Where would we be without our books? is a tough question, and not just because we work for Tor. Before we were workers in publishing, we were people who enjoyed books, and we’re still that. We always will be.

In spirit of the season, here’s some of the books that Tor staff are thankful for this year.

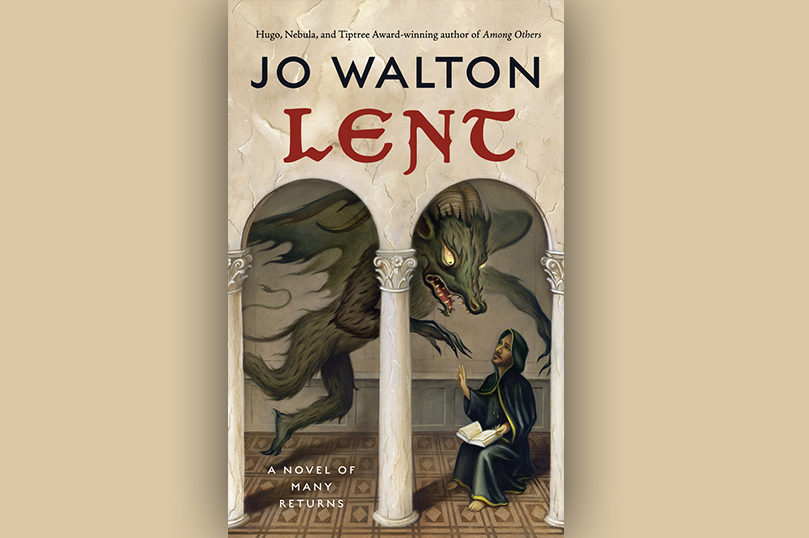

opens in a new window opens in a new windowOne for My Enemy by Olivie Blake

opens in a new windowOne for My Enemy by Olivie Blake

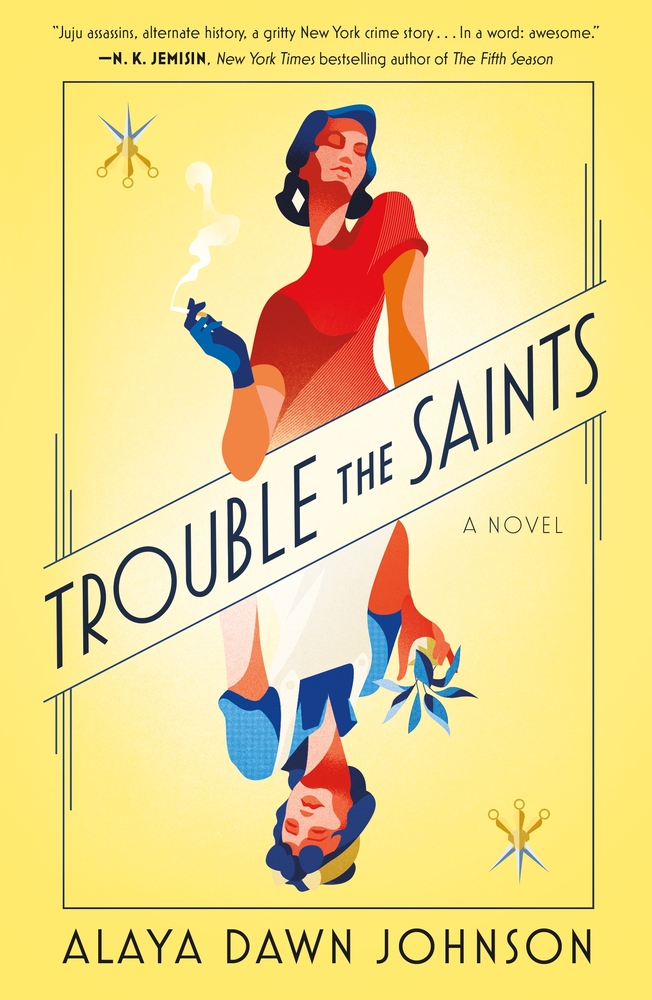

Increasingly, I am becoming convinced of the singular importance of vibes, and its verb form, vibing. Vibing is a modification of everything else you do—it’s existing with intention and style. So I’m going to talk about now, a book with impeccable vibes, where rival witch dynasties compete for each other’s affections and dominance over Manhattan’s magical, criminal underworld. It’s One for My Enemy, and it vibes severely.

a cat, Assistant Marketing Manager

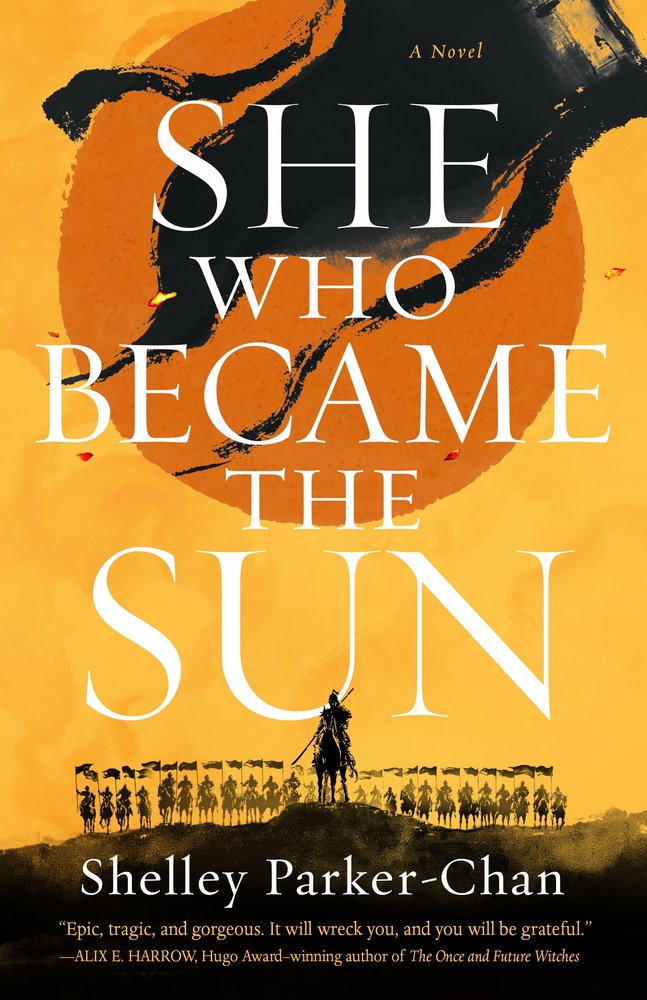

opens in a new window opens in a new windowHe Who Drowned the World by Shelley Parker-Chan

opens in a new windowHe Who Drowned the World by Shelley Parker-Chan

Yvonne Ye, Ad/Promo Coordinator

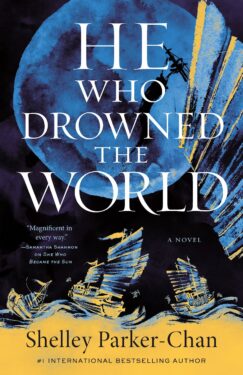

opens in a new window opens in a new windowLent by Jo Walton

opens in a new windowLent by Jo Walton

This year I am grateful for a book that kept me up way past my bedtime. Lent is full of twists, tormented monks, and demons, demons, demons. Read this fiendishly clever, fantastical take on historical fiction at your own peril and definitely not if you need to wake up early the next morning.

Merlin Hoye, Marketing Assistant

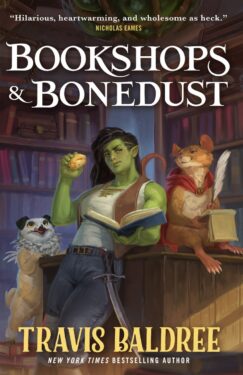

opens in a new window opens in a new windowBookshops & Bonedust by Travis Baldree

opens in a new windowBookshops & Bonedust by Travis Baldree

This is the year of Travis Baldree. Legends & Lattes was my favorite book of 2022 and he knocked it out of the park once again with Bookshops & Bonedust. It was another perfect, cozy, sapphic fantasy novel with just an edge of bittersweet longing that had me clutching the book to my heart. I’m so grateful for the comfort and joy this book provided me with this year and I can’t wait to re-read this book again. And again. And again.

Rachel Taylor, Senior Marketing Manager

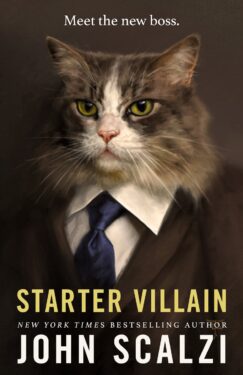

opens in a new windowStarter Villain opens in a new window by John Scalzi

by John Scalzi

Oh, to be able to read this book all over again with fresh eyes. Starter Villain by John Scalzi is such a fun, fast-paced romp that asks the very important, age-old question: what if my cats could talk (and also I was rich)? The cats would tell you to read this book about inheriting evil empires, unionizing dolphins, many (many) assassins, and one divorced substitute teacher who just wants to be able to keep his house.

Lizzy Hosty, Publishing Strategy Assistant

What books are you thankful for? Let us know in the comments!

The Calculating Stars

The Calculating Stars Lent

Lent