opens in a new window

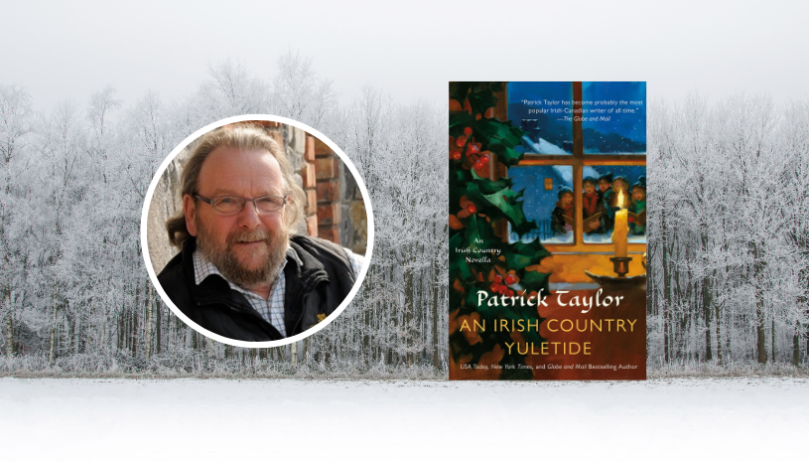

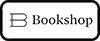

A charming Christmas entry in Patrick Taylor’s beloved internationally bestselling Irish Country series, An Irish Country Yuletide.

December 1965. ‘Tis the season once again in the cozy Irish village of Ballybucklebo, which means that Doctor Fingal Flahertie O’Reilly, his young colleague Barry Laverty, and their assorted friends, neighbors, and patients are enjoying all their favorite holiday traditions: caroling, trimming the tree, finding the perfect gifts for their near and dear ones, and anticipating a proper Yuletide feast complete with roast turkey and chestnut stuffing. There’s even the promise of snow in the air, raising the prospect of a white Christmas.

Not that trouble has entirely taken a holiday as the season brings its fair share of challenges as well, including a black-sheep brother hoping to reconcile with his estranged family before it’s too late, a worrisome outbreak of chickenpox, and a sick little girl whose faith in Christmas is in danger of being crushed in the worst way.

As roaring fireplaces combat the brisk December chill, it’s up to O’Reilly to play Santa, both literally and figuratively, to make sure that Ballybucklebo has a Christmas it will never forget!

opens in a new windowAn Irish Country Yuletide will be available on October 12th, 2021. Please enjoy the following excerpt!

Doctor Fingal Flahertie O’Reilly tried to stifle a distinctly satisfied burp as he finished the last trace of his housekeeper’s sherry trifle. “Sorry, Kitty,” he said to his wife of nearly six months.

“You are forgiven.” She smiled at him, and the sparkle in her grey-flecked-with-amber eyes, as always, made him tingle. Had done so ever since he’d met her as a student nurse in Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital in Dublin in 1934. They’d parted in 1936, he to pursue his, to him, all-important career, she to Tenerife in the Canary Islands to care for orphans of the Spanish Civil War.

Until last summer, he hadn’t seen her since, but he’d carried an ember for the student nurse from Tallaght, Dublin, all his life. Even during his short marriage in 1940. That ember had woken and burst into flame when he, a widower for twenty-four years, had discovered she was working in Belfast’s Royal Victoria Hospital as a senior nursing sister in the neurosurgical operating theatre.

Kitty leant to one side, stretched her right arm down, and straightened up holding something tied with a red ribbon.

“Seeing Christmas Day will be here soon, I’ve brought you an early present.”

“What are they?” he said, eying what he now saw was a bundle of envelopes.

“I’m still unpacking a few boxes from my Belfast flat and this morning I found these and thought you might enjoy reading them today.”

“Why today?”

She smiled. “Because it’s special. Our first Christmas as man and wife.” She blew him a kiss.

The door to the dining room opened and Mrs. Kincaid, or “Kinky,” as she was known, his housekeeper of nineteen years, entered carrying a tray with a steaming pot of coffee and an open box of Rowntree’s After Eight dark chocolate mint cremes.

“Kinky, you have excelled yourself,” O’Reilly said. “Prawn cocktail, roast leg of lamb with mint sauce, potatoes roasted in goose fat, broad beans, and carrots? You are a culinary genius.” She chuckled, making her silver chignon and three chins shake. “Sure, wasn’t it only a shmall-little thing, so,” she said in her offhand way, but he could tell she was pleased with the praise. “I see you’ve eaten up however little much was in it.” Her Cork accent was gentle on O’Reilly’s ear.

“It’s nothing less than you deserve, Doctor, and you, Mrs. O’Reilly. You work very hard the pair of you, helping other people, day in, day out. You deserve good food when you come home, so. Now, here does be your coffee and After Eights.” She set the tray on the table, unloaded its contents, and cleared away the dirty plates. “I know you’re expecting the marquis in a few minutes, so when he arrives, I’ll take him up to the lounge and bring the coffee and mints up once you’re all settled.” She fixed O’Reilly with a steely gaze. “Do not, sir. Do not eat all of them.”

O’Reilly cringed just a little at his housekeeper’s no-nonsense tone. “I promise.” Those citizens of Ballybucklebo who knew their middle-aged medical advisor as gruff and taciturn would have been amazed by his humility. But she’d always had that effect on him whenever she admonished him. He’d met Kinky here in this very house in 1938, just before he’d gone off to the war, and had returned here to buy the practice in 1946.

The housekeeper left, closing the door behind her. As she went, a sudden gust hurled rain against the room’s bow window making a noise like a badly uncoordinated kettle drummer.

“Glad we’re in here tonight,” O’Reilly said. “Heaven help the sailors. That’s a powerful wind.” He shook his head, offered Kitty a mint chocolate, and helped himself to two wrapped in their open-ended paper envelopes. “Speaking of power, as her fellow Cork folk would say, ‘That Maureen “Kinky” Kincaid is a powerful woman, so.’” He bit into a bittersweet mint. Perfection. “I’d have been lost without her these nineteen years. Back then for her sake I’d hoped she might remarry, but for my own, I don’t know what I’d have done without her. Now with you here, love, I’m not a domestically useless old bachelor anymore, and when she told us she was getting married again, I couldn’t have been more delighted. I suppose I’m selfish, but I’m very glad she stayed on with me for as long as she did.”

“You? Selfish, old bear?” Kitty finished her mint. “I know you too well. It’s all part of the—put that third mint down, Fingal.”

He set it back in the box.

“Do you remember that 1950s song, ‘The Great Pretender’?”

“Yes. The Platters wasn’t it, 1955?”

She nodded. “That’s you in a nutshell. Stiff upper lip. Terrified of letting your feelings show.”

“Well. I, that is. I mean . . .” But it was true. He often felt things deeply inside but had great difficulty saying the words aloud.

“Rubbish.” She smiled to show there was no anger in her, picked up her early gift, and handed it to him. “And I’ve got proof of your feelings in writing. Have a read of some of these.” He accepted the bundle and recognised his own straggling scrawl on the top envelope: Miss Kitty O’Hallorhan, 10A, Wellington Park, Belfast. His breath caught. She’d kept the letters he’d written to her after they’d met again in August 1964. Too scared of being rejected face-to-face, he’d taken to expressing his true feelings in letters. He inhaled deeply. “You kept them, even after we were married?”

She blew him a kiss. “Of course, I did. Some of them are very sweet, Fingal. You were and still are a very romantic man, and I love you.”

He rose, leaving the bundle on the table and intending to give her a kiss, but the front doorbell rang.

“That’ll be the marquis. Let’s greet him.” Kitty rose and as they left the room, she sang out. “We’re answering the door, Kinky.”

Lord John MacNeill stood on the step of Number One Main, Ballybucklebo, his camelhair coat sodden, his trilby hat dripping with rain, looking very much like a man in need of a friend. He and O’Reilly had got to know each other years ago through their shared interest in the game of rugby and the Ballybucklebo Bonnaughts Sports Club.

“Come in out of that, John. I’m sure the geese are flying backward.”

“Thanks, Fingal.” John MacNeill came in from the howling gale and shut the door behind him. “Hello, Kitty.”

“Hello, John. My goodness, you look wet through.”

Kinky, who had always had a soft spot for the marquis, had come to the door anyway. Now she curtseyed, and said, “Let me take your hat and coat, sir. The wires must be shaking out there, so.”

“It is a dirty night.” He handed her his sopping coat and hat, revealing a head of neatly brushed iron-grey hair.

“I’ll take these through to my kitchen,” she said, “and put them to dry in front of the range then I’ll bring up the coffee.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Kincaid. That is very kind.” She made another curtsey and left.

“Come up to the fire, John,” O’Reilly said. “You must be foundered.”

“Mmm.” He rubbed his hands together. “Trifle nippy. Please lead on.”

As they crossed the first landing, the marquis nodded to the photograph of O’Reilly’s old battleship, HMS Warspite. “Saw the Times yesterday. Historical piece. I didn’t know, but seems they finished scrapping her in 1957.”

“She ran aground ten years before in Prussia Cove, Cornwall, on her way to the breaker’s yard.” O’Reilly laughed. “The grand old lady always did have a mind of her own.” He and Kitty stood aside to let John MacNeill precede them into the cosy upstairs lounge where the curtains were closed over the bay windows and a coal fire burned in the grate. There, presumably under some kind of truce, O’Reilly’s white cat Lady Macbeth lay curled up beside his black Labrador, Arthur Guinness.

Her ladyship ignored them. Arthur opened one brown eye, smiled at the newcomer, and thumped his tail down—once.

“Have a pew, John.” O’Reilly indicated a semicircle of four armchairs arranged around the fire.

Kitty took a chair and John sat beside her, crossing his legs and hitching up his flannel trouser leg to protect the crease.

Kinky appeared and set the coffee and mints on a table beside the fire as O’Reilly stood by the sideboard. “Thanks, Kinky,” he said as she left. “My love?”

“Have we some Taylor’s port still?” O’Reilly nodded. “John?”

“Same as you, Fingal, as always.”

In moments Kitty had her port, the men their neat John Jameson Irish whiskey, and O’Reilly had seated himself beside John MacNeill. “Cheers.”

“Cheers.” They drank.

“So, John. You sounded a bit—well—not entirely yourself on the phone. What can we do?”

John MacNeill stared at the carpet for what seemed like ages until he raised his head and looked O’Reilly in the eye. “It’s my brother in Australia.”

O’Reilly choked on his whiskey, coughing and spluttering, “Brother? What brother? John, I didn’t know you had a brother. How could I not know?”

John’s smile was wry. “Not many people do, and the rest of the family would be quite happy if no one did. Father was adamant that people not speak of Andrew and it’s a measure of how much my father was respected—or feared—that no one did.”

O’Reilly leant forward in his seat, ignoring his whiskey. “Why ever not?”

John sipped his drink. “Andrew MacNeill was only two years younger than me, but in some ways, he was younger than that. I took him under my wing when we were children. Especially for the three years we were at Harrow together. MacNeill major and MacNeill minor they called us. I protected him from the inevitable bullying. Kept an eye on him as long as I could. He was sixteen when I left Harrow in 1919. I didn’t learn until after he’d been sent down from Cambridge in 1925 with a rowing blue, but no degree, that he had become a complete scoundrel. The usual culprits I’m afraid—drinking, gambling, a rather racy taste in women. By then, I was within weeks of finishing at Sandhurst officer’s training school.”

O’Reilly shook his head.

John set his glass on the table. “Then, in mid-1926, Andrew was expelled from White’s club in Piccadilly.” He glanced up and saw Kitty’s questioning look.

“It’s the oldest gentlemen’s club in London. Founded in 1693. Very exclusive. Very proper. Very.”

There was a short silence until O’Reilly said, “This must be difficult for you to talk about, John. Take your time.”

“Thank you, Fingal.” He uncrossed and recrossed his legs. “I tried to help him. He was my little brother and I loved him. But he wouldn’t accept my help. Would never be serious long enough to discuss anything. I never found out why he was thrown out of White’s. Father refused to talk about it. He was a reasonably patient man, my father. He’d survived the shame of Andrew being sent down. Willing to let a young man go through a bit of a wild period. But the business at White’s, well, it was the last straw for the old man. So, Father paid off Andrew’s gambling debts and settled an out-of-wedlock paternity suit.” The marquis shook his head.

O’Reilly said, “And you probably still feel guilty about not being able to help him.”

“I do.” John nodded. “I know, Fingal, you’ve read Somerset Maugham’s pre-war South Pacific short stories. I’ve seen them sitting in this very room. One of his stock characters was the upper-class waster who was provided with a monthly stipend remitted to a local bank in one of the distant colonies on condition he never came home. The remittance man.

“Andrew was one. Father packed him off to Australia, gave him a monthly allowance sent to a bank in Perth, and told my brother never to show his face in Ireland again.”

“How awful. For both of you,” Kitty said.

John grimaced. “It was. I missed Andrew, but the war kept me occupied for some time. I stayed in the Guards until 1951, then I had to come back to run the estate after Father’s death.”

“Of course.”

“I thought we’d never hear from Andrew again, but I got a letter in June of ’51 shortly after Father’s death.”

O’Reilly thought immediately of his letters sitting in the dining room, but he turned his attention back to John MacNeill. “The letter, sending his condolences for Father’s death and asking me to cancel his allowance, contained a clipping from the County Down Spectator about the Ballybucklebo Bonnaughts seeking donations to improve their clubhouse. Someone here must have stayed in touch with him and sent him the paper. In the letter, Andrew claimed to have made a great deal of money in gold mining and asked for the privilege of meeting half the costs of the clubhouse renovations. Anonymously, of course. There was only a PO box address from a place called Kalgoorlie in Western Australia.”

“Good gracious. So, he was still in Australia twenty-five years later,” Kitty said.

“He was. And a rich man.”

O’Reilly asked, “And was the promise honoured?”

“After some back and forth correspondence, indeed it was. Although I made it clear this was an anonymous donation, I’m afraid most people at the time suspected my father was their benefactor, and I couldn’t correct them.”

“I certainly thought it was your father,” said Fingal.

“I wrote Andrew a number of personal letters in care of the address in Kalgoorlie asking him to come home, but never received any reply. Indeed, those letters about the clubhouse were the last we’d heard until two days ago.” He sat back in his chair and picked up his glass but didn’t drink.

Lady Macbeth stood, arched her back, then trotted to Kitty, jumped up onto her lap, and began dough-punching, alternately pushing and withdrawing one front paw then the other against Kitty’s thighs.

She stroked the little cat, whose purrs rumbled gently, and looked at O’Reilly. He wanted to jump into the conversation, to ask outright what had happened next. But one look at John told him the man had to tell this in his own time. So, O’Reilly diverted himself by sipping his whiskey, taking a long deep breath, and listening to the rattle of the rain on the window.

“Two days ago, I got a long-distance call from someone purporting to be Andrew and I’m damn sure it was. I’d know that voice anywhere. Said he was ill, that he’d booked flights to Heathrow arriving on Thursday the sixteenth. He’ll overnight there, fly to Aldergrove, and arrive in Ulster on Friday the seventeenth. He wants to see his old home one more time, he said, and wondered if he might also be able to see the clubhouse.”

“One more time,” O’Reilly said.

“Yes, that’s how he put it. It doesn’t sound good, I’m afraid. I fear the worst.” John ran a hand through his hair and looked down to the ground.

“And of course, you said yes, John?” Kitty spoke gently. “Naturally. He can stay with Myrna and me at the house.” O’Reilly watched as John again raked a hand through his hair.

“You know how strong-willed my sister can be. She had very little empathy for him then. I hope she will have more now.” He paused. “I’ll hire a private nurse if he needs one. But perhaps, if he’s well enough . . .” He paused and cleared his throat. “Perhaps I can put on a little thank-you for him at the club.” He shrugged, raising his hands palms up. “What do you think, Fingal?”

O’Reilly frowned. “I’ll come and see him on Sunday. I know he’ll be jet-lagged, but if he’s fit enough, why not bring him to the club’s annual Christmas party on Wednesday the twenty-second. Let the rest of the executive know in advance, of course, and simply introduce him to the folks in attendance? If that would be all right with your brother?”

John frowned, stroked his chin, then smiled. “I think that would be a splendid idea. Andrew’s always loved a party from the time he was a small child. But he’s not under the National Health Service, so send me a bill.”

O’Reilly snorted. “Send you a bill? To do a friend’s long-lost brother a small favour?” He shook his head. “In the words of one of the locals, ‘My esteemed gracious lord—away off and chase yourself.’”

John MacNeill smiled. “Thanks, to you both, for listening and thank you, Fingal, for your sage advice. I will be happy to accept your offer of your medical services and I’ll have a word with the rest of the executive so Andrew will be welcomed properly.” He finished his whiskey, refused a second, rose, and said, “Now I must be trotting along.”

“I’ll see you out,” O’Reilly said, “and I’ll be a minute or two, Kitty. There’s something I’d like to read downstairs.”

“Good night, John. It’s lovely to see you and I do so hope your brother’s illness isn’t serious. Please say hello to Myrna.”

“Thank you, Kitty. And I will.”

“And, Fingal . . .” She smiled, and her right eyebrow rose in that enticingly provocative gesture he had always loved. “Take all the time you need with your reading. I’ve got Lady Macbeth for company and my The Spy Who Came in from the Cold to finish.”

Having shown John MacNeill out into the gale, O’Reilly closed the front door and locked it. Good God, O’Reilly thought. John MacNeill and he had been close friends since 1946. And as John and Myrna’s medical advisor, O’Reilly had thought he knew just about everything there was to know about the MacNeill family. It certainly was going to take some unravelling— but then Fingal O’Reilly had always enjoyed mysteries.

In moments he was at the dining room table holding the bundle of letters, undoing their red ribbon, and riffling through them. He soon established by the postmarks that they were in chronological order, so, he thought, in the words of Julie Andrews in this year’s film The Sound of Music, “Let’s start at the very beginning.”

He opened the first envelope, drew out three pages of notepaper, and began to read. He noted he’d dated it September 12, 1964.

Dear Kitty,

I had great difficulty believing it in August when Barry told me a Sister Caitlin O’Hallorhan was working in the Royal and wished to be remembered to me. Remembered? Since I let you go in 1936, I have never forgotten you and to see you last night, hear your voice, kiss you good night, filled my soul.

He’d tried to tell her then, but the words simply had not come until he had sat at his desk and penned these words the next day.

Today I took Arthur Guinness for a walk and on our way, I saw a familiar tree. A Japanese maple. It is a delicate tree with lissome boughs and multi-fingered leaves. I care deeply for that little tree.

I love its annual cycle and think of it as a reflecting glass for my own feelings.

In the winter the tree is dormant, its bony fingers knobbed with knuckles. It’s a time of sleeping, when all creation turns into itself, and the world passes by unheeded, simply to be lived through until spring.

In my spring I met you, a golden girl.

Fingal had to stop reading and blow his nose.

We fell in love, a love so gentle, so fumbling and inchoate we hardly understood it. It was a love that, like the maple’s buds, swelled, burst, and flourished—and might have been consummated but for a sudden late frost. My love, like a frozen leaf, lay curled on the unforgiving ground.

The dead leaf cannot know that the tree survives. I didn’t know you held within you the tiny buds of our love, which you would nourish and keep alive to await a new spring.

What tells the maple buds to grow once winter has passed? I do not know what kismet put me face-to-face with you last month. I do know that meeting made my love grow again. I tried to blight it, to tell it I was snow-blind. But I could no more stop loving you than the tree could stop its spring growth.

After ripening, buds must burst. When I kissed you last night, I felt myself stretched by the burgeoning growth within. When you took your courage and told me you still loved me, my own love, which had stayed quietly curled in on itself, shook loose and, like a new leaf, opened and smiled at the sun.

But this mature, full-blooded love is far from the simple green love of the past.

The ripe leaves of my maple today are full, and their weight bends the boughs. They are red, somewhere between copper and maroon, a colour that would take the skills of a painter in oils to capture, and with more accuracy than these poor words of a physician. Their beauty stops my breath in my throat just like the beauty of our love holds a warm hand round my heart.

Before long they will start to fall to make a carpet of fire, but their deaths will not be the death of my tree. My tree will bide and hold its secret into itself, ready when the time comes to flourish again in spring sun. Then its leaves will burst forth as will my love . . . now and forever.

Your loving Fingal

Fingal blew his nose again, folded the pages, slipped the letter into the envelope, and put it to the bottom of the pile.

He stood slowly, walked across to his surgery, and put the bundle into the one drawer of the old roll-top desk he kept locked. He’d savour his thoughts about the rest, which he would read at his leisure.

He glanced up and grinned. Now he’d go upstairs, kiss his golden girl, and tell her how much he loved her.

Copyright © 2021 by Ballybucklebo Stories Corp.

Pre-order a Copy of An Irish Country Yuletide—available October 12th!

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

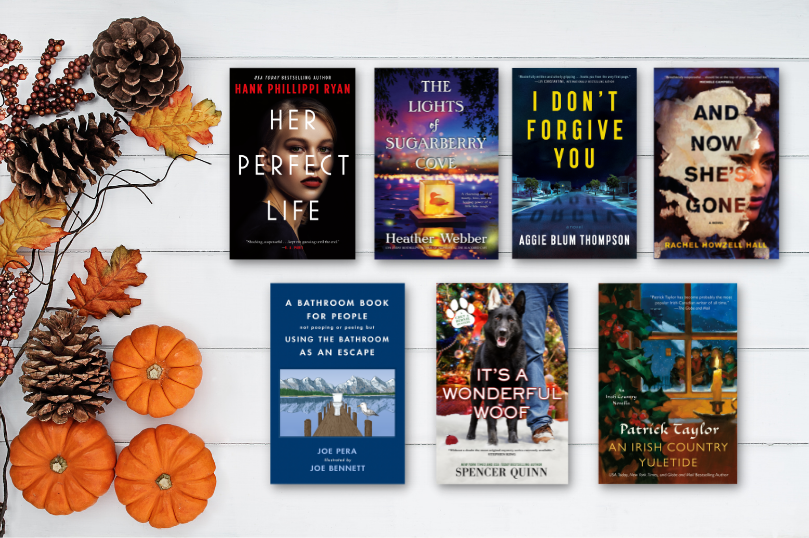

Nothing says “happy holidays” more than An Irish Country Yuletide by Patrick Taylor, which will give you all the cozy vibes as you read this while curled up next to the fireplace!

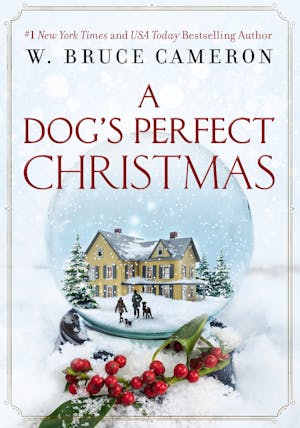

Nothing says “happy holidays” more than An Irish Country Yuletide by Patrick Taylor, which will give you all the cozy vibes as you read this while curled up next to the fireplace! If you’re a Hallmark Christmas movie lover during this time of year, then we think that A Dog’s Perfect Christmas by W. Bruce Cameron is nothing short of a perfect pick for you!

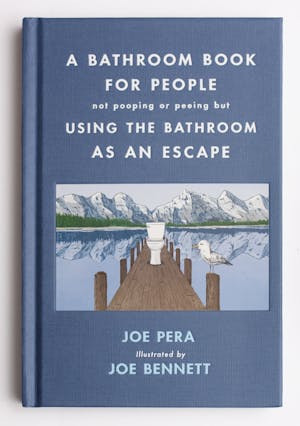

If you’re a Hallmark Christmas movie lover during this time of year, then we think that A Dog’s Perfect Christmas by W. Bruce Cameron is nothing short of a perfect pick for you! While this book isn’t specifically holiday-themed, it is absolutely perfect for helping you get through the stress that comes along with holiday-prepping…and perhaps seeing relatives at the dinner table that aren’t quite your favorite people.

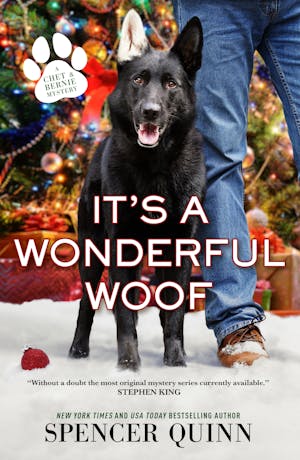

While this book isn’t specifically holiday-themed, it is absolutely perfect for helping you get through the stress that comes along with holiday-prepping…and perhaps seeing relatives at the dinner table that aren’t quite your favorite people. Suspense, a holiday adventure, buried secrets, and the most lovable dog sidekick all wrapped up in one story with a bow on top? Count us in!

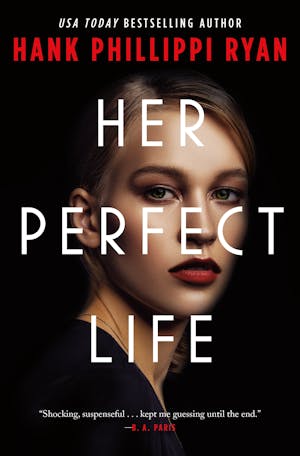

Suspense, a holiday adventure, buried secrets, and the most lovable dog sidekick all wrapped up in one story with a bow on top? Count us in! Are you someone who would rather skip traditional holiday books and instead read thrillers all year round, even after Halloween has come and gone? If so, then look no further than Her Perfect Life by Hank Phillippi Ryan.

Are you someone who would rather skip traditional holiday books and instead read thrillers all year round, even after Halloween has come and gone? If so, then look no further than Her Perfect Life by Hank Phillippi Ryan.