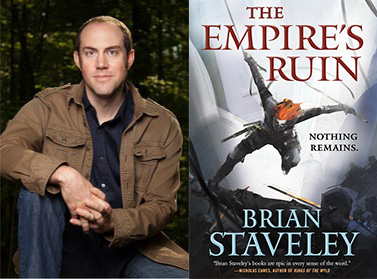

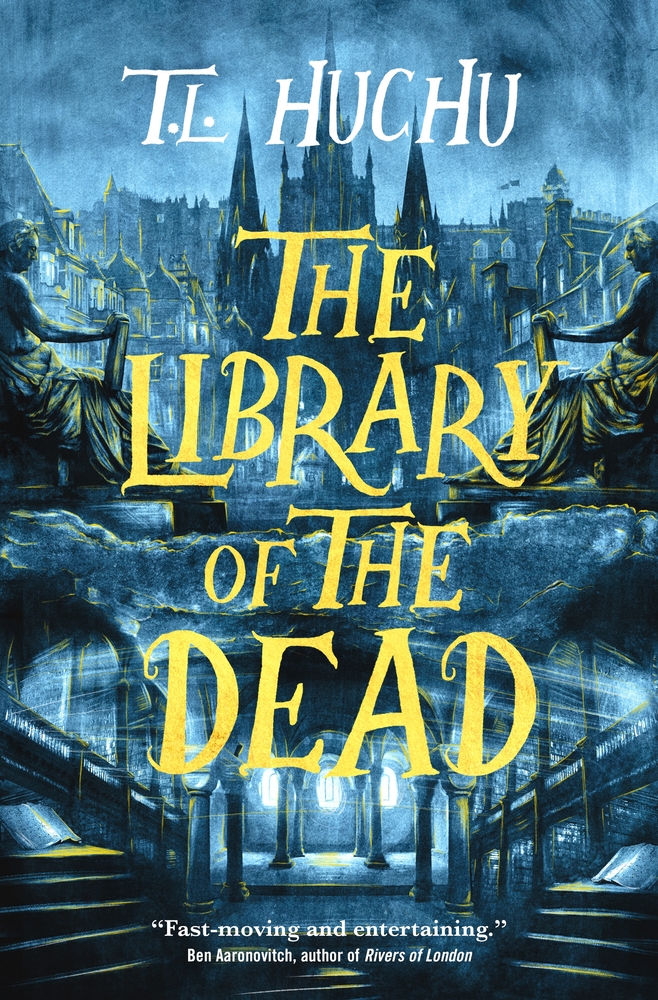

In The Grief of Stones, Katherine Addison returns to the world of The Goblin Emperor with a direct sequel to The Witness For The Dead…

In The Grief of Stones, Katherine Addison returns to the world of The Goblin Emperor with a direct sequel to The Witness For The Dead…

Celehar’s life as the Witness for the Dead of Amalo grows less isolated as his circle of friends grows larger. He has been given an apprentice to teach, and he has stumbled over a scandal of the city—the foundling girls. Orphans with no family to claim them and no funds to buy an apprenticeship. Foundling boys go to the Prelacies; foundling girls are sold into service, or worse.

At once touching and shattering, Celehar’s witnessing for one of these girls will lead him into the depths of his own losses.

The love of his friends will lead him out again.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of The Grief of Stones by Katherine Addison, on sale 06/14/22.

1

I slept patchily that night and woke to an overcast dawn; the light was gray and thin. I meditated, went to the public baths, then the Hanevo Tree, then up to the Prince Zhaicava Building and my cold, bare box of an office.

My post at that office, addressed to THE WITNESS FOR THE DEAD, was sporadic but often interesting—although “interesting” was a poor word for the letters I received, sometimes tragic, sometimes blackly comic, sometimes horrifying. There was one man who wrote to me every time someone drowned in the Mich’maika, claiming he had drowned them. I often received letters from people accusing their neighbors of murder, which required a great deal of tedious double-checking to prove wrong. And people wrote to me about ghosts and walking spirits and hauntings, which were almost always nothing of the sort, the exception being the people who wrote to me about the Hill of Werewolves, where the ghosts were genuine

This morning there was a letter from a scholar of the first rank. That was new, and I opened it warily

To Thara Celehar, prelate of Ulis and Witness for the Dead, greetings.

We are writing to ask of you a very peculiar favor. Our area of study is the dissolution of the Anmureise mysteries, and we have heard that the Hill of Werewolves is haunted, if that is the right word, by the purge of the Wolves of Anmura.

We are in ill health and cannot go explore the phenomenon for ourself, but we understand that you have witnessed it. Might you be willing to answer a few questions? You will find us in our workroom at the University most afternoons.

We sign ourself, with great respect,

Aäthis Rohethar

I considered this letter, somewhat blankly, for several minutes, before I decided that I had to answer it, for common politeness if nothing else.

I found ink and pen and paper and sealing wax and after some hesitation wrote,

To Aäthis Rohethar, scholar of the first rank, greetings.

It is true that we have witnessed the ghosts on the Hill of Werewolves, and we would be glad to answer any questions that we can. At the moment we are quite busy, but we will come to the University on our first free afternoon.

Respectfully,

Thara Celehar, Witness for the Dead

I sealed the letter, putting my lighter carefully back in my inner waistcoat pocket. My next step in finding Osmin Pavalo Temin required a visit to the postal service’s main office in any event.

I spent the rest of the morning, uninterrupted by petitioners, writing notes about the petition of the Marquess Ulzhavel and my investigation thus far, so that if I was called upon to give a judicial deposition, I would be able to assemble a coherent narrative of my witnessing.

Then I went to the postal service for help in finding Osmin Temin.

The Temada were such a minor house that I had never heard of them. I wondered if they even had an estate, or if they were what was called “town gentry” (something the Marquess Ulzhavel would never be, even though his compound was entirely encapsulated by the city of Amalo). Hence the postal service.

The central office of the Amalo Postal Service was housed in the Prince Thuvenis Building, of which it took up nearly half. It had once been a part of the Cartographers’ Guild, but those who wanted to do cartography found that they were spending most of their time on record-keeping and those who were interested in the grand logistical nightmare of delivering the post in a city the size of Amalo found that they were spending most of their time on map-drawing. The split, some twenty years ago, had allegedly been amicable, but the postal service did not use the Guild maps. They had their own, and it was the postal service’s maps that would show where the members of the House Temada lived.

The front office in the Prince Thuvenis Building had a young goblin woman at a desk to one side and a row of post collection boxes to the other. After I had put my letter in the appropriate box, I crossed to her desk. It took her a moment to realize that I was actually approaching her.

“Oh! Good morning, othala! May we help you?”

“We are Thara Celehar, a Witness for the Dead. We need to find the House Temada.”

“Just a moment.” She got up and disappeared through a discreet door among the wall hangings behind her desk. It was longer than “a moment,” but not as much as ten minutes before she returned, accompanied by an elderly elven man whom she introduced as a senior clerk of the postal service.

He and I exchanged bows, and he said, “You are looking for the Temada.”

“Yes,” I said. “Our witnessing requires it.”

“The postal service is under no obligation to help you,” he said sharply.

“Not at all,” I said and wondered if he was going to seek the satisfaction of being disobliging just because he could.

But apparently he had only wanted to make it clear where he stood, for he said, “Their compound is in the Tobazran district. First stop past the Mountain Gate on the Cevoro line. Then you follow the tram line for two blocks, and you’ll find the Temada on your right. There is only the one door in that wall.”

“You sound as though you’ve been there,” I said.

He smiled slightly. “On your left, you’ll find Tobazran Post Office Number Three, where we worked for many years.”

“Of course,” I said. “Thank you.”

“The postal service is here to help, othala,” he said, and we bowed to each other again.

I walked to the Dachenostro to board the first tram I saw that was taking the Cevoro line. At the first stop after we rattled through the Mountain Gate, I disembarked and found myself in an obviously well-to-do neighborhood of shops and small apartment buildings nothing like the tenement I lived in. I walked north two blocks, following the tram line, and as the clerk had said, there was only one door in the block-long wall on my right.

There was a crest on the door, two swans back-to-back, their necks intertwined. Presumably the Temada’s crest—I did not recognize it.

There was a bell rope beside the door. I pulled it firmly and then waited for what seemed like a very long time. Finally, the door was opened by a puzzled-looking elven woman in green-and-gold livery. “Can I help you, othala?”

“I am Thara Celehar, a Witness for the Dead. I am looking for Osmin Pavalo Temin.”

“Well, you won’t find her here,” the woman said. “Osmer Temar won’t even have her mentioned.”

“Oh dear,” I said, with a pang of sympathy for Osmin Temin. “Do you have any idea of where she might be?”

“The last we heard, she’d started some sort of school in Cemchelarna. But that was two years ago. Maybe more. I’m sorry, othala.”

Two years ago made it after she’d been forced to resign from the foundling school board, so either she had some new venture in Cemchelarna or the woman’s information was muddled and out of date. Either seemed plausible.

“Thank you,” I said. “That is very helpful.”

“Be careful, othala,” she said as she closed the door, leaving me unsettled as well as thwarted. But there was nothing for it except to go back the way I had come and try again with the postal service.

The same young goblin woman was still at the desk when I returned. “Did you not find her, othala?”

“No,” I said. “We are told she might be in Cemchelarna. Could someone consult the postal registers and look for Pavalo Temin?”

“We will find out,” she said and disappeared again through the discreet door in the wall behind her.

I waited.

She was gone for a long time, long enough that I began to worry I had gotten her in some kind of trouble. But she came back as serenely as she had gone and handed me a slip of paper, on which was written in an exquisitely legible hand Cemchelarna Post Office Number Five, Goshawk Street.

“That’s where she’s registered, othala. Mer Aivonezh says that’s the most help we can give you.”

“Thank you,” I said. “This is very helpful indeed.”

She smiled and said, “Good luck, othala.”

“Thank you,” I said. I left, almost clutching the slip of paper, to get the cartography clerks to tell me where Goshawk Street was.

One of the cartographers, a young elven man whose name I had forgotten, was in the front office when I came in, bent over a map with a pair of calipers. He said, “Hello, othala,” without straightening. Min Talenin, a good bourgeois elven spinster, turned from her filing cabinets and said, using the plural “we,” “Good afternoon, othala. Can we help you?”

“Good afternoon, Min Talenin. Yes, I need to find the post office on Goshawk Street in Cemchelarna.”

“A post office!” she said. “Then that is an easy question, for we mark the post offices on our maps. Here.” She unrolled a map across her desk, weighting it with an inkwell, a lamp, and two iron pyramids that I recognized as apothecary’s weights. “This is the eastern half of Cemchelarna. So Goshawk Street . . . no, not there . . . not there . . . it’s in this cluster of bird names. There!” She indicated a line on the map with her forefinger; I saw the tiny blue star representing the post office. “And to get there, you’ll want to cross the Abandoned Bridge and keep going on what turns into Lacemaker Street. Follow Lacemaker Street to a cross street called Pigeon Street, turn south, go two blocks, and then an alley on your left will lead to Goshawk Street. The post office should be three blocks south on your left.”

“Thank you, Min Talenin,” I said, scribbling directions in my notebook. “As always, you are a tremendous help.”

She smiled and said, using the plural, “We are always happy to help you, othala.”

I bought lunch from a street vendor and ate while I walked. Lacemaker Street twisted and turned a good deal, and after a few blocks I had to stop and check every cross street to see if it was Pigeon Street, since I had no good sense of how much real territory was covered by an inch on the cartographers’ maps. Many cross streets were not labeled at all, but finally I came to one where the street sign, bolted firmly to the wall of the corner shop, said PIGEON STREET. I turned south and walked two blocks, then scanned the row of houses to my left, looking for an alleyway. At first I didn’t see it, but then I realized that the gap between a blue clapboard house and a green clapboard house had to be what Min Talenin had generously described as an alley. It was almost exactly the width of my shoulders and it curved first one way and then the other around the shapes of the houses.

I edged through it, taking almost breath-held care to keep my silk coat of office from snagging on anything. On the other side, hopefully on Goshawk Street, I walked three blocks south and was greeted with a blue sign reading CEMCHELARNA POST OFFICE NO. 5 on a gray brick of a building. Inside, like most post offices, they had a list of registrants on a chalkboard. I skimmed the list and was relieved to find the name Pavalo Temin, and underneath it CEMCHELARNA SCHOOL FOR FOUNDLING GIRLS.

A part-goblin clerk leaned across the counter and said, “Can I help you, othala?”

“Yes,” I said and followed his lead on formality. “I am Thara Celehar, a Witness for the Dead. I’m trying to find the Cemchelarna School for Foundling Girls.”

“Couldn’t be easier,” said the clerk. “One block south, on your right. There’s a sign.”

“Thank you,” I said. Now—after all the seeking back and forth—to find out if this was indeed the Osmin Pavalo Temin who had a reason to hate the Marquise Ulzhavel.

The school was a large dormered brick building with a crisp black-on-white sign. I climbed the stairs and pulled open half of the double doors. The inner doors of the narrow foyer were locked, but there was a bell pull. I rang the bell, and after a surprisingly lengthy pause, an elven girl came running down the stairs and unlocked the inner doors.

She was thirteen or fourteen, plain-faced but with strikingly clear blue eyes. She was not all that much younger than Isreän had been, and she seemed scared, her ears almost flat to her head. She was wearing what looked like a uniform, an unbleached linen pinafore over a long-sleeved gray dress. Her hair was in two long plaits, children’s plaits although she was old enough to start pinning her hair up.

She bobbed me a curtsy and said, “Please, othala, Osmin Temin says I must ask your name and business.”

My formality had to be dictated by my errand. I said, “We are Thara Celehar, a Witness for the Dead, and we must speak to Osmin Temin.”

She looked even more scared, but she nodded and said, as she’d obviously been told to say, “If you will wait here, please.”

“Of course,” I said. She ran back up the stairs, and I looked around. It was a square room with lovely wood paneling; the staircase followed the walls around, with a broad landing just opposite the front doors, and above the landing was a large multipaned window with a pattern in stained glass as a border; it must have cost the building’s first owner a small fortune. The carpet was also beautiful, although old and worn.

The elven girl came back down the stairs, sedately this time, and said, “Please, othala, Osmin Temin will see you. If you will follow us?”

I followed her up the stairs. The second floor was two long hallways stretching out from the stairhead; my guide turned left, and we walked about halfway down the hall before she knocked at one of the doors.

“Come in!” called a woman’s voice; the girl opened the door and bowed for me to enter.

Osmin Pavalo Temin was a middle-aged elven lady, beautifully dressed and perfectly coiffed, with long tashin sticks like daggers through the bun at the back of her head. There was nothing remarkable about her face, except perhaps for a certain hardness in her eyes. I disliked her instantly and powerfully.

She inclined her head in something that was not quite a bow. “Othala. Your presence is an honor. How may we help you?”

I said, “We are Thara Celehar, a Witness for the Dead. We are witnessing for Tomilo Ulzhavel. We understand that you knew her?”

“Knew her?” Osmin Temin looked bewildered, but I could not tell if it was genuine or not. “We served on a foundling school board with her, five years ago, but that is barely more than an acquaintance.”

“We understand that you had a serious disagreement with her,” I said.

“Oh,” she said, her eyes narrowing. “We begin to understand. Someone has a busy tongue.”

“We are investigating the possibility she was murdered.”

“And what do you expect from us, othala? A confession?”

“If you happen to have killed her, yes, that would save us a good deal of time and bother.”

Her laugh was more like a snarl. “We didn’t kill her. What good would it have done us? Now, if you don’t mind—”

There was a knock at the door.

“Come in!” Osmin Temin said, probably louder than was necessary

The door opened, and a part-goblin girl came in, wearing the same uniform as the elven girl who had answered the door, with her hair in those two long plaits, although this girl was even older, maybe as old as sixteen, which was old enough to leave school. She, too, looked scared. She came up beside me and curtsied to Osmin Temin. “Please, osmin, Min Tesavin needs you downstairs.”

Her foot brushed mine. Glancing down, I saw a piece of paper folded down to almost nothing on the floor between us. I moved the toe of my shoe to cover it. I did not look at the girl.

“Blessed goddesses, what is it this time?” Osmin Temin moaned to the ceiling.

The girl said, “I don’t know, osmin. Just that it’s important.”

“It’s always important with Min Tesavin,” Osmin Temin said. “Othala, if you will excuse us, we have a school to run.” Her tone indicated she was done with our conversation; I had no reason to argue with her.

“Of course, osmin,” I said. “Thank you for your help.”

She glared at me in passing; then she was gone, the girl obedient in her wake. I retrieved the paper and tucked it safely in my inside coat pocket, then stepped into the corridor. An elven girl walking alone glanced up and then quickly looked down, hunching her shoulders and speeding up. I found my way back to the stairs and gratefully left.

I did not stop to unfold the paper until I was back at the Abandoned Bridge. It read:

PLEASE HELP US

STOP THEM

Copyright © 2022 from Katherine Addison

Pre-Order The Grief of Stones Here:

by Kevin J. Anderson

by Kevin J. Anderson by Brian D. Anderson

by Brian D. Anderson A Chorus of Dragons series by Jenn Lyons

A Chorus of Dragons series by Jenn Lyons The Serpent Gates duology by A. K. Larkwood

The Serpent Gates duology by A. K. Larkwood The Lotus Kingdoms trilogy by Elizabeth Bear

The Lotus Kingdoms trilogy by Elizabeth Bear by Ryan Van Loan

by Ryan Van Loan by Kit Rocha

by Kit Rocha The Mystic Trilogy by Jason Denzel

The Mystic Trilogy by Jason Denzel by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson

by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson by Brandon Sanderson

by Brandon Sanderson

Legends & Lattes

Legends & Lattes The Goblin Emperor

The Goblin Emperor The House in the Cerulean Sea

The House in the Cerulean Sea Winter’s Orbit

Winter’s Orbit Victories Greater Than Death

Victories Greater Than Death

The Locked Tomb Series

The Locked Tomb Series

Under the Whispering Door

Under the Whispering Door

The Grief of Stones

The Grief of Stones In the Shadow of Lightning

In the Shadow of Lightning Daughter of Redwinter

Daughter of Redwinter Sands of Dune

Sands of Dune Flying the Coop

Flying the Coop The Albion Initiative

The Albion Initiative The Memory in the Blood

The Memory in the Blood Mythago Woods

Mythago Woods Just Like Home

Just Like Home

Three Miles Down

Three Miles Down The Eye of Scales

The Eye of Scales The Book Eaters

The Book Eaters Full House

Full House Councilor

Councilor

Dance with the Devil

Dance with the Devil

In The Grief of Stones, Katherine Addison returns to the world of The Goblin Emperor with a direct sequel to The Witness For The Dead…

In The Grief of Stones, Katherine Addison returns to the world of The Goblin Emperor with a direct sequel to The Witness For The Dead…

Stygian

Stygian

The Echo Wife

The Echo Wife The Goblin Emperor

The Goblin Emperor

Lizzy Hosty, Marketing Intern (she/her)

Lizzy Hosty, Marketing Intern (she/her) Desirae Friesan, Publicist (she/her)

Desirae Friesan, Publicist (she/her) Samantha

Samantha  a cat, Marketing Coordinator (he/him)

a cat, Marketing Coordinator (he/him) Julia Bergen, Marketing Manager (she/her)

Julia Bergen, Marketing Manager (she/her) Yvonne Ye, Ad/Promo Assistant (she/her)

Yvonne Ye, Ad/Promo Assistant (she/her) Rachel Taylor, Marketing Manager (she/her)

Rachel Taylor, Marketing Manager (she/her) Kaleb Russell, Marketing Assistant (he/him)

Kaleb Russell, Marketing Assistant (he/him)

Gideon the Ninth

Gideon the Ninth