ONE

Life as a lady—A lecture at Caffrey Hall—My husband’s student—The state of our knowledge—Suhail’s theory— A foreign visitor

Members of the peerage, I need hardly tell you, are not always well behaved. Upon my ascension to their ranks, I might have become dissolute, gambling away my wealth in ways ranging from the respectable to quite otherwise. I might have ensconced myself in the social world of the aristocracy, filling my days with visits to the parlours of other ladies and the gossip of fashion and scandal. I might, were I a man, have involved myself in politics, attempting to carve out a place in the entourage of some more influential fellow.

I imagine that by now very few of my readers will be surprised to hear that I eschewed all these things. I have never been inclined to gamble (at least not with my money); I find both fashion and scandal to be tedious in the extreme; and my engagement with politics I have always limited as much as possible.

Of course this does not mean I divorced myself entirely from such matters. It would be more accurate to say I deceived myself: surely, I reasoned, it was not at all political to pursue certain goals. True, I lent my name and support to Lucy Devere, who for years had campaigned tirelessly on behalf of women’s suffrage, and I could not pretend anything other than a political motive there. My name carried a certain aura by then, and my support had become a meaningful asset. After all, was I not the renowned Lady Trent, the woman who had won the Battle of Keonga? Had I not marched on Point Miriam with an army of my own when the Ikwunde invaded Bayembe? Had I not unlocked the secrets of the Draconean language, undeciphered since that empire’s fall?

The answer to all these things, of course, was no. The popular narrative of my life has always outshone the reality by rather a lot. But I was aware of that radiance, and felt obliged to use it when and where I could.

But surely the other uses to which I put it were only scholarly. For example, I helped to found the Trent Academy for Girls in Falchester, educating its students not only in the usual female accomplishments of music and literature, but also in mathematics and various branches of science. When Merritford University began awarding the first degrees in Draconic Studies, I was pleased to endow the Trent Chair for that field. I contributed both monetary and social support to the International Fraternity for Draconic Research, an outgrowth of the work Sir Thomas Wilker and I had begun at Dar al-Tannaneen in Qurrat. Less formally, I encouraged the growth of the Flying University until it formed a network of friendships and lending libraries all across Scirland, catching in its net a great many people who would otherwise not have had access to such educational opportunities.

Such things accumulate, bit by bit, and one does not notice until it is too late that they have eaten one’s life whole.

On the day that I went to attend a certain lecture at Caffrey Hall, I was running behind schedule, which had become the common state of my life. Indeed, the only reason I did not miss it entirely was because I had purchased a clock of phenomenal ugliness, whose sole virtue—most would call it a flaw—was its intolerably loud chiming. This was the only force capable of rousing me from my haze of letter-writing, for our butler had recently joined the army, our housekeeper had left us to care for her elderly mother, and I was not yet on good enough terms with their replacements to rely on them to evict me from my study by force.

But they had the carriage waiting when I came flying down the stairs, and in short order I was on my way to Caffrey Hall. At the time I was grateful because I would have been sorely disappointed to miss the lecture. In hindsight, I would have missed out on a great deal more.

The crowd on the street outside was large enough that I directed my driver around the corner, where I disembarked and entered the hall by a side entrance. This deposited me much closer to my first port of call, which was a room near the lecture hall proper. I pressed my ear to the door and heard a voice murmuring inside, which warned me not to disturb him by knocking. Instead I eased the door open and slipped quietly through.

Suhail was pacing a narrow circuit across the floor, sheaf of papers in one hand, the other fiddling with the edge of his untied cravat as if it were a headscarf, muttering in a low, quick voice. It was his habit before any lecture to make one final pass through his points. When he saw me, though, he stopped and took out his pocket watch. “Is it time?”

“Not yet,” I said. One could not have guessed it by the hubbub, which was audible even through the door. “I am dreadfully late, though. There was a new report from Dar al-Tannaneen.”

This was the home of the International Fraternity for Draconic Research, and the report concerned the honeyseeker breeding effort, which was establishing the boundaries of developmental lability. Tom Wilker and I had discovered that principle quite by accident during our time there, while trying to determine how much environmental variation a draconic egg could endure without aborting or producing a defective organism; further research had confirmed that the issue was not so much defectiveness as mutation, which (when successful) adapted the resulting creature to its expected environment.

Of course the theory was not yet widely accepted. No such theory ever is: it has taken an astonishingly long time for the concept of germs to catch on, even though it has the benefit of saving lives. I cannot claim any such grand result for my own theory. But slowly, one generation of honeyseekers at a time, the Fraternity’s work was laying a foundation even the most skeptical of critics could not assail.

Suhail’s expression lightened into a smile. “I would say I am surprised…”

“… but it would be a lie. They have a new idea for how to encourage the growth of larger honeyseekers. I had to read it, and see if I could offer any suggestions. Speaking of which: is there anything you need, before you throw yourself to the wolves?”

He turned to lay the papers he held in a leather folder, lest his hand render them sweaty and crumpled. “I think it is beyond even your tremendous capabilities to produce a second Cataract Stone for me, which is what I most truly need.”

A second such artifact might exist; but we had been lucky even to find the first, and could not count upon a repeat of that good fortune. The Cataract Stone, which I had stumbled across in the jungles of Mouleen, was that most precious gift to linguists, a bilingual text: its upper half was written in the indecipherable Draconean script, and its lower half in the much more decipherable Ngaru. Proceeding from the assumption that the two halves contained the same text, we had, for the first time, been able to discover what a Draconean inscription said.

Being not a linguist myself, I had, in my naivete, assumed that would be enough—that with the door thus opened, the Draconean language would promptly unfold its secrets like a flower. But of course it was not so simple; we could not truly read the Cataract Stone. We only knew what it said, which did not assist us in deciphering any other text. It gave us a foothold, nothing more.

And while a foothold was a good deal more than we’d had in the past, it provided only a narrow place to stand while searching for the next step. Suhail lifted one hand to run it through his hair, then realized he would disarrange it, and put his hand back down again. “Without a more certain framework for the entire syllabary,” he said, “much of what I have to say today is guesswork.”

“Highly educated guesswork,” I reminded him, and reached out to tie his cravat. He did not need me to do so for him; when he began to adopt Scirling dress, he swore he would not be the sort of aristocrat who could not even tie his own cravat. Nor, of course, did he favour the elaborate knots and folds so beloved of my nation’s dandies in those days. Still, there was a simple pleasure in undertaking that task, feeling the rise and fall of his breath as I folded the cloth and pinned it into place.

“But guesswork nonetheless,” he said as I worked.

“If you are wrong, then we will know it in time; the hypothesis will not hold up. But you are not wrong.”

“God willing.” He laid a kiss on my forehead and stepped back. In a Scirling frock coat or an Akhian caftan, my husband cut a fine figure—especially at moments like these, when his thoughts were bent to matters academic. Some ladies’ hearts are captured by skill at dancing, others by poetry or extravagant gifts; it will surprise no one that I was taken in by his keen mind.

“You have a substantial crowd waiting for you,” I said, as the noise from outside continued to rise. “If it is all the same to you, I will take a seat at the back, so that others will have a better view.” I’d already enjoyed a private box for the development of his ideas, of which this was only the public revelation. Given the size of the waiting audience, I suspected more than a few people would be standing for the duration of his lecture, and I would gladly have ceded my chair to another; but being a peer, and a lady besides, I knew I would never succeed. The best I could hope for was to displace some fit young fellow, rather than an older gentleman who needed the seat far more than I.

Suhail nodded, distracted. He was always like this before a lecture, and I took no offense. “Then I will see if Miss Pantel needs anything,” I said, and slipped back out of the room.

I could hear chanting outside, with a distinctly unfriendly tone. The rise of interest in Draconean matters had sparked a concomitant rise in Segulist zealotry, which decried our newfound obsession with the pagan past. Suhail’s lecture was likely to inflame them more. Fortunately, the manager of Caffrey Hall had taken the precaution of hiring men to stand guard at the doors, and the worst of the rabble-rousers were kept outside.

That still left a great many people inside the building. The decipherment of the Cataract Stone and the discovery of the Watchers’ Heart in the depths of the Akhian desert had sparked a fad for that ancient civilization, with a great many cheap books of dubious accuracy or academic worth being published on the subject, and Draconean motifs becoming popular in everything from fashion to interior decoration. Earlier that same week, the poet Peter Flinders had sent me a copy of his epic poem Draconis, in the hope that I might endorse it.

But even in the depths of such a craze, historical linguistics is a sufficiently abstruse topic that it attracts a more limited audience, of (dare I say) a more elevated class. I do not necessarily mean birth or wealth: I saw men there who would never have been permitted into the august halls of the Society of Linguists. They had a serious look about them, though, as if they knew at least a little concerning the topic, and were eager to learn more.

It was a mark of how much Scirling society had changed since my girlhood that I was not the only woman there. Even in sedate afternoon dresses, the members of my sex stood out as bright spots amid the dull colours of the men’s suits, and there were more such spots than I had anticipated. There have been lady scholars for centuries, of course; the change was that they were finally out in public, rather than reading the articles and books alone in their parlours, or in the company of a few like-minded friends.

One such lady was on the stage, adjusting the placement of the large easel that would hold the placards illustrating Suhail’s argument. A goodly portion of the scandal that once attached to myself and Tom Wilker had moved on to Erica Pantel and my husband; there were far too many people who could not believe a man might take a young woman as his student, and mean the word as something other than a euphemism. I had lost count of the number of times someone implied within my hearing that I must be terribly jealous of her—especially as I was getting on in years, being nearly forty myself.

This troubled me very little, at least for my own sake, as I knew how false those rumours were. Not only did Suhail have little interest in straying, but Miss Pantel’s heart was already spoken for, by a young sailor in the Merchant Navy. They were madly in love and had every intention of marrying when he returned from his current voyage. In the meanwhile, she occupied herself with her other passion, which was dead languages. Her attachment to Suhail sprang from his familiarity with the Draconean tongue, and nothing else. Our fields of study might differ, but I considered her a fellow-traveller on the roads of scholarship; she reminded me a little of myself in my youth.

“Is everything in order?” I asked her.

“For now,” she said, with a meaningful glance toward the audience.

The manager of Caffrey Hall might be keeping the obvious rabble-rousers outside, but I had no doubt a few would slip into the building. And even those who came for scholarly reasons might find themselves incited to anger, once they heard what Suhail had to say.

I said, “I meant with the placards and such.”

“I know,” she said, flashing me a brief smile. “Is Lord Trent ready?”

“Very nearly. Here, let me help you with that.” The placards had to be large, in order to be at all visible from the back of the hall; the carrying-case Miss Pantel had sewn to hold them was almost as large as she, for my husband’s student was a diminutive woman. Together we wrestled the case into position and unbuckled its straps. She had cleverly stacked the placards so they faced toward the wall, with the first card outermost, which meant we need not fear anyone catching an advance peek at Suhail’s ideas.

Unless, of course, someone were to come up and rifle through them. Miss Pantel nodded before I could say anything. “I will guard them with my life.”

“I doubt that shall be necessary, but I thank you all the same,” I said with a laugh. No dragon could be a fiercer guardian. “If you don’t need anything further from me, I shall go play hostess.”

I meant the phrase as a euphemism. Necessity had taught me to be a hostess in the usual sense, though I still vastly preferred a meeting of the Flying University to a formal dinner. A baroness does have certain obligations, however, and although in my youth I would have thrown them off as useless constraints, in my maturity I had come to see the value they held. All the same, my true purpose in circulating about the hall and the lobby was to take a census of men I expected to cause trouble. I made particular note of a certain magister, whose name I shall not disclose here. If his past behaviour was any guide, he would find something to argue about even if Suhail’s lecture concerned nothing more substantive than the weather—and my husband would be giving him a good deal more fodder than that.

When it was time for the lecture to begin, I dawdled in the lobby for as long as I could. By the time I entered the main hall, every seat was filled, and people lined the walls besides. Despite my best efforts, however, my attempt to discreetly join the gentlemen at the back wall failed as expected. The best I could do was to accept the seat offered to me by a fellow only a little older than myself, rather than the venerable gentleman who was eighty if he was a day.

Following a short introduction by the president of the grandly named Association for the Advancement of Understanding of the Draconean Language, Suhail took the stage, to a generous measure of applause. Our discovery of the Watchers’ Heart (not to mention our romanticized wedding) had made him famous; his scholarly work since then had made him respected. It was not interest in Draconeans alone that brought such a large audience to Caffrey Hall that afternoon.

Suhail opened his speech with a brief summary of what we knew for certain, and what we guessed with moderate confidence, regarding the Draconean language. Had he been speaking to the Society of Linguists, such an explanation would not have been necessary; they were all well familiar with the topic, as even those who previously showed no interest in it had taken it up as a hobby after the publication of the Cataract Stone texts. But the Society, being one of the older scholarly institutions in Scirland, showed a dismaying tendency to sit upon information, disseminating it only by circulars to their members. Suhail wished the general public to know more. After all, it was still very much the age of the amateur scholar, where a newcomer to a field might happen upon some tremendous insight without the benefit of formal schooling. Suhail therefore delivered his lecture to the world at large, some of whom did not know declensions from décolletage.

It began with the portion of the Stone’s Ngaru text that gave a lineage of ancient Erigan kings. This was of some interest to scholars of Erigan history, and of a great deal more interest to linguists, for proper names are much more likely than ordinary words to be preserved in more or less the same form from one language to the next. The names of the kings gave us a foundation, an array of sounds we knew were likely to be in the Draconean text, with a good guess as to where in the text those sounds fell. Although incomplete, this partial syllabary gave us a tremendous advantage over our past knowledge.

Having a sense of Draconean pronunciation, however, does not get us much further. What use is it to have confidence that a given symbol sounds like “ka” when I do not know what any of the words containing “ka” mean? In order to progress further, linguists must try a different tactic.

The word “king” occurs eight times in that recitation of lineage. Suhail and his compatriots had analyzed the frequency with which different series of symbols occurred in the Draconean text, seeking out any grouping that occurred eight (and only eight) times. They found a great many, of course, the vast majority of which were coincidental: the fact that the combination “th” occurs eight times in this paragraph before the word “coincidental” is not a significant matter. (Anyone reading this memoir in translation will, I suppose, have to take me at my word that eight is the proper count.) But the linguists became confident that they had, through their statistical efforts, identified the Draconean word for “king.”

This is only the tip of the dragon’s nose, when it comes to the methods of linguistic decipherment, but I will not attempt to explain further; I would soon outpace my limited expertise, and the means by which they identified the inflection for plural nouns or other such arcana is not necessary to understand what follows. Suffice it to say that on that afternoon, we knew two things with moderate certainty: the proper pronunciation for roughly two-fifths of the Draconean syllabary, and a scattered handful of words we had tentatively reconstructed, not all of which we were capable of pronouncing. It was a good deal more than we once had; but it was a good deal less than the entirety of what we hoped for.

My husband was an excellent lecturer; he laid all these matters out with both speed and clarity (the latter a quality so often lacking among scholars), before embarking upon the main portion of his speech. “Ideally,” Suhail said, “we should only use direct evidence in carrying our work forward. Hypotheses are of limited use; with so little data available to us, it is easy to build an entire castle in the air, positing one speculation after another whose validity—or lack thereof—can be neither proved nor disproved. But in the absence of another Cataract Stone or other breakthrough, we have no choice but to hypothesize, and see what results.”

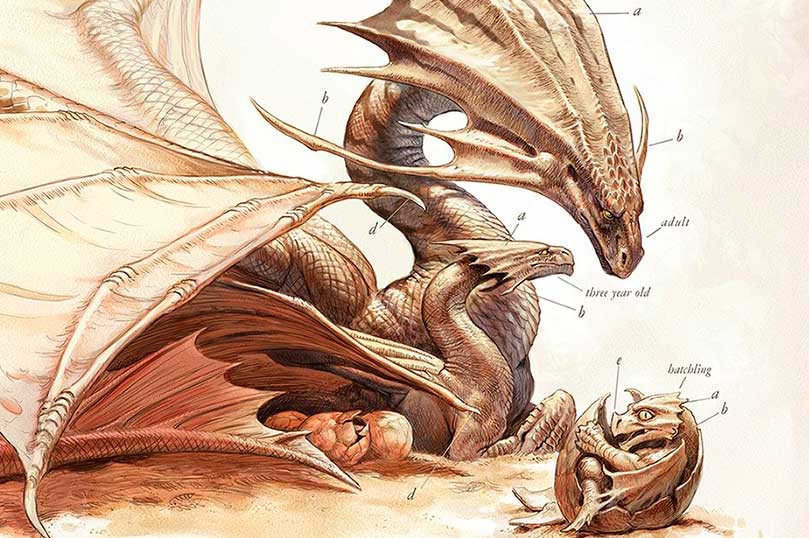

Miss Pantel, knowing her cue, moved to the next placard in the series. This showed the entire Draconean syllabary, laid out in something like a chart, with the characters whose pronunciations we knew coloured red. Scholars had made charts of the symbols many times before, in many different configurations; as Suhail had just noted, what facts we possessed could easily be poured into any number of speculative molds. This one, however, had more than mere guesswork to back it.

My husband’s resonant voice carried easily throughout the hall. “This is a modified version of the chart assembled by Shakur ibn Jibran, based on what we currently know regarding the pronunciation of established Draconean glyphs. He noted an underlying similarity between the symbols for ‘ka’ and ‘ki,’ and another similarity between ‘mi’ and ‘mu,’ and so forth. His hypothesis is that each initial consonant possesses its own template, which is modified in relatively predictable ways by a vowel marker. By grouping the symbols according to these templates and markers, we may theorize as to the pronunciation of glyphs not included in the proper names of the Cataract Stone.”

The process was not, of course, as straightforward as his description made it sound. Languages are rarely tidy; with the exception of the Kaegang script, designed a century ago for use in writing Jeosan, they show a distressing tendency to break their own rules. Although many linguists had accepted Shakur ibn Jibran’s general principle in arranging the glyphs, they argued over the specifics, and easily half a dozen variant charts had their own partisan supporters. Already there were murmurs in the hall, as gentlemen grumbled at not seeing their preferred arrangement on display.

Those murmurs would grow louder soon enough. For now, the chart gave us a place to begin—and Suhail’s own speculation depended upon his fellow countryman’s as his foundation. Miss Pantel revealed another placard, this one with lines of Draconean text printed upon it, interleaved with an alphabetic transcription.

My husband said, “If we take that speculation as provisionally true, then this selection—taken from later in the Cataract Stone text—would be pronounced as glossed here. But we have no way to test this theory: here there are no proper names to guide us. We will never know whether this is accurate … unless we speculate again.”

Taking up a long pointer, Suhail underlined a word in the first line. “Presuming for the moment that our chart is correct, these characters would be pronounced aris. One of the fundamental principles of historical linguistics is that languages change over time; tongues that are spoken today may have their roots in older forms, now extinct. The Thiessois word terre and the Murñe word tierra both derive from the Spureni terra, meaning ‘earth.’ So, too, may we hypothesize that aris gave rise to the Lashon ’eretz and the Akhian ’ard—also meaning ‘earth.’”

Had I been inclined to place a bet with myself, I would have won it in that moment, as the lecture hall burst into uproar.

Linguists had spun theories of this kind before, imagining the Draconean language to be ancestral to a wild variety of modern tongues, Lashon and Akhian not excepted. After all, the deserts of southern Anthiope were the most likely homeland of that civilization. But the common wisdom held that the Draconean lineage was linguistically extinct: the Draconeans had been a separate ethnic group, ruling over their subjects much as Scirland currently ruled over parts of Vidwatha, and with the downfall of their empire their language had vanished forever. It was almost literally an article of faith, as everyone from Scirling magisters to Bayitist priests and Amaneen prayer-leaders agreed that our modern peoples owed nothing to those ancient tyrants.

I had advised Suhail to stop after that statement, lest the clamour drown out his next words. He took my advice, but the pause lasted longer than either of us had anticipated. Finally he gave up on waiting for silence and went on, pitching his voice to be heard above the din of audience commentary. His point did not rest upon that single example: he believed he had found cognates for a number of words, methodically connecting them to examples in Akhian, Lashon, Seghar, and historically attested languages no longer spoken today. It was, as he had said to me, guesswork; all he could do was tentatively identify specific glosses from the Ngaru text, and then extrapolate into speculation on other Draconean inscriptions. One tablet from a site in Isnats, for example, seemed to be a kind of tax record, as he found probable words for “sheep,” “cow,” “grain,” and more.

Any one example could easily be shot down. Assembled together, however, they constituted a very reasonable theory—or so I thought. But I was not a linguist, and there were gentlemen in the audience that day who laid claim to that title. They were more than prepared to disagree with Suhail.

When I heard voices rising at the back of the hall, I assumed it was an argument over the substance of the lecture. The magister I mentioned before, ten rows ahead of me, had risen to his feet so as better to shout his disagreement at my husband; presumably the noise behind me was more of the same. When I turned to look, however, I saw a small knot of men at the door, facing one another rather than the stage.

Surely they would not begin an altercation over a matter of historical linguistics? But I have spent enough of my life among scholars to know that academic conflicts and fisticuffs are not always so far apart as one might expect. Rising from my seat, I went to see if I could defuse the situation before it reached that point.

But the argument at the door had nothing to do with Suhail’s lecture. From my seat, I had been unable to see the man at the center of the knot; now that I drew near, I caught a glimpse between the shoulders of the other men. He dressed in the manner of a northern Anthiopean and had his hair trimmed short, but a suit did nothing to change his features. The man was Yelangese.

Now, on the surface of it there was nothing so terribly strange about a Yelangese man attending a public lecture in Falchester. Ever since long-range maritime trade became a common feature of life, there have been sailors and other immigrants in Scirling ports, Yelangese not excepted. At the time of Suhail’s lecture, though, we were firmly in the grip of what the papers had dubbed our “aerial war” against Yelang, wherein our caeligers and theirs jockeyed for position all around the globe, and our respective military forces clashed in a series of minor skirmishes that kept threatening to break out into full-scale war. Men of that nation were not exactly welcome in Falchester, regardless of how long it had been since they called the empire home.

Furthermore, readers of my memoirs know that I had quarreled with the Yelangese on multiple occasions: when I was deported from Va Hing, when I stole one of their caeligers in the Keongan Islands, and when they made organized efforts to sabotage our work at Dar al-Tannaneen. This was public knowledge at the time, too—which meant that the gentlemen near the door, seeing a Yelangese man show up at my husband’s lecture, had leapt to some very hostile conclusions.

I kept my voice low, not wishing to draw any more attention than this incident already had. Fortunately, the magister who had stood up was still on his feet, along with another man who was attempting to shout over him. “Gentlemen,” I said, “I suggest we take this matter out into the lobby. We do not wish to disturb the lecture.”

There are benefits to having a famous reputation. The men recognized me, and were more inclined than they might otherwise have been to heed my suggestion—which was, of course, a thinly disguised order. One of them shouldered the door open, and we escaped into the relative quiet and privacy of the lobby.

“Now,” I said, once the door had swung shut behind us. “What appears to be the problem?”

“He’s the problem,” the tallest of the Scirlings said, jerking his chin at the foreigner. He topped the Yelangese man by more than a head, and was using his height to loom menacingly. “I don’t know what he thinks he’s about, coming here—”

“Have you tried asking him?”

A brief pause followed. “Well, yeah,” another man admitted. “He said he was here for the lecture.”

“Anybody can say that,” the tall man scoffed. “That doesn’t mean it’s true.”

“Nor does it mean it’s false,” I said. In truth, though, I suspected there was indeed more to the story. The Yelangese stranger, though doing his best to keep a bland expression, had clearly recognized me. Which was all well and good—as I have said, I was very recognizable—but something in his manner made me suspect I was his reason for coming to Caffrey Hall that day.

My tone was therefore sharp as I addressed the stranger. “What is your name?”

“Thu Phim-lat,” he said, in a heavily accented voice. “Lady Trent.”

So he would not attempt to pretend that he did not know me. Under the circumstances, none of us would have believed him anyway. “How long have you been in Scirland?”

“Three weeks.”

My heart stuttered in its beat. Perhaps you think it was a foolish reaction; I will not argue with you. But I had been on the receiving end of Yelangese trying to kill me, and could not forget that so easily. Had Thu Phim-lat been a longtime resident of Falchester, I might have persuaded myself that he was no threat. But if he had just arrived …

I decided to press the matter. “You may be here for the lecture, Mr. Thu, but I doubt that is your only purpose. Tell me what you hope to accomplish.”

His eyes darted from side to side, taking in the men watching us. They had arrayed themselves quite close, clearly ready to interpose their bodies if Mr. Thu made a single move toward me. “Oh, come now,” I said impatiently—as much to myself as to them. I did not like feeling afraid in my home city, and I liked even less feeling afraid when I had so little cause. “If he wished me any harm, there are far easier ways for him to achieve it than by walking into a public lecture hall.” He could have accosted me on the street, appearing out of the crowd before I even knew he was there. A cosh to the back of the head, a knife between the ribs … but that was foolishness. Yelang had only troubled me when I troubled them, by investigating dragons in their country or attempting to breed my own for the Royal Army. There was no reason for them to assassinate me at home, unless I had made a much more personal enemy than I knew. And doing so would only make them look dreadful in the court of public opinion.

The Scirling men looked unconvinced, but I had persuaded myself, and reassured Mr. Thu enough that he answered me. “I wished to meet you,” he said, speaking very slowly. I realized later that this was because his grasp of the Scirling language was far from perfect, and he wanted to make certain he committed no errors of grammar or word choice that might cause his point to be taken awry. “I have news of a thing I think you would like to hear.”

“News may be sent by letter,” I said. “Or you could present yourself at my townhouse—its location is hardly a secret. Why come to a public lecture?”

“If I came to your home, would I be let in the door?” he asked. “Would my letter be read?”

“Yes, or else my servants would have a great deal to answer for. I do not pay them to make such decisions on my behalf.”

“Ah,” Mr. Thu said once he had taken in these words. “But how would you know?”

I dismissed this with a wave of my hand. “Clearly you have not been rebuffed in such fashion, or you would have said as much already. Let us not waste time with hypotheticals. What tidings are you so eager to convey?”

At many points in my life I have been on Mr. Thu’s end of such a conversation, stumbling along in a language of which I have only a rudimentary command. My rapid speech and elevated diction had lost him. “Your news,” I said, when I saw he did not understand. “You have found me; say what you came to say.”

He glanced again at the men so energetically looming at him. “A dragon,” he said at last. “The body of a dragon. Not like any kind I know. I think not like any kind alive.”

My heart stuttered again, this time with excitement instead of irrational fear. Not like any kind alive. An extinct breed … I had scoured the world, corresponding with scholars from a dozen countries and more, trying to find evidence of the dragons created by the Draconeans so many thousands of years ago. Could it be this man had found what I sought?

It was unlikely. Even if he had only discovered evidence of some other extinct strain, though, he had my keen interest. “Where?”

“In the mountains,” Mr. Thu said. “You will see.”

Copyright © 2017 by Bryn Neuenschwander

Red Right Hand by Levi Black

Red Right Hand by Levi Black Firebrand by A. J. Hartley

Firebrand by A. J. Hartley Skullsworn by Brian Staveley

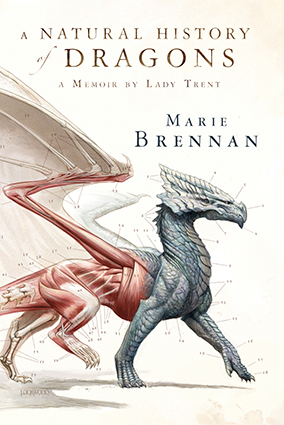

Skullsworn by Brian Staveley Within the Sanctuary of Wings by Marie Brennan

Within the Sanctuary of Wings by Marie Brennan The Guns Above by Robyn Bennis

The Guns Above by Robyn Bennis Roar by Cora Carmack

Roar by Cora Carmack Updraft by Fran Wilde

Updraft by Fran Wilde Everfair by Nisi Shawl

Everfair by Nisi Shawl The Queen of Swords by R. S. Belcher

The Queen of Swords by R. S. Belcher