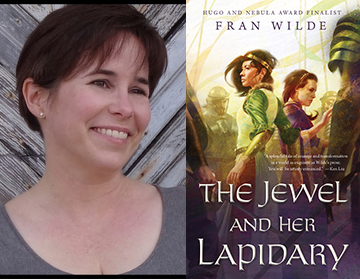

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from Updraft, the first in a series set in a city made out of bone and perched high in the air, where people soar through the skies. The next book in the series, Horizon, will be available September 26th.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from Updraft, the first in a series set in a city made out of bone and perched high in the air, where people soar through the skies. The next book in the series, Horizon, will be available September 26th.

Welcome to a world of wind and bone, songs and silence, betrayal and courage.

Kirit Densira cannot wait to pass her wingtest and begin flying as a trader by her mother’s side, being in service to her beloved home tower and exploring the skies beyond. When Kirit inadvertently breaks Tower Law, the city’s secretive governing body, the Singers, demand that she become one of them instead. In an attempt to save her family from greater censure, Kirit must give up her dreams to throw herself into the dangerous training at the Spire, the tallest, most forbidding tower, deep at the heart of the City.

As she grows in knowledge and power, she starts to uncover the depths of Spire secrets. Kirit begins to doubt her world and its unassailable Laws, setting in motion a chain of events that will lead to a haunting choice, and may well change the city forever—if it isn’t destroyed outright.

1

DENSIRA

My mother selected her wings as early morning light reached through our balcony shutters. She moved between the shadows, calm and deliberate, while downtower neighbors slept behind their barricades. She pushed her arms into the woven harness. Turned her back to me so that I could cinch the straps tight against her shoulders.

When two bone horns sounded low and loud from Mondarath, the tower nearest ours, she stiffened. I paused as well, trying to see through the shutters’ holes. She urged me on while she trained her eyes on the sky.

“No time to hesitate, Kirit,” she said. She meant no time to be afraid.

On a morning like this, fear was a blue sky emptied of birds. It was the smell of cooking trapped in closed towers, of smoke looking for ways out. It was an ache in the back of the eyes from searching the distance, and a weight in the stomach as old as our city.

Today Ezarit Densira would fly into that empty sky—first to the east, then southwest.

I grabbed the buckle on her left shoulder, then put the full weight of my body into securing the strap. She grunted softly in approval.

“Turn a little, so I can see the buckles better,” I said. She took two steps sideways. I could see through the shutters while I worked.

Across a gap of sky, Mondarath’s guards braved the morning. Their wings edged with glass and locked for fighting, they leapt from the tower. One shouted and pointed.

A predator moved there, nearly invisible—a shimmer among exploding gardens. Nets momentarily wrapped two thick, sky-colored tentacles. The skymouth shook free and disappeared. Wails built in its wake. Mondarath was under attack.

The guards dove to meet it, the sun dazzling their wings. The air roiled and sheared. Pieces of brown rope netting and red banners fell to the clouds far below. The guards drew their bows and gave chase, trying to kill what they could not see.

“Oh, Mondarath,” Ezarit whispered. “They never mind the signs.”

The besieged tower rose almost as tall as ours, sun-bleached white against the blue morning. Since Lith fell, Mondarath marked the city’s northern edge. Beyond its tiers, sky stretched uninterrupted to the horizon.

A squall broke hard against the tower, threatening a loose shutter. Then the balcony’s planters toppled and the circling guards scattered. One guard, the slowest, jerked to a halt in the air and flew, impossibly, backwards. His leg yanked high, flipping his body as it went, until he hung upside down in the air. He flailed for his quiver, spilling arrows, as the sky opened below him, red and wet and filled with glass teeth. The air blurred as slick, invisible limbs tore away his brown silk wings, then lowered what the monster wanted into its mouth.

By the time his scream reached us, the guard had disappeared from the sky.

My own mouth went dry as dust.

How to help them? My first duty was to my tower, Densira. To the Laws. But what if we were under attack? My mother in peril? What if no one would help then? My heart hammered questions. What would it be like to open our shutters, leap into the sky, and join this fight? To go against Laws?

“Kirit! Turn away.” Ezarit yanked my hand from the shutters. She stood beside me and sang the Law, Fortify:

Tower by tower, secure yourselves,

Except in city’s dire need.

She had added the second half of the Law to remind me why she flew today. Dire need.

She’d fought for the right to help the city beyond her own tower, her own quadrant. Someday, I would do the same.

Until then, there was need here too. I could not turn away.

The guards circled Mondarath, less one man. The air cleared. The horns stopped for now, but the three nearest towers—Wirra, Densira, and Viit—kept their occupied tiers sealed.

Ezarit’s hand gripped the latch for our own shutters. “Come on,” she whispered. I hurried to tighten the straps at her right shoulder, though I knew she didn’t mean me. Her escort was delayed.

She would still fly today.

Six towers in the southeast stricken with a coughing illness needed medicines from the north and west. Ezarit had to trade for the last ingredients and make the delivery before Allmoons, or many more would die.

The buckling done, she reached for her panniers and handed them to me.

Elna, my mother’s friend from downtower, bustled in the kitchen, making tea. After the first migration warnings, Mother had asked her to come uptower, for safety’s sake—both Elna’s and mine, though I no longer needed minding.

Elna’s son, Nat, had surprised us by helping her climb the fiber ladders that stretched from the top of the tower to the last occupied tier. Elna was pale and huffing as she finally cleared the balcony. When she came inside, I saw why Nat had come. Elna’s left eye had a cloud in it—a skyblindness.

“We have better shutters,” Ezarit had said. “And are farther from the clouds. Staying higher will be safer for them.”

A mouth could appear anywhere, but she was right. Higher was safer, and on Densira, we were now highest of all.

At the far side of our quarters, Nat kept an eye on the open sky. He’d pulled his sleeping mat from behind a screen and knelt, peering between shutters, using my scope. When I finished helping my mother, I would take over that duty.

I began to strap Ezarit’s panniers around her hips. The baskets on their gimbaled supports would roll with her, no matter how the wind shifted.

“You don’t have to go,” I said as I knelt at her side. I knew what her reply would be. I said my part anyway. We had a ritual. Skymouths and klaxons or not.

“I will be well escorted.” Her voice was steady. “The west doesn’t care for the north’s troubles, or the south’s. They want their tea and their silks for Allmoons and will trade their honey to the highest bidder. I can’t stand by while the south suffers, not when I’ve worked so hard to negotiate the cure.”

It was more than that, I knew.

She tested the weight of a pannier. The silk rustled, and the smell of dried tea filled the room. She’d stripped the bags of their decorative beads. Her cloak and her dark braids hung unadorned. She lacked the sparkle that trader Ezarit Densira was known for.

Another horn sounded, past Wirra, to the west.

“See?” She turned to me. Took my hand, which was nearly the same size as hers. “The skymouths take the east. I fly west. I will return before Allmoons, in time for your wingtest.”

Elna, her face pale as a moon, crossed the room. She carried a bowl of steaming tea to my mother. “For your strength today, Risen,” she said, bowing carefully in the traditional greeting of lowtower to high.

My mother accepted the tea and the greeting with a smile. She’d raised her family to the top of Densira through her daring trades. She had earned the greeting. It wasn’t always so, when she and Elna were young downtower mothers. But now Ezarit was famous for her skills, both bartering and flying. She’d even petitioned the Spire successfully once. In return, we had the luxury of quarters to ourselves, but that only lasted as long as she kept the trade flowing.

As long as she could avoid the skymouths today.

Once I passed my wingtest, I could become her apprentice. I would fly by her side, and we’d fight the dangers of the city together. I would learn to negotiate as she did. I’d fly in times of dire need while others hid behind their shutters.

“The escort is coming,” Nat announced. He stood; he was much taller than me now. His black hair curled wildly around his head, and his brown eyes squinted through the scope once more.

Ezarit walked across the room, her silk-wrapped feet swishing over the solid bone floor. She put her hand on Nat’s shoulder and looked out. Over her shoulders, between the point of her furled wings and through the shutters, I saw a flight of guards circle Mondarath, searching out more predators. They yelled and blew handheld horns, trying to scare skymouths away with noise and their arrows. That rarely worked, but they had to try.

Closer to us, a green-winged guard soared between the towers, an arrow nocked, eyes searching the sky. The guards atop Densira called out a greeting to him as he landed on our balcony.

I retightened one of Ezarit’s straps, jostling her tea. She looked at me, eyebrows raised.

“Elna doesn’t need to watch me,” I finally said. “I’m fine by myself. I’ll check in with the aunts. Keep the balcony shuttered.”

She reached into her pannier and handed me a stone fruit. Her gold eyes softened with worry. “Soon.” The fruit felt cold in my hand. “I need to know you are all safe. I can’t fly without knowing. You’ll be free to choose your path soon enough.”

After the wingtest. Until then, I was a dependent, bound by her rules, not just tower strictures and city Laws.

“Let me come out to watch you go, then. I’ll use the scope. I won’t fly.”

She frowned, but we were bartering now. Her favorite type of conversation.

“Not outside. You can use the scope inside. When I return, we’ll fly some of my route around the city, as practice.” She saw my frustration. “Promise me you’ll keep inside? No visiting? No sending whipperlings? We cannot lose another bird.”

“For how long?” A mistake. My question broke at the end with the kind of whine that hadn’t slipped out in years. My advantage dissipated like smoke.

Nat, on Ezarit’s other side, pretended he wasn’t listening. He knew me too well. That made it worse.

“They will go when they go.” She winced as sounds of Mondarath’s mourning wafted through the shutters. Peering out again, she searched for the rest of her escort. “Listen for the horns. If Mondarath sounds again, or if Viit goes, stay away from the balconies.”

She looked over her shoulder at me until I nodded, and Nat too.

She smiled at him, then turned and wrapped her arms around me. “That’s my girl.”

I would have closed my eyes and rested my head against the warmth of her chest if I’d thought there was time. Ezarit was like a small bird, always rushing. I took a breath, and she pulled away, back to the sky. Another guard joined the first on the balcony, wearing faded yellow wings.

I checked Ezarit’s wings once more. The fine seams. The sturdy battens. They’d worn in well: no fraying, despite the hours she’d flown in them. She’d traded five bolts of raw silk from Naza tower to the Viit wingmaker for these, and another three for mine. Expensive but worth it. The wingmaker was the best in the north. Even Singers said so.

Furled, her wings were a tea-colored brown, but a stylized kestrel hid within the folds. The wingmaker had used tea and vegetable dyes—whatever he could get—to make the rippling sepia pattern.

My own new wings leaned against the central wall by our sleeping area, still wrapped. Waiting for the skies to clear. My fingers itched to pull the straps over my shoulders and unfurl the whorls of yellow and green.

Ezarit cloaked herself in tea-colored quilted silks to protect against the chill winds. They tied over her shoulders, around her trim waist and at her thighs and ankles. She spat on her lenses, her dearest treasure, and rubbed them clean. Then she let them hang around her neck. Her tawny cheeks were flushed, her eyes bright, and she looked, now that she was determined to go, younger and lighter than yesterday. She was beautiful when she was ready to fly.

“It won’t be long,” she said. “Last migration through the northwest quadrant lasted one day.”

Our quadrant had been spared for my seventeen years. Many in the city would say our luck had held far too long while others suffered. Still, my father had left to make a trade during a migration and did not return. Ezarit took his trade routes as soon as I was old enough to leave with Elna.

“How can you be sure?” I asked.

Elna patted my shoulder, and I jumped. “All will be well, Kirit. Your mother helps the city.”

“And,” Ezarit said, “if I am successful, we will have more good fortune to celebrate.”

I saw the gleam in her eye. She thought of the towers in the west, the wealthier quadrants. Densira had scorned us as unlucky after my father disappeared, family and neighbors both. The aunts scorned her no longer, as they enjoyed the benefits of her success. Even last night, neighbors had badgered Ezarit to carry trade parcels for them to the west. She’d agreed, showing respect for family and tower. Now she smiled. “Perhaps we won’t be Ezarit and Kirit Densira for long.”

A third guard clattered to a landing on the balcony, and Ezarit signaled she was ready. The tower marks on the guards’ wings were from Naza. Out of the migration path; known for good hunters with sharp eyes. No wonder Nat stared at them as if he would trade places in a heartbeat.

As Ezarit’s words sank in, he frowned. “What’s wrong with Densira?”

“Nothing’s wrong with Densira,” Elna said, reaching around Ezarit to ruffle Nat’s hair. She turned her eyes to the balcony, squinting. “Especially since Ezarit has made this blessed tower two tiers higher.”

Nat sniffed, loudly. “This tier’s pretty nice, even if it reeks of brand-new.”

My face grew warm. The tier did smell of newly grown bone. The central core was still damp to the touch.

Still, I held my chin high and moved to my mother’s side.

Not that long ago, Nat and I had been inseparable. Practically wing-siblings. Elna was my second mother. My mother, Nat’s hero. We’d taken first flights together. Practiced rolls and glides. Sung together, memorizing the towers, all the Laws. Since our move, I’d seen him practicing with other flightmates. Dojha with her superb dives. Sidra, who had the perfect voice for Laws and already wore glorious, brand-new wings. Whose father, the tower councilman, had called my mother a liar more than once after we moved uptower, above their tier.

I swallowed hard. Nat, Elna, and I would be together in my still-new home until Ezarit returned. Like old times, almost.

In the air beyond the balcony, a fourth figure appeared. He glided a waiting circle. Wings shimmered dove gray. Bands of blue at the tips. A Singer.

A moment of the old childhood fear struck me, and I saw Nat pale as well. Singers sometimes took young tower children to the Spire. It was a great honor. But the children who went didn’t return until they were grown. And when they came back, it was as gray-robed strangers, scarred and tattooed and sworn to protect the city.

The guards seemed to relax. The green-winged guard nudged his nearest companion, “Heard tell no Singer’s ever been attacked by a skymouth.” The other guards murmured agreement. One cracked his knuckles. Our Magister for flight and Laws had said the same thing. No one ever said whether those who flew with Singers had the same luck, but the guards seemed to think so.

I hoped it was true.

Ezarit signaled to the guards, who assembled in the air near the Singer. She smiled at Elna and hugged her. “Glad you are here.”

“Be careful, Ezarit,” Elna whispered back. “Speed to your wings.”

Ezarit winked at Nat, then looked out at the sky. She nodded to the Singer. Ready. She gave me a fierce hug and a kiss. “Stay safe, Kirit.”

Then she pushed the shutters wide, unfurled her wings, and leapt from the balcony into the circle of guards waiting for her with bows drawn.

The Singer broke from their formation first, dipping low behind Wirra. I watched from the threshold between our quarters and the balcony until the rest were motes against the otherwise empty sky. Their flight turned west, and disappeared around Densira’s broad curve.

For the moment, even Mondarath was still.

Nat moved to pull the shutters closed, but I blocked the way. I wanted to keep watching the sky.

“Kirit, it’s Laws,” he said, yanking my sleeve. I jerked my arm from his fingers and stepped farther onto the balcony.

“You go inside,” I said to the sky. I heard the shutter slam behind me. I’d broken my promise and was going against Laws, but I felt certain that if I took my eyes off the sky, something would happen to Ezarit and her guards.

We’d seen signs of the skymouth migration two days ago. House birds had molted. Silk spiders hid their young. Densira prepared. Watchmen sent black-feathered kaviks to all the tiers. They cackled and shat on the balconies while families read the bone chips they carried.

Attempting to postpone her flight, Ezarit had sent a whipperling to her trading partners in the south and west. They’d replied quickly, “We are not in the migration path.” “We can sell our honey elsewhere.” There would be none left to mix with Mondarath’s herbs for the southeast’s medicines.

She made ready. Would not listen to arguments. Sent for Elna early, then helped me strip the balcony.

Mondarath, unlike its neighbors, paid little mind to preparations. The skymouth migration hadn’t passed our way for years, they’d said. They didn’t take their fruit in. They left their clotheslines and the red banners for Allmoons flapping.

Around me now, our garden was reduced to branches and leaves. Over the low bone outcrop that marked Aunt Bisset’s balcony, I saw a glimmer. A bored cousin with a scope, probably. The wind took my hair and tugged the loose tendrils. I leaned out to catch one more glimpse of Ezarit as she passed beyond the tower’s curve.

The noise from Mondarath had eased, and the balconies were empty on the towers all around us. I felt both entirely alone and as if the eyes of the city were on me.

I lifted my chin and smiled, letting everyone behind their shutters know I wasn’t afraid, when they were. I panned with our scope, searching the sky. A watchman. A guardian.

And I saw it. It tore at my aunt’s gnarled trees, then shook loose the ladder down to Nat’s. It came straight at me fast and sure: a red rip in the sky, sharp beak edges toothed with ridge upon ridge of glass teeth. Limbs flowed forward like thick tongues.

I dropped the scope.

The mouth opened wider, full of stench and blood.

I felt the rush of air and heard the beat of surging wings, and I screamed. It was a child’s scream, not a woman’s. I knew I would die in that moment, with tears staining my tunic and that scream soiling my mouth. I heard the bone horns of our tower’s watch sound the alarm: We were unlucky once more.

My scream expanded, tore at my throat, my teeth.

The skymouth stopped in its tracks. It hovered there, red and gaping. I saw the glittering teeth and, for a moment, its eyes, large and side-set to let its mouth open even wider. Its breath huffed thick and foul across my face, but it didn’t cross the last distance between us. My heart had stopped with fear, but the scream kept on. It spilled from me, softening. As the scream died, the skymouth seemed to move again.

So I hauled in a deep breath through my nose, like we were taught to sing for Allmoons, and I kept screaming.

The skymouth backed up. It closed its jaws. It disappeared into the sky, and soon I saw a distant ripple, headed away from the city.

I tried to laugh, but the sound stuck in my chest and strangled me. Then my eyes betrayed me. Darkness overtook the edges of my vision, and white, wavy lines cut across everything I saw. The hard slats of the shutters counted the bones of my spine as I slid down and came to rest on the balcony floor.

My breathing was too loud in my ears. It roared.

Clouds. I’d shouted down a skymouth and would still die blue-lipped outside my own home? I did not want to die.

Behind me, Nat battered at the shutters. He couldn’t open them, I realized groggily, because my body blocked the door.

Cold crept up on me. My fingers prickled, then numbed. I fought my eyelids, but they won, falling closed against the blur that my vision had become.

I thought for a moment I was flying with my mother, far beyond the city. Everything was so blue.

Hands slid under my back and legs. Someone lifted me. The shutters squealed open.

Dishes swept from our table hit the floor and rolled. Lips pressed warm against mine, catching my frozen breath. The rhythm of in and out came back. I heard my name.

When I opened my eyes, I saw the Singer’s gray robes first, then the silver lines of his tattoos. His green eyes. The dark hairs in his hawk nose. Behind him, Elna wept and whispered, “On your wings, Singer. Mercy on your wings.”

He straightened and turned from me. I heard his voice for the first time, stern and deep, telling Elna, “This is a Singer concern. You will not interfere.”

2

SENT DOWN

The Singer came and went from my side. He checked my breathing. His fingers tapped my wrist.

Elna and Nat swirled around the table like clouds. I heard Elna whisper angrily.

When I found I could hold my eyes open without growing dizzy, Nat had disappeared. The Singer sat at my mother’s worktable. His draped robes puddled on the floor and obscured her stool. As the sun passed below the clouds, he sat there fingering a skein tied with blank message chips.

In the dark, his knife scraped against one bone chip, then another.

The room felt tight-strung, an instrument waiting to be played.

With the sunrise, Densira neighbors began clattering onto our balcony. They brought a basket of fruit, a string of beads.

“The tower is talking,” Elna said. “About the miracle. That it’s a skyblessing.”

The Singer waved away our visitors. He positioned a tower guard on the balcony.

Occasionally, the guard peered through the shutters and shook his head, like kaviks did when they were molting. “Lawsbreaker,” he muttered. He told any who would listen how stupid I’d been.

I caught pieces of his words on the wind.

“It came right for her. The fledge stood out on the balcony with the lens of that scope glinting in the sun. Should have gobbled her up. Would have shot her myself, attracting a mouth to the tower like that.” He waved our neighbors away. “Don’t waste your goods on her. She’s not skyblessed. She’s bad luck. Should tie enough Laws on her that she’ll rattle when she moves.”

The people of Densira did not listen. Elna scrambled to find places for everything they brought.

She took the guard a cup of tea. “Luck was with her, Risen. The tower has luck now, because of Kirit. The skymouth fled.”

The Singer cleared his throat loudly. Elna jostled the cup. Nearly spilled the tea. The Singer looked as if he wanted to have Elna swept from the tower and silenced.

I tried to say something helpful, but my voice rasped in my throat.

“Don’t try to speak, Kirit.” Elna returned to my side. The Singer glared again, then rose, muttering about needing a new sack of rainwater. He must have decided to keep me alive a little longer.

She propped me up. Around me, the bone lanterns’ glow cast halos and small stars against the pale walls. The rugs and cushions of the place I’d shared with my mother since the tower rose were swathed in shadow.

Elna wrapped me in a quilt, tucking the down-filled silk beneath me. Instead of warming, I shook harder. The Singer returned and held my wrist between his thumb and forefinger. He reached into his robe. Took out a small bag that smelled rich and dark. Metal glittered in the light.

A moment later, he handed me a tiny cup filled with sharp-smelling liquid. It burned my throat as it went down, then warmed my chest and belly. It took me a moment to realize I wasn’t drinking rainwater from my usual bone cup. He’d given me a brass cup so old the etching was nearly worn away. It warmed in my hands as the glow crept up my arms. Calm followed warmth until I was able to focus on the room, the smell of chicory brewing, the sound of voices.

Elna disappeared when the Singer glared at her a third time. He gave me a stern look. Waited for me to speak. I wished Ezarit sat beside me.

“They think you are skyblessed,” he said when I did not speak on his cue.

I blinked at the words and closed my eyes again. Skyblessed. Like the people in the songs, who escaped the clouds, or those who survived Lith.

The Singer’s tone made it clear that he thought me nothing of the sort.

“Your example will tempt people to risk themselves. We have Laws for a reason, Kirit. To keep the city safe.”

I found that hard to argue. I sat up straighter. My head pounded. I looked around the empty tier, at the lashed shutters, anywhere but at the Singer standing before me, his hands folded into his robe.

“You are old enough to understand duty to your tower. You know our history. Why we can never go back to disorder.”

I nodded. This was why we sang. To remember.

“Yet you are still part of a household. Your mother is still responsible for you. Even while she’s on a trading run.”

He was right. She wouldn’t learn what I’d done until she flew close enough to the north quadrant for the gossip to catch up with her. I imagined her sipping tea at a stopover tower. Varu, perhaps. And hearing. What her face would look like as she tallied the damage to her reputation. To mine. Bile rose in my throat, despite the calming effect of whatever was in that cup.

The Singer leaned close. “You know what you did.”

I’d broken Laws. I knew that. I’d attracted a skymouth with my actions. A punishable offense. Worse, I drew a Singer’s attention, which could affect Densira. Councilman Vant, Sidra’s father, would sanction me, and my mother too, for my deeds.

But that fell below the Singers’ jurisdiction. They only dealt with the big Laws. I sipped at the cup to conceal my confusion. Cut my losses. “I broke tower Laws.”

He lowered his voice. “Not only that, you lived to tell about it. How did you do that, Kirit Densira?” His eyes bored into mine, his breath rich with spices. He looked like a hawk, looming over me.

Elna was nowhere to be seen. I looked at my fingers, the soft pattern on the sleeve of my robe that Ezarit brought back from her last trip. Stall, my brain said. Someone would come.

I met the Singer’s gaze. Hard as stone, those eyes.

“I am waiting.” He spoke each word slowly, as if I wouldn’t understand otherwise.

“I don’t know.”

“Don’t know what?”

“Why I am still alive.”

“You’ve never been in skymouth migration before?”

I shook my head. Never. Wasn’t that hard to believe. Everyone knew the northwest quadrant had been lucky.

“What about the Spire? Never to a market there, nor for Allsuns?”

Shaking my head repeatedly made the room spin. A low throb gripped the base of my skull. My voice rasped. “She said we’d go when we were both traders.”

He frowned. Perhaps he thought I lied. “Don’t all citizens love to visit the Spire’s hanging markets at Allsuns, pick over the fine bone carvings, and watch the quadrant wingfights?

I shook my head. Not once. Ezarit never wanted to go, nor Elna. They avoided the Singers more than most. How could I convince him I told the truth?

“Do you know what you’ve done?”

I shook my head a third time, while pressure pounded my temples. I did not know, and I felt nauseated. I could see no way for me to get away from this Singer. Even seated, he loomed over me, tall and thin and sour-faced. Despite this, his hands were smooth, no deep lines marked his face beneath the tattoos; he might not have been much older than me.

“I don’t know what you want me to say. I went on the balcony. A skymouth came. I screamed, and it—”

I stopped speaking. I’d screamed. The skymouth had halted. Why? People who were close enough to a skymouth to scream died.

The Singer’s gaze bored into mine. His frown deepened. He turned away from me and looked at the balcony. Then back to me.

“There are those who can hear the city all the time. Not only when it roars. They learn to speak its language. You know that, right?”

I bowed my head. “They become Singers. They make sure we continue to rise, instead of falling like Lith.” Our Magister, Florian, had taught us this long ago. If tower children became Singers, their families were rewarded with higher tiers; their towers with bridges. But the Singers themselves were family no longer. Tower no longer. They severed themselves from city life; enforced Laws even on those they once loved. Nat’s father, for instance. Though I’d been too young to see it, I’d heard stories. I imagined now a Laws-weighted figure thrown to the clouds. Arms and legs churning in place of missing wings. Failing. Falling. Tears pricked my eyes.

This Singer took my arm and squeezed hard. I locked my teeth together to avoid crying out. His fingers pressed into my skin, dimpling pale rings around the pressure points. “Kirit Densira, daughter of Ezarit Densira, I place you under Spire fiat. If you reveal anything that I say now to anyone, you will be thrown down. If you fail to tell the truth, you will be thrown down. Do you understand?”

My head throbbed worse than ever, and I leaned hard against his grip. “Yes.” Anything to get free of this man.

“Some among the Singers can speak to monsters.”

“What do you mean?”

“There are five people in the city who can stop a skymouth with a shout. All Singers. Except one.”

He stared at me. He meant me. I was the fifth.

“Kirit.” He paused. “You are not skyblessed.”

I bowed my head. I hadn’t thought so.

He released a breath. Scent of garlic. “But you could be something more. Someone who helps to keep the city safe in its direst need.”

As my mother did. I raised my eyebrows. “How?”

“You must come into the Spire with me.”

The way he said it, I knew he didn’t mean for a visit. I jerked backwards. Neck and shoulder muscles tensed into a rejection of him. And yet he held me. Tried to shake me out of it. No.

I would not leave the towers. I would not go into the Spire. Not for anything.

Traders flew the quadrants freely, making elegant deals. They connected the city, helped weave it together. Better still, traders were not always tied to a single tower and its fate; they saw the whole city, especially if they were very good, like Ezarit. That was what I wanted. What I would choose when I was able.

I stalled. “I have already put my name in for the next wingtest.”

His turn to shake his head. “That hardly matters. Come with me. Your mother will be well honored for your sacrifice. Your tower too.”

Sacrifice? No. Not me. I would ply the winds and negotiate deals that let the towers help one another. I would be brave and smart and weave beads in my hair. I would not get locked in an obelisk of bone and secrets. I wouldn’t make small children cry, nor etch my face with silver tattoos.

I yanked my arm away. Scrambled off the table, my knees wobbly, toes tingling. Two steps, and I hit the floor. I tried to crawl to the balcony, to get to Aunt Bisset’s, to get back to Elna.

The Singer grabbed me up by the neck of my robe. His words were soft, his grip fierce. “You have broken the Laws of your tower. Endangered everyone here. Some think you’re skyblessed, but that will wear off. Others think you are a danger, unlucky.”

“I am no danger!”

“I will encourage these thoughts. What then? Soon the tower will grow past you. Your bad luck will sour your trades and your family’s status. You will be left behind. Or worse. You will be Densira’s pariah for every bad thing.”

I saw my future as he drew it. The tower turned against me, against my mother. Ezarit, living within a cage of shame.

“As a Singer, you will be respected and feared. Your mother and Elna and Nat will be forgiven your Lawsbreaks.”

The household. He would punish Elna and Nat too. And Ezarit. For my decisions. I needed to bargain with this man. How did I do that? How would Ezarit have done it? I groped for memories of her trading stories, for how she would have turned him away. She would have tried to trade, to haggle. If she’d nothing to trade, she’d bluff.

“I am too old to take.” I’d never heard of someone nearly at wingtest being taken by the Singers.

“You are still a dependent in the eyes of your tower.”

“In that case,” I said, resisting the urge to argue his point, “my mother would never permit this.” I was certain of that.

“Your mother is not here. Won’t be back until nearly Allmoons.”

“You can’t take me without her permission,” I said. “It says so in Laws.” And once I have my wingmark, Singer, I will be an apprentice. Able to decide my own path. Singers do not take apprentices from the city, except for egregious Lawsbreaks. I coughed to conceal my shudder at that possibility. Then I straightened. “Ezarit would bring down a storm on the Spire so great, you’d be begging the clouds to pull you back up.” I yanked my arm from his grip.

The Singer smiled, all but his eyes. My skin crawled. “Singers are more powerful than traders, Kirit. Even Ezarit. No matter what your mother thinks.”

I drew a deep breath. “I will not go with you.”

The Singer straightened. “Very well. You would be unteachable at this age if you did not desire to become a Singer anyway.”

I’d changed his mind. I couldn’t believe it. It felt too easy.

“You will stay in Densira until the wingtest. Then we will talk again.” He rose and reached back to release his wings. He was leaving. Then he paused. Frowned. The tattoos on his cheeks and chin creased and buckled.

“Of course,” he said, “you did break tower law.” He drew a cord from his sleeve, tied with four bone chips. “The tower councilman has sent you, Elna, Nat, and your mother a message. Vant is of the opinion, which I have reinforced, that you are in no way skyblessed, no way lucky. That the guard must have driven away the skymouth with noise and arrows. That you must be censured severely to avoid future danger to the tower.”

I took the chips. Freshly carved. Approved by Councilman Vant. Two were thin, light: Nat’s and mine. We were assigned hard labor, cleaning four tiers downtower.

I gasped. That could take well past the wingtest to finish.

Heavier still were Elna’s and Ezarit’s chips. They felt thick. Not the thickest, I knew, but still true Laws chips. Permanent, unless Ezarit could bargain with Vant so that he let her untie them.

As promised, they were punished for my deeds. For both the Lawsbreak and for refusing the Singer. Nat and I could miss the wingtest. We would certainly miss the last flight classes, when the Magister did his most intensive review. I could lose my chance at becoming an apprentice this year. Perhaps forever.

My head ached, and I tried hard to swallow. I knew I could have been thrown down for endangering the tower. But censure was bad too. Everything was wrong now.

And not just for me. I held Elna’s, Nat’s, and my mother’s fates in my hand.

The Singer raised his eyebrows. Would I change my mind? Would I give in and go with him?

I stared back at him. Swallowed. Shook my head. Densira seemed to fall silent as we stared each other down.

“My name is Wik. Remember it,” he said. “I will find you at Allmoons, Kirit Densira. By then, you will want to come with me.”

Trapped behind walls. Gray wings and robes, silver tattoos. Lawsbreakers thrown down, arms flailing. No family. No tower but the Spire.

I would find a way to avoid that. I had to.

The sound of Elna and Nat returning startled the Singer. He swept from our quarters, unfurling his wings as he crossed to the balcony. Nat dodged left to avoid being struck.

I walked unsteadily to greet them, waving my hand to dissuade Elna from bowing in custom.

Shading my eyes against the sunset, I watched the Singer’s silhouette shrink as the breeze carried him away. He soared towards the city’s center, towards the Spire.

My shoulders dropped. I sank down to rest on my mother’s stool. Nat came to stand by me. “I’m sorry,” he murmured. “For locking you out.”

I looked up at him. Wished I had words. But anything I said could reveal me, break the Singer’s fiat, and endanger Nat and Elna even more. They had enough trouble coming because of me.

I held out the markers, with their sentences on them.

Elna read hers and sucked in her breath. Then she read Nat’s and mine, saw they were blessedly temporary. Her eyes watered. “Serves you right,” she said. But she heaved the words at us with such relief, I knew she’d been afraid.

I did not want to think of Naton, Nat’s father, now. But I was sure Elna thought of the bone markers she’d held the day Naton was thrown down. A skein of Treason Laws, making him first chosen for Conclave, the ritual to appease the city.

Those chips were the heaviest the Singers dispensed.

Ours were much lighter. Tower Laws. Warnings. We would not have to wear them forever.

After he read his chip, Nat’s face was a puzzle. “Why do I get punished for what Kirit did?”

Because I would not sacrifice myself for you, Nat. Because I would not go with the Singer, you are punished. I opened my mouth to tell him. To say I was sorry.

But Elna turned on him. “Oh, you’re not innocent. You stood by and watched.” Her look stopped him cold. He glanced at me from under his lids instead. She huffed and began piling foods from the offerings into a basket. “Might as well get packed up, then. The council will be up.”

“Packed?” I couldn’t fathom why.

“They’ll want you two as low as they can send you,” Elna said. “Closer to your duties, but also much more shameful, isn’t it? So they’ll move you down, to my tier.”

I walked towards the back of our quarters to retrieve my sleeping mat and to get away from Nat’s glare. My new wings leaned against the inner wall, dark beside the slick bone column. Vant had nicked “no flight” on our punishment chips. Fine.

I would find a way to finish the cleaning in time. I would fly the wingtest. I promised myself this as I fed the silk spiders and the whipperling. Watered the kavik. They’d survive on their own until Ezarit returned. I hoped she would be quick.

My hands went through the motions while my mind whirred. I saw the skymouth’s teeth flash once again. Felt the heat of its breath.

Nat shook me by the shoulders. “Stop it!”

“What?”

“You were keening. It sounded horrible. Hurt my ears. Worse than your singing.”

I touched my face. My cheeks were wet. How had that happened? I hadn’t cried in front of someone since my first flight group, when I was very young.

Back then, the meanest among them, Sidra, had pretended Nat didn’t exist at all. “He’s nothing. His father broke Laws. Singers said so.” But she’d rounded on me. Teased me for my tuneless renderings of the first Laws we learned. “Your father must have fed himself to a skymouth to keep from being there to hear you cry.” The flight group, young as chicks, collapsed into laughter until the Magisters came with their nets to take us into the sky for our first flight. Then everyone’s voice froze tight in fear.

We’d only flown for a few minutes that day, tumbling into the tightly woven nets as we learned the winds around Densira. I’d rushed home and, in answer to Ezarit’s “how was it?” my nose and eyes had run like rainspouts.

“Sidra’s father talks too much, up at the top of Densira,” she’d said bitterly. “Your father didn’t return from a trade run. He could have been taken by a skymouth, but no one knows for certain. It wasn’t your doing.” And that was all she ever said.

She’d walked away from me, shoulders hunched, while I buried my face in my sleeping mat. She’d left early the next morning for the Spire, stopping to kiss my head. “Don’t let them tell you who you are, Kirit. Don’t let them see you cry.” I’d pretended to be asleep. But I heard her.

She’d petitioned the Singers that day, though she would not say for what. But her trade routes got better, and, when the tower grew, we were allowed to move to the new tier. Above Vant and his family. A great honor.

Now she was on a trade, and I’d wept again. For whom? For what? Nat still shook me, gently. “I’m all right,” I sniffled. He let go.

“What did the Singer say?” he asked.

My mouth went dry. I shook my head.

“Fine, Kirit.”

“It’s not that, Nat. I can’t say what he said.”

He opened his mouth to press me for more, but a clatter at the balcony signaled Councilman Vant’s arrival, along with the tower guard from this morning. They held a net basket between them.

“I’m not getting in that thing,” Nat said.

“No.” The councilman shook his head. His jowls jiggled. “You’re not. Kirit is.”

My jaw dropped. To be sent downtower was one thing. To be sent by basket like an invalid or a cloudbound offering was entirely another. I began to protest, but the councilman held up a finger. “Singer’s orders.” He smiled with pleasure.

The councilman’s enjoyment of my mistake made my stomach clench. Perhaps he hoped this was the first of many small falls.

My mother was not here to ease the way with kind words or gifts. I must do what he said, without making things worse.

I looked around once more before climbing in the basket. Our wide quarters were so recently grown atop the tower that the inner walls hadn’t yet begun to thicken. The space was comfortable, for all its newness. We had cushions from Amrath tower, and woven storage baskets in elegant patterns from Bissel. Chimes made from reclaimed metal so old they’d worn smooth of their past hung from the ceiling in the center of the room.

I realized too late that I didn’t want to leave this height for downtower’s stink and worry. Councilman Vant’s family had likely felt the same, as the tower grew past them. They’d been accustomed to being at the top. But towers rose according to need. Densira hadn’t risen for years, until Singers arrived with their rough scourweed and chants. Until they’d coaxed the bone tower into growing a new level. But Densira kept groaning. Once, while I’d lived downtower, Nat and I had skipped flight to cruise over the expanse of new-grown bone, and I had spotted the beginnings of a second tier, a natural one, emerging atop the one the Singers had called in the traditional way. After two seasons where the walls creaked and the wind cut ghost patterns around the emerging core, the tier thickened and steadied enough to be occupied.

My find was a tiding, my mother said to anyone who’d listen. She conferred with the Singers and they named our family the occupants, though we waited another season to move. No one had wanted to interfere with the tower’s rise. Then we’d climbed, all of us, past Vant’s tier, while quite a few other families filled in our former quarters below. Nat had been right to tease yesterday that we were only newly risen, our tier as well. It still stung.

Even now, as I prepared to leave, the central wall creaked and settled. It whispered tower dreams to us and to its cousins all across the city. I wished that the city would speak at this moment. Then the Singers would focus on its message, and not on me.

Elna and Nat descended the rope ladder and left me in my home. Two days ago, I would have given anything to leave it. Now I wished I could stay.

The guard cleared his throat. I heaved my things into the basket, and the councilman helped me in.

“Kirit Lawsbreaker, you’re a poor example to your tower. Let your penance make you humble. Let it be of service to Densira,” he said. I waited for him to say more. Instead, he and the councilman swung me over the edge of the balcony, making the basket spin. I twisted in the air, wingless, like an infant, as I sank below the floor where my family lived.

Above, the guard played the rope across the cleats cut into our balcony. As the basket jerked down and down again, people emerged on Mondarath’s and Densira’s gardens to watch. My skin prickled with the attention, but there was nothing I could do. The fiber net held me tight against the wind, which pushed it dizzyingly against the edge of the balcony. The ropes groaned as they bore my weight.

My eyes raked the sky for another mouth or more teeth, found none.

The basket stopped and then started moving again precipitately. Perhaps the guard and councilman had argued about whether to let the rope go, whether to drop me over the edge. They’d be free of the luck, good or bad, that now plagued their peaceful and well-ordered tower. As sometimes happened with invalids.

The net creaked. I laced my fingers around two of the larger knots and held tight.

Below, the tower disappeared with its neighbors into the depths, growing indistinct long before the cloudtop obscured everything. Farther down, the songs said, the tiers grew together, even some of the towers, as the bone cores expanded out, filling the hollows of old quarters. Even farther down, well below the clouds, lay legend. The oldest songs sang of a bone forest, and the people who climbed it and lived because they kept going higher. And so we still climbed.

Except me. I sank lower, at least for now.

After a lifetime of swinging in my cage, edging lower, then swinging again, I reached Elna’s tier. She hooked the net basket with a bone crook, the one she used for bringing in market baskets. Perhaps this very basket. It reeked of onions. Elna and Nat pulled on the crook together and drew the basket onto her small balcony. I climbed out and sat on the ground for a moment, catching my breath.

Elna tugged on the rope twice, and the councilman and his guard yanked up the empty basket.

Far below, the clouds glowed pink with sunset. With Allmoons so near, we were flush with the kind of light that faded quickly. The kind that sank to cinder only a few hours after it kindled. Elna’s quarters were ruddy with the declining sun.

I looked around my prison. The same walls and tapestries of my earliest memories, but smaller as the inner wall thickened. One day, the tier would be filled with bone, and no one would live here. For now, Elna hummed Remembrance—sung at Allmoons and Allsuns—in the kitchen. And Nat. He looked at me now as if I’d made the skymouth with my bare hands on purpose. “You’re bad luck,” he grumbled. But I saw worry behind the anger. He needed to pass his wingtest too.

I wanted to snap back at him, but fighting with him would make things worse. I pressed my lips together.

Elna emerged from the kitchen to shake her head at both of us.

“Serves you both right.” She handed me a piece of lentil flatbread.

“I don’t see why I’m punished,” Nat said. “I’ll miss training. I’m not the numbhead who went out.”

She swatted him. “You didn’t stop her. And you closed the shutters. What do you think?”

He looked down. I saw myself through his eyes for a moment. Not Kirit the sometimes-sister, wing-friend of his childhood; now just the spoiled high-tower person who took his mother’s attention and got him censured.

“I wish I could change it all,” I said. I wanted him to remember what we’d been. Who I was before I moved uptower. To know that I was still the same person, still his friend. His almost-sister.

I tried hard not to care where I was, or about the wingtest and whether we’d miss it. Tried hard not to think of my mother, who’d left me behind. Elna was angry, sure. But with Elna, that didn’t matter. She held me close and I breathed in the scent of her skin, the onions she’d cooked. I relaxed, until she murmured, “Our Kirit, skyblessed.”

I groaned. So did Nat.

“You two.”

“You heard the Singer. I’m not skyblessed.”

Elna dipped her head in agreement. But over dinner and until she went to bed, I caught her looking at me with the same blend of reverence and horror that she’d given to the Singer.

Later, I wished she would wrap me up and tell me things would get better, as she had when I’d come in from flight with a bug in my eye or a scrape from the rough sinew nets.

I touched the Laws chip Councilman Vant tied to my wrist. One side was marked “Broke Fortify, endangered tower.” The other held my sentence, “Lowtower labor.” Nat’s bore the more general “Lawsbreaker.” We would wear them until the councilman cut them off.

Shivering, I pulled my quilt tight around me and curled up on my mat. It smelled of Ezarit’s spices and tea.

I was censured. I hoped for forgiveness. For a miracle.

Copyright © 2016 by Fran Wilde

Order Your Copy

A winged society faces the threat of ultimate extinction in the thrilling finale to Fran Wilde’s Bone Universe fantasy series, Horizon.

A winged society faces the threat of ultimate extinction in the thrilling finale to Fran Wilde’s Bone Universe fantasy series, Horizon.