opens in a new window

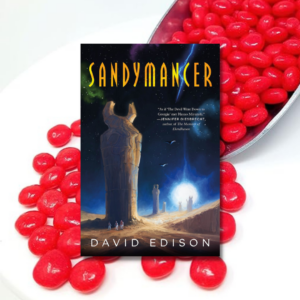

A wild girl with sand magic in her bones and a mad god who is trying to fix the world he broke come together in SANDYMANCER, a genre-warping mashup of weird fantasy and hard science fiction.

All Caralee Vinnet has ever known is dust. Her whole world is made up of the stuff; water is the most precious thing in the cosmos. A privileged few control what elements remain. But the world was not always a dust bowl and the green is not all lost.

Caralee has a secret—she has magic in her bones and can draw up power from the sand beneath her feet to do her bidding. But when she does she winds up summoning a monster: the former god-king who broke the world 800 years ago and has stolen the body of her best friend.

Caralee will risk the whole world to take back what she’s lost. If her new companion doesn’t kill her first.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of opens in a new windowSandymancer by David Edison, on sale 9/19/23

Chapter 1

The day the monster stole Caralee’s future started out as dull and shiny as any other—with children and young folk scattered around the sandy circle that served as a gathering place for the families of the nameless village. In this half-ruined amphitheater, they took their lessons from a woman dressed in undyed linen, her head, neck, and chin wrapped about with a threadbare gorget. Later, most would return to the cable fields with their elders, or stay within the village for piecework and other chores.

Caralee sat cross-legged on her favorite schooling seat, smiling at the crack in the sky. An age ago, her seat was a column; now only the plinth remained, scoured smooth by centuries of sandstorms into a seat-shaped groove that cradled Caralee’s bottom just so. The stone fit her far better than her burlap shmata ever would.

Marm-marm pointed at the fractured sky. The morning sun rose above the horizon, gold and brilliant, but the sky, she’d taught them, was far too dark. Once, it had been a much lighter blue, which was a color Caralee found difficult to imagine so far above and in such quantity. Wouldn’t that be awfully bright? She’d learned that when the sky had been light blue, the stars had been invisible during the day. That, too, she struggled to imagine.

The crack in the sky looked like frozen lightning, jagged and forking. At noon, when the sun passed behind it, you could see that the crack was four or five times longer than the sun.

Other students lazed or whispered, but Caralee leaned forward, elbows on her knees, eager to answer Marm-marm’s questions and ask her own.

“Who can tell me about the sky?” Marm-marm shielded her eyes from the sun with one hand while pointing with the other, tracing the lines over her head. “Is it broken? Why is it broken? How is it broken? How can we tell that it’s broken?” Marm-marm always asked too many questions at once, which was Caralee’s favorite thing about the woman. Caralee never said that to her face. That would clam up Marm-marm’s curious mouth, which was the last thing Caralee wanted on any day.

“Mphh!” Fanny Sweatvasser grunted through a mouthful of her own hair, then wicked her wet curls out from between her teeth so she could offer up one of her habitually bizarre answers. “A mightily infestatation of metallicky creatures”—Fanny pronounced the word cree-aht-choors, which gave Caralee a headache— “crawled from their nests—their nests are the stars—and are a-spinning their bea-ut-iful cobbyweb across the sky.” Fanny hunched her shoulders and gazed at the sky with delighted horror. “They want to catch the sun and steal away its light until it’s as wee as a star. Then they’ll hatch more cre-a-tures from that star and lay eggs in our brainpans with their rustipated penises.” Fanny spread her lips in what would have been a smile if it hadn’t been as flat and haunted as the wasteland horizon. “That, Marm-marm, is my answer.”

“Oh, Fanny.” Marm-marm looked like she’d swallowed some vomit. “Can anyone offer a less, hmm—a different answer?”

“Hey, Fanny,” sassed Diddit Flowm, bouncing his knee. “If your stupid star-critters are gonna hatch from the sun, then why’re they gonna put eggs in our heads? That makes no sense.”

His friends smirked, and Caralee laughed to herself. For Diddit, that was a truly massive amount of insight.

“I asked for an answer, Diddit Flowm.” Marm-marm scolded the boy without much enthusiasm. “A little help, Caralee?”

Caralee wanted to point out that, as usual, Fanny had taken a tiny grain of truth—tiny, mind you—and ran away with it, returning with something so ridiculous that the truth could no longer be found. But Marm-marm had asked her for answers, and Caralee loved answers.

“Well, Mag says that the crack in the sky used to be a little thing.” Caralee didn’t have facts, so she began with observations. Caralee had been raised by Mag, alongside her grandson, Joe Dunes, and was the wisest person Caralee knew, even if she didn’t have as much book learning as Marm-marm. “Mag also says that the sky was lighter during the day, although I don’t see how that would work. I mean, how would we—”

“Yes, Caralee, thank you.” Marm-marm always called on Caralee, but never let her finish. “When Old Mag Dunes was wee, that-uppa-there crack was wee, too, and the day sky shined bright blue.”

The other students oohed at the thought of such a pretty, bygone sky, but Caralee liked the crack below the sun. It was interesting, a commodity in short supply, here at the fringes of the wasteland. She loved the sky, with its stars peeking through their darkly colored veils.

“And,” Marm-marm pressed her advantage. “We couldn’t see the stars whenever the sun came out. Back then, the sky only darkened to shades of indigo near dawn and dusk.”

“What’s a findigo?” asked a boy with wild hair and one eye that was always staring at his nostrils.

“Anyone?” Marm-marm asked the seated students, propped up on stone blocks and other remainders of the Land of the Vine. “What, asks Marmot Kleyn, is findigo?” She scanned the faces of her students, most of whom were still sleepy, and cared little for learning. Caralee waved her hand high, but Marm-marm gave the rest of the class a few seconds to catch up, if any were so inclined. They were not. “Yes, Caralee?” She braced her hands on her hips and stretched her weary back. “You can put your arm down, girl. You know full well that you’ve no competition here.”

Don’t call me “girl” is what Caralee almost said, but thought better of it. She grabbed her arm like a separate thing and dragged it into her lap as if it had a mind to shoot up and start waving again.

“Yes, Marm. For starters, ‘findigo’ ent anything, but indigo, was a plant— and it’s a color, too. It sits right between violet and blue, on the rainybow wheel.” Which we learned last year and there are only seven scatting colors to remember, she thought but also did not say.

“That’s right. Now, can anyone tell me why a crack in the sky and a darkening sky might be connected?”

“Well,” Fanny began, and Caralee suspected that she was not about to answer Marm-marm’s question. “First of all, the rainybow wheel was invented by the droods to hide the fact that they keep all the green in one super-secreted underground well, excepted for water, it’s got green. All the greens.”

“No, Fanny, just no.” Marm-marm pressed her hands to the sides of her head, fidgeting with the wrapped burlap gorget that hid her neck and cheeks. “If there are still droods in the world, they may not be singing fruit from treebones anymore, but they have most certainly not stolen all the green and hidden it in an underground well.”

Fanny narrowed her eyes, now convinced that Marm-marm was part of the plot.

“And the rainybow wheel is real,” Caralee added. “Marm-marm has a picture of it in her learning-book. You’ve seen it, Fanny.”

“But have I?”

“You have!” Caralee was aware that she was shouting. “You’ve seen it! You’ve seen the rainybow wheel, and green and indigo are both scatting on it!” Fanny was a fool, but Caralee wasn’t cruel enough to say so out loud.

“You’re on the rainybow wheel, chucklehead.” A sandy-haired older youth— not one of the students—entered the open space and strolled up to Marm-marm as if she were a girl at a dance. Caralee wilted.

“Hullo, Marm,” he said, angling for charm and not quite succeeding.

“Good day to you, Joe Dunes.” Marm-marm forgave him with a twitching smile, and Caralee wondered what it would feel like to have Joe Dunes aim his charm at her and fail. Sands, he could even win! Caralee wouldn’t mind.

Not that she’d ever say that aloud, either.

Joe Dunes rubbed the hay-bright fuzz that had covered his big square jaw for almost two years now. Caralee knew exactly how many days it’d been since she’d noticed he’d begun to beard.

Joe crossed his thick arms and smirked his square-jawed smirk. He winked at Caralee, who blushed, though she tried her best to keep the blood from rushing to her face.

Dunderhead, she thought. Joe’d never had the luxury of sitting and learning, busy as he’d been helping Mag do the work of towing the processed cable plant products for trade.

Joe kicked a rock and hopped when he crunched his big toe. Was there ever an opportunity to stub a toe, that her Joe passed up? He lacked any trace of physical grace, but his heart was as big and warm as his hands. Caralee shook her head and hid a smile.

“You’re here for—” Marm-marm started to say.

“Caralee, get your—”

“Of course you are—”

“—bottom off that rock and follow me.” Joe stuck out his tongue at her. Joe’s tongue wasn’t exactly charm, but it’d do. “Come on. We better be in the cart before the burden-critters get hungry.”

Which was ridiculous. The burden-critters were the sweetest things ever, and Caralee would let them kiss her hand for whole minutes at a time. Their soft proboscises would suckle her fists or slobber-up her face with kisses. Joe Dunes was the chucklehead, and Caralee said so.

Marm-marm cleared her throat.

“Those sweet critters eat scat all day, Joe Dunes, and if they did get hungry, they’d go after you,” Caralee sassed him right back. She tried to make a habit of sassing Joe back—at least when people were around. “You don’t scare me.”

“Aww, don’t you ever snack, Caralee?” Joe kicked the dirt and stubbed his other big toe. “Ouch. They love to crunch on a head so full of chuckle,” he said, and mimed cracking open her head and sucking out her brains with a slurp. “Better not tempt fate, huh?”

“Atu would never!” Caralee protested, despite the sheer idiocy of the thought of the gentle burden-critters—with their furry antennae and meek nature— snacking on anything more than a juicy pile of shit. “And Oti’s too shy.”

“Please continue this dance outside my classroom.” Marm-marm ushered them out of the disintegrating amphitheater, which was already outside, but Caralee upheld her policy of not sassing Marm-marm. “As it disturbs anyone unfortunate to be trapped anywhere near the two of you.” Marm-marm massaged her temples, then rolled her eyes with the hint of a smile. “Caralee, you are excused for work duty.”

The teacher turned her gorget-wrapped head to the student body and began picking on one of the sleepier boys, wrestling with their ignorance until someone cried out:

“Dust trail!”

Caralee whipped her head behind her, looking toward the entrance to the unnamed village. A banner of dust flew from the deep wasteland that lay to the northwest, and it stopped just before the crusty remains of the village walls.

“What’s that?” Joe asked out loud, though how was she to know?

Caralee tasted the air. Something smelled different than usual. Prettier.

“You smell that, Joe?”

“Wossit?” He sniffed, nose twitching like a dust hare. “That smoke?”

“Naw, Joe, that’s incense.” Joe wasn’t keen enough to argue the difference. “You know what that means!”

“Patchfolk? But they ent due for another month.”

The class erupted in excitement, and after a few useless flaps of her arms, Marm-marm surrendered. The students scattered—racing one another the extremely short distance to the sad cairns that served as the gates of the village.

“It’s Patchfolk, for sure.” Caralee smiled.

Twice a year, the nomad caravans emerged from the deep wasteland, where icy dust storms and hungry quicksand ruled. They came to trade and to maintain the relationships upon which both groups relied. The wasteland was more dangerous than anyplace in the whole world, and both the travelers and the settled folk benefited from trading information about what hardships they’d faced, and where—what routes were safe, and which were dangerous. Who’d disappeared and where.

The Patchfolk and the villagers were like estranged cousins, a family born not from any common culture but out of need. Folk elsewhere rightly feared the ever-spreading wasteland that would one day consume every corner of the world, but the villagers and the Patchfolk, they knew the wasteland. They survived on its feeble offerings and lived in its clouded, shifting glare.

“What if they got a sandymancer with ’em?” Caralee heard the whine in her voice, but didn’t care.

Often the Patchfolk traveled with a sandymancer or two—wizards from the far northeast, who commanded the elements and told stories of the old world, when the wet green Vine snaked across the land, instead of the mummified fingers of cable plant that had to be hacked apart with machetes and milled three times before it approached edible. The sandymancers told one particular story over and over again, as if on a mission, and although Caralee had heard it a dozen times, she never lost interest—largely because the candle-backed wizards never finished the tale.

“Yeah, yeah, what if . . .” Joe knew how this conversation would go. “Mag’s waiting on us, Caralee.”

“Patchfolk, Joe!” She tugged on his sleeve. “Mag can wait. She’ll understand. You know she will.” She very likely would not, but Mag could sit on it.

Joe rolled his eyes. “You skitter off to watch those sandymancers whine about how Ol’ Sonnyvine wrecked the world every time one rolls into town. Do they ever tell you anything new?”

“Not yet.” Caralee climbed back onto her comfortable plinth and crossed her arms behind her head. “But this time, I’m gonna learn the end of the story.”

Joe and Marm-marm both sighed. The three of them were alone in the amphitheater, which was quiet now, but would soon be busier than before.

“All-a-right, chucklehead, but when Gran starts spittin’, the blame’s on you. Deal?”

“Deal!” Mag would most definitely start spitting, but Caralee didn’t mind taking the blame—not if it got her what she wanted. If she couldn’t see the world, Caralee would learn about it, spit or no spit. “Now sit down, dunderhead, and grab a good seat before the class comes back and brings the whole village with them.”

Copyright © 2023 from David Edison

opens in a new windowThe Fragile Threads of Power & Sour Patch Kids Watermelon

opens in a new windowThe Fragile Threads of Power & Sour Patch Kids Watermelon opens in a new windowTraitor of Redwinter & Zombie Skittles

opens in a new windowTraitor of Redwinter & Zombie Skittles  opens in a new windowBookshops & Bonedust & Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup

opens in a new windowBookshops & Bonedust & Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup  opens in a new windowDevil’s Gun & Disco’s

opens in a new windowDevil’s Gun & Disco’s opens in a new windowThe Doors of Midnight & Giant Gummy Shark

opens in a new windowThe Doors of Midnight & Giant Gummy Shark  opens in a new windowStarter Villain & Sour Patch Kids (Original)

opens in a new windowStarter Villain & Sour Patch Kids (Original) opens in a new windowExadelic & Monster Energy

opens in a new windowExadelic & Monster Energy  opens in a new windowSandymancer & Red Hots

opens in a new windowSandymancer & Red Hots  opens in a new windowA Sorceress Comes to Call & Witch’s Brew KitKats

opens in a new windowA Sorceress Comes to Call & Witch’s Brew KitKats opens in a new windowBlood of the Old Kings & Orange Starbursts

opens in a new windowBlood of the Old Kings & Orange Starbursts  opens in a new windowStarling House & Blackberry Cobbler Candy Corn

opens in a new windowStarling House & Blackberry Cobbler Candy Corn opens in a new windowUsurpation & Black Licorice

opens in a new windowUsurpation & Black Licorice  opens in a new windowWind and Truth & Blow Pops

opens in a new windowWind and Truth & Blow Pops