Lady Hotspur author Tessa Gratton is no stranger to adapting Shakespeare. She took on King Lear in her 2018 novel The Queens of Innis Lear, and with Lady Hotspur, she’s taken on Henry IV, Part I. Tessa joined us to talk adaptations, queer reimaginings, and her unconventional favorite Shakespeare play.

By Tessa Gratton

I’v e been obsessed with Prince Hal and his mirror/foil Hotspur ever since I studied Henry IV, Part I in a college class called “Weird Shakespeare” during my freshman year in 2000. For the final, another young woman and I performed their confrontation—broadswords and all. I played Hal—playful, self-loathing, ambitious Hal—and he’s never left me.

e been obsessed with Prince Hal and his mirror/foil Hotspur ever since I studied Henry IV, Part I in a college class called “Weird Shakespeare” during my freshman year in 2000. For the final, another young woman and I performed their confrontation—broadswords and all. I played Hal—playful, self-loathing, ambitious Hal—and he’s never left me.

I’ve gone through phases where my obsession shifted to the forthright, blustering warrior Hotspur, or Hotspur’s sharp, passionate wife Kate Percy, and have taken every opportunity to see performances of Part I in particular, though any of the Henriad will do it for me. I’ve liked to imagine different endings to the play, wondered what would have changed had Hal and Hotspur met before the battle that destroyed Hotspur, or how Lady Percy might’ve acted to shift the arc of the story. I imagined Hal and Hotspur childhood lovers, now made enemies for the sake of their kingmaker fathers. Over the years I sought out some fanfic to read, toyed with rewriting scenes myself, and assumed someday I’d make a novel of my obsessions.

After finishing The Queens of Innis Lear, my feminist fantasy adaptation of my least favorite Shakespeare play, I was finally ready to adapt my most favorite Shakespeare play, and one thing was immediately obvious: Hal and Hotspur would be women, and lovers, and maybe I could take everything that I loved in the play and, well, make it gayer.

When writing a queer adaptation, the first thing I do is dig into the source material to find the queer space and threads of queerness that are already present. As it turns out, a lot of analysis of Henry IV, Part I includes queer readings, though not always overtly, or even intentionally. When you look at queer space as liminal space, and how space itself can be queered, you don’t even have to consider sexual desire or gender to find a queer reading.

The play is the story of Prince Hal, a reluctant heir to the throne, dragging himself out of the gutter to take up his father’s mantle and defeat the rebellious Hotspur. Hal exists in three spaces: the court, the taverns, and the countryside, each ruled by another character. His father, the king, represents court and chivalry, familial duty, and secularism. Falstaff, the drunken, fat former knight, represents the taverns and debauchery, survival, brotherhood, and importantly, imagination and humor. Hotspur represents the old world where the lord and land are one, and the more ancient religious kinds of duty and the chivalry of nature.

Hal was born into the court, fled to the taverns, and must confront the old world before he can triumph as a prince and earn his eventual crown. As a character he exists between these spaces, in the shadows, a trickster who alone has the capacity to go from debauchery to chivalry and back, from play to duty and back, and combine the skills he learns in each space to better perform in the others. His success at learning to maneuver through different spaces is shown when he superimposes the worlds of court and tavern over each other in the scene where he and Falstaff act out Hal’s meeting with the king, trading roles and jokes, and in that moment of queered space Hal is able to tell Falstaff a single true thing about their future; later, just before fighting Hotspur, Hal says to his rival, “all the budding honors on thy crest I’ll crop to make a garland for my head.” He will take onto himself everything that Hotspur was, by confronting and killing him. He will become Hotspur, taking over his space and triumphant identity.

This is just one possible queer reading of Hal, but it’s one I like because I’m interested in carving queer space within existing power structures, and so I used this reading specifically in developing my adaptation. Additionally, since I was setting the story in the same world as The Queens of Innis Lear, I also knew I wanted to use themes I’d begun pulling apart in my King Lear adaptation to continue investigating connections between power, patriarchy, and rebellion, and nature, relationships, and magic.

Except this time, I was going to center queer narratives.

That became my foundational goal: to adapt Henry IV, Part I with an eye toward integrating queer lives into narratives of power.

First of all, I took the men in the play and made them women or pushed them a lot closer toward woman on the gender spectrum, and did the reverse for the few women in the source material. Second, I gave nearly all the main characters some variety of queer desire.

When it came to building my world and story so that I could focus on queering narratives and structures of power, I returned to the queer analysis of Prince Hal as a trickster moving between spaces. My Hal is a young cis lesbian desperately in love with the bright warrior woman Hotspur, but she doesn’t know how to be what her mother needs her to be for the stability of their new order, nor can she remain debauched in the shadows with her Falstaff—Oldcastle, in my version.

I kept two of the three spaces central to the play: court and taverns. The court is ruled by Hal’s mother the queen, who struggles to maintain a traditional, secular patriarchy when she herself has rebelled against it and has been betrayed by it, because she can’t imagine any other kind of power structure. The taverns are ruled by Lady Ianta Oldcastle, a lesbian and former-knight who has also been betrayed by those same power structures that harmed the queen. Ianta encourages debauchery and small playful rebellions because she no longer believes there is space for queer women in the halls of power, so queer women should focus on survival and find pleasure where and how they can.

But the third space is not merely the old world, the landscape, it is the island of Lear. For a hundred years power on Innis Lear has existed in direct opposition to Hal’s country Aremoria: on Innis Lear they do not rely on that old heteronormative institute of marriage for their lines of succession; their magic comes from a wilder, freer union between earth and wind and stars; genderfluid witches care for the forests; the dead are caught between life and heaven; the current rulers include a queen and her sister, an openly queer crown prince, and a transgender princess.

These are the landscapes Hal must map out for herself in my adaptation, must learn to commune with, finding ways to be herself, carving space for her friends and loved ones to claim identities outside the traditionally accepted without giving up any her/their power. It isn’t an option for her to burn everything down, but she is uniquely positioned to reframe the narrative of her entire country, if she can survive with her heart intact.

Lady Hotspur is a big, sprawling fantasy that delves in to the relationships and humor and politics of Henry IV, Part I that obsessed me for nearly twenty years. But throughout every round of writing and revision I tried to keep that core tension present: Hal and Hotspur loving and hating and loving and fighting each other. In the original text, Hal says to Hotspur that he will take everything Hotspur was and make it part of himself through necessary violence; in my adaptation, Hal says to her Hotspur, “What if I love you so well it changes the very landscape of our world?”

Both of these positions have a different relationship with power: one is patriarchal and consuming and violent; the other is queer and creative and playful. It’s that difference in approaches to power and the tension of possibility created in their clashing that is at the heart of what I was trying to do by centering queerness in my adaptation.

I hope I at least succeeded in writing a dramatic, wild, and passionate story that engages with the source material in new ways. It’s amazing to me that after twenty years of thinking about a four-hundred-year-old play I can still find so many threads and spaces to pull or inhabit, but I’m happy to be part of the long story of Shakespeare’s plays and what keeps them alive through new interpretations.

Order Your Copy of Lady Hotspur:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Lady Hotspur by Tessa Gratton

Lady Hotspur by Tessa Gratton opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Flint & Mirror by John Crowley

Flint & Mirror by John Crowley opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

The Whispering Swarm by Michael Moorcock

The Whispering Swarm by Michael Moorcock opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

She Who Became the Sun

She Who Became the Sun

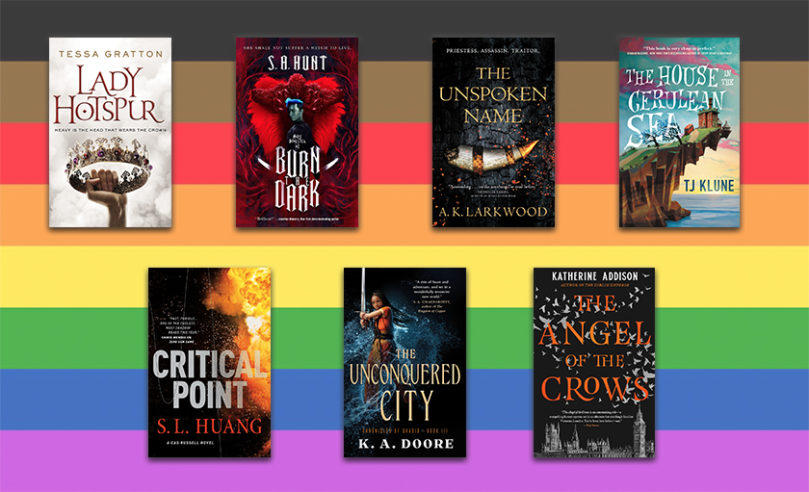

Lady Hotspur

Lady Hotspur

The Unspoken Name

The Unspoken Name

Critical Point

Critical Point

We are so incredibly, over-the-top, crazy-in-love with

We are so incredibly, over-the-top, crazy-in-love with

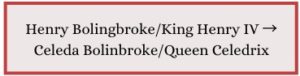

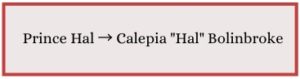

Henry IV’s heir who hangs out with drunks and thieves, but says it’s part of a plan to stun people with how kingly and capable he is later is turned into

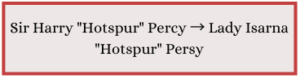

Henry IV’s heir who hangs out with drunks and thieves, but says it’s part of a plan to stun people with how kingly and capable he is later is turned into  The famous knight, and leader of the English rebel forces against King Henry, with very poor impulse control is turned into Lady Hotspur, a famous knight with a hot temper, and part of Celeda’s rebellion. She is heir to the earldom of Perseria.

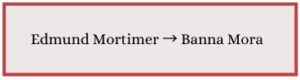

The famous knight, and leader of the English rebel forces against King Henry, with very poor impulse control is turned into Lady Hotspur, a famous knight with a hot temper, and part of Celeda’s rebellion. She is heir to the earldom of Perseria. The man who was heir to the deposed Richard II is turned into Banna Mora, a young woman who was

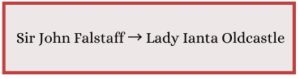

The man who was heir to the deposed Richard II is turned into Banna Mora, a young woman who was  Prince Hal’s surrogate father in the tavern world, a big-time drunk, cheat, thief, and scoundrel is turned into Lady Ianta Oldcastle, the

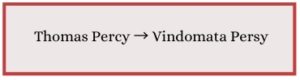

Prince Hal’s surrogate father in the tavern world, a big-time drunk, cheat, thief, and scoundrel is turned into Lady Ianta Oldcastle, the  The Earl of Worcester, Hotspur’s uncle and fellow rebel leader is turned into Duke Vindomata of Mercia, Lady Hotspur’s aunt and a part of Celeda’s rebellion. Vindomata is known as the King-Killer.

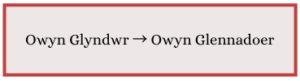

The Earl of Worcester, Hotspur’s uncle and fellow rebel leader is turned into Duke Vindomata of Mercia, Lady Hotspur’s aunt and a part of Celeda’s rebellion. Vindomata is known as the King-Killer. The leader of Welsh rebels, father of Lady Mortimer is turned into the

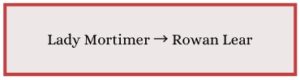

The leader of Welsh rebels, father of Lady Mortimer is turned into the  Owyn Glyndwr’s daughter is turned into Prince Rowan,

Owyn Glyndwr’s daughter is turned into Prince Rowan,