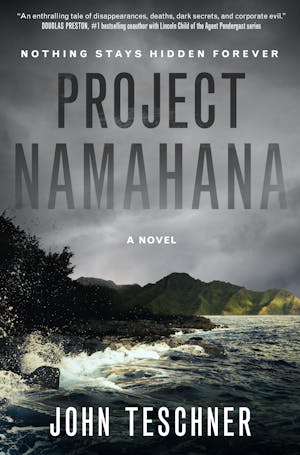

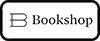

Nothing stays hidden forever…

Nothing stays hidden forever…

Two men, unified by a string of disappearances and deaths, search for answers—and salvation—in the jungles of Kaua‘i. Together, they must navigate the overlapping and complicated lines between a close-knit community and the hated, but economically-necessary corporate farms—and the decades old secrets that bind them.

Project Namahana takes you from Midwestern, glass-walled, corporate offices over the Pacific and across the island of Kaua‘i; from seemingly idyllic beaches and mountainous inland jungles to the face of Mount Namahana; all the while, exploring the question of how corporate executives could be responsible for evil things without, presumably, being evil themselves.

Project Namahana will be available on June 28th, 2022. Please enjoy the following excerpt!

CHAPTER ONE

Micah Bernt observed the beach park from the edge of the forest: a gravel road, a potholed parking lot, five ragged tents under sun-worn tarps. From this height, the ocean looked completely still and very far away, a flat blue desert one shade darker than the cloudless sky.

He heard a truck and slipped the pack from his shoulders into the tall grass. The driver never glanced his way, but he felt the eyes of the teenager sprawled in a beach chair in the bed. Bernt’s father was a Missouri Rhinelander, his mother Filipino. In California, people assumed he was Mexican. Here he could pass for local, as long as he didn’t open his mouth.

Bernt nodded and the boy nodded back.

He waited for the teens to carry their spearfishing gear under the ironwood trees. Then he shouldered his pack and followed the edge of the field until he found a narrow path leading into the forest. The tracks of dirt-bike tires interlaced in the hard-packed dirt. When the trail crossed a stream, he turned and followed the thin flow of water between mud-caked boulders. In a few minutes, he reached a spot where it pooled deep enough to dip a bottle without stirring any silt.

He scrambled out of the stream, dropped his pack and sank into the ferns, drank a liter of water in two gulps. No birds called in the forest. The stream was silent.

From his rucksack, he pulled an eight-by-eight tarp, twelve carabiners, and three rolls of 550 cord. He staked out a simple A-frame, hanging the tarp over a line between two trees. He took the second length of 550, tied one end to a grommet in the tarp and stretched it to a tree ten feet away. He wrapped the line from tree to tree until he had a rough perimeter at shin level. He strung a second line a couple feet outside the first, then clipped the two lines together with ten of the carabiners at equal distances. He hung the last two carabiners from the line in his tent.

Finally, he unstrapped his sleep system and laid his patrol bag under the tarp. He forced his heavy bag into a stuff sack for a pillow and laid it below the carabiners, where he would hear them jingle if anyone tripped the cord.

It was easier to go through the routines than resist them.

He left camp before dawn each morning. There were always people up early at the beach park: GT fishermen with their elaborate gear, uncles stopping by to throw net for an hour before work, kids in the tents getting ready for school. Bernt would walk up the road to wherever he’d left his car—a different place each night—then drive south to Kealia and park at the restrooms.

On windless mornings, glassy sets rolled in at Kealia like ripples on a pond. One or two at a time, surfers would tilt onto a peaking wave, coast down the face with a few laconic strokes, stand high near the collapsing water. Bernt came to recognize a few who caught more than the others. One, a woman, was the best. Seeing her flash along a fast right then carve her board three hundred degrees to extend the ride a few more seconds before gracefully topping the wave and reappearing with her feet high in the air, her arched back accentuating the slim cut of her bikini against her brown skin, was the high point of Bernt’s day.

He used shampoo and soap under the outdoor shower, wrapped a towel around his waist to strip off his wet shorts and dress himself, propped a mirror on the hood to shave, ran a dollop of product through his hair. He had no illusions that the runners and dog walkers on the trail, the surfers pausing to read the water before dashing down the beach, the handful of tourists up this early, didn’t grasp his situation with one glance.

If it was depressing to know the best part of his day was already over, he tried to take comfort in knowing this, the worst part, was almost over, too.

On his eighth day in the woods, Bernt interviewed for a job selling mowers and marine engines. The manager who interviewed him was barely out of high school. His grandfather had founded the shop. His great-grandfather had been an indentured laborer. Lining the walls above the kid’s desk were faded photos of families in crisp kimonos posing stiffly in front of plantation houses. Bernt asked the kid to drop the hourly by a buck fifty and increase his commission five percent, and he agreed. He’d catch hell from his grandfather when the old man found out.

That evening, Bernt drank a six-pack of Heinekens on a picnic table at Kealia. The waves were breaking cleanly, but he never saw the woman.

It was nearly dark as he walked toward the beach park. The parking lot was empty except for three ice heads lingering around a rusting pickup. He’d seen them before and given them little thought, beyond the operational concerns of the attention they might draw. He had a professional opinion on how they handled businesses—selling so blatantly and so close to the families in the tents—but this wasn’t his community. Anahola was a Home Lands area. He assumed their disrespect was noted. Someone would take care of it eventually.

He was moving through the shadowed tree line when a rusty van pulled into the lot, a wooden rack screwed straight into its roof, a pile of battered surfboards and random junk roped haphazardly on top, one rear window jammed askew. A bearded man unfolded from the driver’s seat, his head darting until his gaze froze on the baggie that flashed in an ice head’s palm. A woman watched keenly from the passenger seat, surveying them all with a vigilance bordering on hatred.

Haoles.

Just a short time on island and the word came automatically. Whether they lived out of a van or owned ocean-front property, they all reminded him of the outnumbered white kids at his high school: pitifully eager to fit in or resolutely oblivious to anyone outside their tiny circle.

He was about to turn his back and step into the forest when he saw the woman frown and twist in her seat, speak angrily to someone. A spark flared in his brain. In ordinary situations, threat assessment was automatic and unconscious. But an error—even as minor as the occupancy of a vehicle—set off alarms. He looked more closely. Then he stepped out of the tree line.

He reached the group as the bearded man was passing over the folded bills. Bernt caught his hand and threw the man’s fist back at him, easily causing him to stagger back toward the van. “If I see you here again,” Bernt whispered, “I’ll keep the money. And I’ll cut you.”

Anger boiled somewhere behind the man’s eyes. But only fear was strong enough to cut through his confusion. The woman was more collected.

“Fuck you!” she screamed. “You need to mind your own fucking business. Who the fuck you think you are? You better get your ass up, Omen, and—”

Bernt opened the door and shoved Omen into the driver’s seat. The man gave his woman a terrified glance and tried to bolt back into Bernt’s arms, but Bernt slammed the door on him.

“Get the fuck out of here!” he screamed, banging the van. It rolled forward, and for a moment Bernt locked eyes with the little boy standing between the two rear seats.

“I never knew they had one buk buk superhero. You get one magic bolo knife or what?”

Bernt turned. One of the ice heads was just a few feet away. His cheeks were hollow and his lips scabbed over, but he was still good-looking, vaguely European, with a deep tan and curly black hair. He wore work boots and jean shorts sagging from his skinny hips. His forearms were ropy with muscle. He had the hands of a carpenter. His hair was cropped close. A few Army tattoos, a few prison. Three inches on Bernt, at least.

“I not going give you no humbug for harassing my customers. I never like that haole bitch. But you need finish what they started.” He flashed the baggie in his palm.

“No thanks,” said Bernt.

The man turned to his friends. He was clearly the leader of their little gang. “No thank you. This Flip talk like one haole, an’ fresh off the plane, too.”

Bernt turned to walk away, but the man stepped with him.

“Where you from?”

“Kapaa,” Bernt lied.

“You stay Kapaa but you sleep in the forest? You must get trouble with your wahine.”

Bernt said nothing.

“Yeah we seen you.” For an instant, Ice Man’s eyes turned keen and piercing. “And we know you never like no pilikia. Just pay up. One hundred only.”

He walked as he spoke, drifting right, making it harder with each step for Bernt to keep all three in front of him.

“Nah.”

Ice Man grinned, his teeth black stubs. “So what then, you like spar?”

All three were moving now, fanning out. The other two didn’t look like fighters, but they didn’t need to be.

Ice Man raised his hands.

In one motion, Bernt slipped the pack from his shoulder and lifted the heavy steel ASP from its sleeve. He let his wrist drop with the weight, flicking just enough for the baton to telescope and lock with a satisfying click.

The stranger grinned. There were plenty of nights Bernt would have been happy to see him pull a blade. But he was glad when Ice Man gestured for his boys to stand down.

After he’d watched the headlights bump across the bushes and sweep down the road, Bernt returned to his camp. He could bug out with his essentials in under two minutes, but he took the time to remove all trace. Then he walked deeper into the forest, through clearings cluttered with burnt-out cars, until he reached the ocean. He chose a small cove to wait out the night and settled into the moonshadow cast by a tall boulder.

It was always lonely, to be awake and alert in the darkness. But he was never alone.

At Benning there’d been a Weapons Sergeant who’d spent years living out of a van, climbing mountains. One night, waiting for a jump, he told a story about a time he had to down-climb a two hundred-foot face without a rope. When someone asked how he didn’t panic, he said whenever he felt it coming on, he imagined the sound of a carabiner snapping shut.

Bernt didn’t see him again after Jump School. He’d heard the guy drove his van into the mountains after his discharge and swallowed a bottle of pills. But the click of the ASP always reminded Bernt of his imaginary carabiner. The sound of safety, he had called it.

Click below to pre-order your copy of Project Namahana, coming 06.28.22!

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

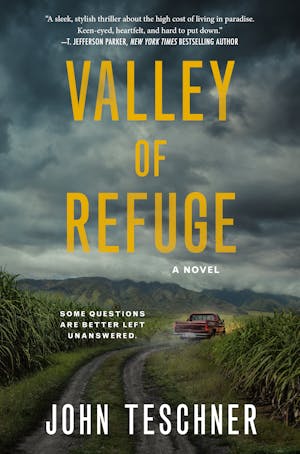

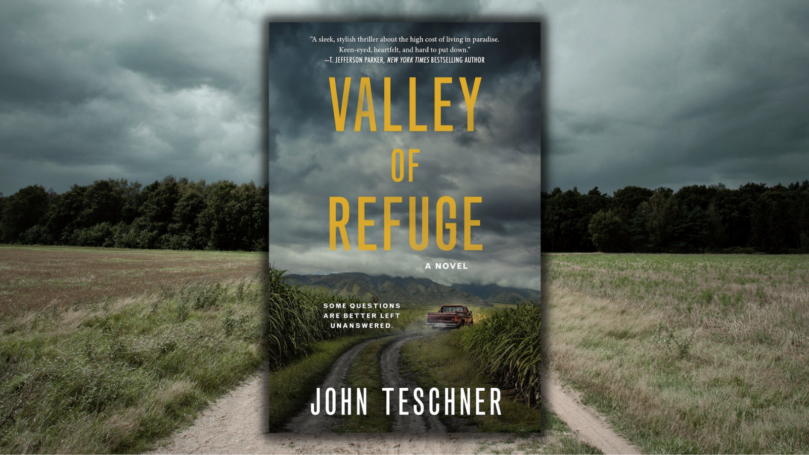

In this high-stakes, character-driven thriller, a Hawaiian family must decide the future of their ancestral land when a tech billionaire decides he wants it for himself, and won’t take no for an answer.

In this high-stakes, character-driven thriller, a Hawaiian family must decide the future of their ancestral land when a tech billionaire decides he wants it for himself, and won’t take no for an answer.

Micro by Michael Crichton and Richard Preston

Micro by Michael Crichton and Richard Preston