There are some people out there who finish their Christmas shopping before Thanksgiving. We admire them–and we’re a little jealous of them, because we tend to leave things to the last minute. Luckily, we know the perfect last minute gift for nearly everyone: books. If you’re like us, and looking for some last minute gifts, never fear–we’re here to help. Here are some recommendations for the sci-fi fans in your life. Don’t forget to check out our Fantasy and Young Adult lists as well!

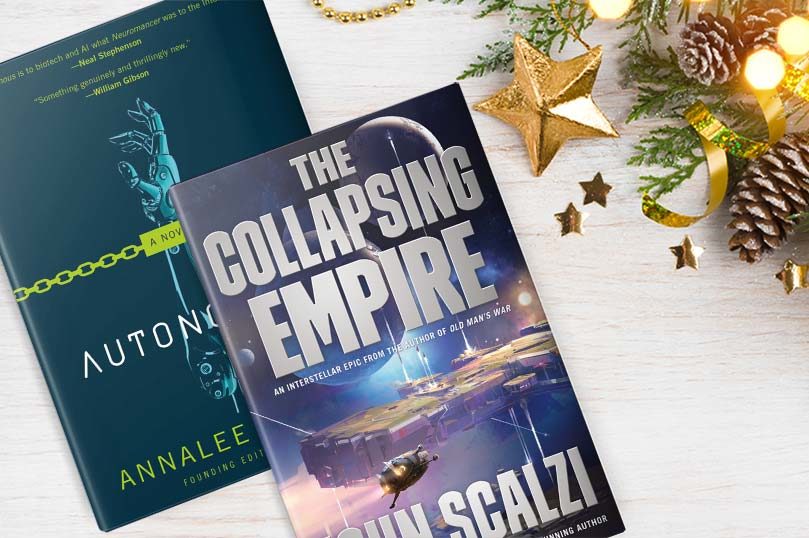

The Collapsing Empire by John Scalzi

Is there anyone on your list who loves the SyFy show The Expanse? If so, maybe give them a copy of The Collapsing Empire! What happens when the Flow, the extradimensional interstellar highway in the universe, collapses? Can thousands of stranded planets, thousands of light years apart, be saved?

Is there anyone on your list who loves the SyFy show The Expanse? If so, maybe give them a copy of The Collapsing Empire! What happens when the Flow, the extradimensional interstellar highway in the universe, collapses? Can thousands of stranded planets, thousands of light years apart, be saved?

Walkaway by Cory Doctorow

The world can be a frustrating place these days. If there’s anyone on your list who’s contemplating just walking away from it all, then this is the book for them. In Walkaway, Hubert joins a small but growing segment of society who have decided to go fully off the grid, walking away from the breakdown of modern society. Then the walkaways discover something even the ultra-rich haven’t been able to buy: how to beat death. Now it’s war–a war that will turn the world upside down.

The world can be a frustrating place these days. If there’s anyone on your list who’s contemplating just walking away from it all, then this is the book for them. In Walkaway, Hubert joins a small but growing segment of society who have decided to go fully off the grid, walking away from the breakdown of modern society. Then the walkaways discover something even the ultra-rich haven’t been able to buy: how to beat death. Now it’s war–a war that will turn the world upside down.

Autonomous by Annalee Newitz

For the philosopher on your list, we recommend Autonomous. It’s a cerebral and morally complex read that covers issues from patent law, artificial intelligence, modern slavery, and more. Patent-pirate Jack, indentured military robot Paladin, and a diverse cast of characters will make you question whether freedom is truly possible in this frighteningly realistic future.

For the philosopher on your list, we recommend Autonomous. It’s a cerebral and morally complex read that covers issues from patent law, artificial intelligence, modern slavery, and more. Patent-pirate Jack, indentured military robot Paladin, and a diverse cast of characters will make you question whether freedom is truly possible in this frighteningly realistic future.

All Systems Red by Martha Wells

Everyone knows someone who just wants to be left alone binging Netflix. All Systems Red is the perfect companion read for them. All Murderbot wants is to be left alone to watch their shows, but of course, that’s not possible. Instead, they’re trying to protect near-suicidally curious scientists as they take on the powerful corporation that owns Murderbot.

Everyone knows someone who just wants to be left alone binging Netflix. All Systems Red is the perfect companion read for them. All Murderbot wants is to be left alone to watch their shows, but of course, that’s not possible. Instead, they’re trying to protect near-suicidally curious scientists as they take on the powerful corporation that owns Murderbot.

Luna: New Moon by Ian McDonald

Is there a Game of Thrones fan in your life who’s interested in branching out to science fiction? Then give them Luna: New Moon! In McDonald’s imagined future, the Moon is controlled by five ultra-rich corporations in a futuristic feudal society. Full of the power struggles, violence, and backstabbing that make Game of Thrones so fun, Luna: New Moon will suck you in and leave you wondering who you really should be rooting for in its vicious political atmosphere.

Is there a Game of Thrones fan in your life who’s interested in branching out to science fiction? Then give them Luna: New Moon! In McDonald’s imagined future, the Moon is controlled by five ultra-rich corporations in a futuristic feudal society. Full of the power struggles, violence, and backstabbing that make Game of Thrones so fun, Luna: New Moon will suck you in and leave you wondering who you really should be rooting for in its vicious political atmosphere.

Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card

For the person on your list who loves the classic literature, but maybe hasn’t dipped their toes into the world of genre yet, we recommend this science fiction must-read. Plus, this gorgeous new edition will fit right in between Albert Camus and Lewis Carroll on your shelves. Love the look of the new mini-edition? There are five more of them! (link to minis website)

For the person on your list who loves the classic literature, but maybe hasn’t dipped their toes into the world of genre yet, we recommend this science fiction must-read. Plus, this gorgeous new edition will fit right in between Albert Camus and Lewis Carroll on your shelves. Love the look of the new mini-edition? There are five more of them! (link to minis website)

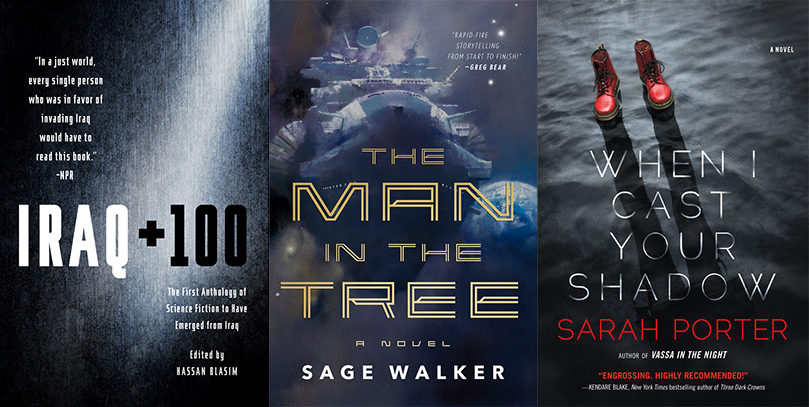

Iraq + 100 edited by Hassan Blasim

Perfect for the person who’s always the most interesting to talk to at parties, this groundbreaking anthology of science fiction from Iraq will give them fuel for 100 more interesting conversations. Iraqi authors use science fiction, allegory, magical realism and more to try to answer the question: what might your home country look like in the year 2103?

Perfect for the person who’s always the most interesting to talk to at parties, this groundbreaking anthology of science fiction from Iraq will give them fuel for 100 more interesting conversations. Iraqi authors use science fiction, allegory, magical realism and more to try to answer the question: what might your home country look like in the year 2103?

Steal the Stars by Mac Rogers and Nat Cassidy

Is there someone in your life who’s always recommending new podcasts for you to listen to? Then we have a double recommendation for them: Steal the Stars, in both book and podcast form! From the brand new imprint Tor Labs, Steal the Stars the podcast is the story of Dak and Matt as they go from guarding the biggest secret in the world, the alien Moss, to trying to steal it and fund their new lives together. The 14 episode series, by award-winning audio dramatist and playwright Mac Rogers, moves at a breakneck pace. Want to go deeper into the story? Then check out Nat Cassidy’s novelization!

Is there someone in your life who’s always recommending new podcasts for you to listen to? Then we have a double recommendation for them: Steal the Stars, in both book and podcast form! From the brand new imprint Tor Labs, Steal the Stars the podcast is the story of Dak and Matt as they go from guarding the biggest secret in the world, the alien Moss, to trying to steal it and fund their new lives together. The 14 episode series, by award-winning audio dramatist and playwright Mac Rogers, moves at a breakneck pace. Want to go deeper into the story? Then check out Nat Cassidy’s novelization!