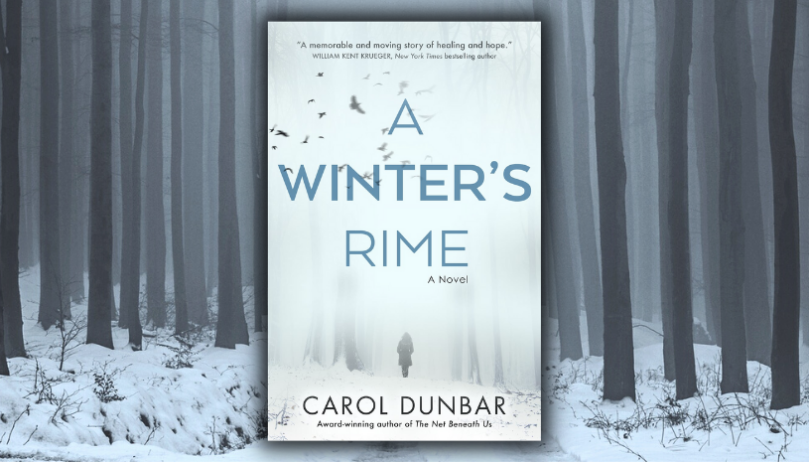

A harrowing and emotional novel set in rural Wisconsin—A Winter’s Rime explores the impact of generational trauma, and one woman’s journey to find peace and healing from the violence of her past.

A harrowing and emotional novel set in rural Wisconsin—A Winter’s Rime explores the impact of generational trauma, and one woman’s journey to find peace and healing from the violence of her past.

Mallory Moe is a twenty-five-year-old veteran Army mechanic, living with her girlfriend, Andrea, and working overnights at a gas station store while figuring out what’s next. Andrea’s off-grid cabin provides a perfect sanctuary for Mallory, a synesthete with a hypersensitivity to sound that can trigger flashbacks from her childhood.

The getaway that’s largely abandoned during the off season starts out idyllic, until Andrea’s once-loving behavior turns controlling and abusive, and Mallory once again finds herself not wanting to go home. After a particularly disturbing altercation, Mallory escapes into the subzero night and stumbles into Shay, a teenage girl, injured and asking for help. But it isn’t long before she realizes that Shay isn’t the only one who needs saving.

A story about sisterhood and second chances, A Winter’s Rime looks to nature to find what it can teach us about bearing hardship and expanding our capacity to forgive—not just others, but ourselves.

A Winter’s Rime will be available on September 12th, 2023. Please enjoy the following excerpt!

CHAPTER ONE

During the winter of her twenty-fifth year, Mallory Moe lived in a cabin in the woods with a woman named Andrea and worked overnights at a gas station store. Her shifts at the Speed Stop rotated— 1400 until midnight, 2200 until dawn, or 0500 until the middle of the afternoon. She either left in the dark or returned in the dark to walk the dog around the frozen lake. She never knew what day of the week it was, whether morning or afternoon, day or night. She only knew that she needed to avoid being home.

Mallory had never been in a romantic relationship with another woman before, and it had been working out fine, until the government shutdown meant that Andrea was always around. It was a small cabin, a dark winter.

Mallory clipped the leash to the dog and pulled on her gloves, but Andrea had one of those fiddly leashes—a protracting reel with buttons and levers.

“You already walked her this morning,” Andrea said, and Mallory jumped.

“Yeah.” She’d thought that Andrea was on the couch, watching television. “But I’ll just take her out again.”

“She doesn’t need to go out again.”

Baily’s little toenails clicked on the linoleum.

“I think she does,” Mallory said. “I don’t mind.” She bungled through the back door, coat unzipped, hat jammed on her head, the protracting wheel spinning out as Baily zipped down the decking stairs.

When they’d first met, Mallory had been subletting a bedroom in her coworker’s house in the bar district of Sterling, the blue-collar town on the Wisconsin side of the bridge. It had been the easiest thing, requiring the least amount of effort. But city buses rumbled along, the air smelled of cigarettes, and once, after working all night, Mallory had come home to see a woman peeing on the sidewalk. Her situation now was much better. The only place that made any sense to her was the woods. She needed to live someplace remote, without people and noise, where she could figure out her life. But ever since the government shutdown Andrea had been glued to the TV that blasted sound throughout the house—people gunned down in synagogues, in schools; stories of climate change, the end of life as we know it; bombs exploding in the streets.

Mallory pulled up her hood and stuffed her gloved hands in the pockets of her coat. They headed out down the middle of Riley Ridge Road, paved and plowed, but snow-covered and streaked with sand. From behind them, out on the back deck, the drone of the generator faded. She felt loosed from the center of herself, her muscles corded and tight. Above her a nearly whole moon rose in a sky amply pierced by starlight.

Baily trotted out front, a mystery terrier the size of a fuzzy slipper, with a red sweater and two ears alert on the top of her head. Her claws crepitated on the snowpack, collar jingling in the icy air. Usually they went about half a mile, until the road branched off and met up with another one. Normally, before the shutdown, Mallory would turn them around at that point to go back to the cabin, where it was warm. But lately, she’d been taking that branch because it looped around the lake, and sometimes, she lingered in front of the house of Landon James.

Landon, the only other full-time resident that winter at Mire Lake, split his own firewood and drove a banana-yellow truck. His house sat by the side of the road that looped around the lake, more than a mile and a half away. Once a week he came into the Speed Stop for his generator fuel and often the two of them would talk.

Mallory slowed and held out her hand. The last of a snowfall meandered down. Flakes tumbling out from a clear night sky glinted uncertainly, directionless, now that the source that had created them had moved on.

The last time Mallory had seen her sister and mom, they’d had a fight. That had been four years ago, the month before Mallory shipped out to Kuwait. She’d served a total of seven years in the army, joining at the age of eighteen, and that June she had come home. No one had been there. Her sister Laurel was living with their mom in Upstate New York and attending a private university. Her dad was someplace in the desert looking for Jesus. Mallory had been back six months—no, seven months now, she realized—but she still hadn’t talked to any of them.

She veered to the right, taking the loop around the lake. Her boots creaked across the snowpack. She was not going to be one of those people who blamed every bad thing that happened to them on their parents. It wasn’t their fault she didn’t feel safe. It wasn’t their fault she could never afford a place like this on her own. And anyway, things with Andrea weren’t that bad.

“Once upon a time in the deepest darkest woods,” her mother used to say, when she and her sister were young, and they would squeal with delight, beg her to tell them the deepest darkest bedtime stories. But those stories were just for fun. The people in them didn’t act upon their deepest darkest thoughts, things always worked out, and nobody got hurt. They worried about things, what they feared they or others might do. But those things were never done. So, what scared them, then, what they only ever truly feared, was in the deepest darkest parts of their minds. It didn’t get let out because it was never real.

Or it was never real because it didn’t get let out.

That winter during her twenty-fifth year, something had been let out. Mallory could feel it in her gut, a disturbance that wouldn’t go away. She heard about it from the news stories on the television that relentlessly played. People were acting on their darkest thoughts and doing things that, previously, they would never have done.

Mallory didn’t know how to talk to Andrea about what was going on between them. She didn’t know how to explain it, other than to say that it was her fault. Something was wrong with her—a character defect, a moral weakness. She wasn’t just afraid of what Andrea would do; Mallory had begun to fear who she was whenever the two of them were alone. Images flashed through her head—memories, arguments, loud percussive sounds, and, more recently, her fight with Andrea.

They came fast around the bend, Baily leading the way, with the frozen lake to their left and the light of Landon’s cabin straight ahead. Snow piled thick on his roof, his generator silent. A column of chimney smoke rose straight into the frigid air.

The brash, throaty bark of a dog broke into the night. Mallory startled and jumped, flinging out both hands and losing the leash. She dipped and picked it up, scooping little Baily into her arms and bringing her up to her chest.

“Shh shh, girl, it’s all right,” Mallory said, whispering into the dog’s ear. It was Landon’s German shepherd barking outside, a large dog that was never on a leash, and although she didn’t think he would hurt Baily, Mallory didn’t want her to be afraid. The little dog shivered and whimpered in her arms. The sound of the barking whipcracked through the night.

“Odin! Get back here! Odin!” Landon called from inside his house, the light from his open back door splashing into the woods. He was a hundred feet away, but in the cold stillness it sounded as though he were right there. Mallory lifted her face. “That’s a good boy,” he said to his dog. A hundred points of touch tingled in the soft skin under Mallory’s chin. “Back inside now, old friend. There you go. That’s a good dog.”

Tingles rippling under her jaw as if feathers stroked her there, and her face softened, her eyes closed. The air seemed to bloom with the scent of fresh bread, and it made her want to cry, this feeling. Landon wasn’t baking bread—unless of course he was. But she always got the feeling, as she called it, whenever she heard his voice. It was just the way her brain worked. Some voices didn’t affect her— she felt nothing and didn’t know why. Other voices came on so strong they activated multiple senses at once, like the wires of her brain had gotten crossed somehow. They had a name for it: auditory-tactile synesthesia. Sound touched her skin.

Her grandfather had been the one who explained it to her. He had synesthesia, too, after he came back from the war. She had his name, Mallory. German for “war counselor,” French for “unlucky one.”

From behind Landon’s house came the soft thump of a closing door. Mallory opened her eyes. With Landon, it was more than just the feeling. It was the way he said things, the kindness in his voice. She had never heard a man talk the way he did.

It had stopped snowing.

Baily wriggled in her arms and Mallory set her back down.

“What is it, Baily Bales?”

The little dog stood alert and questioning at the end of her leash.

“Did that scare you?” Mallory asked, removing a glove. “Are you cold? We should go.” The lever on the protracting reel had gotten stuck, and the little dog watched, then yanked the leash, slipping it from Mallory’s grip as she wickedly ran off.

“You little shit!” Mallory hissed under her breath. The clunky protracting reel bounced out along the white tongue of the road and Mallory launched into a run, her hood falling back, the ends of her bloodred hair bouncing under a black beanie hat.

The loop ended when it met back up with Riley Ridge Road, and Mallory could no longer see Baily. She heard the little dog barking, the splinters of sound echoing in the night. Mallory jogged to the left instead of going right, which would have taken them back to the cabin. Up ahead in the moonlight, the silhouette of Baily quivered.

Car parts scattered across the road caught Mallory’s attention first. Particles of iridescence shimmered over the broken bits—reflector lights, plastic bumper shards. “You are a bad dog.” Mallory dipped and swiped up the leash, breathing hard, lungs burning from the cold. The breath vapors rising from her mouth had formed ice in her lashes and brows. Baily yipped and hopped, hoarfrost clinging to the fur around her face.

A large brown mass lay across the road. A stillborn silence hung over the scene. Mallory never saw other cars out this far, out past the lake, and she’d never been on this section of Riley Ridge Road. This area was remote, Mire Lake not connected to the grid. Was somebody else staying there? Maybe for the weekend?

She wondered this, but it was only a fleeting thought. The deer was still breathing. A doe gurgling blood, eyes two glimmering slits. The muscle of her tongue hung limp and helpless from the side of her mouth, the fumes of her breath weakly white and forming tiny fronds of ice. Her legs were tangled below her body, disfigured with planks of protruding bone, the hooves shiny as summer plums.

A jolt fired through Mallory’s body.

The memory played involuntarily in her head, a memory from childhood, and she could hear him and smell him like he was there. “Come on then,” Dad said, home from Iraq for the holidays. “You want to go hunting so bad, wake up your sister up and get dressed.” He moved through the dark of the house with a headlamp strapped to his head, his body lean and fit. She always admired the decisiveness of his movements, coiled and crisp. Whenever he did something, he did it right, and if he said he’d do something, it got done.

Laurel was eight then, which made Mallory twelve, although both girls were the same height. Bits of cereal still floated in their bowls as they hurried out to their father’s waiting truck, rifles slung across their backs, exhaust curdling in the night.

They parked on the side of a county road and trekked out to the deer blind. Two sisters bundled together in a predawn stillness, crouched in a cheek-to-stock weld. Mallory wore an eye patch, a present from her father, to help align her sight—she never could wink or close just one eye. A slow-motion snow fell, the flakes tiny and iridescent in the limpid air. A quiet so still, she could hear the snow land with faint tick-ticks on the scraps of dried leaves.

A deer stepped timidly into the clearing.

Slender ears twitched and turned, she stepped forward, and in that movement, as if by secret signal, two smaller deer followed, creeping out from the duff. A mother and her young.

One for each of us, her father’s look said.

The crack of gunshot. The blood invading snow. Mallory hadn’t even known she was screaming until her sister punched her in the chest. “You ruined it, Mallory!” she said. “Why do you always have to ruin everything!”

Back on Riley Ridge Road, Mallory climbed over the crest of snow plowed in the ditch to tie the little dog to a tree. Taking a knee close behind the deer, she removed a glove, and sliding the knife from her boot, she thrust it quick and deep into the throat, wrenching it crosswise until two fountains of blood drained and light faded from the doe’s eyes. Then, placing a thumb on the smooth plank of the glabella, she offered up an acknowledgment to the spirit passing, the way her friend Ottara had taught her when they served together in Kuwait.

She had cried all weekend after that hunt with her dad, not coming out of her room, staying in bed. She hadn’t understood it, what hunting required. She’d begged to go because she wanted to be part of things, to have an experience with her dad, but it had devastated her, the thought of those two motherless deer. They’d tracked that mother doe for hours, her dad’s bullet missing the lungs because she had cried and always, she cried. She was too sensitive, everyone said.

Wiping the blade clean, Mallory replaced her glove and stood. Breath vapors fumed around her face and she could smell herself— fight or flight, the scent of fear. It was an odor that had followed her from childhood, a smell that was real and pungent and able— somehow—to escape the mask of deodorant. She kicked at the car parts, knocking them off the side of the road. Her breath came shallow and fast, and saliva coated her tongue with the viscosity of blood.

“Tell her to quit being a pussy.” She’d heard them arguing about her, later that night, her dad’s voice coming through the thin bedroom walls. “She’s weak,” he said. “No mental fortitude.” Venison was good meat, and deer were rats on legs.

A front bumper, the socket of a headlight, and what looked like the gray cover to a side fender—those she picked up and hauled off, tossing them into the woods.

The deer lay with her head facing the trees. Mallory lifted the back legs and pulled. The joints popped, part of the body stuck to the road. She yanked harder, ripping the fur as she tore it from the frozen ground. Walking backwards and averting her eyes, she dragged the deer, leaving behind a slick smear, the slosh and gurgle of fluids and the rank smell. She pulled it onto the snow piled in the ditch off the side of the road and left it there to get picked at by the crows.

Click below to pre-order your copy of A Winter’s Rime, available 9.12.23!