opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

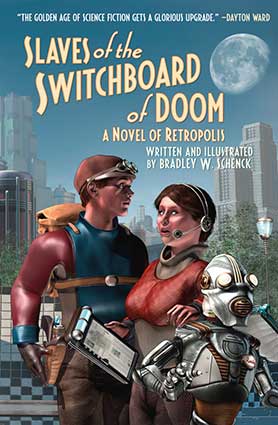

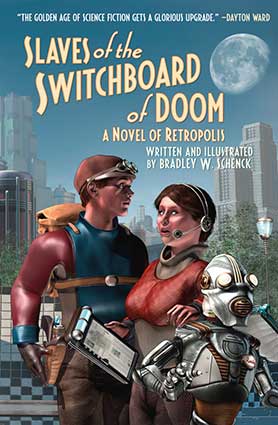

If Fritz Lang’s Metropolis somehow mated with Futurama, their mutant offspring might well be Slaves of the Switchboard of Doom. Inspired by the future imagined in the 1939 World Fair, this hilarious, beautifully illustrated adventure by writer and artist Bradley W. Schenck is utterly unlike anything else in science fiction: a gonzo, totally bonkers, gut-busting look at the World of Tomorrow, populated with dashing, bubble-helmeted heroes, faithful robot sidekicks, mad scientists, plucky rocket engineers, sassy switchboard operators, space pirates, and much, much more—enhanced throughout by two dozen astonishing illustrations.

After a surprise efficiency review, the switchboard operators of Retropolis are replaced by a mysterious system beyond their comprehension. Dash Kent, freelance adventurer and apartment manager, is hired to get to the bottom of it, and discovers that the replacement switchboard is only one element of a plan concocted by an insane civil engineer: a plan so vast that it reaches from Retropolis to the Moon. And no one—not the Space Patrol, nor the Fraternal League of Robotic Persons, nor the mad scientists of Experimental Research District, nor even the priests of the Temple of the Spider God, will know what hit them.

opens in a new windowSlaves of the Switchboard of Doom will become available June 13th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

The Temple of the Spider God

Tuesday, 1:42 PM

The Scarlet Robots of Lemuria had begun to climb the walls of the citadel by the time Dash remembered to check the time. He frowned: he really should have picked a shorter story.

He folded the magazine carefully, stowed it in his back pack, and pulled out his ray pistol.

You have to be cautious when you’re sneaking around on the Moon. Dash had perfected a kind of belly-hop, all toe tips and stomach muscles, that propelled him up to the edge of the ridge in a series of tiny hops, his chest gliding about an inch above the powdered stone. He kept his helmet low. From the ridge he could see right down into the depression in the crater where two priests stood, guarding the Temple of the Spider God.

From Dash’s vantage the entrance was nothing more than a rough square in the grey stone. All the action was inside. Dash stayed low behind the ridge. He’d moored the Actaeon about a quarter mile away, in a new spot—he never used the same one twice—and from here not even the tip of its nose cone could be seen. The priests of the Spider God paced back and forth before the entrance to their Temple with no idea just how much was about to change.

Dash checked the time again.

Right on schedule a powdery plume erupted in the hillside above the Temple. There was no noise, of course, but the two priests felt the rumble underfoot and turned their glassy faceplates toward the explosion. Dash had his ray gun out and was already on the move before they’d finished their turn.

The first priest went down from Dash’s ray blast before he even knew that Dash was there, but the second was smarter: with one hand he swept his spear behind him while drawing his own pistol with the other—all while leaping ten feet straight up—and spotted Dash, who was still twenty feet away. The priest came down with the grace of long practice.

The priest fired off a single beam before the spear came out again to slice an arc of vacuum just in front of Dash’s feet.

Dash hated those spears. You had to either close in and grapple, or dance back out of range; and once he’d gotten out of range of the spear the pistol would start up again, every time. So as soon as the spear swept past, Dash lunged forward, head first. The dome of his space helmet slammed into the priest’s belly and knocked the big man over. Dash landed on top of him, only to find himself staring down the barrel of the priest’s ray gun.

The priest made Dash drop his ray gun and motioned him toward the temple door. As they passed the other guard, the priest toed his midsection. The fallen priest stirred a little. They left him out there, and passed through the open doorway into the Temple’s airlock. As they entered, a hatch descended silently from the lunar rock, sealing them in.

Dash tensed when felt his captor’s hand heavy on his shoulder, but he waited until the chamber had filled with atmosphere. He didn’t flip the switch on his belt until the inner door rolled open.

The electromagnet in Dash’s back pack came alive silently and charged the thousands of hidden threads in his clothing: Dash became a magnet that yanked him down onto the airlock’s grated floor. He braced his feet and let himself fall backward. The priest, still gripping his shoulder, went down beneath him, exactly as planned.

The priest’s spear clattered loose on its lanyard and his ray gun scraped across the floor. From here on out it was purely hand to hand.

Head shots were impossible—neither one of them had removed his helmet. They traded body blows and rolled across the grating, wrestling through the doorway and into the interior of the Temple. Dash got one arm around the priest’s throat. But when he tried to roll on top of the other man he found his magnetized legs had stuck to the grating. Well. That was unexpected.

The big priest knocked him back, smashing Dash’s helmet against the airlock wall. A hairline crack crawled out across the dome right in front of Dash’s eyes. The priest pulled Dash’s head back and slammed it into the wall again, and this time a couple of glass slivers rang on the helmet’s rim.

Dash saw the priest’s face crinkle into a grin and he grinned right back as his fingers curled around the man’s fallen ray gun, on the floor under Dash’s back. His grin stayed where it was: but the priest had a change of heart when Dash brought the gun’s barrel around and pointed it at the man’s face.

From then on, it was back to the plan.

After binding the priest’s wrists and ankles with a couple of ties from his back pack, Dash retrieved his ray gun and tossed the priest’s weapons into a little room off the Temple’s main hallway. The walls were bare and grey with some kind of coating spread over the ancient lava tube to seal it against the vacuum outside. But as plain as the tunnels were, the rooms were furnished comfortably with wooden furniture, as well as plenty of tapestries and pillows. Dash figured that one of these little rooms ought to be the one where they were holding Princess Fedora.

But he was wrong. When he reached the hallway’s end he hadn’t seen a trace of her.

A gong sounded from somewhere farther inside the Temple. He wasn’t sure whether that meant their rituals were ending, or if they were rolling right along—he didn’t even know what went on in there. But he’d rather not be standing there when the priests filed out. Where was the Princess?

Dash walked back past the last few doorways. Hadn’t he seen . . . ?

In the middle of one room’s floor was a circular hatch. It stood conveniently open, with the top of a ladder peeking over the edge. It was like a well . . . but a well on the Moon? He stepped into the room and gave the hatch a long look. You don’t really want to be down there with an open door behind you, do you? But since the room’s door was made of steel, with a doorframe to match, it didn’t take him long to rig his electromagnet up to the thing. The door snapped shut with a muted ring. He tried it. It didn’t budge.

Dash opened his back pack and shuffled through its contents; but after a moment he realized he was only stalling. He steeled himself and went down the ladder.

Dash unfastened his helmet’s seal and pulled it off his head. “Princess Fedora?”

The ladder had ended just above the floor of another, smaller hall. He looked left and right. A narrow groove ran down each side of the tunnel. The grooves looked a little like the tracks for the traveling heat ray the priests had surprised him with last month. Not much of a challenge, really; he located the emitters and wedged them in place. Then he found the pressure plates and deactivated them before he started to explore the hall.

He almost missed the lava pit. Getting careless, he thought.

At the hall’s far end he found a single locked hatch. He rummaged in his back pack for his lockpicks, and after a few minutes’ painstaking work, the door swung open to reveal a small but luxurious stone chamber, draped with tapestries and strewn with carpets and cushions. Dash grinned. Princess Fedora lay draped across the pillows and looked up, bored, to see him standing in the doorway. Like this happened every day.

“Princess Fedora!” He reached out toward her. She spat at him, scratched his arms, darted between his boots, and ran out of the room.

“Mraaow!” she complained. Dash caught her before she got too far. He put one of the pillows in his helmet and after much effort, and a few more scratches, he got her curled up safely inside.

A few minutes later he’d made his way back to the airlock just in time to catch the first priest, now recovered and untying the second. Dash stunned him with another blast from his pistol and helped himself to the priest’s helmet. The second priest glared at him while Dash arranged Princess Fedora in that new, airtight carrier. She seemed sleepy, but he knew better than to think she was finished with him. He pulled the helmet’s seal extra tight.

He looked down at the second priest. “It’s Thorgeir, isn’t it? I’m afraid I’m gonna have to ask you for your helmet, too, seeing as you broke mine.”

Dash knelt to unseal the helmet’s collar. The bound priest endured the removal of his helmet with a fearsome scowl. “We’ll meet again, Dash Kent.”

Dash nodded toward Princess Fedora. “You could always just stop taking them, you know.”

But Thorgeir seemed to be out of conversation, so after donning the priest’s helmet Dash took his leave. For now he was happy to get the Princess back to his rocket, and the two of them back to Earth. He had some chores to take care of.

Tuesday, 9:46 PM

Except for the constant, hushed rhythm of cables unplugged and replugged, the switchboard was always as quiet as a library, especially during the night shift. That persistent sound was one that Nola heard even in her dreams. She was operating for seven Info-Slate owners this evening and that took a great deal of skill, as she hoped the others had noticed.

Three of her clients were Air Safety and Astronautics officers. Nola unplugged the cable for one client’s main pane and switched it, in one swift, fluid motion, to the feed for pilot registrations. Her hand hovered over the connection. She was sure she’d missed something.

Her eyes stayed on that plug even as she swapped the connections for two of her other clients. The ASAA officer had requested a registration search for a vehicle. The type of vehicle in the search was a commercial transport, yet she’d asked for the Private Registry. Nola completed another switch and with deft practice linked the first officer’s sidebar connection to the Commercial Registry. Somewhere over the streets of Retropolis she knew that the officer’s Info-Slate had rung a soft chime.

That should take care of that, Nola thought. Then she forgot all about it while she kept up with the new requests from all seven of the distant Info-Slates.

Between their main panes, sidebars, and message lists Nola’s hands were doing a constant dance when—and this was practically unheard of—her headset buzzed. One of her clients was requesting a voice connection!

Nola slammed the button immediately. Maybe none of the other operators had heard. What had she done wrong?

“Officer da Cunha?” she whispered. “How can I help you?”

A finger tapped her shoulder. Nola blushed. It was Mrs. Broadvine, her supervisor, and she wasn’t alone. Nola breathed into her microphone, “Excuse me, Officer. I’ll be right with you.”

Mrs. Broadvine took the headset and microphone and looked at them with the pinched expression she reserved for things that were not up to her standards. She turned to her companion. “The voice system,” she explained, “is intended for emergency use in cases where the Info-Slate operator has confused a request.” She looked down at Nola. “It is seldom used.”

“May I?” asked the bald man in the hat. Mrs. Broadvine handed him the headset and microphone. He spoke softly for a moment, and then he listened. The constant clicks and pops that rustled up and down the bank of operators seemed full of meaning: dire, hidden meaning. Nola felt sure that every operator on the line was straining to hear the conversation. She could have just died.

The bald man in the hat handed the gear back to Nola. “Quite the opposite, this time,” he informed Mrs. Broadvine. “An officer has just called to thank your operator for correcting her own mistake by providing the correct information, in addition to the information that was requested.”

Mrs. Broadvine, wincing, was wrestling with Nola’s cables; her eyes kept darting to each of the seven clients’ panels. It must have been years since she’d worked as an operator herself. The operators on either side sat impeccably straight, eyes fixed on the switchboard, and yet somehow gave all of their attention to the drama that was playing out at Nola’s station.

The man in the hat looked down at Nola from what seemed to be a very great height. “Do you make that kind of correction often?” he asked.

Nola turned away from Mrs. Broadvine’s ordeal to offer the bald man a slight smile. “Oh, sometimes I do,” she said. “It all depends on how familiar I am with that kind of request. I mean, I know the registration indices pretty well; if it was a zoning inquiry, though, one of the other girls would probably know better than me.”

He was writing in a little notebook. “So . . . it comes down to your individual experience, then.” He frowned. “I don’t suppose there’s a . . . a clearing house, a repository, of all that information?”

Nola shook her head. “There are just so many possible inquiries. . . .”

The bald man snapped his notebook shut. “I see. No one operator is like another, and each one has her own strengths and weaknesses. So for every advantage it’s likely that there’s an equal disadvantage.”

Nola wasn’t quite sure what answer she could make to that, but it seemed like none was needed: the bald man’s attention had already gone elsewhere. Nola rescued her clients and Mrs. Broadvine from one another, and by the time she’d gotten caught up she was alone again. She had completely forgotten the officer on the line.

“Miss Gardner?” came the voice over the headset. “I didn’t mean to get you in trouble. I just wanted to say thanks.”

Nola checked Officer da Cunha’s panel and read the Registry connections she’d made. “I don’t think that was trouble, really, but I’m not quite sure what it was. Or even who.”

“He said he was Howard Pitt, that engineer from the Transit Authority. You know, the Tube Man.”

The name sounded familiar. “Are you all set with your inquiry? I couldn’t help but notice it was one of those old Actaeon rockets—the interplanetary ones. So of course it wouldn’t be a private citizen.”

“That’s the odd thing,” said Officer da Cunha. “It is a commercial registration, but the owner seems to be an individual named Kent. Kelvin Kent. He describes his business as ‘Freelance Adventurer.’ But his registration’s current, anyway. I was sure surprised to see that big old rocket touching down in the city.”

Nola glanced at the panel while her fingers swapped cables and flipped switches for her other clients. “Oh, yes, I see. That’s unusual.”

Officer da Cunha thanked her again and hung up. Nola’s hands had never slowed in their dance over the switchboard. Freelance Adventurer, she thought. That sounds like an interesting line of work.

Tuesday, 10:09 PM

The work wasn’t without its challenges, Pitt was the first to admit; but it was still just a sideshow. The main event, now, that was what really required his attention. He strode down the steps of the Info-Slate Switching Station with the kind of concentrated purpose that came to him by nature. A tall man made even taller by his signature hat, Howard Pitt somehow projected the idea that he’d just returned from, say, the Grand Canyon, after having bridged it, or from the Serengeti after installing an aqueduct that would change its history forever. Howard Pitt radiated purpose and accomplishment.

It was a quality that wasn’t shared by many of his colleagues. Although the engineers of Retropolis were undoubtedly accomplished and didn’t lack for purpose, they were typically a bit myopic, and either rather thin or prodigiously stout, and they usually began their conversations with an “Ermm . . . ,” a “Hmmm . . . ,” or sometimes, an—

“Ahh, excuse me, sir.”

Pitt paused and, by habit, looked down at the spectacled, rather thin person who’d spoken. Pitt shifted to rest his hand on the holstered slide rule at his hip. “It’s Perkins, isn’t it.”

It wasn’t a question; more like an assertion that happily for Perkins was true, since otherwise he might have had to offer a correction.

The contrast between the two men was remarkable. Abner Perkins was an experienced engineer with the Retropolis Transit Authority, typical of the breed described above and, in fact, although he did not know it, practically its archetype: from the ink stains on his breast pocket to the socks that he would discover, later that evening, didn’t match after all. A world that could create two such different engineers might be capable of anything.

“Yes, sir. It’s Perkins. I had some questions about the specifications for the Tube system.”

“You will understand,” said Pitt, “that I’ve resigned from the Transit Authority as of yesterday. From now on I have to be considered a consultant.” His hand idly stroked his holstered slide rule. “You can request a meeting with me during business hours, under the terms of my contract.”

“Well, yes, sir, of course I can. But I knew you’d be making another visit to the Slate Switchboard, and, erm, I happened to be near here, and . . . well, I . . . didn’t think there’d be any difficulty.”

Pitt stared down at Perkins impassively while the smaller man stared in a completely different way at the pavement. “No harm done,” Pitt said at last.

“Oh, good.” Perkins pulled out a sheaf of papers and held them in front of him. “I’ve been trying to understand the overage in the air pressures you’ve required in the Transport Tubes. They, ah, they seem to be roughly five hundred per cent of the air pressure that the system, well, that it actually needs. It’s such a significant difference that, well, I just . . .”

“Safety precaution,” said Pitt. “If there should be any failure of the system there must be sufficient air pressure remaining to deliver those passengers still in the system to its nearest exit. If you calculate the greatest distance between exits and the air pressure that’s necessary, I think you’ll find that everything is in order.”

“Yes!” Perkins seemed to be on familiar ground. “I did that, of course, but I noticed that far less pressure would be required if we, ah, if we were to add two more exits on that route. It’s, uhm, it’s just so much longer than any of the others. . . .”

Pitt began to take long, emphatic steps down the street. “Naturally,” he called back, “you could add those additional stations later on, and then reduce the required air pressure. At your convenience.”

Perkins pulled another sheet from his stack and waved it. “Sir? Mister Pitt, sir? There’s also the question of the inertrium overage. . . .”

It was too late, though. Abner Perkins stood alone, waving his sheets of specifications, and felt somehow . . . insignificant.

Perkins scanned the manifests again. The Tube system had just required so very much inertrium, and he couldn’t imagine where it had all gone. Maybe if he understood the design better. . . .

A robot, laden with packages, bumped into Perkins and apologized. Abner turned to see the entire city that he had (not unusually, for Abner) been ignoring while he considered his own thoughts.

The city of Retropolis extended for many miles in every direction, including the vertical one. For that reason no one could really take it all in. But Abner knew it all so well that his mind filled in the gaps behind the many-storied towers, the lit glass domes, the lively monorail terminals, and the canopies of the trees that, huddling in the streets, cast their cool shadows along pedestrian walkways.

Buildings like machines and machines like buildings crowded the bases of the towers. The great skyscrapers themselves receded, level by level, so that sunlight could reach the parkways between them, and that always made Abner think of elongated ziggurats with glass-paneled sides. Pedestrian skyways bristled from the sides of the towers to bridge the streets.

Utility robots moved smoothly along the walkways, cleaning litter and sweeping leaves out of the way of the people—both human and mechanical—who were rushing about their errands. There was the occasional collision, like the one Abner had just suffered, but overall there was more than enough room for everybody. And in the higher reaches—where the skyscrapers did indeed scrape the sky or, anyway, its clouds—personal rockets with open cockpits swept along in their own unimpeded arcs under the watchful supervision of Air Safety and Astronautics officers. The ASAA rockets passed overhead in a regular grid that gave them a good view of all those pedestrians and rocket pilots below; and, above even the ASAA rockets, buoyant inertrium airships floated along their stately routes, giving tourists and the more unhurried citizens of Retropolis the best possible view of the city.

Abner took a deep, contented breath. He loved the city, every time he remembered that it was there.

But just now his own business worried him. He squinted at the papers in his hands. He was sure these things would all make perfect sense once he’d had the chance to think about them properly.

Tuesday, 10:51 PM

Rusty exited the Tube Pod with more equilibrium than most people; but then most people were not mechanical, and so they had a tendency to be unsteady. The new system was seeing a lot of use despite the fact that people on the way out of a Transport Pod would often need a moment or two to wait for the world to stop spinning.

Rusty felt this might explain why some human people enjoyed the Tube Pods. He hadn’t made up his mind just yet.

One advantage to the Tubes, in Rusty’s opinion, was that only a single Pod could arrive at any one station at a time. A minute or two would always separate them; this was convenient if you knew you were being followed. Rusty set a brisk pace down the street in order to get as far as possible from the Pod Station in the next one to two minutes.

His pursuers didn’t worry Rusty. He knew who they were; he knew what they wanted; he knew they weren’t going to learn what they wanted to know; and, when it came right down to it, he was used to them. But if he was going to be followed then he knew that he was expected to be evasive and in this, as in most things, Rusty did his best to oblige.

He turned into an alley.

Not a dark, dirty, and uncomfortable alley, full of garbage and persons of questionable intent: this was Retropolis, after all. This alley was more or less what an alley ought to be: broad and clean, leading decisively between the buildings on either side with plenty of room for two vehicles to pass each other, even though ground vehicles were practically extinct. It was, normally, well lit.

Tonight it was surprisingly dark.

Several lights that should have illuminated the alley had been broken. Right around the middle of its length the alley actually looked a bit threatening, which is to say that you couldn’t tell what it looked like.

Rusty paused.

Most people, whether they were human or mechanical, would have known this was unusual. But one of the many jobs Rusty had tried through the years was in the Light Maintenance Division of the Public Works Department. So unlike most people Rusty knew that these lights had been checked, cleaned, and polished earlier that day, just as they were on every day; Rusty knew that this damage was very recent. He also knew that actual damage to the lights was so rare that a single broken street light could become a kind of legend, a story that Light Maintenance workers would gather to tell on dark, stormy nights when all the lamps had been polished, but they still weren’t ready to go home; a story that would begin: “It was on a night much like this one, a night when the golden streetlights pulsed bravely against the eternal darkness that brooded around them, their polished caps and bezels glinting brightly in the gloom; a night when no one who could help it was to be seen abroad, and strange things roamed in the empty streets . . .”

Rusty had always enjoyed those stories.

As he stood quietly at the edge of the lighted end of the alley, Rusty felt—just a little bit—that he had become a part of that ancient legend of The Night The Lamp Went Out. He looked behind him at the well-lit, empty end of the alley, and then he turned with precision to walk right into the darkness, where a moment later he stumbled over something on the ground.

He bent over it, the lamps of his eyes glowing, and he saw something horrible.

Two minutes later, several men came along the street and looked down the darkened alley. No one was there.

Copyright © 2017 by Bradley W. Schenck

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

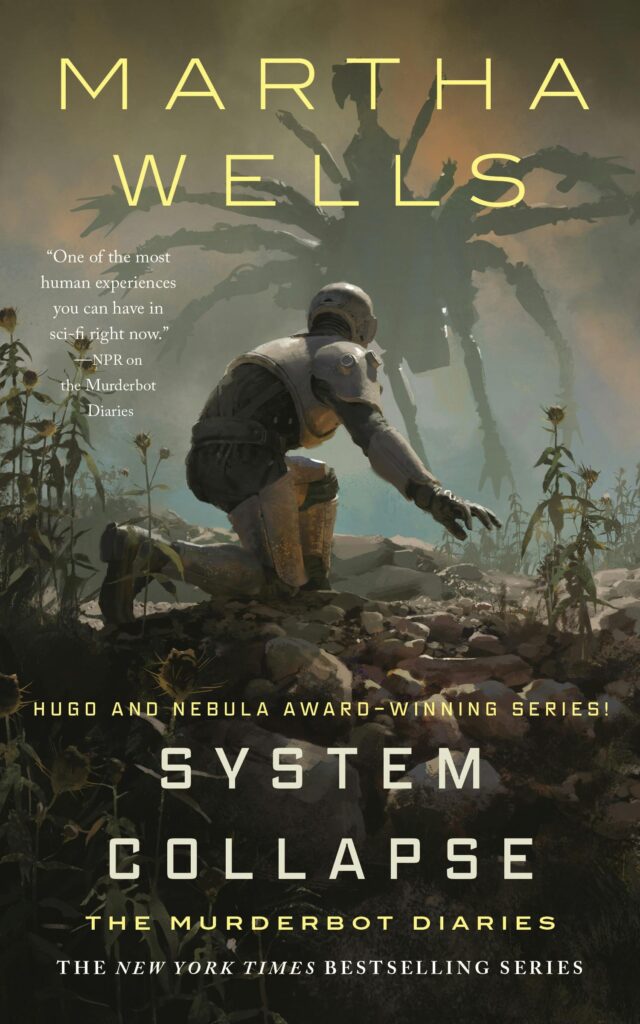

opens in a new windowSystem Collapse by Martha Wells

opens in a new windowSystem Collapse by Martha Wells Service Model by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Service Model by Adrian Tchaikovsky opens in a new windowSlaves of the Switchboard of Doom by Bradley W. Schenck

opens in a new windowSlaves of the Switchboard of Doom by Bradley W. Schenck opens in a new windowIn the Lives of Puppets by TJ Klune

opens in a new windowIn the Lives of Puppets by TJ Klune opens in a new windowThe Jinn-Bot of Shantiport by Samit Basu

opens in a new windowThe Jinn-Bot of Shantiport by Samit Basu opens in a new windowThe Archive Undying by Emma Mieko Candon

opens in a new windowThe Archive Undying by Emma Mieko Candon