw all its resources at the case. And, remember—in a situation like this, it’s the public who ultimately pushes the legal system into doing the right thing.”

“The real Court of Last Resort.”

He jabbed the air with the pipe tip, putting a period on my sentence. “Precisely. Of course, it would be nice to have something to back up these polygraph results.”

“Such as?”

“Some fresh investigatory results.”

Which was where I came in.

“You want me to go to Cleveland,” I said, “and dig into this thing.”

He smiled just a little. It was disarmingly boyish coming from such a grandfatherly type. “Why, are you volunteering, Nate? Don’t you have enough crime on your hands already?”

“Don’t you?”

The boyish look left. “I’m not some commanding officer, who tells a man to volunteer. I understand you’re busy, and this is pro bono work, much of it coming out of your own pocket.”

I waved that off. “No, I volunteer, all right.”

That made him blink. Not an easy thing to do with this guy. “You do? I was expecting to have to do some arm-twisting.”

“Actually, Erle,” I said, regretting only a postponement of the Disneyland visit with my son, “I’ve been interested in this thing from the start.”

Another blink! “Really?” he asked. “Why is that?”

I shrugged. Two dogs, a chipmunk and a coyote looked at me, intrigued. “The murder happened in the early morning hours of July 4, 1954—correct?”

“Correct.”

I shrugged. “Well, I was there.”

“Where?”

“Cleveland. But to be specific, I was in that house—the murder house—later that morning.”

Gardner’s eyebrow climbed.

“Nate,” he said, “if I were writing this? This is where I’d end the chapter.”

Copyright © Max Allan Collins

Pre-Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

This is a great start to what appears to be another great Heller novel.