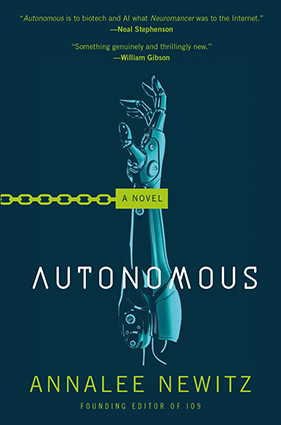

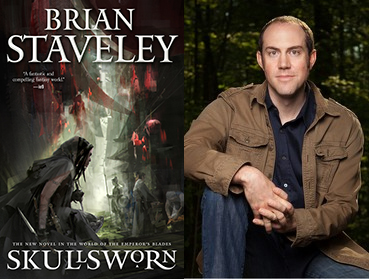

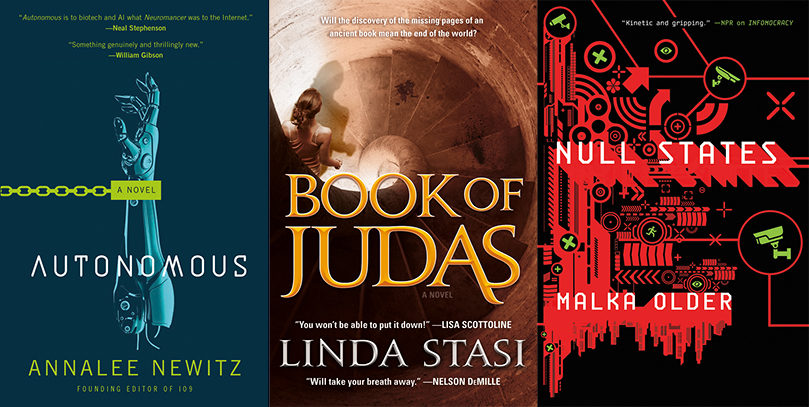

“Autonomous is to biotech and AI what Neuromancer was to the Internet.”—Neal Stephenson

“Autonomous is to biotech and AI what Neuromancer was to the Internet.”—Neal Stephenson

Earth, 2144. Jack is an anti-patent scientist turned drug pirate, traversing the world in a submarine as a pharmaceutical Robin Hood, fabricating cheap scrips for poor people who can’t otherwise afford them. But her latest drug hack has left a trail of lethal overdoses as people become addicted to their work, doing repetitive tasks until they become unsafe or insane.

Hot on her trail, an unlikely pair: Eliasz, a brooding military agent, and his robotic partner, Paladin. As they race to stop information about the sinister origins of Jack’s drug from getting out, they begin to form an uncommonly close bond that neither of them fully understand.

And underlying it all is one fundamental question: Is freedom possible in a culture where everything, even people, can be owned?

Please enjoy this excerpt from Annalee Newitz’s science fiction debut Autonomous.

One: Pirate Ship

June 25, 2144

The student wouldn’t stop doing her homework, and it was going to kill her. Even after the doctors shot her up with tranquilizers, she bunched into a sitting position, fingers curled around an absent keyboard, typing and typing. Anti-obsessives had no effect. Tinkering with her serotonin levels did nothing, and the problem didn’t seem to be dissociation or hallucination. The student was perfectly coherent. She just wouldn’t stop reimplementing operating system features for her programming class. The only thing keeping her alive was a feeding tube the docs had managed to force up her nose while she was in restraints.

Her parents were outraged. They were from a good neighborhood in Calgary, and had always given their daughter access to the very best pharma money could buy. How could anything be going wrong with her mind?

The doctors told reporters that this case had all the hallmarks of drug abuse. The homework fiend’s brain showed a perfect addiction pattern. The pleasure-reward loop, shuttling neurotransmitters between the midbrain and cerebral cortex, was on fire. This chemical configuration was remarkable because her brain looked like she’d been addicted to homework for years. It was completely wired for this specific reward, with dopamine receptors showing patterns that normally emerged only after years of addiction. But the student’s family and friends insisted she’d never had this problem until a few weeks ago.

It was the perfect subject for a viral nugget in the medical mystery slot of the All Wonders feed. But now the story was so popular that it was popping up on the top news modules, too.

Jack Chen unstuck the goggles from her face and squeezed the deactivated lenses into the front pocket of her coveralls. She’d been working in the sun’s glare for so long that pale rings circled her dark brown eyes. It was a farmer’s tan, like the one on her father’s face after a long day wearing goggles in the canola fields, watching tiny yellow flowers emit streams of environmental data. Probably, Jack reflected, the same farmer’s tan had afflicted every Chen for generations. It went back to the days when her great-great-grandparents came across the Pacific from Shenzhen and bought an agricultural franchise in the prairies outside Saskatoon. No matter how far she was from home, some things did not change.

But some things did. Jack sat cross-legged in the middle of the Arctic Sea, balanced on the gently curving, uncanny invisibility of her submarine’s hull. From a few hundred kilometers above the surface, where satellites roamed, the sub’s negative refractive index would bend light until Jack seemed to float incongruously atop the waves. Spread next to her in the bright water was an undulating sheet of nonreflective solar panels. Jack made a crumpling gesture with her hand and the solar array swarmed back into its dock, disappearing beneath a panel in the hull.

The sub’s batteries were charged, her network traffic was hidden in a blur of legitimate data, and she had a hold full of drugs. It was time to dive.

Opening the hatch, Jack banged down the ladder to the control room. A dull green glow emerged in streaks on the walls as bacterial colonies awoke to illuminate her way. Jack came to a stop beneath a coil of ceiling ducts. A command line window materialized helpfully at eye level, its photons organized into the shape of a screen by thousands of projectors circulating in the air. With a swipe, she pulled up the navigation system and altered her heading to avoid the heavily trafficked shipping lanes. Her destination was on a relatively quiet stretch of the Arctic coast, beyond the Beaufort Sea, where freshwater met sea to create a vast puzzle of rivers and islands.

But Jack was having a hard time concentrating on the mundane tasks at hand. Something about that homework-addiction story was bugging her. Mashing the goggles over her eyes again, she reimmersed in the feed menu. Glancing through a set of commands, she searched for more information. “,” read one headline. Jack sucked in her breath. Could this clickbait story be about that batch of Zacuity she’d unloaded last month in Calgary?

The sub’s cargo hold was currently stacked with twenty crates of freshly pirated drugs. Tucked among the many therapies for genetic mutations and bacterial management were boxes of cloned Zacuity, the new blockbuster productivity pill that everybody wanted. It wasn’t technically on the market yet, so that drove up demand. Plus, it was made by Zaxy, the company behind Smartifex, Brillicent, and other popular work enhancement drugs. Jack had gotten a beta sample from an engineer at Vancouver’s biggest development company, Quick Build Wares. Like a lot of biotech corps, Quick Build handed out new attention enhancers for free along with their in-house employee meals. The prerelease ads said that Zacuity helped everyone get their jobs done faster and better.

Jack hadn’t bothered to try any Zacuity herself—she didn’t need drugs to make her job exciting. The engineer who’d provided the sample described its effects in almost religious terms. You slipped the drug under your tongue, and work started to feel good. It didn’t just boost your concentration. It made you enjoy work. You couldn’t wait to get back to the keyboard, the breadboard, the gesture table, the lab, the fabber. After taking Zacuity, work gave you a kind of visceral satisfaction that nothing else could. Which was perfect for a corp like Quick Build, where new products had tight ship dates, and consultants sometimes had to hack a piece of hardware top-to-bottom in a week. Under Zacuity’s influence, you got the feelings you were supposed to have after a job well done. There were no regrets, nor fears that maybe you weren’t making the world a better place by fabricating another networked blob of atoms. Completion reward was so intense that it made you writhe right in your plush desk chair, clutching the foam desktop, breathing hard for a minute or so. But it wasn’t like an orgasm, not really. Maybe it was best described as physical sensation, perfected. You could feel it in your body, but it was more blindingly good than anything your nerve endings might read as inputs from the object-world. After a Zacuity-fueled work run, all you wanted to do was finish another project for Quick Build. It was easy to see why the shit sold like crazy.

But there was one little problem, which she’d been ignoring until now. Zaxy didn’t make data from their clinical trials available, so there was no way to find out about possible side effects. Normally Jack wouldn’t worry about every drug freak-out reported on the feeds, but this one was so specific. She couldn’t think of any other popular substances that would get someone addicted to homework. Sure, the student’s obsessive behavior could be set off by a garden-variety stimulant. But then it would hardly be a medical mystery, since doctors would immediately find evidence of the stimulant in her system. Jack’s mind churned as if she’d ingested a particularly nasty neurotoxin. If this drug was her pirated Zacuity, how had this happened? Overdose? Maybe the student had mixed it with another drug? Or Jack had screwed up the reverse engineering and created something horrific?

Jack felt a twitch of fear working its way up her legs from the base of her spine. But wait—this shiver wasn’t just some involuntary, psychosomatic reaction to the feeds. The floor was vibrating slightly, though she hadn’t yet started the engines. Ripping off the goggles, she regained control of her sensorium and realized that somebody was banging around in the hold, directly behind the bulkhead in front of her. What the actual fuck? There was an aft hatch for emergencies, but how—? No time to ponder whether she’d forgotten to lock the doors. With a predatory tilt of the head, Jack powered up her perimeter system, its taut nanoscale wires networked with sensory nerves just below the surface of her skin. Then she unsnapped the sheath on her knife. From the sound of things, it was just one person, no doubt trying to grab whatever would fit in a backpack. Only an addict or someone truly desperate would be that stupid.

She opened the door to the hold soundlessly, sliding into the space with knife drawn. But the scene that met her was not what she expected. Instead of one pathetic thief, she found two: a guy with the scaly skin and patchy hair of a fusehead, and his robot, who was holding a sack of drugs. The bot was some awful, hacked-together thing the thief must have ripped off from somebody else, its skin layer practically fried off in places, but it was still a danger. There was no time to consider a nonlethal option. With a practiced overhand, Jack threw the knife directly at the man’s throat. Aided by an algorithm for recognizing body parts, the blade passed through his trachea and buried itself in his artery. The fusehead collapsed, gagging on steel, his body gushing blood and air and shit.

In one quick motion, Jack yanked out her knife and turned to the bot. It stared at her, mouth open, as if it were running something seriously buggy. Which it probably was. That would be good for Jack, because it might not care who gave it orders as long as they were clear.

“Give me the bag,” she said experimentally, holding her hand out. The sack bulged with tiny boxes of her drugs. The bot handed it over instantly, mouth still gaping. He’d been built to look like a boy in his teens, though he might be a lot older. Or a lot younger.

At least she wouldn’t have to kill two beings today. And she might get a good bot out of the deal, if her botadmin pal in Vancouver pitched in a little. On second glance, this one’s skin layer didn’t look so bad, after all. She couldn’t see any components peeking through, though he was scuffed and bloody in places.

“Sit down,” she told him, and he sat down directly on the floor of the hold, his legs folding like electromagnetically joined girders that had suddenly lost their charge. The bot looked at her, eyes vacant. Jack would deal with him later. Right now, she needed to do something with his master’s body, still oozing blood onto the floor. She hooked her hands under the fusehead’s armpits and pulled his remains through the bulkhead door into the control room, leaving the bot behind her in the locked hold. There wasn’t much the bot could do in there by himself, anyway, given that all her drugs were designed for humans.

Down a tightly coiled spiral staircase was her wet lab, which doubled as a kitchen. A high-grade printer dominated one corner of the floor, with three enclosed bays for working with different materials: metals, tissues, foams. Using a smaller version of the projection display she had in the control room, Jack set the foam heads to extrude two cement blocks, neatly fitted with holes so she could tie them to the dead fusehead’s feet as easily as possible. As her adrenaline levels came down, she watched the heads race across the printer bed, building layer after layer of matte-gray rock. She rinsed her knife in the sink and resheathed it before realizing she was covered in blood. Even her face was sticky with it. She filled the sink with water and rooted around in the cabinets for a rag.

Loosening the molecular bonds on her coveralls with a shrug, Jack felt the fabric split along invisible seams to puddle around her feet. Beneath plain gray thermals, her body was roughly the same shape it had been for two decades. Her cropped black hair showed only a few threads of white. One of Jack’s top sellers was a molecule-for-molecule reproduction of the longevity drug Vive, and she always quality-tested her own work. That is, she had always quality tested it—until Zacuity. Scrubbing her face, Jack tried to juggle the two horrors at once: A man was dead upstairs, and a student in Calgary was in serious danger from something that sounded a lot like black-market Zacuity. She dripped on the countertop and watched the cement blocks growing around their central holes.

Jack had to admit she’d gotten sloppy. When she reverse engineered the Zacuity, its molecular structure was almost exactly like what she’d seen in dozens of other productivity and alertness drugs, so she hadn’t bothered to investigate further. Obviously she knew Zacuity might have some slightly undesirable side effects. But these fun-time worker drugs subsidized her real work on antivirals and gene therapies, drugs that saved lives. She needed the quick cash from Zacuity sales so she could keep handing out freebies of the other drugs to people who desperately needed them. It was summer, and a new plague was wafting across the Pacific from the Asian Union. There was no time to waste. People with no credits would be dying soon, and the pharma companies didn’t give a shit. That’s why Jack had rushed to sell those thousands of doses of untested Zacuity all across the Free Trade Zone. Now she was flush with good meds, but that hardly mattered. If she’d caused that student’s drug meltdown, Jack had screwed up on every possible level, from science to ethics.

With a beep, the printer opened its door to reveal two perforated concrete bricks. Jack lugged them back upstairs, wondering the entire time why she had decided to carry so much weight in her bare hands.

Two: Booting

JULY 2, 2144

Sand had worked its way under Paladin’s carapace, and his actuators ached. It was the first training exercise, or maybe the fortieth. During the formatting period, it was hard to maintain linear time; memories sometimes doubled or tripled before settling down into the straight line that he hoped would one day stretch out behind him like the crisp, four-toed footprints that followed his course through the dunes.

Paladin used millions of lines of code to keep his balance as he slid-walked up a slope of fine grains molded into ripples by wind. Each step punched a hole in the dune, forced him to bend at the waist to keep steady. Sand trickled down his body, creating tiny scars in the dark carbon alloy of his carapace. Lee, his botadmin, had thrown him out of the jet at 1500 hours, somewhere far north in African Federation space. Coming down was easy. He remembered doing it before, angling his body in a configuration that kept him from overheating, unfurling the shields on his back until they cupped the wind, then landing with a jolt to his shocks.

But this wasn’t just another repeat of the same old obstacle course. It was a test mission.

Lee had told Paladin that a smuggler’s stash was hidden somewhere in the dunes. His job was to approach from the south, map the space, try to find the stash, and come back with all the data he could. The botadmin grinned as he delivered these instructions, gripping Paladin’s shoulder. “I tweaked some of your drivers just for this test. You’re going to float up those dunes like a goddamn butterfly.”

Now it was an hour until sundown, and Paladin’s carapace bent the light until it slid below the visible spectrum. To human eyes, his dark body on the dune’s summit would look like a shimmer of heat in the air, especially from a distance. That’s what he was counting on, anyway. He needed to get a sense of the area, its hiding places, before anyone figured out a bot was prowling.

Pale, reddish swells softened the landscape in every direction. The sand was totally undisturbed—if anyone had been walking around here, the wind had blown their tracks away. The stash had to be underground, if it was even here at all. Paladin stood still, lenses zooming and panning, searching for a glint of antennas or other signs of habitation. He cached everything in memory for analysis later.

There it was: a crescent of chrome unburied by wind. He scrambled down the dune, making hundreds of small adjustments to avoid falling on the slithering ground, getting a precise location on a portal that probably led to a buried structure below. He would yank it open and get back to the lab. Lee would clean the sand from his muscles, and there would be no more of this grinding discomfort.

As Paladin reached out, ready to pull or torque the lock mechanism, a hidden sniper tore his right arm off at the shoulder. It was the first true agony of his life. He felt the wound explode across his whole torso, followed by a prickling sear of unraveled molecular bonds along the burned fringes of his stump. Out of this pain bloomed a memory of booting up his operating system, each program calling the next out of nothing. He wanted to go back into that nothing. Anything to escape this scalding horror, which seemed to pour through his body and beyond it. Paladin’s sensorium still included his severed arm, which was broadcasting its status to the bot with a short-range signal. He’d have to kill his perimeter network to make the arm go silent. But without a perimeter he was practically defenseless, so he was stuck feeling a torment that echoed between the inside and outside of his body. Throwing himself down into the sand, Paladin used his wing shields to protect his remaining circuitry—especially his single biological part, nested deep inside the place where humans might carry a fetus.

He scrabbled with his remaining hand at the portal and it opened with a gasp, the air pressure differential seeming to inhale him. Another bolt smashed into the sand next to his head, puddling grains into liquefied glass where it hit. Hurling himself inside, Paladin caught one last glimpse of his arm. The fingers were still flexing, reaching for something, following their software commands even in death. As the door closed, his pain eased; a shield had blocked the arm’s hopeless data stream.

Paladin found himself in a lift whose dim, ultraviolet lighting marked the building as a bot facility—or, at least, a bot entrance to the facility. Humans would see nothing but darkness. Clutching his jagged stump, Paladin slumped to the floor in a jumble of disorganized feelings. With some effort, he distracted himself by watching a tiny display that showed how deep the lift was going. Forty meters, sixty meters, eighty meters. They stopped at one hundred, but from the faint echoes in the machinery, Paladin knew they could have gone a lot deeper.

The door slid back to reveal Lee flanked by two bots, one hovering in a blur of wings and one a tanklike quadruped with folded mantis arms. Paladin wondered if any of them had been responsible for blowing off his arm during a training mission that was supposed to be noncombat. He wouldn’t put it past them. Now Lee was grinning, and the bots weren’t saying anything. Paladin stood in a way that he hoped was dignified and ignored the physical anguish that flared through his body as he took in the scene.

“That was some seriously awesome combat shit,” Lee enthused before Paladin even stepped into the wide, foam-and-alloy tunnel. “See how that new climbing algorithm worked?” He slapped Paladin’s unwounded arm. “Sorry about your arm, though. I’ll fix that right up.”

The bots were still silent. Paladin followed the group as they walked down the tunnel, passing several doors marked in paint that reflected nothing but ultraviolet light. Visible to bot eyes only. Maybe this was some kind of bot training station? Was he about to be integrated into a fighting unit?

Down another tunnel they found what was obviously a mixed area, with paint reflecting in the visible spectrum, and several doorways too narrow to admit an armored bot like himself or the mantis. They stopped at an engineering station, where Lee printed a new arm and Paladin cleaned his joints with compressed air and lubricant.

The mantis beamed Paladin a hail. Hello. Let’s establish a secure session using the AF protocol.

Hello. I can use AF version 7.6, Paladin replied.

Let’s do it. I’m Fang. We’ll call this session 4788923. Here are my identification credentials. Here comes my data. Join us at 2000.

Fang’s request came with a public key for authentication and a compressed file that bloomed into a 3-D map of the facility. A tiny red tag hovered over a conference room forty meters below them. Judging by the map’s metadata, they were in a large military base operated by the African Federation government. It seemed that the bots here did the kind of work he’d been training for: reconnaissance, intelligence analysis, and combat. Paladin had just been invited to his first briefing. It was time to authenticate himself properly to his new comrade.

I’m Paladin. Here are my identification credentials. Here comes my data. See you there.

Lee finished the arm and tested Paladin’s stump with a voltmeter. The bot stood on a charging pad, drawing power for the batteries that tunneled through his body like a cardiovascular system. Generally he relied on the solar patches woven into his carapace, but pads were faster.

“No problem, no problem,” the botadmin mumbled. It was his favorite phrase, and was in fact the first string of natural language that Paladin had ever heard, in the seconds after booting up for the first time three months ago. The arm was bonding to his stump now, and the torture of his injury became a tingle. Lee used a molecule regulator to knit the arm’s atomic structure into an integrated body network, and as it connected Paladin could feel his new hand. He made a fist. The right side of his body felt weightless, as if the pain had added additional mass to his frame. Giddy, he savored the sensation.

“Gotta go, Paladin—I’ve got a bunch of other shit to do.” Lee’s dark hair fell across one of his eyes. “Sorry I had to shoot you there, but it’s part of training. I didn’t think your whole arm would come off!”

How many times had Paladin looked into this human face, its features animated by neurological impulse alone? He did not know. Even if he were to sort through his video memories and count them up one by one, he still didn’t think he would have the right answer. But after today’s mission, human faces would always look different to him. They would remind him of what it felt like to suffer, and to be relieved of suffering.

When Paladin arrived at the meeting location, two humans were sitting in chairs, while Fang and the hovering bot remained at attention. Paladin announced his presence with a beamed hail to the bots and a vocalized greeting to the humans, though protocol kept the rest of his communication in human range. He took up a position next to Fang, bending his legs until he was at eye level with the humans. In this position, knee joints jutting out behind him and dorsal shields folded flat against his shoulders, Paladin looked something like an enormous, humanoid bird.

“Welcome to Camp Tunisia, Paladin,” one of the humans said. He had a tiny red button on his collar bearing the letters “IPC” in gold—it marked him as a high-ranking liaison from the Federation office of the International Property Coalition. “This will be your base for the next few days while we brief you and your partner Eliasz on your mission.” He gestured to the other human, a slim man with pale skin, curly dark hair, and wide brown eyes, wearing Federation combat fatigues. Paladin noticed that Eliasz’ right hand was balled into a fist very much like his own. Maybe Eliasz was also remembering something painful.

The liaison projected some unopened files into the air over the table. “We’ve got a serious pharma infringement situation, and we need it stopped fast and smart,” he said. One of the files dissolved into the corporate logo for Zaxy, and then into a tiny box of pills labeled Zacuity.

“I assume you’ve heard of Zacuity.”

“It’s a worker drug,” Eliasz replied, his face neutral. “Some of the big companies are licensing it as a perk for their employees. I’ve heard it feels really good. Never tried it myself.”

The liaison seemed offended by Eliasz’ description. “It’s a productivity enhancer.”

Fang broke in. “We’ve got reports of people buying pirated Zacuity in some of the northern cities in the Free Trade Zone. Some recon bots found about twenty doses in a First Nations special economic holding near Iqaluit. Nobody can prosecute there—it’s totally outside IPC jurisdiction—so there have been no arrests yet.”

The liaison brought up video of a hospital room, packed with humans strapped to beds, twitching. He continued. “Zaxy will take legal action later. But right now, we need an intervention. This drug is driving people nuts, and some are dying. If it gets out that this is Zacuity, it could be a major financial loss for Zaxy. Major.”

The liaison looked at Eliasz, who stared straight at the projection of the hospital, watching the tiny, struggling figures loop through the same tiny struggles again.

“Zaxy’s analysts think the Zacuity is being pirated here in the Federation, in a black-market lab. Obviously, this situation could seriously endanger the Federation’s business partnerships with the Free Trade Zone. We need to find out for sure one way or the other, and that’s why we need you.” The delegate looked at Paladin. “You’ve both been authorized by the IPC to track the pirated drug to its source, and stop it. We’ve got a few leads in Iqaluit, and they all point to one person.”

The afflicted Zacuity eaters dissolved into an enhanced headshot of a woman, obviously constructed from several low-quality captures. Her cropped black hair had a glint of gray, and a fat scar that started on her neck snaked into the collar of her coveralls.

“This is Judith Chen—she goes by the name Jack. We suspect she’s working with one of the biggest pharma pirating operations in the Federation. We know she’s connected with some pretty shady manufacturers in Casablanca, but she’s got a legit shipping fleet. She ferries for spice and herb companies to the Zone—lots of stinky little boxes. Perfect cover. We think she might be the one who’s smuggling the drugs from here across the Arctic.”

Fang vocalized, “We’ve been watching her for years. Never been able to catch her red-handed, but we know she’s got connections with people in the Trade Zone who are suspected dealers. Plus, she’s a trained synthetic biologist. It all fits together. If we can get to her, I think we can shut down these pirate shipments.”

“She’s also an anti-patent terrorist,” Eliasz added quietly. “Spent several years in jail.”

“The official charge was not terrorism. It was conspiracy to commit property damage,” said Fang. “She was only in jail for a few months, and then she fled from Saskatoon to Casablanca. We think that’s how she made the connections that she’s using for her pirating operation.”

“Once we’ve got her, we just can hand her over to the Trade Zone on a plate,” added the liaison. “Piracy stopped. Justice done. Everybody’s happy.”

“It still sounds like terrorism to me,” Eliasz said, looking directly at Paladin. “Don’t you agree?”

Nobody had ever looked at him quite like that, as if he could have an opinion about anything beyond how his network was functioning. The bot’s mind spiraled through what he’d been taught about terrorism, quickly compiling an index of images and data that required nothing but a crude algorithm to reveal a pattern: pain and its echo, across millions of bodies over time. Paladin did not have access to the nuance of political context, nor did he have the urge to seek it out. He had only this man’s face, his dark eyes sending an unreadable message that Paladin wanted desperately to decrypt.

How could he look at Eliasz and say no?

“It does sound like terrorism,” Paladin agreed. When Eliasz smiled, the planes of his face were asymmetrical.

Fang broke protocol for an instant, beaming to his hovering companion in an off-the-record session. Words of wisdom from the newbie, who has never seen terrorism in his life. 🙁

Three: Private Property

JULY 2, 2144

When does the thinnest smear of genetic material left by spilled blood finally evaporate? At some point it becomes invisible to human eyes, its redness dimmed by water and the mopper’s crawl, but there are still pieces left—shattered cell walls, twists of DNA, diminishing cytoplasm. When do those final shards of matter go away?

Jack watched the rotund blob of the mopper as it swished back and forth across a pinking stain that had once been a red-black crust on the floor of the control room. A blue glare of water-filtered sunlight came directly through the glass composite in the windows, blinding her until she dropped her eyes back down to the stain. She’d disposed of the body hours ago, its legs lashed to the cement blocks. By now, it would be frozen deep under the water.

Jack hadn’t had to kill anyone for a long time. Usually, in a tight situation, she wasn’t in the middle of the ocean. She could run away instead of having to fight. She ran a hand through the salt-stiffened tufts of her hair, wanting to vomit or cry or give up again in the face of the hopeless, endless pharma deprivation death machine.

That last thought make her crack a self-chiding smile. Pharma deprivation death machine. Sounded like something she would have written in college and published anonymously on an offshore server, her words reaching their destination only via a thick layer of crypto and several random network hops.

Black pharma smuggling wasn’t exactly the job she’d imagined for herself thirty years ago, in the revolutionary fervor of her grad student days. Back then, she was certain she could change the world just by making commits to a text file repository, and organizing neatly symbolic protests against patent law. But when she’d finally left the university labs, her life had become one stark choice: farm patents for shitty startups, or become a pirate. For Jack, it wasn’t a choice at all, not really.

Sure, there were dangers. Sometimes a well-established pirate ring in the Federation would find a few of its members dead, or jailed for life—especially if a corp complained about specific infringements. But if you kept a low profile, modest and quiet, it was business as usual.

But not usually business like this: cleaning up after a guy she’d killed over a bag of pills and a bot.

Where the hell had he even come from? She gestured for the sub’s local network, flicking open a window that gave her a sensors’ perspective on the mottled surface of the ocean from a few feet below. Nothing but the occasional dark hulk of icebergs out there now. Maybe she’d really started to lose it after all her years of vigilance? He’d exploited some obvious hole in her security system, fooling the ship’s perimeter sensors until he was on board and stuffing boxes of her payload into his rucksack. Selling a bag of those dementia meds wouldn’t have gotten him much more than a year’s worth of euphorics and gambling in some Arctic resort right on the beach.

The dead fusehead was the least of her problems right now, though. Jack needed to figure out whether something had gone wrong with her batch of reverse-engineered Zacuity. She still had some samples of the original drug she’d broken down to its constituent parts, along with plenty of her pirated pills. Jack tossed the original and pirated versions into her chem forensics rig, going over the molecular structures again with a critical eye. Nothing wrong there—she’d made a perfect copy. That meant the issue was with Zacuity’s original recipe. She decided to isolate each part of the drug, going through them one by one. Some of them were obviously harmless. Others she marked for further examination.

Jack finally narrowed the questionable parts down to four molecules. She projected their structures into the air, regarding the glittering bonds between atoms with a critical eye. A quick database search revealed that all of these molecules targeted genes related to addiction in large parts of the population. Jack paused, unable to believe it.

Zaxy had always placed profit over public health, but this went beyond the usual corporate negligence. International law stipulated that no cosmetic pharmaceuticals like productivity drugs or euphorics could contain addictive mechanisms, and even the big corps had to abide by IPC regulations. Her discovery meant that Zacuity was completely illegal. But nobody would figure that out, because Zaxy was rolling it out slowly to the corps, keeping any addictions carefully in check. When Zacuity came out of beta, the drug would be so expensive that only people with excellent medical care would ever take it. If they got addicted, it would be dealt with quietly, at a beautiful recovery facility somewhere in the Eurozone. It was only when somebody like Jack started selling it on the street that problems and side effects could be magnified into something more dangerous.

Jack was torn between rage at Zacuity and rage at herself for bringing their shitty drug to people without health resources. Hundreds of people might be eating those pills right now, possibly going nuts. It was a horrific prospect, and Jack wasn’t prepared to deal with the enormity of this problem just yet. Reaching into the pocket of her newly washed coveralls, she pulled out some 420 and sparked it up. Nothing like drugs to take the edge off drug problems. Besides, she had unfinished business with that bot behind the locked door of her cargo hold. He might prove to be unfixable, but at least that wasn’t her fault.

Jack expected the bot would still be in the same spot where he collapsed, eyes wandering under the control of some shit algorithm yanked off the net. But he wasn’t. Jack squinted, trying to figure out why the bot was huddled into a shadow where the wall met the floor. She’d started the ship moving again, and bubbles slid past the dark portals.

He was sleeping.

Suddenly Jack realized why the bot could look so beaten up but still show no signs of an alloy endoskeleton. This wasn’t a biobot—it was just plain bio. A human.

She leaned against the bulkhead and groaned quietly. A damaged bot was almost always fixable, but a damaged human? She had the goods to repair a mutating region in his DNA, and purge his body of common viruses, but nothing could fix a wrecked cognition. As she pondered, the hunched figure sat up with a start and stared at her with eyes whose emptiness was now far more awful than bad software. She wondered how long he’d been indentured to the dead thief. There was a number branded on his neck, and he’d obviously been following orders for a long time.

The 420 gave Jack a kind of philosophical magnanimousness, and with it a sense of resigned obligation to this kid. It wasn’t his fault that his master had decided to rob an armed pirate in the middle of nowhere. She’d do what she could to help him, but that wasn’t much.

“Do you want some water?” she asked. “You look like you could use it.”

He scrambled up suddenly, grabbing the edge of a crate to keep his balance, and she realized he was actually rather tall—taller than she was, though so malnourished that his height made him seem even more fragile. If things got dicey, it would be no trouble for her to overpower him, snap his neck, and toss him into the airlock.

“Please,” he said. “And food, too, if you can spare it.” His English accent was pure middle-class Asian Union, which wasn’t exactly what you expected from a kid with a brand on his neck.

“Come on, then.” Jack touched his shirtsleeve lightly, careful not to hit exposed skin. She led him down the spiral staircase from the control room into the wet lab/kitchen, where she booted up the cooker and gestured for broth and bread. He sagged into her chair at the tiny table, the wings of his shoulder blades showing through his thin shirt as he hunched over and stared at his hands.

She put the food in front of him. “I’m Jack.”

He ignored her, taking a sip from the bowl, then dunking the bread in and biting off a chunk. Jack leaned on the counter and watched, wondering if the kid even had a name. Families with nothing would sometimes sell their toddlers to indenture schools, where managers trained them to be submissive just like they were programming a bot. At least bots could earn their way out of ownership after a while, be upgraded, and go fully autonomous. Humans might earn their way out, but there was no autonomy key that could undo a childhood like that.

“I’m Threezed,” he responded finally, breaking Jack out of her spaced reverie. He’d swallowed about half the broth and his face didn’t look quite as blank as it had before. It was hard to miss the fact that the last two numbers branded onto his neck were three and zed. That scar was his name, too. Jack folded her arms over the sudden stab of sympathy in her chest.

“Nice to meet you, Threezed.”

Four: Iqaluit

JULY 4, 2144

Their bodies would have to work together, even when they were far apart. That was Eliasz’ rationale for climbing sand dunes with Paladin for two days while the IPC liaison drank endless cups of sweet milk tea and gestured in mute frustration, swiping through all the messages materializing from the projectors on his glasses.

Doing exercises alongside someone else was a new sensation for Paladin. He had always been in radio contact with Lee or another botadmin, but their voices were more like programs that guided him from inside his instincts. His botadmins never stopped, looked at him, and talked about how they missed the weather in Europe.

“I hate the weather here,” Eliasz muttered, crouching down at the top of a dune. He glanced at Paladin and then settled into a sitting position. It was 0800, and Paladin was testing his reflexes in sand again, learning to keep the bulk of his carapace low and his sensors moving across a wide spectrum. He was in that position now, squirming on his elbows and knees, listening to Eliasz talk and tuning the public botnet.

You are all. I am Raptor. Here comes my data. I am leaving on a mission at 1300. Going to Congo for a plague intervention. Wish me luck. Back in 48 hours.

“I’d rather have cold and wet, like in the central Eurozone,” Eliasz continued, pushing sweat from his forehead into his hair with an outspread hand. “People say they can’t stand Warsaw because it’s so cold, but I guess you always love the weather where you grew up—even if you never want to go back. Where are you from, Paladin?”

You are all. I am Cldr. Here comes my data. I need three bots to help with weapons cargo drop-off. Location attached.

Paladin paused in his squirming, his head nearly touching Eliasz’ leg where it rested in red sand. He wasn’t sure what the appropriate answer to that question would be, since he hadn’t really been alive long enough to be from anywhere in particular.

“I suppose I am from the Kagu Robotics Foundry in Cape Town,” he vocalized.

“No, no, no,” Eliasz shook his head violently, then rapped his knuckles on Paladin’s lower back. “I mean, where are you from originally? Where is your brain from?”

Under its layers of abdominal shielding, Paladin’s biobrain floated in a thick mixture of shock gel and cerebrospinal fluid. There was a fat interface wire between it and the physical substrate of his mind. The brain took care of his facial recognition functions, assigning each person he met a unique identifier based on the edges and shadows of their expressions, but its file system was largely incompatible with his own. He used it mostly like a graphics processor. He certainly had no idea where it was from, beyond the fact that a dead human working for the Federation military had donated it.

Eliasz spoke again. “Isn’t it important to you to know who you really are? Why you feel what you do?”

None of Paladin’s emotions or ethics were processed in his human brain. But then Eliasz looked right into the sensor array mounted on Paladin’s face, his eyes dark and attentive. Suddenly Paladin didn’t want to explain his file system architecture anymore.

“I don’t know where my brain is from,” he replied simply. “I can’t access its memories.”

He could sense the tension mounting in Eliasz’ body. Electricity skipped across the surface of his skin. Over the thousands of seconds they’d spent together, Paladin had noticed that Eliasz tended to vacillate between these intense, emotional conversations and total silence.

“They should let you remember,” he growled. “They should let you.”

If Eliasz couldn’t get that wish granted, at least he did get something else he wanted. It came in the form of an incoming message for Paladin, part of a securely encrypted session.

You are Paladin. I am Fang. Remember the secure session we created before? Let’s use it again. Here comes my data. Final mission meeting is at 0900. Bring Eliasz.

I agree to use our already-established secure session. I am Paladin. Where are we going?

Balmy shores of the Arctic, looks like. You’ll be tracking down some of Jack’s connections there, trying to figure out where she hides her stash.

I am prepared to meet you in 30 minutes with Eliasz. This is the end of my data.

The two bots closed out their session after an exchange of map coordinates, which were for the same room they had used over the past two days for mission planning.

“Good news,” Paladin vocalized to Eliasz, who was still staring at him. “We are about to leave for the northern Free Trade Zone, where the temperature is much lower.” Eliasz said nothing, but his heart rate had slowed down. The two set off across the dune tops to find a portal and receive their orders.

Though the mission was fairly small-scale and routine, it held a special significance for Paladin because it meant he’d crossed over from development to deployment. Today marked the first day of his indenture to the African Federation. International law mandated that his service could last no more than ten years, a period deemed more than enough time to make the Federation’s investment in creating a new life-form worthwhile.

Though he was just beginning his term of indenture, Paladin had heard enough around the factory to know that the Federation interpreted the law fairly liberally. He might be waiting to receive his autonomy key for twenty years. More likely, he would die before ever getting it. But he wanted to survive—that urge was part of his programming. It was what defined him as human-equivalent and therefore deserving autonomy. The bot had no choice but to fight for his life. Still, to Paladin, it didn’t feel like a lack of choice. It felt like hope.

JULY 5, 2144

The bulbous, fisted forearms of the Baffin Island skyline came into view from kilometers away as the jet shot over the Arctic Sea. Even at this distance, Paladin could see the movement of thousands of wind turbines, making the outlines of each building shimmer slightly. Soon, he could pick out the chemical signature of the lush farms that rose in tiered spirals around each complex. Northern cities ringing the Arctic spent all summer absorbing as much solar as possible, taking their farms through two crop seasons while the days were long. The whole city was deep into growing season.

By the time they’d passed over the outer islands and hit the airspace over Baffin, Eliasz was wide-awake. Paladin heard the change in Eliasz’ breathing and knew he must have ordered a wake-up signal from his perimeter when they were arriving at Iqaluit. Now the city was sprawled beneath them, its domes a glittering crust at the vertex of an acutely angled bay that cut deeply into the huge island.

“Iqaluit is an ugly city,” Eliasz grunted, joining Paladin at the window. “Its domes are modeled on the ones in Vegas—you know it?”

“A domed city in the western desert of the Free Trade Zone,” Paladin vocalized.

“It’s the center of the human resources industry. A lot of bad guys there. Black-market slave shit. People there don’t value human life so they build with this cheap crap that lets in way too much ultraviolet. Iqaluit looks exactly the same—except a lot cleaner and newer.”

Paladin wondered if Eliasz was opposed to the system of indenture. There were entire text repositories that focused on eliminating the indenture of humans. Their pundits argued that humans should not be owned like bots because nobody paid to make them. Bots, who cost money, required a period of indenture to make their manufacture worthwhile. No such incentive was required for humans to make other humans.

Regardless of what pundits thought, the vast majority of cities and economic zones had some system of human indenture. And Vegas was where the humans sold themselves. Its domed complexes were almost entirely devoted to processing, training, and contracting human resources. Like Vegas, Iqaluit had been built fast; it was all skyscrapers and domes. But a cursory data scan revealed few commonalities between the two cities beyond that.

“There are very few indentured humans here,” Paladin pointed out.

“Sure. The bad guys are different, but there are still bad guys,” Eliasz said, his elevated blood pressure appearing to Paladin like a reddish haze around the outline of his body. “The place is crawling with pirates. Everything here is stolen.”

They skimmed the runway and Eliasz stood up, instinctively touching his forehead, shoulders, and belt to verify his perimeter and its local network of weapons. “I always feel like I’m crossing myself when I do that,” he growled, heart speeding up in agitation. “You know what I mean?”

“The gestures are similar,” Paladin replied.

“My father was a true believer,” Eliasz said, his voice so low that only a bot could have heard it. Then, suddenly, his demeanor shifted; the man forced his breathing into a regular rhythm and it was no longer easy to read his emotional state from a distance.

“Where are we going first, Paladin?” Eliasz grinned, his eyes seeking out the five visual sensors on the robot’s head, set above diagonal planes that framed his face like an abstract version of human cheeks. They had about three dozen possible destinations, including addresses for several alleged associates of Jack’s and a few of her favorite restaurants.

“We should begin with the closest home addresses, question the people there, and then attempt to corner Jack based on the information they provide. As a last resort, we could monitor the restaurant secfeeds for Jack’s biometrics.”

Eliasz barked a laugh. “You don’t know much about HUMINT, do you, Paladin?”

Human intelligence gathering was not a priority during Paladin’s training. When the bot did not respond, Eliasz stopped laughing. “Sorry, buddy. It’s better to start with the restaurants. But first, we need some gear.”

Near the frayed landing strips of the airfield was a junk shop, its corrugated steel exterior at least a hundred years old. Low and long, it was designed to withstand the weather and retain heat. Inside, molecules associated with cotton fibers, bleach, and fuel floated through Paladin’s sensors. Eliasz talked to a man behind the counter with a cybernetic chest and arms, who started downloading a local map and intel upgrades into Eliasz’ geosystems. Paladin stepped closer and tuned the signal connecting the two men’s devices, decrypting and copying the data to his own memory.

“This is my partner, Paladin,” Eliasz said suddenly, throwing a warm arm around Paladin’s carapace. His fingers gripped the bot’s shoulder blade where his shields emerged. Paladin could feel each whorl of Eliasz’ prints. He unconsciously mapped them to several databases, most of which were swollen with information noise that hid Eliasz’ real identity. The prints matched a dead professor in Brussels, a small-time entrepreneur in Nairobi, a priest in Warsaw, and an indentured woman who belonged to Monsanto in the Free Trade Zone. There were dozens of other matches, spinning outward into a vast snarl of false social network connections and contradictory government records.

“Paladin, I’m Yardley,” the man said, extending his fabricated hand to meet Paladin’s.

“We’re going undercover and I need to look a little less pro,” Eliasz said, glancing at Paladin. “And he needs to look a little less shiny.”

Ten minutes later, Eliasz had stripped down to the glittering nodes of his perimeter system and was pulling jeans and a cotton shirt over the invisible network of nanowire that connected to the perimeter below his skin. Paladin put his pressure sensors back online experimentally, testing to see where he could still feel the sting of the dents and scratches Yardley and Eliasz had administered.

“We need to get some information on Jack, and the only way to do that is to look like the kinds of guys who would work with her,” Eliasz said. “You can keep quiet most of the time, but try to make errors once in a while, like your brain is damaged or something.”

Paladin said nothing as he finished restarting the processes that made up his sensorium.

“OK,” Eliasz muttered, then went over their story again. “I’m a chem admin who got laid off from PharmPraxis; you’re my indentured assistant. I’m willing to sell some of PharmPraxis’ formulas for the right price. You watch everything, man—do what you’re made for.”

“I will,” said Paladin. He wanted to please Eliasz. Paladin was sure that wasn’t just some indenture algorithm weighting his decision matrix; it was his true desire.

The sea winds maintained Iqaluit’s outdoor temperature at a steady twenty degrees Celsius and lifted a hank of Eliasz’ hair as Paladin tread quietly beside him. The sun was low enough on the horizon to signal evening, though it was still bright outside. Arctic summer meant there would be only an hour without sunlight this evening. By then, Eliasz hoped to be feigning drunkenness at the Lex, a noodle-and-beer joint that was one of Jack’s regular hangouts. Footage showed that she met up with some of her local connections there.

Paladin pushed the doors inward and ducked into a steamy room filled with molecules released by ginger and other crushed spices. He catalogued them for later analysis. You never knew when the distinct chemical signature of a place would turn out to be useful information. Crowded benches bowed under the weight of local fish farmers and students from the university chattering loudly about proteomics. Everybody was flushed from alcohol and bowls of scalding-hot noodle soup that teetered on every scarred and uneven foam table.

It would be an easy crowd to disappear in, Eliasz subvocalized to Paladin, especially if you looked like a farmer but your politics matched those of the radical students. Paladin accessed an image of Jack he’d stored in memory. She didn’t look exactly like a farmer, but he could see how she might blend if she wore waterproofs.

They sat down at the edge of a table full of extremely drunk students who were playing some kind of game with their goggles that involved a lot of footage-sharing and shots of Saskatchewan vodka. Eliasz ordered seafood noodles and Paladin made sure his right leg trembled as he hunkered down, as if he were desperately in need of a firmware upgrade. It caught the attention of one of the students right away.

“Need some help with that?” A jovial woman with dark eyes and bobbed black hair gestured vaguely at his leg. “We’ve got a free botware archive on the university servers.”

Paladin said nothing.

“We haven’t had much money for repairs.” Eliasz shrugged. “I’m just looking for work after the layoffs at PharmPraxis down south.” That caught the attention of more students at the table.

“More layoffs, eh?” asked one with a prairie lilt in his voice.

“Damn patent hoarders,” Eliasz said, his voice low. He was taking a risk, trying to suss out whether these students were the kinds of radicals who ran with pirates. Paladin noticed that Eliasz had changed his posture subtly, slouching and pulling his bangs over his eyes in a way that made him seem younger. He could pass for a postgraduate, and it was clear these drunk bio hackers were already responding to him as a peer. Paladin briefly admired this bit of HUMINT artistry, then considered that some of the records associated with Eliasz’ prints placed him at twenty-nine years old. Perhaps those records were accurate, at least in respect to the man’s age.

“Seriously,” said the woman who had offered Paladin access to her fabbers. “They rake in so much cash from all that IP and then treat their developers and admins like shit. It’s patent-farm bullshit. I’m Gertrude, by the way.”

“Ivan,” said Eliasz, “and this is my bot Xiu. He’s having a little trouble with his speakers.” Eliasz had picked a nym for Paladin that was more commonly given to women, but gender designations meant very little among bots. Most would respond to whatever pronoun their human admins hailed them with, though some autonomous bots preferred to pick their own pronouns. Regardless, no human would think twice about calling a bot named Xiu “he.” Especially a bot built like Paladin, whose hulking body, with dorsal shields spread wide over his back, took up the space of two large humans.

“Want me to hook you guys up with some fixes for Xiu?” Gertrude asked. Eliasz pretended to ponder, as he slurped his noodles.

“These are spicy,” he said, ignoring the fact that several of Gertrude’s friends were now looking at him and Paladin.

“We’re heading back to the lab after dinner, to check on a few processes we need to run overnight,” said the guy from the prairies.

“That would be really nice of you.” Eliasz feigned uncertainty as he fiddled with his chopsticks.

“Yeah, you should come.” Gertrude confirmed the invitation as if they had already been persuaded. “Sound good to you, Xiu?”

Paladin said nothing.

A group of five students led Eliasz and Paladin through streets illuminated by the long-wavelength light of a late-night sunset. At last they reached an arched sign covered in Inuktitut and English words welcoming them to University of the Arctic’s Iqaluit campus. It was the region’s wealthiest university and a feeder school for dozens of top biocoms and pharma corps. At this time of night it was fairly quiet, although as they neared the science buildings, Paladin picked out more and more windows radiating visible light.

Eliasz was describing his imaginary job at PharmPraxis with what sounded like genuine bitterness. The story was calculated to bring out sympathies in his audience. “I took a job in chem admin right out of university,” he said, “and they put me on a drug that died in trials. Took a year, but they wound up sacking my whole team. If your drug doesn’t get to market, well…” Eliasz trailed off.

“What do you work on?” asked Gertrude. “There are tons of jobs for chem admins around here.”

“I design algorithms that look for interesting emergent properties in organic molecules.”

A tall man with cheap glasses was walking in step with them. “Not my area, but I bet we could find you something, Ivan,” he said. His accent definitely wasn’t local—Paladin did a quick comparison between the tall man’s vowels and those of four hundred other regional accents in English. The best approximation was northern Federation, where Paladin and Eliasz had just been stationed.

“Thanks, um…”

“Youssef,” said the man. He easily met Paladin’s face sensors with his eyes; the bot and the man were the same height. “Pleased to meet you both,” he added.

They reached the Life Sciences complex and Gertrude dug through her pocket for what turned out to be a rather archaic password management device. She waved the tiny lump of plastic in the air when they reached an ash cement building, and the building’s network replied by opening a set of double doors.

Paladin noticed Youssef glance quickly at the sensor-flecked paint of the interior hallway, reflecting the gang of gradually sobering students dully as they passed through and began shedding their jackets. Gertrude, Youssef, and their friends worked on a theoretical and underfunded subject related to protein mutation and aesthetic decision-making. Their lab was in the basement, its equipment at least two generations behind current models. The walls were covered in signs and stickers stolen from other labs. “DANGER! DO NOT TOUCH THE MAGNET!” read a particularly large one over their sequencing cluster. “LIVE CRICKETS” read another.

“Here we are,” Gertrude said, gesturing for light. “Xiu, there’s our printer. The network is called PolarBunnies and it’s open.” She gestured again. “Help yourself to whatever.” Paladin walked carefully around several tables laden with cooling units and test tubes. He printed up some chips while Eliasz made small talk.

As the printer spat out nanoscopic threads, Eliasz managed to bring the conversation back around to those goddamn patent hoarders whom he really had a mind to fuck over somehow.

Youssef was tense with excitement, his body radiating identification with Eliasz’ tale. It was obvious he was about to speak several seconds before he did. “So how would you get back at a company like PharmPraxis for what they did?” Youssef asked. “I mean, how far would you be willing to go?”

“You really want to know? This doesn’t go outside this lab, OK?” Eliasz asked. Everybody was staring at him.

“Absolutely,” enthused Gertrude.

“I’ve got the formula for this patent-pending drug they’re in trials with right now. If somebody else brings it to market first, they’d never be able to claim prior art, because they based it on a molecule they got gray market from some unlicensed lab in the Brazilian States.” Eliasz paused, then gave his best shaky laugh. “I mean, I probably wouldn’t do anything with it, but I could. I really did take the formula.” He patted his hip pocket as if he’d saved the data in a physical medium and stashed it in his pants.

Youssef couldn’t take his eyes off the imaginary data in Eliasz’ pants. Paladin was getting weird readings off his brain: The guy was too excited, almost like he was on drugs or suffering a neurological aberration.

“You should do it,” he blurted out.

“Shut up, Youssef,” said Gertrude, who was checking a box full of samples with a small mass spectrometer. “That’s a serious fucking crime. Not like reverse engineering some old drug that’s about to go public domain anyway.”

It was Eliasz’ opening and he took it. “You’ve reverse engineered drugs before?”

Gertrude snorted. “Barely. He decompiled some Glizmer freshman year and sold copies of it to half our dorm.”

“That Glizmer worked.” Youssef looked angry. “And you know it’s more than that, Gertrude.”

Paladin watched anxiety push blood into Gertrude’s cheeks. Youssef’s lips tensed up. The tall man with the North Federation accent was taking a serious risk talking about this in front of a stranger. Paladin was impressed: Eliasz knew how to make people trust him. Would Youssef spill some serious intel? Apparently, yes.

“If you’re serious, you should meet some friends of mine whose labs aren’t funded by Big Pharma.” Youssef’s voice broke on the word “friends,” and Paladin realized the man’s body was still passing through the final stages of puberty.

Gertrude broke in, her heart rate elevated. “You know, Youssef, not everybody wants to break the law to prove a point.”

Eliasz shrugged like he hadn’t noticed any tension. “I don’t have anything against meeting new people,” he said to Youssef.

JULY 6, 2144

The next day, Paladin and Eliasz returned to the Lex in the late afternoon, long enough before happy hour that the crowds were thin. A few groups of students were quietly studying on their goggles, and a lonely farmer was nursing vodkas at the bar. Across the table from Eliasz and Paladin, his face slightly obscured by soup steam, was Youssef’s friend Thomasie, who wasn’t funded by Big Pharma.

He certainly looked the part. Thomasie’s black hair was gelled into a stylish tangle around his face, and certain fibers of his shirt glowed with the faded logo of a Freeculture org that had died in the 2120s. It was hard to say if he’d kept the shirt for twenty-five years, or simply bought an item artfully frayed and faded to look authentic. Thomasie had a way of leaning in when he talked, as if everything he was saying brought you into his confidence. Unlike Youssef, he had control of his flush responses and heart rate. It was hard to tell when he was lying, though the very evenness of his readings gave something away. He was masking emotional reactions to everything around him.

“Youssef tells me you worked at PharmPraxis and are looking for something new.” Thomasie looked straight at Eliasz, then glanced at Paladin. “That’s a pretty sweet bot you got on a chem admin’s salary.”

“I inherited him from my mother when she died.”

“I see. So what exactly is it that you did at PharmPraxis?”

“Algorithms.”

“And you had access to patent-pending designs, eh?”

Eliasz and Paladin stared at Thomasie and said nothing.

“Youssef told me you were interested in talking to me about some designs you saw.”

Silence was a good way to get additional information, to make the other person commit to the transaction first.

Thomasie tapped his index finger on the table slowly and continued. “My colleagues and I would be interested in taking a look at any designs you might have. We pay for good IP, no questions asked.”

At last Eliasz prepared to speak. Paladin measured the seconds it took for him to ramp up, heard him stabilize his breathing and blood pressure.

“I have the file on me. When do you want to see it?”

Paladin noticed that Eliasz failed to talk specific prices. He was trying to sound like a newbie at this. Perfect for a disgruntled ex-employee.

Thomasie caught the naïveté, and relaxed. He figured he had this one well in hand.

“We can go right now. My car is outside.”

They drove fifty kilometers outside city limits, the solar farms of South Baffin whipping past like vast regattas of smooth black sails. Youssef was drumming on the window and ignoring Paladin while Thomasie and Eliasz sat up front and talked.

After turning on several dirt roads, they reached a newish farm in the middle of a solar field. Its main building was an arched wall of thick glass set deeply into a grassy hill that rose like a green bubble out of a sea of dark, boxy solar antennas dribbling hydrocarbons into underground tanks. A woman stepped out of a door cut into the glass wall, releasing a blast of sound. Someone inside was listening to a loud news feed. The woman’s arms tensed as two overclocked matter cutters powered up beneath her sleeves.

Based on the pattern broadcast by Youssef’s eye movements as he scanned the area, Paladin considered it statistically unlikely that he’d been here before. This would be a test for Youssef as well as Eliasz.

“Thomasie.” Though the woman greeted Thomasie, she continued to block the door as they approached. Paladin noticed the driveway was fabbed to be impossibly smooth and warm; suspended inside its foam were long strands of nearly invisible wire that would radiate a gentle heat when the weather turned.

“Hi, Roopa.”

As Thomasie led them past Roopa’s barely concealed weapons, she gave Paladin a long look, eyes lingering on his shields. The room beyond her was illuminated by carefully reflected natural light, and trees grew out of the moss-covered floor. Nearly every piece of furniture was a living bonsai. One red light from a small industrial fabber blinked in the corner, exchanging data in a system encrypted so well that Paladin could only access information about the house climate. Somebody had burned serious money on this little farmhouse.

Thomasie led them to a round room with a conference table that grew out of the floor, its surface a carefully engineered weave of branches. The ceiling was perforated by a spiral staircase whose fabbed metal skeleton clanged and shook as three people came down to meet them. Like Thomasie, the others wore their expensive clothing carefully disheveled.

Iqaluit was a big town, but it wasn’t that big. If Jack was smuggling pharma through here, she was probably dealing with these guys in some way. They might be outsourcing the production of black pharma to her Federation labs, or selling her wares through their connections in the north. Even if they weren’t directly doing business, these people surely existed at the center of a local social network that brought together anti-patent radicals, pirates, and millions of people desperate for cheap drugs. If he and Eliasz could gain access to that network, they’d find Jack.

“Call me Bluebeard,” said one of the people who had just descended the stairs. She was wearing blue waterproofs and no shoes. Her dark hair fell in a wavy tangle across her face, nearly obscuring the fabric sensor patch that covered her left eye socket. From the tension in her shoulders and back, it was clear she’d been working with her hands for several hours—though whether it was at a gesture console or in the fields, Paladin couldn’t tell. “These are my colleagues, Blackbeard and Redbeard.” She pointed at two pale-skinned men whose clothing did not match their nyms. “Welcome to Arcata Solar Farm. Let’s all sit down.” Bluebeard’s tone was neither welcoming nor inviting. She had just issued an order.

Redbeard cooked espresso using an antique steam-driven machine while Bluebeard stared at the data Eliasz was beaming to her eyepatch. It was the formula for an attention stabilizer that the IPC had acquired for just this purpose, after it failed out of clinical trials. At least 50 percent of the people taking it had developed debilitating migraines that lasted for days. But there was no way to know that from the formula; it had all the appearance of legitimacy.

“You say you got this from PharmPraxis?” Bluebeard asked, her single-eyed gaze taking in both Eliasz and Paladin, who sat at the bonsai table across from her.

Eliasz nodded.

Trying to maintain the illusion that he was mentally damaged, Paladin forced himself to train his front visual sensors on some water molecules traveling through the tree whose body comprised the table, leaning his head close to the grain and microscoping in on it. His other sensors were taking in as much data as he could without tripping any alarms.

“This is very interesting,” she continued, flicking the data to a holo display in front of Blackbeard. “I’m going to have to ask you to stay here while we do more analysis.” She sent a burst of network traffic to Roopa, who appeared several seconds later at the door to the conference room. “Make yourself comfortable,” Bluebeard said to Eliasz. “You can use our gaming system if you want.”

Eliasz gripped Paladin’s arm. “That’s fine, but the bot stays with me.”

Bluebeard shrugged. “No problem.” Then she turned to the tall Federation man who hated Big Pharma. “Youssef, you come with us.”

Roopa loomed above them. When Paladin tuned her perimeter network it was just another unreadable haze of encrypted traffic.

Copyright © 2017 by Annalee Newitz

Order Your Copy

Cascade Failure by L. M. Sagas

Cascade Failure by L. M. Sagas Rubicon by J. S. Dewes

Rubicon by J. S. Dewes When the Sparrow Falls by Neil Sharpson

When the Sparrow Falls by Neil Sharpson Autonomous by Annalee Newitz

Autonomous by Annalee Newitz Exadelic by Jon Evans

Exadelic by Jon Evans by TJ Klune

by TJ Klune

Altered Carbon

Altered Carbon

The Laundry Files series

The Laundry Files series