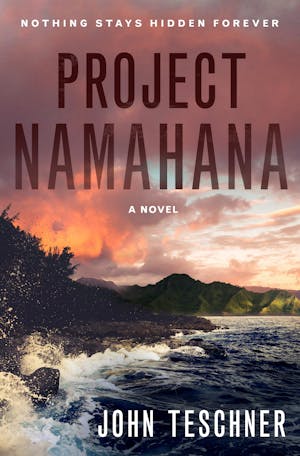

Everyone loves a good villain: the scheming mastermind, the taunting bully, the monster under the bed. However, real world evil often stems not from one individual, but from a long line of people making small, selfish decisions. In his upcoming thriller Project Namahana, John Teschner casts a corporation as his antagonist and asks the question, can a person make evil choices without being evil themselves? Read on for Teschner’s thoughts on life changing books, his experiences in the Peace Corps, and the subtleties of structural violence.

Everyone loves a good villain: the scheming mastermind, the taunting bully, the monster under the bed. However, real world evil often stems not from one individual, but from a long line of people making small, selfish decisions. In his upcoming thriller Project Namahana, John Teschner casts a corporation as his antagonist and asks the question, can a person make evil choices without being evil themselves? Read on for Teschner’s thoughts on life changing books, his experiences in the Peace Corps, and the subtleties of structural violence.

By John Teschner:

All of us have certain “Before and After” books that abruptly changed how we see the world. Sometimes so thoroughly, it’s easy to forget we ever saw things differently.

For instance, after 30+ years of being a know-it-all, I became slightly less obnoxious in 2014, thanks to a lesson on why that attitude could get me killed, courtesy of Laurence Gonzales’ profound book Deep Survival – Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why:

A closed attitude, an attitude that says, ‘I already know,’ may cause you to miss important information. Zen teaches openness. Survival instructors refer to that quality of openness as ‘humility.’

This February, I was reminded of another Before and After book when I saw the news that Paul Farmer, the founder of Partners in Health, had died unexpectedly.

In 2005, I borrowed his book, Pathologies of Power, from a Peace Corps buddy during our second year as volunteers in a poorly-conceived HIV education initiative serving the Kenyan public school system. Like most HIV interventions at the time, our work focused on prevention and personal responsibility. We were told that when Kenyans asked us why anti-retroviral drugs that were widely accessible in the US were not available to them, we should say these drugs had side effects the Kenyan health system wasn’t capable of managing. In other words, it was no one’s fault—at least, no American’s fault—that a treatable disease in one country was a death sentence in another.

The hollowness of that claim became obvious when PEPFAR–George W. Bush’s anti-AIDS initiative—made anti-retrovirals widely available in Kenyan clinics. There was no more mention of the side effects. This was vivid confirmation of Farmer’s point in Pathologies of Power: the suffering caused by systemic inequities is no different from suffering caused by more obvious sources—both are acts of violence.

Just because no individual had made a deliberate choice to cause the suffering of Kenyans with untreated AIDS, it didn’t mean no one was implicated. In fact, we all were.

The term for this is Structural Violence, and once you see it somewhere, you start recognizing it everywhere—sometimes in literal structures, like the interstate highways constructed in the 50s and 60s that deliberately demolished and isolated prosperous black communities. It soon becomes clear that while clear-cut forms of violence—murder and war—fill up the headlines, the vast majority of human suffering is caused by structural forces with no obvious guilty party.

This, obviously, is a challenge for novelists.

The novel, by definition, chronicles the individual experiences of a small cast of characters. A novel has stakes because characters’ decisions have concrete results with a moral dimension. The more directly a decision is linked to a result, the more entertaining the story: Mark decided to hit Sam. Sam fell down. What happens next?

The more links we add between decisions and results, the less compelling the story becomes. Villains become harder to identify. Heroes’ work becomes more mundane. We are in the realm of politicians and lawyers, not detectives and spies.

My first novel was inspired by a NYT Magazine story of structural violence: for decades, as told by Nathaniel Rich, DuPont factories dumped toxic chemicals in West Virginia streams, abetted by permissive regulators and a corporate bureaucracy that distributed the action of poisoning other human beings into a chain of indirect decisions carried out by hundreds of employees. The hero was a lawyer, and the story played out primarily in conference rooms and courthouses.

The article is compelling. And authors like Rich, Michael Lewis, and John Carreyrou have shown you can turn these stories of structural violence into riveting narratives.

But can you make them a thriller? That was the goal I set for myself.

First, I had to understand how these structures actually function. From the sociologist Robert Jackall, I learned corporate managers make directives as vague as possible, forcing those lower down the chain to make ever more concrete decisions. And from Stanley Milgram, I learned it’s human nature to shift our model of morality when following orders, justifying actions we would never do on their own.

So, in Project Namahana, I plotted a series of events that tear down the distance between a powerful executive and the consequences of his decisions. Over the course of the novel, Michael Lindstrom is thrust into direct contact with the kind of violence his company had been doling out in a more or less legal and socially acceptable way for decades.

One of my goals was to understand why a good person can make decisions that cause so much harm. In fact, I wanted to do more than understand; I wanted to enter the characters’ perspective and force myself and my readers to ask whether we have similar self-deceptions.

After all, there’s another reason we choose clearcut stories of heroes and villains over narratives of complex social forces: it’s not just their entertainment value, it’s the fact that we all want to identify with the hero. And stories of structural violence force us to ask whether we may sometimes be the villain as well.

Click below to pre-order your copy of Project Namahana, coming June 28th, 2022!

Did 3 boys actually die on Kauai from a polluted stream around the 1980’s?