opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

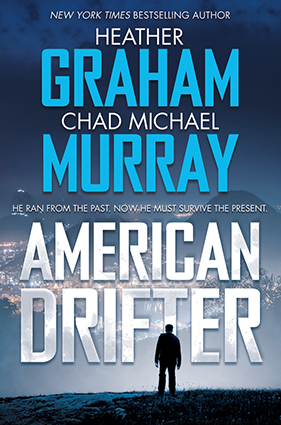

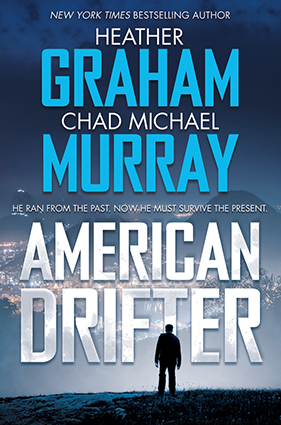

A young veteran of the US Army, River Roulet is struggling to shake the horrors of his past. War is behind him, but the memories remain. Desperate to distract himself from the images haunting him daily, River abandons the world he knows and flees to the country he’s always dreamed of visiting: Brazil.

Rio de Janeiro is everything he hoped for and more. In the lead-up to Carnaval, the city is alight with music, energy, and life. With a few friends at his side, River seems to be pulling his life together at last.

Then he meets the enchanting Natal, an impassioned journalist and free spirit—who lives with the gangster that rules much of Rio.

As their romance blossoms, River and Natal flee together into the interior of Brazil, where they are pursued by the sadistic drug lord, Tio Amato, and his men. When River is forced to kill one of those men, the chase becomes even deadlier. Not only is the powerful drug boss after them, the Brazilian government is on their trail as well.

Will the two lovers escape—and will River ever be free of the bloody memories that haunt him?

opens in a new windowAmerican Drifter will become available November 14th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

Chapter 1

River Roulet knew the strange whistling sound—it was far too familiar.

The sound heralded the arrival of a bomb.

His body instantly flinched as his natural instincts for survival set in.

The bomb fell. The earth shuddered and exploded into a violent storm of debris. Men screamed and missiles seemed to hurl around the dusty desert landscape.

The missiles were men—and body parts.

He felt himself breathe; he hadn’t been hit. His hearing was numbed and he was blinded for several seconds and then the debris began to clear.

He saw them—the woman and child—standing atop a small rise in the dry and brittle landscape far beyond the bombing. They were there . . . a distant blur in the distance, as the mist of dust and dirt began to clear. He struggled to stand, to warn them there was danger, but they were gone, and when he looked around, he was alone in a sea of death.

He let out a hoarse cry.

And he woke himself up from the nightmare that plagued him far too often.

There was no desert around him; the air was rich, his surroundings verdant with the foliage that grew in profusion on the outskirts of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

For a moment, he laid shaking, trembling. He took a deep breath, fighting the confusion that made it seem as if the mist from the imagined explosion had crept into his mind when he first awakened from the dream. War was behind him; he had come to Brazil to explore what was beautiful and different in nature, far from the past and far from memories of the past. Battle was over; he had let go of everything except that which he could carry on his back.

There was no regimen to be followed, there wasn’t anything he owed to anyone, and his days were now free; he’d vowed to forget the bombs and violence that had plagued the years gone by.

He’d had a glorious bath in the fountain—something he could manage because it was Brazil—and the morning stretched before him with a magnificent sun overhead, a touch of cool moisture in the air, and this new world to be explored.

For a moment, he felt a sharp pain in his head. The dream awakened memories; memories he didn’t want to have, memories he had come here to lose. They were there somewhere, he knew, at the far back of his mind, but if he pressed his temple between his thumb and forefingers, the threat that they would erupt in full subsided.

The past seemed to tease. It would return in the nightmares, but if he wakened, if he pressed the nightmares back, nothing bloomed into truth in his mind. He’d come here to bury the horrors that had gripped him, to begin anew.

He forced himself to feel the ripple of the breeze and hear the lilting, tinkling sound of the nearby stream as water danced over pebbles and rocks.

The pain faded.

He’d slept under the canopy of the jacaranda trees; the earth had been soft enough and it had been good to sleep in the open, but tonight, he’d head to the hostel owned and managed by Beluga, the massive African-Brazilian he could count as one of his few real friends in the Rio de Janeiro area. Beluga’s place was outside the city, surrounded by foliage and rich farmland. It was a beautiful place to sketch, and a pleasant place to stay.

He paused for a moment to take in the quiet. He loved Rio at any time of the year, and it was particularly hectic now that Carnaval grew near. The city felt supercharged. The horns blaring in the busy streets were enough to deafen. No matter—samba bands vied with them now at all hours of the day and night.

Being here right now, where the jungle retained a tenacious hold, he could hear the sound of the leaves rustling as birds swept by. It was a nice change.

Just as Beluga’s would be nice tonight.

River rose and stretched, shaking off the remnants of the dream. He paused for a minute and listened again to the sound of the jungle that encroached upon the city. As he looked up, a parrot took flight and soared over the trees; he wished he knew more about the birds and other creatures here, but he had time to learn. He had all the time in the world.

Rio de Janeiro was wonderful—one of the most wonderful cities on earth. On the one hand, it was massive, with a population of over six million of the world’s most diverse people—twelve million in the larger metropolitan area. While Portuguese was the primary language, people could be heard speaking any language known to man. They were black and white and every shade in between. River thought that was one of the things he loved most about Rio and Brazil—the diversity of people and the way that skin tones and backgrounds had become so multitudinous that only the very rich or incredibly snobby ever noticed any difference between white, brown, black, or red—or any color in between.

Two things were incredibly important in Brazil: samba and soccer. Not that there weren’t world-class museums and theaters and concert halls. But the people loved their soccer teams and their music. Samba schools were everywhere. And, at any time, when music could be heard through an open doorway, people might be seen dancing in the streets—practicing their newest moves.

And the streets were constantly filled with that music beneath the ethereal shade of the mountains, the blue skies, and the deeper blue seas. The city was magic and River loved it, from the beaches of Ipanema to the jungle forests that encroached upon the city.

This was Rio. While acceptance of just about anything was the general rule, it was still a country where there were the very rich; there were the very poor. It was true that money could matter; that the rich could consider themselves a bit more elite. But when Carnaval neared, there were the very rich everywhere, and the very poor everywhere, and it seemed that then, it didn’t matter so much. There were also the tourists—who did not know the bairros, or neighborhoods, of the city. There were big city buildings, skyscrapers that touched the clouds. And there were farmers on the outskirts still tilling their fields as if the land had never seen the arrival of big business. Rich tourists might go to many of the big balls, but even they knew that the Carnaval was really in the streets.

Carnaval had been celebrated in one or way another since the eighteenth century; first, it was taken from the Portuguese Festa de Entrada, or Shrovetide festivals—always a day to enjoy before the deep thought and abstinence of Lent. In later years, the Rio elite borrowed a page from the Venetian Carnavale and introduced elaborate balls. But the majority of the people were not the elite—they had their own festival in the street and it was funner, and soon, even those who were very rich wanted to play on the street, as well. The bands were magnificent: the samba was done on the walks and boulevards, and performers were everywhere.

There were so many wonders to be seen in Rio. But the greatest wonder of Rio was still to come, and one could feel the pulse of a city that was filled with natural beauty and joy. As in most cities, there were neighborhoods, and if you stayed, if you became part of the people, you knew the little fountains and the mysterious trails into the jungle and the special places where, in the midst of that twelve million people, you could be alone.

He was glad that he hadn’t come just for Carnaval. He had come to explore. To know and understand the people.

Reaching into his pack, he drew out his map of Brazil. He loved to study the map and read the guidebooks on the country. It was so huge and diverse and he intended to see a great deal of it, beyond Rio, at his leisure. Later, he’d talk to Beluga, and see what Beluga had to say about the wonders to be seen when he started out traveling again. He set his finger on the map, circling Rio de Janeiro and São Paolo, thinking that he might travel to the southwest. Or, perhaps, he’d head inland to see the wonders of Brasília, the planned city that now housed the federal capital. The country was massive; there were so many places he could go.

River gathered his belongings, shouldered his knapsack, and headed toward the sound of water. The picture that met his eyes was beautiful and peaceful; wildflowers grew haphazardly by water that glistened beneath the sun. The sound of children’s laughter drifted from downstream, closer to the city. He splashed cold water on his face, dug in his bag for his toothbrush, and cleaned up.

He was hungry. There was an open-air market just down the hill and he could find all kinds of delicious things to eat there.

The walk, he thought, was as beautiful as all else. He knew that a lot of Americans considered Brazil an exotic place—but one to visit, not a place to stay. It was true that here the middle class was slim; people tended to be very rich or very poor. But it cost nothing to look at the wild profusion of foliage and trees, breathe in the air, and feel the warmth of the sun.

There was a noise up ahead.

Without thinking, River paused. He didn’t know what made him refrain from moving forward, but some instinct kicked in.

Now a splash. On the road ahead where a little bridge crossed the river.

He moved off the path, climbing up the foliage-and tree-laden hill that rose next to the river to see what had given him chills. Carefully, he moved to a jagged crest and looked down.

There was a car on the bridge—a black car like the one that had approached the fountain the day before.

The trunk was open. River had the feeling that something had just been taken from it.

And thrown over the bridge.

Three men were out of the car, looking over the wall of the little cement bridge.

They were all big, muscled, and wearing almost identical blue jackets. All looked to be somewhere in their late thirties or forties, dark-haired, heavy-set.

Paid thugs?

From his vantage point, River could see the water—but not what had been thrown into it. The river was fast-moving, churning in little white waves and bursts.

It seemed the men were looking at something, or for something—and that they were satisfied by what they saw.

A fourth man rose from the backseat of the car; he was about six feet tall with dark wavy hair and a lean, muscled build, dressed in a suit that even at a distance appeared to be designer apparel. He looked strong, impressive, even; but when he turned slightly, River felt there was something in his face that kept him from being attractive when he should have been very handsome with his dark hair and well-honed physique. There was a twist to his mouth and hardness in his eyes. It seemed like cruelty was stamped into his features.

Tio Amato? he wondered.

The drug lord who ruled much of the city?

He’d never met the man and looks could be deceiving, he knew.

The three thugs approached what appeared to be their leader and spoke in hushed tones that River couldn’t begin to hear. Then they returned to the car, which promptly revved into gear and continued over the bridge.

Carefully, River shuffled back down the hillside and walked to the bridge, to the point where the men had looked over the water. He saw nothing. Nothing but water, white-tipped as it rushed over stones, beautiful beneath the sunlight.

He stepped back, still puzzled, still uneasy. His eyes flickered to where his hands had touched the concrete wall.

There was something there. Tiny droplets of liquid, in a burned crimson color.

Blood?

He didn’t touch it, but he stared at it. He felt something curling inside him.

Was it blood? Could the man who considered himself lord of Rio kill—and dispose of bodies in such a manner?

He debated telling the police what he had seen. But he was an American. For all he knew, the police could be on Tio Amato’s payroll as well. Furthermore, he wasn’t sure what he could really say. These men were on the bridge. I think there are blood spots there now?

Had he seen the man kill anyone? Had he seen a body?

No, and no.

He stood still for a moment, debating.

Maybe someone as bad—or worse—had been killed.

No, that was rationalizing a lack of action.

But would he be believed by the authorities—or by anyone—if he tried to tell them what he had seen?

And even if he was believed, would it matter?

He had no proof. There was no one else here. He had no video. Nothing.

After a moment, he decided that he would tell Beluga what he had seen; Beluga had been born here and never gone far. He’d know the lay of the land.

Beluga would know what to do.

Copyright © 2017 by Heather Graham and Chad Michael Murray

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

A Shattered Circle is a legal thriller that’s anything but boring. NYC judge William Lonergan becomes mentally-impaired after an accident. His wife, who doubles as his secretary, preserves Lonergan’s career by covering up his condition — but she can only do it for so long. After Lonergan gets attacked, he and his wife move to their summer house for safety… a big mistake.

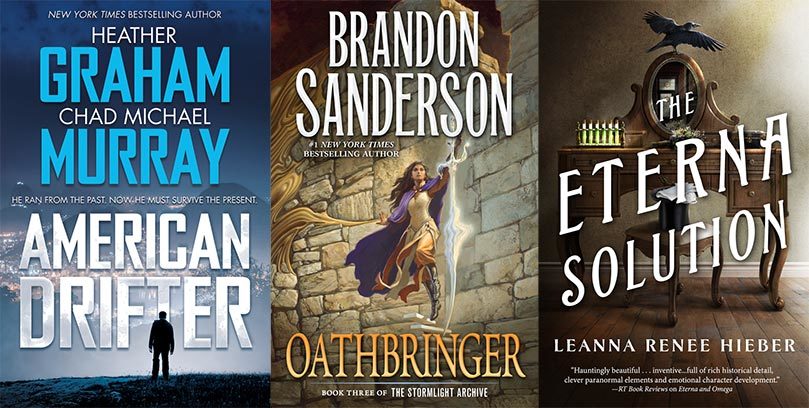

A Shattered Circle is a legal thriller that’s anything but boring. NYC judge William Lonergan becomes mentally-impaired after an accident. His wife, who doubles as his secretary, preserves Lonergan’s career by covering up his condition — but she can only do it for so long. After Lonergan gets attacked, he and his wife move to their summer house for safety… a big mistake. Young vet River Roulet tries to escape his PTSD by moving to Brazil. He falls in love with journalist Natal who lives with the top drug lord of Rio, Tio Amato. River and Natal try to escape to the interior of Brazil, but Tio is after them. A psychological thriller as much as an action-packed one, American Drifter is an expected delight from bestselling author Heather Graham and famous celeb Chad Michael Murray!

Young vet River Roulet tries to escape his PTSD by moving to Brazil. He falls in love with journalist Natal who lives with the top drug lord of Rio, Tio Amato. River and Natal try to escape to the interior of Brazil, but Tio is after them. A psychological thriller as much as an action-packed one, American Drifter is an expected delight from bestselling author Heather Graham and famous celeb Chad Michael Murray! Terrifyingly plausible, And Into the Fire follows journalist Jules Meredith and head of the CIA’s Pakistan desk Elena Moreno as they fight the clock to stop ISIS from dropping three Pakistani nukes on U.S. soil. This is no easy feat when the corrupt American president and a Saudi ambassador both want the two women killed. Realistic, character-driven, and fine-tuned, And Into the Fire is sure to get your heart racing!

Terrifyingly plausible, And Into the Fire follows journalist Jules Meredith and head of the CIA’s Pakistan desk Elena Moreno as they fight the clock to stop ISIS from dropping three Pakistani nukes on U.S. soil. This is no easy feat when the corrupt American president and a Saudi ambassador both want the two women killed. Realistic, character-driven, and fine-tuned, And Into the Fire is sure to get your heart racing! The breathtaking sequel to The Sixth Station, Book of Judas is original and a serious must-read. Stasi intertwines religion and history to create a suspenseful, high-stakes thriller. NYC reporter Alessandra Russo must save her kidnapped son by finding the last missing pages of the Book of Judas — pages that contain a secret that could upend Christianity in its entirety.

The breathtaking sequel to The Sixth Station, Book of Judas is original and a serious must-read. Stasi intertwines religion and history to create a suspenseful, high-stakes thriller. NYC reporter Alessandra Russo must save her kidnapped son by finding the last missing pages of the Book of Judas — pages that contain a secret that could upend Christianity in its entirety. Based on the premise that a dangerous weapon has the power to destroy the United States in a single moment, One Second After looks at a small town’s response to an electromagnetic pulse attack on America. The country is thrown back to a time of chaos and the darkness of the past (literally – no electricity), forcing retired U.S. Army Colonel John Matherson to mobilize. This novel is so legit that Congress praised it for its realism and called it a book that all Americans should read (!).

Based on the premise that a dangerous weapon has the power to destroy the United States in a single moment, One Second After looks at a small town’s response to an electromagnetic pulse attack on America. The country is thrown back to a time of chaos and the darkness of the past (literally – no electricity), forcing retired U.S. Army Colonel John Matherson to mobilize. This novel is so legit that Congress praised it for its realism and called it a book that all Americans should read (!). Coast Guard rescue swimmer Trey DeBolt is in a tragic helicopter accident off the coast of Alaska. When he wakes up, he finds himself in Maine, cared for by a lone nurse. The world thinks Trey is dead… and someone wants to keep it that way. When his nurse is assassinated, Trey is forced to run for his life. Along the way, he discovers that he is deeply entrenched in a top-secret government project that has left him with a tremendous super power. Cutting Edge is a suspenseful mystery thriller that will keep you on your toes!

Coast Guard rescue swimmer Trey DeBolt is in a tragic helicopter accident off the coast of Alaska. When he wakes up, he finds himself in Maine, cared for by a lone nurse. The world thinks Trey is dead… and someone wants to keep it that way. When his nurse is assassinated, Trey is forced to run for his life. Along the way, he discovers that he is deeply entrenched in a top-secret government project that has left him with a tremendous super power. Cutting Edge is a suspenseful mystery thriller that will keep you on your toes! Eric Van Lustbader is the bestselling author of the Bourne series, and The Fallen does not disappoint: it’s a pulse-pounding thriller that explores religion, politics, and good and evil. The Testament of Lucifer has been discovered in a remote cave — and has the possibility to unleash chaos and evil all over the world. Can it be stopped? We know the answer, but you’ll have to read to find out!

Eric Van Lustbader is the bestselling author of the Bourne series, and The Fallen does not disappoint: it’s a pulse-pounding thriller that explores religion, politics, and good and evil. The Testament of Lucifer has been discovered in a remote cave — and has the possibility to unleash chaos and evil all over the world. Can it be stopped? We know the answer, but you’ll have to read to find out! Part of the Kirk McGarvey series, End Game throws you right into the heart of a serial killer case… occurring in the CIA headquarters. McGarvey, former CIA assassin, must find the killer — but first he must understand the motive, which traces back to something buried in the foothills of Iraq: something that could unleash an apocalyptic war in the Middle East. Oozing with action and suspense, you’ll love this thriller.

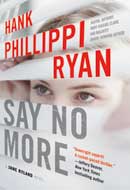

Part of the Kirk McGarvey series, End Game throws you right into the heart of a serial killer case… occurring in the CIA headquarters. McGarvey, former CIA assassin, must find the killer — but first he must understand the motive, which traces back to something buried in the foothills of Iraq: something that could unleash an apocalyptic war in the Middle East. Oozing with action and suspense, you’ll love this thriller. Boston reporter Jane Ryland reports a hit-and-run, destroying someone’s alibi. Her homicide detective fiancee Jake Brogan is searching for the killer of a famous Hollywood screenwriter. Meanwhile, Jane helps a date-rape victim tell her story, causing her to receive a threatening message: SAY NO MORE. The multiple plot lines seamlessly stream together in this unpredictable, complex, and relevant thriller.

Boston reporter Jane Ryland reports a hit-and-run, destroying someone’s alibi. Her homicide detective fiancee Jake Brogan is searching for the killer of a famous Hollywood screenwriter. Meanwhile, Jane helps a date-rape victim tell her story, causing her to receive a threatening message: SAY NO MORE. The multiple plot lines seamlessly stream together in this unpredictable, complex, and relevant thriller.