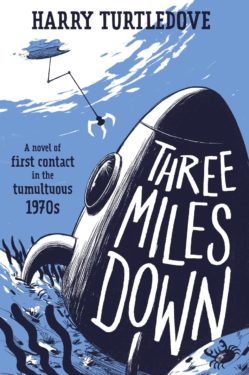

Do you love aliens in sci-fi? Are you fascinated by all the different ways extraterrestrial life can be brought to the pages of books? So does Harry Turtledove, author of opens in a new windowThree Miles Down. Check out his guest post on the topic below!

Do you love aliens in sci-fi? Are you fascinated by all the different ways extraterrestrial life can be brought to the pages of books? So does Harry Turtledove, author of opens in a new windowThree Miles Down. Check out his guest post on the topic below!

First contact between humans and aliens is one of the oldest and most enduring tropes in science fiction. The phrase itself goes back to Murray Leinster’s famous “First Contact” (Astounding, May 1945). There, We and They meet in space, in approximate equality. The interpreters on the two ships decide their races will get along with each other pretty well because they amuse each other by swapping dirty jokes. (Yes, everybody’s male. 1945.)

This kind of meeting is one of the three major types SF envisions. The other two are when we go to their worlds to meet them and when they come to Earth to meet us (yes, there are other variants, but these three probably form the bulk of the literature). One thing we often see on Earth is that, when People A can travel to People B but People B can’t visit People A, an encounter between them is likely to produce more influence on and damage to People B than to People A. I’m hard pressed to think of an earthly example where distant folk met in the middle on equal terms. Had Portuguese caravels met Chinese junks on the Indian Ocean in the fifteenth century, that might have come close. But the timing didn’t quite work.

I’ll concentrate here on technologically advanced aliens coming to Earth, because that’s one of the things going on in my upcoming Three Miles Down. Stories where they just conquer us and incorporate us into their political structure are surprisingly rare. This has to be because we don’t like to imagine ourselves defeated–who would? John W. Campbell hardly ever bought that kind of story for Astounding/Analog for that very reason. I’ve done one myself, a novelette called “ opens in a new windowVilcabamba”. It takes its title from the town where the Incas kept their rump state for fifty years after the Spaniards overran most of their empire, and where they tried (and failed) to learn how to cope with the overwhelming invaders. Modern humans in my piece have similar problems with the alien Krolp.

Most of the time, though, writers who tackle the theme try to work around conquest. This has been true ever since the days of H.G. Wells and The War of the Worlds, when germs deal with the Martians even though humans can’t. A more recent, and deliciously improbable, take on the invading-aliens theme is Poul Anderson’s The High Crusade. An all-conquering starship lands in a medieval English village, and the locals capture it. One of the aliens then sends it back to his part of the galaxy, with the humans aboard. He’s certain that will finish them forever. Things don’t quite work out the way he hopes, though. It’s a story that will make you laugh your asteroids off.

I’ve worked around conquest by invading aliens a couple of times myself. Two of my stories, “Herbig-Haro” and “The Road Not Taken,” are set in a universe where faster-than-light travel is an easy discovery that shapes a race’s technology forever after–and that humans don’t happen to make. So when the aliens invade us (in “The Road Not Taken”), their spaceships land . . . and out they come, armed with matchlocks and black-powder cannon. We don’t have FTL, but we sure do have a lot of stuff they aren’t looking for. “Herbig-Haro,” on the other hand, is a meet-in-the-middle piece, with humans encountering another species that didn’t quickly find the hyperdrive but did develop electronics and nuclear weapons.

And I’ve written the Worldwar books. The Race sent a probe to Earth 800 years before, and the data it returned showed that humans would make an easy addition to the Empire: the most dangerous Earthly warriors rode animals, carried lances and swords, and wore chainmail for protection against the slings and arrows of outrageous enemies. So the Race, in its leisurely way, readied a conquest fleet and came to Earth . . . in May 1942, when World War II was about as perfectly balanced as it ever was. We turned out to be a little more advanced than they expected. Just a little.

The irony is that, in most historical periods, that 800-year delay wouldn’t have meant much. If the probe surveyed us in 3000 BC and the fleet arrived in 2200 BC–well, so what? Same deal if the probe came in 400 BC and the fleet followed in 400 AD. If the probe checked us in 650 AD and the fleet followed 800 years later, the Race might have been surprised at taking fire from early cannons, but it still would have mopped us up without breaking a sweat (not that the Race, being reptilian, sweats). But walkovers don’t make for interesting plots, so I chose to give us at least a fighting chance.

Which brings me, by easy stages, to Three Miles Down and its aliens. In real history, the Soviet sub K-129 sank north of Hawaii in 1968. We found it on the seabed; the Russians couldn’t. The CIA spent a moon landing’s worth of money building the Hughes Glomar Explorer to raise the sub and examine Soviet missiles and codebooks. In 1974, it . . . partially succeeded: the most interesting piece of the sub broke away as it was being raised.

In Three Miles Down, the K-129 sank because an alien ship already on the bottom of the Pacific sank it. Learning that made the recovery mission even more urgent and even more secret than it really was. Jerry Stieglitz, a grad student in oceanography, is aboard the Glomar Explorer mostly as cover. Life gets even more complicated than he expects. This is 1974. The Cold War and the Watergate investigation are in full swing. Adding beings from another planet could end the world–one way or another. Stay tuned!

Harry Turtledove (he/him) is an American fantasy and science fiction writer who Publishers Weekly has called the “Master of Alternate History.” He has received numerous awards and distinctions, including the Hugo Award for Best Novella, the HOMer Award for Short story, and the John Esthen Cook Award for Southern Fiction. Three Miles Down is our from Tor Books now.

Order Three Miles Down Here:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Do you love aliens in sci-fi? Are you fascinated by all the different ways extraterrestrial life can be brought to the pages of books? So does Harry Turtledove, author of

Do you love aliens in sci-fi? Are you fascinated by all the different ways extraterrestrial life can be brought to the pages of books? So does Harry Turtledove, author of