1

“The food was too rich, for one thing. So were the guests. The dinner party was a dud long before the Nazis got involved.”

I looked over at Edith Head, a blur of motion behind her sketch pad. “But you’ve heard my Chaperau saga before. More than once.”

“True, dear, but your account is so entertaining.”

“You can’t buffalo me. This is about Lorna Whitcomb’s column this morning. Are Paramount stars involved?”

“One hears rumors, so one seeks facts. You were there, eyewitness to history. Humor me. Don’t mind my sketching. I can draw and listen at the same time. It’s the essence of the job.”

A trace of paint fumes perfumed Edith’s office in the Wardrobe department at Paramount Pictures, olfactory proof she had finally arrived. The suite had formerly been home to Edith’s mentor Travis Banton. She had assumed Banton’s responsibilities in March when the studio opted not to renew the brilliant but bibulous costume designer’s contract. Paramount hadn’t been in a hurry to bestow his title or office on Edith, though, the formal announcement coming after she’d been doing his job for months. Her first official act as Paramount’s lead designer had been to have her new domain repainted, the walls now a soft gray. “Like a French salon,” she’d said. “A muted palette places the focus on the actress, where it should be. Besides, if I don’t change something in here no one will take me seriously.”

Edith’s personal transformation was more dramatic. She’d abandoned her bobbed hairstyle in favor of bangs with a chignon at the back. The new coiffure was a touch severe when paired with Edith’s owlish spectacles, but it suited her businesslike demeanor perfectly. I’d complimented her on it when I’d entered the office that morning. She’d waved me off. “Copied from Anna May Wong. A new look for the new position. With my unfortunate forehead, I’m afraid the options are rather limited. Then I remembered how striking Miss Wong’s hair looked when she returned to the studio to make Dangerous to Know. I haven’t decided if I’m going to keep it.”

I owed my presence at the infamous dinner party, along with a bounty of other opportunities, to my friendship with Edith. If she wanted to hear the story again, then she’d get the full roadshow rendition. My goal: uncork a spellbinder to make her set aside her sketch pad.

“The entire trip happened at the last minute. That’s how it is with Addison.” Meaning Addison Rice, the retired industrialist who had inexplicably seen fit to give me a job. “His wife Maude was about to sail for Europe with a companion, but the grim news from the Continent was giving her second thoughts. Addison decided to see her off in New York, and asked me to come along.”

“Because it’s your hometown,” Edith said.

“I think it was more he wanted company on the trip back. It was a whirlwind jaunt. We waved our handkerchiefs at the Queen Mary, leaving me enough time to race out to Flushing and visit my uncle Danny and aunt Joyce.”

“How are they?”

“Dying to meet you. I gave you some buildup. While we were in Gasparino’s Luncheonette, Addison ran into a familiar face on Fifth Avenue.”

“Albert Chaperau. The producer.”

“Who’d been haunting Addison’s parties, looking to meet people. So thrilled was he to see his bosom pal that he finagled us invites to a Park Avenue dinner. Instead of going to a picture at Radio City Music Hall, Addison and I turned up like foundlings at the home of a state supreme court justice.”

I described our hosts. Judge Edgar Lauer, a bluff man in his late sixties, wore the authoritative air of someone who handed down verdicts even when he wasn’t on the bench. His fiftyish wife Elma made a more vivid impression, thanks to the wardrobe she’d chosen for the occasion. “That gown,” I whispered, still thunderstruck lo these six weeks later.

Edith looked up from her sketch pad, but her pencil kept moving. I hadn’t won her over yet.

“Picture a floor-length sheath of white silk jersey,” I said. “With a gargantuan royal-blue bow covering most of the bodice. The points of which unfortunately emphasized Mrs. Lauer’s sagging jawline.”

“It sounds quite audacious.”

“That’s one word for it. It wasn’t designed for a matron entertaining at home. It was meant to be worn in some Parisian boîte by a woman half her age.”

“Someone like you?” Edith said with one of her patented closed-lipped smiles. “I don’t believe you ever told me what you wore that evening.”

“I made do.”

“With what, exactly?”

“You’ve seen the dress. Ice-blue satin with a square neckline and short matching jacket.”

“For a formal dinner?” Edith raised an eyebrow. Now I prayed she’d continue sketching, not wanting to earn her undivided attention this way.

“Didn’t I say it was a whirlwind jaunt? That was the best outfit I brought.”

“You are the social secretary for one of the most prominent men in Los Angeles, and you weren’t prepared for the possibility of a formal dinner? A floor-length dress, evening shoes, and a wrap would have taken the same amount of space.”

“Not the way I pack.” It didn’t seem the time to point out how far I’d come in the year since I’d been a failed actress turned shopgirl without a pair of evening shoes to my name. “It’s not as if Addison had a tuxedo. He wore blue serge!”

Edith closed her eyes with tremendous forbearance. “Go on.”

“The Lauers throw more sedate affairs than Addison’s. Their guests hail from politics, industry and the Social Register. Albert Chaperau was completely out of place. You’ve seen his picture in the newspapers? Heavyset fellow, head like a salt block? All these staid sorts and there’s Chaperau, filling the air with ideas like so many soap bubbles, not caring virtually all of them were destined to pop and leave only slickness behind.”

“A taste of Los Angeles,” Edith said.

“Truth be told, I enjoyed having him there for that very reason. He was just back from Europe and had a whole slate of projects he’d discussed abroad, including an American version of his film Mayerling.”

“I know it was a huge success, considering it’s in French,” Edith said. “But how does he propose to get that ending out of the Breen Office alive?”

“That was my first question. Actually, my first question was, ‘Can Charles Boyer star in it again?’ Chaperau said the murder-suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf and his young love was a matter of Austrian history, and any American retelling would be true to the record.”

Edith clucked dubiously, just as I had.

“Dinner was served,” I went on, “the first course a deathly white cream of mushroom soup. I was seated next to Serge Rubinstein, a financier who’d cornered the market in coarseness. Addison mentioned he’d just sent his wife off on a tour of the Continent. Chaperau asked where she was visiting. ‘I wouldn’t put faith in maps much longer,’ he says. ‘Those poor souls in the Sudetenland didn’t think they were in Germany.’ Everyone at the table had recently been in Europe and had a dire report to contribute. Judge Lauer believed the Austrian Anschluss and the Sudeten crisis had only whetted Hitler’s aggression. Mrs. Lauer said their summer shopping had been spoiled by the mood of despair. All the while Addison is turning paler than his soup.”

“The poor man,” Edith said. “He must have thought he’d dispatched his wife into near-certain doom.”

“For his sake I wanted the war talk to stop, so I went to my can’t-miss subject. Who should play Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind?

“Still stumping for Joan Bennett?”

“She’s only the perfect choice. Admit it. But sadly, no one took the bait, because Chaperau insisted on polishing his credentials. He announced he was recently named attaché for the government of Nicaragua. Which came as a surprise, because I thought he was French. Rubinstein asked what a banana republic needed with a picture maker, and Chaperau held forth on films as a universal export, shaping ideas around the globe. He claimed Hitler himself knew this, and it was why the exodus of talent from the UFA studios in Berlin distressed him. Then Judge Lauer weighed in. ‘Hitler’s a madman who must be stopped. We’re fooling ourselves if we think otherwise.’”

Edith made a quiet sound of satisfaction. Whether at the judge’s politics or her own still-in-progress sketch, I couldn’t tell. Time for bold methods. Time for me to act.

I stood and began staggering around the room. “Throughout the conversation, Rosa the maid had been refilling glasses. Now she stops and slams her tray onto the sideboard.” I performed the scene, reeling into Edith’s desk. My Rosa had a clubfoot, my hammy instincts getting the better of me. “Mrs. Lauer asked if she was all right. But Rosa, her face bright red, was not.” I gave my next words a Teutonic twist. “‘I am happy to work in your home, Mrs. Lauer. But first and foremost, I am a true German. I love Adolf Hitler. And I will not abide anyone speaking this way about the Führer. If these insults do not cease at once, I will stop serving. The choice is yours.’”

Edith finally put down her pencil and gaped at me. I had her captivated at last. Game, set, and match, Frost.

“It was so quiet after Rosa’s outburst, I was certain everyone in the dining room could hear my heart racing. Then Rubinstein asks, ‘Is Park Avenue part of the Sudetenland, too?’ Judge Lauer, an old hand at pronouncing sentences, stands up. ‘Then you may go at once, Rosa.’ The maid storms out one door, Mrs. Lauer scurries out another in tears. I went after her. She was still apologizing to me when Rosa appeared, wearing a coat as black as a nun’s habit. She looked at Mrs. Lauer and said, ‘Madam. There remains the matter of references.’”

Edith hooted with laughter. “Rosa certainly has her nerve. Marvelous accent, by the way. You sound like Marlene Dietrich.”

“Addison’s is even better. We’ve been telling this story a lot. Rosa’s request hit Mrs. Lauer like a bracer. She drew herself up and asked Rosa if her sister still worked as a retainer for the former Grand Duchess Marie of Russia. ‘Not only will I not provide you with a reference,’ she proclaimed, ‘but perhaps I will telephone the grand duchess and let her know what kind of blood runs in your family.’ To which Rosa replied, ‘Only good German blood, madam, something the grand duchess already knows. Much as you know there are telephone calls I, too, can make.’ With that, Rosa moved past us and out into the night. Mrs. Lauer and I linked arms and returned to our soup.”

“Remarkable,” Edith said. “But of course it wasn’t over.”

“Oh, no. Throwing Manhattan’s most awkward dinner party since the Gilded Age wasn’t enough. The next day, Addison and I belatedly made it to Radio City to see The Mad Miss Manton.”

“Ah, Stanwyck.” Edith sighed, with me happily taking a second chorus. Barbara Stanwyck was one of our favorite people.

“While the picture played, the Lauers’ world collapsed. Rosa Weber, freshly unemployed, marched into the U.S. Customs offices and spilled every bean in her possession. The Lauers, she told the authorities, were guilty of smuggling, along with Albert Chaperau. It seems Mrs. Lauer cleaned out various ateliers on her summer excursion to Paris. Chaperau then transported her purchases in his luggage, which bypassed customs inspection owing to his dubious diplomatic status as a representative of Nicaragua. Consequently, Mrs. Lauer avoided paying import duties on the clothes. A few days later, Albert Chaperau—right name Shapiro—was taken into custody at his suite at the Pierre. He was in white tie and tails at the time, having been at the Stork Club until four in the morning. I say if you have to be arrested, that’s the way to do it.”

Edith nodded in agreement.

“Customs men also raided the Lauers’ apartment, hauling cases of couture away. By then Addison and I were back in Los Angeles. A Customs agent, gruff man name of Higgins, drove out to ask us about the dinner party. He said last year the Lauers hadn’t declared a load of fancy clothes and jewelry, costing them more than ten thousand dollars in duties and fines. Agent Higgins made it clear the Customs Service was not in the second-chance business. He also said Mrs. Lauer had hied herself to a sanitarium. I felt for her. She didn’t strike me as particularly black-hearted or criminal. Just another rich woman insulated from the real world. Plus she agreed Joan Bennett would make a splendid Scarlett O’Hara.”

“I almost sympathize with Mrs. Lauer for going along with Mr. Chaperau’s proposal,” Edith said. “I had no idea I was supposed to pay import duties on the gowns I purchased when the studio sent me to Paris this summer. There I am on the dock, suddenly owing a fortune! A man from the New York office had to come down and set matters right. Mrs. Lauer’s outré dinner party gown had been smuggled in by Mr. Chaperau, I take it.”

“It’s now being held as evidence. Your turn to spin a yarn, Edith. What have you heard about Chaperau’s West Coast operations?”

“Only that he appears to have made his services available to at least one figure at Paramount. The place is in an uproar. An encore of your account of the dinner seemed in order.”

Typical Edith, gathering intelligence on behalf of the studio where she spent every waking moment. I pressed her for the suspect star’s name knowing she’d keep mum. Such was her loyalty. Were Paramount under siege, tiny Edith would hoist a pike and defend the Bronson Gate.

Bested, I asked, “What were you sketching away madly on?”

“Dorothy Lamour’s costumes for the new Jack Benny picture.”

“Speaking of Jack—”

Edith huffed out a sigh. “I haven’t forgotten my promise to get you into an early screening of Artists and Models Abroad.” In addition to starring my favorite comedian Jack Benny and my personal Scarlett O’Hara Joan Bennett, Artists and Models Abroad boasted a fashion show sequence already being touted in fan magazines: a parade of gowns from the finest designers in Paris. Schiaparelli and Lanvin, Maggy Rouff and Alix. I was champing at the bit for an advance look, and my eagerness undoubtedly chafed Edith given her costumes were being upstaged by the haute couture.

Edith’s receptionist knocked on the door. “Pardon me, Miss Head, your next appointment is here.”

Marlene Dietrich coasted into the office, crooked smile first. She wore a pale green daytime suit with a subtle checkered pattern and slightly flared skirt. The matching emerald veil on her low-crowned hat did extraordinary favors for eyes that required no help.

Edith and Dietrich embraced, the actress bending to kiss the diminutive designer on both cheeks. Edith introduced me, my knees knocking at the prospect that Dietrich had somehow heard my cut-rate imitation of her. “But Lillian and I have already met,” Dietrich said, her accent an ermine wrap around every syllable. I sounded nothing like her. “At a party hosted by your lovely employer Mr. Rice. Perhaps you remember?”

“How could I forget? You played the musical saw.” The image of Dietrich flicking her dress to one side, tucking the handle of the blade between those impossible legs, remained a high point of my Hollywood sojourn.

Dietrich crossed those legs now as she sat down and took immediate possession of the room. I rose, preparing to leave the ladies alone.

“Thank you for arranging this opportunity to consult with your esteemed guest,” Dietrich said.

I cocked an expectant eye toward the door only to discover that Dietrich gaze again aimed squarely at me. Apparently, I was the esteemed guest.

What had Edith walked me into?

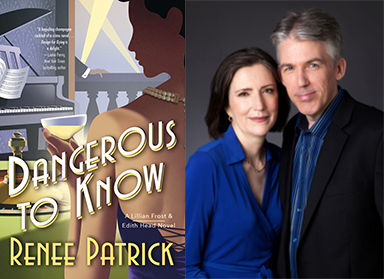

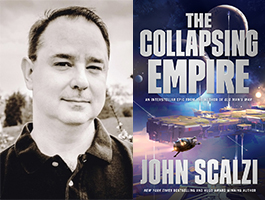

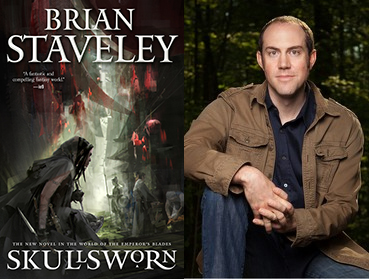

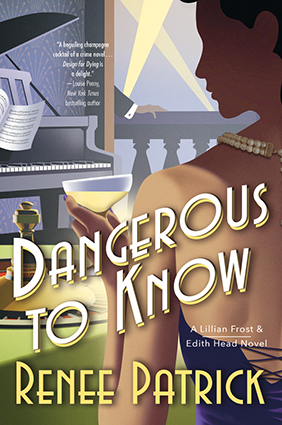

Naturally, we at Forge don’t want to be left out. We’ve scoured our list to find the perfect gal-pal mystery books to celebrate this esteemed holiday, and we’ve hit on a winning pair: opens in a new windowDesign for Dying and its sequel, opens in a new windowDangerous to Know, by Renee Patrick.

Naturally, we at Forge don’t want to be left out. We’ve scoured our list to find the perfect gal-pal mystery books to celebrate this esteemed holiday, and we’ve hit on a winning pair: opens in a new windowDesign for Dying and its sequel, opens in a new windowDangerous to Know, by Renee Patrick. Their adventures continue in Dangerous to Know, where Edith and Lillian deal with career challenges, see the war clouds gathering over Europe, run into the likes of Jack Benny and Marlene Dietrich, and unravel intrigue extending from Paramount’s Bronson Gate to FDR’s Oval Office. All while dressed to the nines, of course―this is Hollywood, after all.

Their adventures continue in Dangerous to Know, where Edith and Lillian deal with career challenges, see the war clouds gathering over Europe, run into the likes of Jack Benny and Marlene Dietrich, and unravel intrigue extending from Paramount’s Bronson Gate to FDR’s Oval Office. All while dressed to the nines, of course―this is Hollywood, after all.