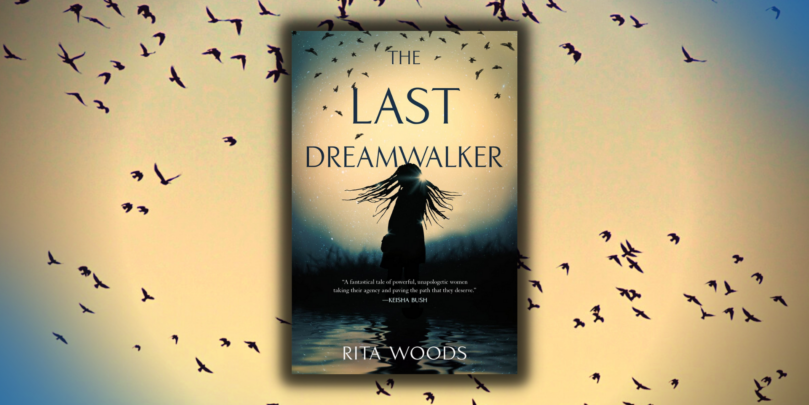

From Hurston/Wright Legacy Award-winning author Rita Woods, The Last Dreamwalker tells the story of two women, separated by nearly two centuries yet inextricably linked by the Gullah-Geechee Islands off the coast of South Carolina—and their connection to a mysterious and extraordinary gift passed from generation to generation.

From Hurston/Wright Legacy Award-winning author Rita Woods, The Last Dreamwalker tells the story of two women, separated by nearly two centuries yet inextricably linked by the Gullah-Geechee Islands off the coast of South Carolina—and their connection to a mysterious and extraordinary gift passed from generation to generation.

In the wake of her mother’s passing, Layla Hurley unexpectedly reconnects with her mother’s sisters, women she hasn’t been allowed to speak to, or of, in years.

Her aunts reveal to Layla that a Gullah-Geechee island off the shore of South Carolina now belongs to her. As Layla digs deeper into her mother’s past and the mysterious island’s history, she discovers that the terrifying nightmares that have plagued her throughout her life and tainted her relationship with her mother and all of her family, is actually a power passed down through generations of her Gullah ancestors. She is a Dreamwalker, able to inhabit the dreams of others—and to manipulate them.

As Layla uncovers increasingly dark secrets about her family’s past, she finds herself thrust into the center of a potentially deadly, decades-old feud fought in the dark corridor of dreams.

The Last Dreamwalker will be available on September 20th, 2022. Please enjoy the following excerpt!

CHAPTER ONE

SPRING

The day before her mother’s funeral it rained—alternating between a determined downpour and a vague, half-hearted mist that covered the city in a twilight haze long before actual nightfall. As Layla pulled her car into the driveway just after eleven, it was still raining.

She killed the engine and sat, staring through the windshield at her mother’s house, the only light coming from a streetlamp near the end of the block. It’d been months since she’d been on this street, and yet, even in the hazy darkness, everything looked exactly as it always had. The newspaper soggily perched in the Pryors’ bushes. The mound of damp leaves piled at the edge of the Calhouns’ curb. The Browns’ bright yellow Hummer parked in its usual spot next door, taking up an obscene amount of street real estate. The lawns all neat and well cared for.

She twisted a strand of hair round and round her finger. There was not a single thing in the world she would’ve rather done less than go into that house. Finalizing the arrangements at the funeral home with Will, she’d offered to pick up their brother Evan and his family from the airport, or to drop the programs off at the church, or to check in with the caterer about the repast.

Anything.

Anything else but this.

Instead the single task she’d been given for the funeral had been to go to the house and retrieve the pink crystal heart brooch their father had given their mother, the one piece of jewelry Elinor Hurley was never seen without, and make sure it got to the church in time for the service.

Layla’d argued with her brother, suggested someone else should get the brooch, said it was ridiculous to drive all the way to their mother’s and hunt for the brooch with so much else to do. But Will had gotten that look: eyes narrowed, his full lips clenched so tightly she could see the muscles spasming in his jaw. The look that said that, once again, she was being ridiculous, that she was a disappointment.

And she’d flinched. Hated that she flinched. Hated that he could still make her feel like a badly behaved child. That he could make her feel stupid. So here she was, sitting in her mother’s drive in the middle of the night, her stomach a clenched fist beneath her rib cage.

Muttering an obscenity, she pushed herself out of the car and dashed through the rain to the front door. On the narrow porch, she unconsciously touched the bottle nestled in the branches of the holly bush that framed the railing. For as long as she could remember, her mother had insisted there always be a bottle in the tree by the door: to catch the evil spirits that came in the night, she said.

Blue.

Because blue attracts the evil spirits and once caught inside, they couldn’t get out.

One of Layla’s earliest memories was of her and her mother on this porch, the scent of her mother’s perfume, as they bent together just after sunrise to check the bottle. Listening for the telltale hum that would indicate the presence of an evil spirit trapped inside.

Hunching her shoulders against the rain, she struggled to open the door but the key wouldn’t turn.

“Damn it, Mom!” she swore.

The lock had stuck for forever, since before her freshman year of high school. How many times had she reminded her mother that it needed to be fixed?

The realization struck her like a blow that she would never again have to complain to her mother about the lock—or about anything else—and for a long moment, she stood shivering on the porch, oblivious to the rain soaking her hair, running down her face. Swallowing hard, she tried the key again, with the same result.

“Shit,” she screamed.

Kicking the door in frustration, she fought the urge to throw herself down onto the small porch and wail at the top of her lungs, neighbors be damned. Instead, teeth clenched, she stomped toward the back of the house, her tennis shoes soaking up water as she squished through the wet grass.

The back door opened easily, and Layla stepped into her mother’s kitchen. Wet moonlight spilled through the window over the sink, turning the black granite countertops a shimmering silver. The faint scent of coffee and vanilla, and her mother’s perfume—Chanel No. 19—hung in the air. She kicked off her wet shoes, scrunching her toes to keep from slipping on the smooth tile floor. Her heart fluttered fast in her chest, and she forced herself to take slow, deep breaths as she moved through the house. In the dining room, the table was covered with pies and cakes and homemade breads dropped off by neighbors and friends, mingling the aroma of yeast and butter with her mother’s scent.

Her mother was everywhere in the house: watching, disapproving. Disapproving of what? It didn’t matter. If her mother was watching, she was disapproving: of Layla’s hair, of her job, of the fact that she never wore pantyhose.

Stopping just long enough to pour herself a glass of wine from the wine rack, Layla reluctantly made her way down the hall toward her mother’s bedroom. The last time she’d been in this house had been nearly two months before. As usual, she and her mother had argued. She couldn’t remember now how it started, most likely the way it always did, with her mother criticizing something she’d done, or hadn’t done; with her offering to get Layla a “real” job teaching at one of the schools so that her education, her “talent” wasn’t completely wasted.

Layla may not have remembered how it started but she remembered with painful clarity how it ended.

Her mother’s voice—hard, the consonants sharp, clipped—seemed to still ricochet in the shadow-filled hall.

“It’s time to grow up, Layla. Compromise is what grown-ups do. Dreams are for children. There are things you have to give up as an adult because there are things that need to be done to survive in this world.”

“I am surviving, Mom. And I still have my art.”

“Art?” Her mother’s laugh had been like a physical blow, the sound like wind-whipped sand against her skin. “That’s not art. If you’re going to settle, Layla, at least settle for a job with dental insurance.”

Even now, all this time later, Layla could feel the way her lungs had constricted in her chest, forcing out all the air

“You would never say something like that to Will,” she’d finally managed, barely recognizing her own voice. “Will dreamed of being a dancer and he’s a dancer.”

“Choreographer,” snapped her mother. “And women don’t have the luxury of indulging their fantasies the way men do. Women have to live in the real world.”

Layla had stared, open-mouthed.

“Loving something, doing something that makes you feel whole inside yourself, isn’t real?” she said slowly, trembling with rage. “I feel so sorry for you, Mom. To have spent your whole life living a halfway life. Living a life without a single dream!”

Layla’d stormed out of the house. Those were the last words she’d ever speak to her mother. Her mother had called the next day and the day after that. Had left voice messages inviting her to lunch at the Florida Avenue Grill, asking her to drop by the museum for coffee. Her version of a truce, of an apology. But Layla had ignored her, ignored her brothers’ pleas to just move on. The wound inflicted by this latest argument was too raw, too deep. She hadn’t expected her mother to die. Her mother couldn’t die. Elinor Hurley was a force of nature, indestructible, like the wind, or lightning. Dying was simply an impossibility.

Now, back in her mother’s house, Layla fumbled in her trench coat pocket, hands shaking, until she found what she was looking for: the little blue pills. The pills for her anxiety. She hesitated. She’d already taken one earlier in the day at lunch.

A small voice whispered in her mind that she was taking too many of them lately, but she shook that voice away and popped a pill in her mouth, washing it down with a large gulp of wine. She closed her eyes and pressed her back against the wall, inhaling deeply through her nose. She waited, motionless, until she began to feel that familiar unspooling in the pit of her stomach, until she felt the weight of the world rolling away from behind her eyeballs.

Sighing, she opened her eyes and pushed open the door to her mother’s bedroom, flicking on the light. The champagne satin duvet was neatly folded on the end of the bed, as if her mother were simply spending the night somewhere else and would be returning in the morning. Through the half-open closet door, Layla could see shoes neatly stacked in their boxes, clothes meticulously arranged by color. Everything in its place. Everything perfect.

A wave of light-headedness washed over her.

Just get the brooch and go, she thought, setting the glass on the dresser. Just get it and get out of this house.

The jewelry box sat in the center of the dresser, a large silver box inlaid with mother-of-pearl. She lifted the heavy lid and managed a half smile. Her mother was nothing if not a creature of habit. The heart lay right on top, nestled on a square of white velvet, the facets throwing off shards of pink light. She ran one finger lightly over it, feeling the irregular shape under her fingertip.

She’d been six when her father had woken her late on Christmas Eve night, still wearing his heavy coat. She could smell the cold on him, mingling with the scent of cigar smoke and the Old Spice cologne he always wore, all of it merging into the smell that was uniquely her father’s.

“Do you think your mother will like it?” He held out a small box. “It’s Swarovski crystal.”

Her breath had stopped. In the moonlight streaming through her window, the crystal heart shimmered, seeming to faintly pulse in its white velvet nest, as if it were an actual living thing. She hadn’t known what Swarovski crystals were, but she was still young enough to believe in magic, and this heart had clearly come from the land of dragons and fairies and princesses. She nodded. Of course her mother would like it. How could she not?

And she’d been right. Other than her wedding ring and the ornate silver cross she wore on a chain under her blouse, the crystal heart was the only other piece of jewelry her mother always wore.

Layla picked up the heart, velvet square and all, and pushed it into her pocket before backing from the room and closing the door. In the hallway she stumbled and reached to brace herself against the wall. She felt watery, as if her spine, her legs, were turning to jelly. She frowned. The pills didn’t usually hit her so hard, so fast.

“Shit!” She suddenly remembered.

That hadn’t been the second pill of the day. It had been the fourth . . . or maybe the fifth. She couldn’t remember anymore. There’d been the one at lunch. But also, the two she’d dry swallowed in the parking lot right after storming from the funeral home. Three pills in two hours. The little voice was nagging at her again.

“It’s fine,” she muttered to the empty house. “It’s fine.”

Without the pills she couldn’t sleep. Without sleep, she could barely make it through a day. They just calmed her, made her feel more like herself. And her mother had just died, so of course she was taking them. Maybe a few more than usual, but who wouldn’t under the circumstances?

She squinted at her watch. Blinked in confusion. Along with everything else, she was losing track of time. It was twelve thirty; “half past middle night” her mother would have said. Standing in the darkened hallway, she debated whether or not to risk the forty-minute drive back to her apartment. She shook her head, trying to clear it, and the floor swooped sickeningly beneath her feet. She grabbed, once again, for the wall.

She did not want to spend the night in her mother’s house, but she doubted she’d make it to the end of the driveway like this. She should lie down, just for a few minutes, let the medicine wear off a little. This house, her mother’s house, might be filled with ghosts, but Layla didn’t really believe in ghosts anyway, did she? Especially not with that little blue pill coursing through her veins.

She gave a harsh laugh and walked unsteadily down the hall to her old bedroom, the room she’d slept in as a girl. Stepping through the door into the room, she winced.

When she was fifteen, she’d insisted the room be painted a deep eggplant hue because the color felt powerful, royal. Now the walls were a soft, pastel pink, the curtains a delicate lace. But aside from the color, it was exactly as she’d left it the day she’d gone away to college: louvered French closet doors, the paisley patterned cushion on the rocking chair. Swimming trophies lined the top of the bookshelf; a small stuffed lamb, her favorite childhood toy, lay curled in the center of the rocking chair. Layla knew without looking that behind those louvered doors were old art books, neatly boxed, the dress her mother had forced her to wear to the prom she hadn’t wanted to go to.

Acid rose in the back of her throat, and she swallowed hard.

Pulling a knitted afghan from the back of the rocker and wrapping it around her damp shoulders, she stared at the room. Since flaming out of art school four years before, she’d only spent a handful of nights here, preferring to couch surf with friends or spend a few nights here and there with Will, until she’d found her own place. One more thing she and her mother had exchanged heated words about.

On a whim, she pulled open the louvered closet door. Pushing aside the clothes, she let out a pained groan. It was still there, tucked deep into a back corner. Their Adventure box.

Layla sank to the closet floor and pulled it close. The pale wooden box was six inches high and eighteen inches wide. Lifting it into her lap, she was surprised by the unexpected heaviness of it. She lightly stroked the plain, unornamented top, sadness, grief, anger roiling together inside her. This box contained the best of her and her mother, their happiest memories.

Hands trembling, she lifted the lid and let out a shaky laugh. Like everything else her mother did, the contents had been painstakingly arranged. Photos, menus, store flyers, receipts, bundled together and organized by date, everything tied neatly with a thick purple ribbon.

Layla plucked one bundle from near the bottom. Their trip to San Francisco from when she was about nine. There were receipts from Eastern Bakery in Chinatown and the cable car, a grease-stained menu from Zuni Café. And there, a picture of her and her mother on the Golden Gate Bridge, her mother’s green silk scarf swirling around her face in the gale force wind. Layla remembered that day. Remembered how terrified she’d been at the high, wide-open view from the bridge, how cold and miserable she’d felt, and it showed in the picture. She remembered her mother had only been able to coax her to walk the length of that bridge with the promise of cake and hot chocolate at Ghirardelli’s.

She picked up another bundle and then another. New York, Mexico, Montana, London, Rome. Sometimes these adventures included her whole family, but as the years went by, usually just her and her mother. She stared at the picture, at her mother’s face. Her mother had seemed so happy on these trips, the further from home, the happier, like a completely different person. But that different, happy person always faded away once they returned home, sometimes after a week or two, sometimes in just a few days.

Layla picked up another picture. Their last trip. Her mother was kneeling before a tombstone in the Necropolis in Glasgow. Her head was bowed as she leaned far forward, making a rubbing of one of the tombstones, her white sweater seeming to glow against the grays and greens of the cemetery, the crystal heart there near her shoulder.

It had been the last time Layla had seen the laughing, carefree woman that existed now only in her memory and on bits of paper inside the Adventure box. Six months later her father had been killed. There’d been no more adventures.

Sagging under the weight of the memories and her sadness, Layla pushed the box aside and closed her eyes. She just needed to rest a minute, until it felt safe to drive, then she would get up and go home.

The rich, greasy smell of bacon woke her.

Sunday. It must be Sunday. The only day her mother allowed them to eat bacon. Too many chemicals, she said. Too much fat.

Or maybe it was the birds that had awakened her.

Not the soft cooing of mourning doves in the trees that shaded her neighborhood but something different: a harsh, aggressive sound that filled the air, her head.

She opened her eyes, and the deep purple walls—eggplant—seemed to pulse around her like a heart. She stood, following the aroma of Sunday breakfast into the kitchen. Three strips of bacon lay side by side in a skillet on the stove, past crisp, burning, but the kitchen was empty. Through the open back door, she saw her mother on the lawn, wearing her pink bathrobe, staring up at the sky.

Layla frowned; something had happened to her mother, something bad. She twisted a strand of hair around her finger, trying to remember what. Stepping closer to the door, she looked up, following her mother’s gaze. The sky was dark with birds, large black birds, their feathers iridescent in the sun. They seemed to sense Layla watching them and swooped lower, charging at the screen door before breaking away at the very last moment, their dark eyes locked on hers. Then suddenly, they were no longer wheeling away, no longer avoiding the collision. She cried out, shrinking back, as bird after bird slammed into the screen, the mesh pulling free of the frame a little more after each assault. Behind her, the burning bacon set off the smoke alarm.

“Layla.”

Her mother stood beside her. The pink bathrobe was gone, replaced by a wedding dress. Not the sleek, designer gown that Layla knew from the photo on the mantel, but an old-fashioned, overdone thing, frothy with lace and crinoline, a dress like nothing her mother would ever wear.

They were standing in a house she didn’t know. It was old: the floors warped and uneven. Doors hung crookedly in their frames, the peeling, windowless walls and the ceiling seeming to glow like a carnival fun house.

“Mom?” There was something off about her mother, something . . . wrong. Her usually flawless makeup was caked thickly atop her skin like a mask, and she seemed . . . frightened.

“I have to go,” her mother said.

“Where?”

Without answering, her mother turned and began to walk away, down a corridor cluttered with bits and pieces of decrepit furniture, seemingly oblivious as the lace of her dress caught and shredded on the edges of the half-broken things in her path. It was hot, the still air as thick as pudding. And the smell: the air smelled like the ocean.

“Who ebben you be?”

The voice came from behind her, and Layla whirled to find a tall figure—a woman—forming in the oily light of the hallway. The words sounded both familiar yet heavily foreign, the accent bright as music.

“Who ebben you be?” the woman asked again. “How come you be here?”

The woman was narrow through the shoulders, with a wide, round face and skin the color of perfect morning toast. She frowned, stepping closer. At the end of the corridor Layla’s mother stood watching in silence.

“Wait!” The woman’s gaze swung between Layla and her mother, the whites of her eyes glittering in the impossible glow of the walls. “I knows you!”

Her expression twisted, changed, settling on a place somewhere between shock and rage. The hair on the back of Layla’s neck stood up.

“Elinor?” The woman’s lips pulled back from her teeth in a snarl as she addressed Layla’s mother. “You made this here . . . thing.”

Layla took a step back. The woman followed.

“You can’t be here. You not b’long.” The woman gave a harsh laugh. “That’s what you try hidin’ all this time, Elinor? This here devil Dreamwalker?”

Layla didn’t see her move, but suddenly the woman’s face was mere inches from her own, her breath damp and hot, the smell of her oddly sweet.

“You not one a us. You not the third a three.”

Layla shook her head. “What?” she whispered. “What does that mean? I don’t know what that means.”

She tried to take another step back, but something blocked her way. A dresser? A table? She was afraid to look, afraid to turn her back on this strange woman.

“Knowed it would come to dis by and by,” hissed the woman. “Knowed it jes a matter a time. But you ain’t trick me, no. You am the devil walkin’ dreams and she can’t protect you no more.”

“Who?” cried Layla. “Who can’t . . .”

The blow stunned her, throwing her off balance. Tears of shock and pain momentarily blinded her.

“Charlotte!” Her mother was there, the front of the wedding dress bunched in her arms, her bare feet showing. Layla stared at those bare feet. “Stop it!”

“No!” screamed the woman named Charlotte. “No! You go ’way! This punkin-skin chil’ come to me! She want take me dreams? She break covenant and take me dreams? Me last dream? She want to take Ainsli Green? Not never!”

The big woman drew back her hand as if to strike again and Layla cringed. Then came her mother’s voice, whispering in her ear.

“Wake up, Layla! It’s time to wake up!”

She jerked awake, heart thrumming hard in her chest, unsure of where she was. She looked around, wild-eyed, the afghan bunched around her knees. The Adventure box was on the floor, inches away.

Mom’s, she thought, I’m at Mom’s. Today we’re burying my mother. Pale morning light from the window reached the closet where she slumped. She glanced at her watch. It was just after eight.

“Jesus hell,” she murmured. She raked her fingers through her hair and groaned. She ached everywhere, and a spot just below her left eye throbbed inexplicably with pain in time with her heartbeat.

She touched the sore place on her cheek and scrambled to her feet. There was just enough time to grab a cup of coffee before heading to her apartment to get dressed for the funeral. Head pounding, she padded to the kitchen. When the coffee was ready, she poured herself a huge cup and shuffled into the dining room, bleary with fatigue. Her stomach churned acid up into her throat, as it always did whenever she was stressed, but if she was going to get through the next hour, let alone the rest of this day, she needed this infusion of caffeine. She glanced at her reflection in the mirror over the buffet and froze.

“What the hell?”

Her left cheek was swollen, a bruise already beginning to form, a hint of the black eye to come. With shaking hands, she gripped the cup and gulped down the coffee, ignoring the scalding sensation on her tongue. It had been months since she’d had one of those dreams. It was another reason she took the pills—to keep the dreams away.

She’d had them—dreams like this—her whole life. Dreams so real that for most of her early childhood, she hadn’t understood that there was a difference from what she dreamed at night and the world she walked around in during the day.

Sometimes the dreams were nice: like when she followed Mr. Pryor to his grandmother’s house, watching from the shadows as the old woman sat humming in her rocking chair, shelling peas. Or when her grandfather taught her daddy how to catch fireflies in a jelly jar in the field behind their house in Michigan, even though he’d died when her daddy was still in college. She liked those dreams. When she had those kinds of dreams, she woke up happy.

But then there were the other ones.

The ones where she woke up bloodied and bruised. When she found herself standing alone in the dark, in the middle of a stranger’s yard. Those were the bad dreams.

And as she’d gotten older, there were fewer and fewer of the kinds of dreams where she watched the old lady across the alley dance in red sparkly slippers, and more and more where people she barely knew whispered things in her ears she didn’t really understand but somehow knew were terrible.

Growing up, Evan had listened patiently as she confessed her growing fear, rubbing her back and telling her to just think of nice things before she went to bed. Will mostly just rolled his eyes then, after a while, stopped listening to her altogether, excusing himself from the breakfast table whenever Layla began recounting her latest dream.

It was Daddy who’d insisted she go see the doctors, worried about the scratches, the bruises, the torn clothes. Night terrors the doctors called it. She’ll grow out of it, they said.

And her mother . . .

Her mother pretended it wasn’t happening. Refused to even listen to Layla’s dreams about lying in head-high grass as alligators slithered across her feet and gunfire split the air, or the scary man, his face swollen with rage, hitting the little girl with red hair who looked just like her teacher at school. Her mother always changed the subject. She would ask about Layla’s next swim meet or history test, or if she really intended to go out with her hair like that. Her mother seemed not to see the scratches, the bruises. Her mother, who saw everything.

And Layla learned to pretend too. To pretend that when she went into her room at night and lay in the bed, she fell asleep like everybody else. She learned to cover up any evidence of a bad night.

By the end of high school, she’d discovered a glass of wine, or four, helped her fall asleep, helped keep the dreams away. And now the pills, especially the little blue pills, those helped too. Sometimes weeks passed without one of those dreams, weeks when she woke feeling refreshed, feeling normal.

But not this week. Not since the call that her mother had been found lying unconscious on her office floor. Ever since then, nothing seemed to keep the dreams away. But it had been a long time. A year? More? Since they’d leaked into her waking life, since they’d left their mark on her body, her face.

I have to get out of here,” she said aloud to the empty room. “I knew staying here was just stupid! I have to . . .”

She gulped the last of her coffee and searched the kitchen for her shoes. They weren’t there. She frowned, trying to remember if she’d picked them up and taken them into the bedroom with her the night before.

Fighting panic, she walked quickly back down the hall. The door to her mother’s bedroom stood slightly ajar. She frowned. She’d closed it the night before; she was sure of it. Gritting her teeth, she pushed it open with one finger.

“No!” Layla cried, stumbling back. “No!”

Her mother’s bedroom was in shambles. Dresser drawers had been yanked out, the contents strewn across the floor, the bed. The bedside lamp lay half under the bed, the satin shade crumpled. The closet door yawned wide, and from the hallway she could see that her mother’s clothes had been ripped down and dumped in a heap on the closet floor, the hangers dangling, empty on the rod. The silver jewelry box lay upside down on the floor.

Atop the dresser, looking obscenely out of place, even in the midst of the chaos, were Layla’s black Converses, perched next to her empty wineglass. But it was the mirror that held her transfixed. Clinging to the center of the glass was a soggy picture, a page torn from some old magazine. The picture was tattered and creased, but she could still clearly see the image of the Eiffel Tower. And holding the page in place, smeared onto the otherwise spotless glass, was a muddy handprint, the mud dried to a pale gray, the handprint clearly not hers.

And the smell.

The room reeked, a strange, pungent odor, reminiscent of rotting eggs, hanging in the air. Layla made a gagging noise. She snatched her shoes from the dresser, upsetting the wineglass, then turned and ran barefoot from the house.

Click below to pre-order your copy of The Last Dreamwalker, coming September 20th, 2022!

Comments are closed.

Leave a Reply