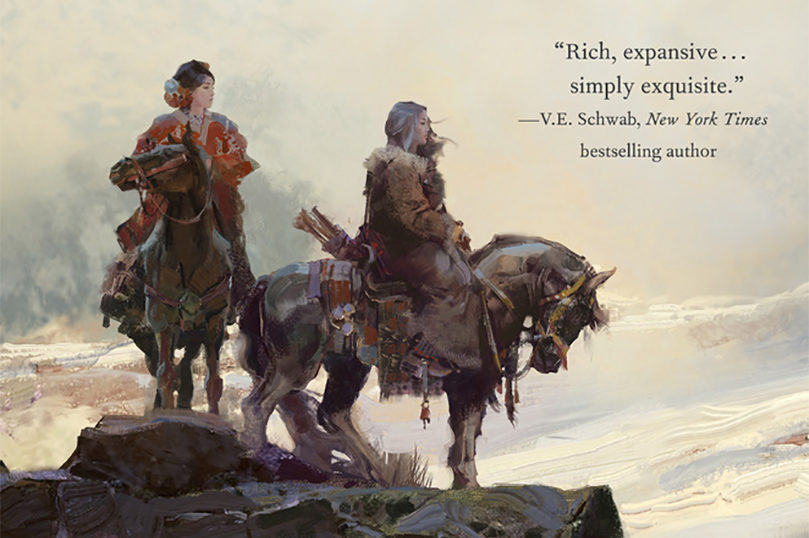

opens in a new window Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an interview with K. Arsenault Rivera on language barriers, outsider heroes, and why epic fantasy loves prophecies so much. Her first novel, opens in a new windowThe Tiger’s Daughter, is the story of a pair of exceptional women who are destined to face the evil forces rising out of myth. Read the first chapter here!

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an interview with K. Arsenault Rivera on language barriers, outsider heroes, and why epic fantasy loves prophecies so much. Her first novel, opens in a new windowThe Tiger’s Daughter, is the story of a pair of exceptional women who are destined to face the evil forces rising out of myth. Read the first chapter here!

The frame narrative of The Tiger’s Daughter involves an epistolary unfurling leading to the main conflict. Does the format of handwritten letters hold any particular significance to you?

There’s just something so Romantic about long letters! I read a lot of Victorian lit in the year or two before I wrote The Tiger’s Daughter, and I think the most obvious bleed through is in the epistolary structure. Letter-writing in those novels was always something swoon-worthy and grand, and I wanted to capture that feeling between Shefali and Shizuka—especially given how shy Shefali normally is. The letter allows us to really see into her head, and to see Shizuka through her eyes.

How does the native language barrier and learned exchange between Shefali and Shizuka reflect their characterization? What made you decide to go that route, from a plot-based angle? Did it pose a particular challenge concerning plot structure or did it act as a guide?

Shefali’s inability to read Hokkaran reflects how she feels about Hokkaro as a whole: she understands what they’re saying but not how or why they’re saying it. That she spends so much time within the Empire proper is only for Shizuka’s sake; it’s not a place that will ever fully accept her. In a way, Shefali’s known that since she figured out she’d never be able to read Hokkaran.

Shizuka, on the other hand, has great talent with calligraphy from a very young age. She learns the simple Qorin letters easily enough but never bothers to learn the language itself. Of course, learning to speak the language would mean floundering in front of native speakers and opening herself up to mockery—so it’s not something that interests her. I don’t think that’s a conscious thought she has, but it’s there all the same. Actually trying at things is as foreign to her as the Qorin—but if she bothered, she might find a warmer welcome than she thinks.

Another important point is that most people in the Empire at least understand Hokkaran even if they can’t speak it, whereas Hokkarans only bother learning their own language. Sort of like how English is the presumed language of the Western world, but English speakers get uppity when wandering into a neighborhood that doesn’t cater to them.

Though O Shizuka and Shefali (and their mothers) are incredibly close, both are outsiders within their respective communities–communities that also happen to be at odds with each other. How does that dichotomy resonate with you?

I think that when you’re writing a hero, most of the time they’re an outcast in one way or another. Heroes are (usually, but not always) exceptional people, after all.

For me the interesting contrast is between the girls and their mothers in this regard: Burqila and O-Shizuru both made the conscious decision to break with their communities. Burqila murdered her own brothers to seize power and strike back at the Hokkarans; O-Shizuru decided to put her prized bloodline to use as a pleasure house guard. Both women eventually settle into mundane lives, and both women want the same for their girls.

But the girls didn’t get to make those choices. O-Shizuka is born into a life of politics and caution when she really wants to do is duel people all day and spoon Shefali all night. Shefali’s got to rule the Qorin some day, and she doesn’t seem to care about that as much as she probably should. By breaking with tradition, Burqila and O-Shizuru provided their daughters with much more stable, safe lives, and yet neither daughter wants to take advantage.

What was the process of creating these incredibly complex and strong relationships while integrating the cultural and societal conflict the characters go through as individuals?

The characters of The Tiger’s Daughter came before the setting. I always knew that Shizuka would be a headstrong firebrand, and I always knew that Shefali was her much quieter counterpart. While pantsing my way through the first draft of the novel I kept the characters at the forefront and let them react to the world around them. Shefali can’t quite make sense of Hokkaran society—and so she cannot read the language. Shizuru lived a violent life, and so she wants the opposite for her daughter, no matter what Shizuka actually wants for herself. Burqila married Oshiro Yuichi as part of a peace treaty—so of course she doesn’t care much for her Hokkaran raised son.

There seems to be a great emphasis on destiny, a predetermination of belonging to a certain path or person. I’m curious about your feelings on the permanence or self-fulfilling nature of prophecies.

Every fantasy fan loves a good prophecy, and I’m no exception to this. They’re a lot like magic tricks, I think, in that you know what’s coming but still get that tingly sense of awe when the inevitable occurs. Like a good magic trick, though, it’s all in the delivery and the execution.

Let’s talk weapons. O Shizuka’s, the duelist, weapon of choice is a sword. Shefali’s a bow and arrow. In what ways do these weapons reflect each characters personalities?

Shizuka is as brash and overconfident as she is actually talented. Her decision to use a sword in a world where, for safety’s sake, most people use polearms or bows and arrows, reflects that. She doesn’t mind getting in close because she doesn’t really believe she’ll be hurt. And of course there’s the family history aspect of it. Shizuka is, again, a product of old Hokkaro—and she’s using a weapon from a time that isn’t quite relevant anymore. Who wants to duel when there’s demons coming through the northern border?

That ties into Shefali’s bow and arrow well. She made it herself, as her mother and family made their bows themselves. To the Qorin a bow and arrow are more than a weapon—they’re important tools on the harsh steppes, and more important now that food is getting harder to come by. Shefali uses a bow because she has always used a bow—and because she knows it’d be foolish to attack a demon head on. (Not that her good sense stops her whenever Shizuka needs rescuing).

What are your writing rituals/how do you set out to write? Any procrastination tips?

Full-screen is your friend! It’s so much easier to tab over to Discord or Chrome when you can see them blinking on your taskbar. I mean, even full-screened, you can always hit alt-tab—but I find that out of sight is out of mind when it comes to distractions.

Curated playlists also help a lot (my best friend Rena is kind of a playlist god). Certain songs just make me want to write now when I hear them, even if they’re not on the playlist itself.

Persistence and discipline are the most important things. You don’t have to write every day if that doesn’t suit your needs, but I think you should have a plan for when you’re going to write at least.

Shefali’s culture prides themselves on their connections with nature and particularly their alliances with their steeds. If you could pick an animal to go into battle with, would you choose horses or eagles?

I’d choose an eagle. No one wants to ride a horse through NYC traffic, and eagles are just much cooler as mounts, even if heights terrify me a little. We’ve all got to overcome our fears somehow, right? Knowing my history with my tabletop mounts, though, I’d completely forget I even owned an eagle within a week.

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Follow K. Arsenault Rivera on opens in a new windowTwitter and on opens in a new windowher website.