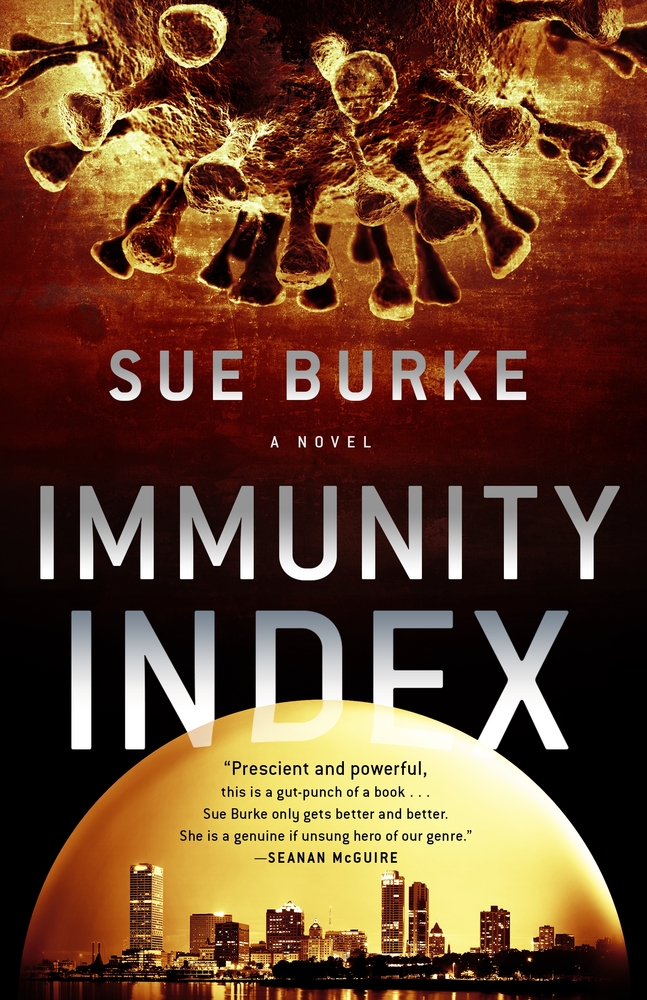

What is it like to have a pandemic book come out…in the middle of a pandemic? Sue Burke, author of opens in a new windowImmunity Index, talks about her latest novel, living through a pandemic, and more in the below guest post. Check it out here!

What is it like to have a pandemic book come out…in the middle of a pandemic? Sue Burke, author of opens in a new windowImmunity Index, talks about her latest novel, living through a pandemic, and more in the below guest post. Check it out here!

By Sue Burke

At the end of February in 2020, I bought a little extra food and a little extra toilet paper. Not a lot. I was trying to be reasonable, even though I was terrified.

I had just begun final edits to my novel Immunity Index. I’d started it two years earlier, and the plot included… a coronavirus epidemic. At the time, it seemed like a good idea. If science fiction often examines the present disguised as the future, we knew one thing for certain in 2018: sooner or later, an epidemic, even a pandemic, was coming.

I’d been through epidemics before. When I was about six years old, my parents took me to a mass public health clinic to eat a soggy sugar cube in a tiny paper cup: a polio vaccine. A year later, like most of my classmates, I got chicken pox and was miserable, with pox in my hair, on the soles of my feet, and everywhere in between.

Two years after that, my mother took my brother, sister, and I to the local health department to get blood drawn because something called measles was coming. Soon it arrived, burning through my school. A boy a grade ahead of me died. At one point the fever made me hallucinate. Never throw up when you’re hallucinating. When we were well, although I was still emotionally traumatized, my mother took us to have blood drawn again “so they can see what changed in your blood and figure out how to keep other kids from getting sick.” I was proud to help.

In the 1980s, as a journalist, I covered AIDS, which had begun to appear among gay men. I learned a lot about viruses—and about who matters politically. I wrote obituaries and reported on funerals, sometimes weeping as I typed. I first heard of Dr. Anthony Fauci.

In 2018, with a novel in mind, I began researching epidemics. It was depressing. Ed Yong’s article in the July-August 2018 issue of The Atlantic hurt the worst. “The Next Plague Is Coming: Is America Ready?” Short answer: no. We had invested vastly less than we should, he wrote, and yet a repeat of something like the 1918 Spanish Flu would cost hundreds of billions of dollars. (Covid-19 has actually cost $16 trillion, according to a pair of Harvard economists. Ed Yong turned out to be an optimist for once.)

Still, public health authorities had been trying to imagine how to prepare. A 2006 Health and Human Services report recommended stockpiling surgical masks. A 2014 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report discussed social distancing. Every document, especially those with recommendations based on the 1918 flu epidemic, called one thing essential: tell the truth so the public will know what to do. “Success relies upon open, honest, transparent, and clear communications,” opens in a new windowsaid the US Health and Human Services Pandemic Influenza Plan, 2017 Update.

In 2018, I didn’t have to imagine government leaders failing to tell the truth.

These plans, however, all expected an influenza outbreak. I chose a coronavirus, usually the cause of the common cold, because it can be deadly, as we had recently seen with SARS and MERS. Even the common cold can kill.

So I wrote a novel, then rewrote it several times, tying together four separate plot strands, shortening the timeline, and heightening the tension. And I killed a lot of people, as I tend to do in my fiction. But fictional deaths are one thing.

On March 11, 2020, I got a hair cut in anticipation of some upcoming events, just in case. By the end of the day, those events were being called off. A few days later, toilet paper disappeared from local stores. On March 15, I began self-isolation. I was 65 years old, and the news terrified me.

Regardless, I had to work on that novel. I also keep a personal journal. I wrote in March, 2020, that I was a feeling depressed. The nation would not be ready. I noted with horror that in Madrid, Spain, where I used to live, the ice rink had become a morgue. During the following month, I wrote that I felt glum, irritable, fidgety, weird, nervous, and even hopeless.

On short neighborhood walks, I saw closed businesses, the plants in the windows slowly dying. A nursing home down the street needed PPE, so I donated a box of nitrile gloves I happened to have. I turned in the manuscript and had more time to feel pointlessly angry.

Finally, on May 6, I wrote: “I realized today why at times it felt upsetting to be writing this book while Covid-19 was raging: the book portrays a better situation than our reality, and it has a happier ending than what we might face. This is a grim book, but maybe not a dystopia by comparison.”

My fiction was better than my reality. That gave me nightmares—especially knowing that it didn’t have to be this bad.

I am not writing this to ask for sympathy. Save it for others. I’m fine. I hope you are, too. My loved ones and I got through this relatively unscathed. No one died. Our finances survived. For too many people, this pandemic has meant disaster after disaster. I live next to a food pantry, and the line continued to grow all last summer. Things kept getting worse—far worse than initial expectations.

So I gave what I could to help others, distracted myself with some fine books (thank you, Tamsyn Muir), protested with great social distancing for Black lives, and attended some online events and science fiction conventions that tried hard to be enjoyable. I muddled through. If leggings count, I always wore pants. Now, I am vaccinated and waiting for my husband to be fully vaccinated so we can resume a normal-ish life. I want to hug people again, and they tell me on Zoom that they’re ready and waiting.

This hard year left us all hurting. Far, far too many people are dead, needlessly.

In the end, I learned that things viewed in the convex mirror of imagination may be closer than they look. We’re always writing about the present, sometimes too much about the present. And we’re writing about the past, too.

My book is set partially in my home town, Milwaukee. In 1918, the leadership of the Wisconsin and Milwaukee boards of health quickly spotted the threat of the coming influenza. They closed schools, theaters, and other public gathering places. Milwaukee’s Socialist mayor, Daniel M. Hoan, made public health a city priority. Flyers were passed out in poor, crowded, and immigrant neighborhoods in a variety of languages. Boy Scouts put up posters and placards. An emergency hospital was set up in the City Auditorium, staffed by student nurses and instructors from the Wisconsin Anti-Tuberculosis Association. Young women wealthy enough to have access to automobiles volunteered to drive them as ambulances.

As a result, Milwaukee, despite its especially dense population and high proportion of immigrants, lost 2 to 3 residents per 1000; the national average was 4.39.

We didn’t need to suffer as much as we have in this pandemic. But you already knew that.

Sue Burke is the author of the award-winning novel, opens in a new windowSemiosis. opens in a new windowImmunity Index is out from Tor Books now.

Order Immunity Index Now:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window