opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

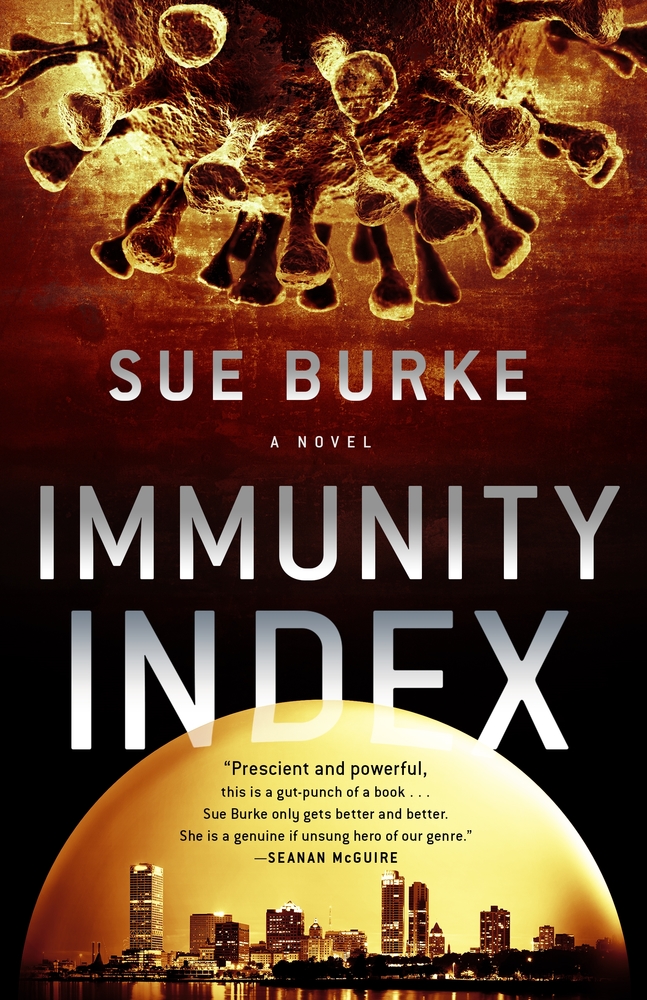

Sue Burke, author of Semiosis and Interference, gives readers a new near-future, hard sf novel. Immunity Index blends Orphan Black with Contagion in a terrifying outbreak scenario.

Sue Burke, author of Semiosis and Interference, gives readers a new near-future, hard sf novel. Immunity Index blends Orphan Black with Contagion in a terrifying outbreak scenario.

In a US facing growing food shortages, stark inequality, and a growing fascist government, three perfectly normal young women are about to find out that they share a great deal in common.

Their creator, the gifted geneticist Peng, made them that way—before such things were outlawed.

Rumors of a virus make their way through an unprotected population on the verge of rebellion, only to have it turn deadly.

As the women fight to stay alive and help, Peng races to find a cure—and the cover up behind the virus.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of opens in a new windowImmunity Index by Sue Burke, on sale 05/04/21!

Chapter 1

I, Peng, designer of life and master of its language, began my day tasked with the unsealing of a package of dead chickens. Three chickens, to be precise, sent express from a farm in Iowa to the lab in Chicago where I labored. My life had come to that, and I hoped it would not grow worse. I still had much to lose. Every day I looked death in the eye and quaked.

To stave off impending disaster, I activated the armatures inside a biosafety cabinet to slit open the seals of the package. I sat on the safe side of the glass window. A coworker stood next to me, as was protocol, and offered encouragement; we took turns doing the physical donkey work, a small act of mutual kindness to share the burden. We were about to perform a crucial task. Together, we would discover exactly what had ravaged a distant flock of chickens to determine whether it would also ravage the Earth and all of its biota.

“Wanna bet what it is this time?” my fellow donkey asked.

The armatures eased out the half-grown chickens, their feathers soaked in blood. I shuddered. Life offered splendor, death only repulsion.

“You okay?” the donkey asked.

“I feel better when they send vials of fluids.”

“Me, too. Someday this job is going to make me puke.”

A minimum of two people worked in the lab at any given time, but the exact staff varied by the day, as did the shift, depending on who was available and how much work there was. We were contract donkeys, all pretty much alike. Efficient. Skilled. Reasonably friendly and often enjoyably snide. Willing to take turns on the most disagreeable jobs, like handling bedraggled blood-soaked chickens. Bored out of our minds despite the urgency and terror, but we needed to earn a buck, so we were doing this until we could find something better. Although I might never find a better way to hide.

I said, “Given all the blood and detached heads, I conclude that they died of knife wounds.”

She laughed. Today’s fellow donkey was a middle-aged woman, a refugee from flooded New Orleans, one of the few from that disaster who had been allowed to relocate while the rest languished in ghastly camps. She was wasting enormous talents in this job—and she had just asked me the most worthwhile of questions: What was it this time? The specific answer—the specific cause—meant life or death. If a flock of fowl (or some other assemblage of livestock) fell ill, farm managers would slaughter and incinerate the animals. Or they would douse them with some kind of treatment that might be worse than the affliction but would cut their losses.

If we had reason to believe that the answer we found could endanger more than just that flock or species, we could try to trigger a national or even worldwide emergency, for all that shamefully underfunded public health services could do. Meanwhile, we would all pray, stiff with fear, asking our various gods to keep us safe from everything being created by nature or fools with gene-splicing labs in their garages. Major havoc was being wreaked in too many places. Inevitably, and no doubt soon, it would reach us. (You might think that all this responsibility would be reflected in our paychecks. No.)

“I’ll collect some of the blood for analysis,” I said for the record.

She made a note. “We’ll get external material in the blood, too. Feces might add special flavor notes to the final dish.”

“A full autopsy would be wise,” I added. That was the running joke. It was always true that we ought to be performing a more in-depth analysis, especially given our usual findings.

“Not in the budget.” That was the cynical punch line, although obsolete. Budgets had increased lately, but it was soothing to think that closer scrutiny hadn’t become our anxious routine.

“A safe bet,” I said, “would be avian infectious bronchitis.”

“Yeah, a safe bet for big operations.” She hated big farming operations, although we owed our jobs and dinners to them and the flabby lumps that chickens had been overbred into.

I gave the machine a few commands, then checked the electronic label. “These were free-range chickens. Outdoors. Maybe they got it from wild birds.”

“I heard that chickens outnumber wild birds in Iowa.”

“That’s the most disastrous thing I’ve ever heard. We took all of nature and overran it with chickens.”

“I can top that disaster. The Sino cold.” After a moment, she added, “Sorry. I hope that isn’t a problem for you.”

Yet another epidemic had befallen China, and anyone who looked Chinese might be shunned. Or murdered—apparently some misguided patriots considered homicide an effective vaccine. Unfairly, too, since that coronavirus had been traced down to a wild boar carcass revealed by thawing permafrost in Siberia, nothing Chinese about it, and China had responded fast and well. Borders had slammed shut like guillotines, the population frozen in place by quarantine, medical procedures applied with rigor and success. But everyone was jittery about epidemics, China was an enemy, and slander was a potent weapon. She knew me by my official name, Huning Li, not my artistic name, Peng, but both were unequivocally Chinese.

And she saw my broad, elderly man’s face and heard a slight accent I tried but could never erase. With my wispy white beard, I could pass for Confucius rather than Peng, and as Peng, I had once been known as a lovely woman. Gender presentation ought not to serve as concealment, it ought instead to serve as one’s genuine identity, but a bullet in a lung can lead to desperate measures. I, founder and CEO of SongLab, designer of life and master of its language, was protected from death by that glass wall and from my creditors by bankruptcy, but little stood between me and fools.

“We face death in many ways,” I said.

“A new one every day.” She then entertained herself, but not me, by reciting some of the known pathogens threatening our health or food supplies. Her tasks during that shift included a sample of feces from sick pigs, and she would soon set about examining it.

Then three soil samples arrived by certified courier and were dropped off in the airlock to our clean room. Did the soil contain the fungus that was blighting bean crops in Mexico? Urgent question. I took some cultures. Common cloned strains of beans offered no resistance to this fungus. Evil genetic engineering and the evil nature of cloned crops (not irresponsible practices by profit-hungry corporate farms) had endangered the world’s food supply, and by extension, me and the children I had once genetically designed and cloned.

Rancor, thy name is Peng.

(Or the fungus could have been a targeted biological attack, but at what target? The answer was beyond my means to know, but recent turmoil had made me believe in its possibility. Rancor was always epidemic.)

As I was finishing the cultures, the cameras in the automated reception area showed a hazmat-clad courier dropping off a container marked with top-level biohazard warnings.

That was unusual.

“Received,” I said over the speakers. The courier waved and hurried out. The container cycled through the airlock into the clean room. I dropped what I was doing and opened it. Inside were ten vials of human blood. We were tasked to determine whether the bloods’ previous owners were infected with the Sino cold (a variety of delta-CoV, to be properly more technical—or better yet, Stone Age boar coronavirus).

I checked the instructions again, hoping I was mistaken.

“Who sent this?” my coworker demanded. Another very good question.

“The label gives randomized ID. Corporate knows exactly who. We’re not supposed to know.”

“I’ll let you handle those samples.” She noticed my eyes wrinkle from a wry smile behind my face mask. “Hey, I got kids.”

“Retirement can’t come soon enough for me.” I began the search for viral RNA in the blood, and if I didn’t find that cold, what would I find? Presumably the patients were ill from something awful.

By then, three hours had passed, and the chickens’ death had a cause. She looked at the report on the screen. “Avian infectious bronchitis, like you said.”

Another gammacoronavirus, a familiar foe. “Ah, but what variety? Databases want to know.”

I studied the output, then the raw data from the RNA bases. The program had compared strains and highlighted unexpected differences. “Oh, now this could be bad,” I said, master of the grammar of base pairs, seeing a potential death sentence in the wording. “Look right here.” A hologram screen created a three-dimensional representation of a protein. I rotated it. “Coronaviruses have a proofreading function, which is expressed here, and this variation isn’t in the databases. I don’t know how this segment would function. And I should.”

She gave me a side-eye. Perhaps I had said too much if I wished to remain incognito. Few people shared Peng’s skill in predicting genetic changes. Or perhaps she hadn’t wished to imagine that chickens or, worse, wild birds were coughing up mutant viruses all over Iowa.

“Then it’s a good thing those chickens are dead,” she said. “But take a look at this for bad. Parasites in the pig shit.”

I came to look. Her screen displayed an unmagnified sample that contained smooth, pale worms several centimeters long. They were twitching. I shuddered and looked at her other screen, which displayed a genetic breakdown of the contents.

“Nematodes,” I said.

“You sure?”

“I’ve seen them before.”

“I wish I had your memory.”

“I mean the worms, not the DNA.” But I lied.

“What kind?”

“The world has far too many nematodes. Perhaps Ascaris, given the size and location.”

And so they were, as she was able to confirm: big disgusting roundworms, living in pigs no less, not quite Ascaris suum or lumbricoides or anything else, so either we had a new species (for which we wouldn’t get naming rights), or a mutation (which was becoming far too common across all species for a long list of reasons), or some careless fool had been tinkering with the language of life (also distressingly common). Both pigs and humans, and perhaps other animals, could be at risk.

“How dangerous is this?” she asked.

“Veterinarians could tell us.”

After a moment, she said, “I wish they treated pig shit more responsibly on farms.”

Whatever this worm was, its propagation was only one easy mistake or minor disaster away from our drinking water.

“If a stable has burned down,” I murmured, remembering a quote attributed to Confucius, “do not ask about horses, ask about men.”

She looked at me.

“Worry about people, not animals,” I said.

“You got that right.”

By then the soil sample was ready. No fungus. (Yet. Sooner or later it would blow in on the wind.) We joyfully reported that.

She looked over my shoulder at the initial results from the blood samples. Delta-CoV had been isolated from six of the ten.

“Oh, no!” she said. “Not here!”

“They could have come from anywhere,” I said, knowing the samples were more than likely local. “And it matters which virus.”

“It’s delta,” she said like an accusation. Sino was a delta, and the only one of that genus that affected humans—so far as we knew.

“We can compare it to the Sino virus,” I offered.

She backed away, as if the virus could propagate through the screen. I worked rapt, finally able to see this monster up close. Yes, it was Sino—but no, it wasn’t. Not quite. My fingers grew cold from fear. I called up a model, then twisted and turned it and slowly grew both more and less frightened.

“Look,” I called out to her. “The neuraminidase is different. I don’t think it would be effective.” I pointed to a section of the enzyme.

“Effective at what?”

“I think the virions couldn’t get out of the cell to infect someone else.”

She gave me that side-eye again, uncertain of my competence.

“I have two Ph.D.s,” I admitted. Actually three, but one had been merely honorary and subsequently withdrawn.

“How did the enzyme change?”

“Good question.” I quickly thought of an answer. “If I wanted to make a vaccine, this could be one avenue, a sort of attenuated virus.” Rumors said China had begun development, although rumors eventually asserted everything.

Her eyes got wide. “Yeah, that would work. Shaky ethics, though.” She had a Ph.D., too. As I said, she deserved a better job than the one we had. “Who’s doing this?”

I read her the serial number of the client. “I hope they have high ethics.” We often had doubts about our clients—and in this case, I had grave doubts. Or hopes.

We filed our reports marked by the categories Urgent and Alert, and destroyed our samples (terror prodding us to noble thoroughness), and thus our workday ended with the discoveries of a mutant virus proofreader that might devastate Iowa fowl at any moment; unfamiliar and dangerous worms on a digestive tour of pigs; safe soil (for now); and damning evidence of tinkering with an enemy epidemic. When I stood up, I felt dizzy from fear.

We left the lab, housed in what resembled a dreary warehouse in a part of Chicago notable for its dreary warehouses, and we went our separate ways. I enjoyed the warm evening air on my fear-chilled fingers. I wanted to go to the elevated train stop because I liked human company and got too little of it, aware more than ever that we could all die far too soon for no good reason. Sharing a train car with other passengers would bring me comfort. But as I waited for the train that evening, I heard a child’s voice.

“Look! Is he sick?”

I didn’t hear the response and instead decided to travel by other means and in safety, alone except for wraiths of fear and a never-vague memory of the feeling of a bullet piercing my chest. I left the platform, descended the station’s quaint old steps, and outside on the sidewalk, I raised my phone to call an autocar.

A man wearing military fatigues approached. “Dr. Li?”

This wasn’t going to be good, and lying wouldn’t help. “Yes,” I said.

“Could you please come with me?”

Fighting wouldn’t help, either. I canceled the call. “Of course.”

“Thank you,” he said. “I want you to know you aren’t in any trouble.”

I didn’t trust his words. Confucius and I both believed in benevolence. In his long life, he had suffered exile, arrest, and attempted assassination. I was already too much like him.

Copyright © Sue Burke 2021

Pre-order Immunity Index Here

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window