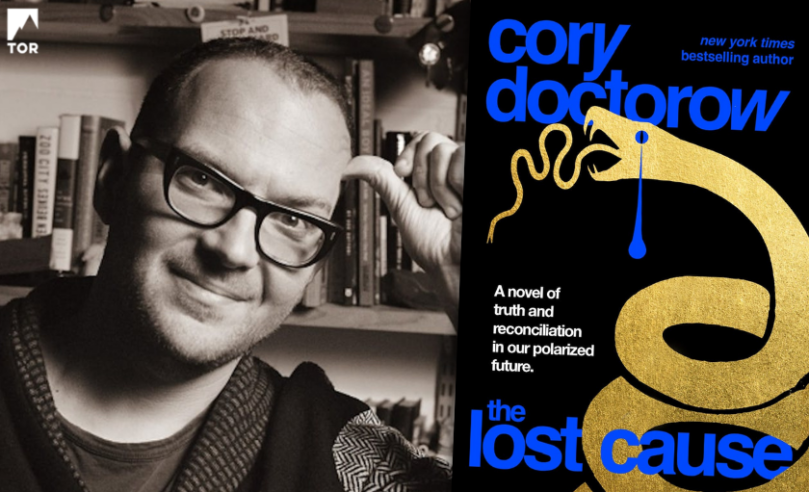

by Cory Doctorow

by Cory Doctorow

Dystopia isn’t a setting – it’s a vibe. There’s nothing dystopian about depicting a world where things are breaking down. Things break down. Assuming things won’t break down doesn’t make you an optimist – it makes you a dangerous asshole. “Things won’t break down” is the thinking that leads to “so the Titanic doesn’t need lifeboats.”

Dystopia is a society where things are breaking down – and no one will lift a finger to fix it.

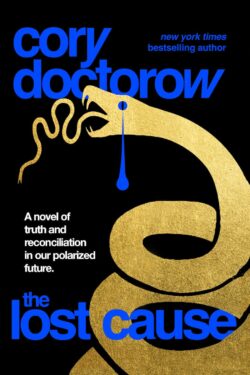

My next novel, The Lost Cause, is set in the midst of a spiraling climate crisis punctuated by mass death from zoonitic plagues, floods, wildfires, and drought. Tens of millions of Americans have become internal refugees, their hometowns wiped off the map.

It is a utopian novel.

What makes this novel of a world in worsening calamity, attended by unimaginable human suffering, “utopian?”

Simple: they’re doing something about it.

In July 2022, I wrote the following for my column in Locus magazine:

━━ ˖°˖ ☾☆☽ ˖°˖ ━━━━━━━

We’re all trapped on a bus.

The bus is barreling towards a cliff.

Beyond the cliff is a canyon plunge any of us will be lucky to survive.

Even if we survive, none of us know how we’ll climb out of that deep canyon.

Some of us want to yank the wheel.

The bus is going so fast that yanking the wheel could cause the bus to roll.

There might be some broken bones.

There might be worse than broken bones.

The driver won’t yank the wheel.

The people in expensive front row seats agree.

“Yank the wheel? Are you crazy? Someone could break a leg!”

We say, “But there’s a cliff! We’re going to go over the cliff! We’re going to die!”

“Nonsense,” they say. “Long before we go over the cliff, we’ll have figured out how to put wings on this bus.”

We argue.

They add, “Besides, who’s to say we’ll fall off the cliff? Maybe we’ll be going so fast that we leap the canyon. Fonzie did it! Calm down. Hey! Keep your hands off the wheel? What are you, a terrorist? Don’t you dare do that again. Someone could get really badly hurt.”

The climate emergency is real and we are living through it. As I write this, I’ve emailed some writer friends in the southwest to ask if the fires threaten them or their homes. One hasn’t answered yet. The other wrote back to say they’re fine, but what about the wildfires near my house?

Oh, I wrote. We’re fine. So far. California is in for a hell of a wildfire season. It’s dry out there. It’s an emergency. Officially.

(It was an emergency before, but that was unofficial)

We’re not acting like it’s an emergency. In mid-May, The Guardian reported a bombshell: a series of planned “carbon bombs” – large-scale oil and gas projects that will “shatter the 1.5C climate goal.” The war in Ukraine has the world scrambling for winter heat – for sources of oil and gas, that is, not renewable alternatives.

Of course not. The only way for renewables to replace Russian oil and gas this coming winter is for Europe to have retooled around sustainable heating: a mix of beefed up insulation, heat pumps, and mass power storage. Those are long projects. We knew we’d need them decades ago, but we kicked the can down the road, and further down the road, and further.

Incredibly, climate denial still festers. “There’s no cliff,” they insist. “This bus is on a smooth road that goes all the way to the promised land. Only a fool would swerve now.”

The good news is: climate denial is on the wane. The bad news is: deniers have pivoted to incrementalism: “We’ll fix the climate. Give us a couple decades to phase out oil and gas. Give us a couple decades to replace the cars and retrofit the houses. Give us a couple decades to invent cool direct-air carbon capture systems, or hydrogen cars that work just like gas cars, or to replace our overland aviation routes with high speed rail, or to increase our urban density and swap out cars for subways and buses. Give us a couple decades to keep making money. We’ll get there.”

In other words: “We’re pretty sure we can get some wings on this bus before it goes over the cliff. Keep your hands off the wheel. Someone could get really badly hurt.”

People are already getting really badly hurt, and it’s only going to get worse. We’re poised to break through key planetary boundaries – loss of biosphere diversity, ocean acidification, land poisoning – whose damage will be global, profound and sustained. Once we rupture these boundaries, we have no idea how to repair them. None of our current technologies will suffice, nor will any of the technologies we think we know how to make or might know how to make.

These boundaries are the point of no return, the point at which it won’t matter if we yank the wheel, because the bus is going over the cliff, swerve or no.

Focus on the swerve.

Believe it or not, the swerve is a happy ending. This is a hopeful article. Here’s what I hope we can do: I hope we can swerve.

A couple decades ago, the swerve might have been avoidable. It was 1977 when Exxon’s own scientists concluded that their products would render the planet uninhabitable for humans. Exxon knew. They buried the research and paid for denial.

George H.W. Bush came into office in 1988 as the “Environmental President.” He campaigned on “conven[ing] a global conference on the environment at the White House. It will include the Soviets, the Chinese… The agenda will be clear. We will talk about global warming.” By 1992, he abandoned the idea of the US retooling to avert the catastrophe. “The American way of life,” he told the Rio Earth Summit, “is not up for negotiations. Period.”

If we’d started in 1977, we might have paid some civil engineers to build a bridge over the cliff. In 1988, it was still entirely possible. In 1992, the option was still there.

Today, time has run out for bridges.

All we’ve got left is the swerve.

We’ve got to seize the wheel of the bus. We’ve got to plunge past the first-class passengers in the front rows of the bus, and we have to yank the wheel. We have to swerve.

The bus will roll over. It won’t be nice. We will probably have to abandon some of our most beautiful coastal cities and towns. We will probably have to retool our industries in haste, and commandeer our factories to build new energy tech instead of consumer tchotchkes – the way we ordered factories to produce vaccines and PPE last year.

I don’t know what the first-class passengers were thinking. Some of them will be dead of natural causes before the bus goes over the cliff, and they didn’t want to sacrifice any of their material comforts to ensure that the rest of us continued to live once they passed on, I suppose.

Others are just ideologically committed to traveling in a straight line. The swerve is morally bankrupt. It’s communism. The only way to get over the cliff – if such a thing exists – is to floor the bus. Go as fast as possible. Leap the gorge! The Fonz did it, right?

The swerve is our hopeful future. Our happy ending isn’t averting the disaster. Our happy ending is surviving the disaster. Managed retreat. Emergency measures.

In the swerve, we’ll still have refugee crises, but we’ll address them humanely, rather than building gulags and guard-towers.

We’ll still have wildfires, but we’ll evacuate cities ahead of them, and we’ll commit billions to controlled burns.

We’ll still have floods, but we’ll relocate our cities out of floodplains.

We’ll still have zoonotic plagues as animals flee their disappearing habitat, but we’ll apply the lessons of COVID to them.

We’ll still have mass extinctions, but we’ll save the species we can, and we’ll prioritize habitat restoration as a way of preserving our horizontal brothers and sisters (as Muir called animals) and as a way of putting the climate back in balance.

We’ll swerve. The bus will roll. It will hurt. It will be terrible.

But we won’t be dead on canyon floor.

We’ll fix the bus. We’ll make it better. We’ll get it back on its wheels. We’ll get a better driver, and a better destination.

That’s our happy ending. That’s our hopeful future.

We gotta get ahold of that wheel first. You ready?

Let’s roll.

━━ ˖°˖ ☾☆☽ ˖°˖ ━━━━━━━

That’s what the people of The Lost Cause are doing. Through hard work and hard fighting, they create the historical contingency that allows them to call themselves “the first generation in a century that does not fear the future.”

They have embraced a muscular Green New Deal that treats the emergency with the gravitas and urgency it demands. They have embarked upon a 300-year project to relocate coastal cities inland, above the rising seas’ new level. They infill their cities, making space for refugees, who are welcomed as more hands and more minds to turn to surviving the crisis. They have grabbed the wheel and they’re swerving.

Of course, not everyone is happy about this. Those first class passengers, the ones who insisted that there was no cliff, that they’d figure out how to attach wings to the bus, that if the bus went fast enough it could leap the gorge? They’re furious – and they’re rich, and they have an army of followers who see things getting worse and blame the people who are working to make them better.

This counter-revolution is a powerful alliance of domestic white nationalist militias and seagoing anarcho-capitalist wreckers, determined to snatch defeat from victory’s jaws.

The Lost Cause is a novel about what we do with the losers of a just revolution. It is a story about fierce comradeship on both sides, and the special problems of winning the fight.

Cory Doctorow is a regular contributor to the Guardian, Locus, and many other publications. He is a special consultant to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an MIT Media Lab Research Associate and a visiting professor of Computer Science at the Open University. His award-winning novel Little Brother and its sequel Homeland were New York Times bestsellers. His novella collection Radicalized was a CBC Best Fiction of 2019 selection. Born and raised in Canada, he lives in Los Angeles.

A crime would bring them together, grief would bind them and love would make them famous.

A crime would bring them together, grief would bind them and love would make them famous.

Spencer Quinn’s A Farewell to Arfs ups the ante in the action-packed and witty New York Times and USA Today bestselling series that Stephen King calls “without a doubt the most original mystery series currently available.”

Spencer Quinn’s A Farewell to Arfs ups the ante in the action-packed and witty New York Times and USA Today bestselling series that Stephen King calls “without a doubt the most original mystery series currently available.”

T. R. Hendricks’s Derek Harrington returns in The Infiltrator, an adventure of man vs wild—and the domestic terrorists hidden there.

T. R. Hendricks’s Derek Harrington returns in The Infiltrator, an adventure of man vs wild—and the domestic terrorists hidden there.