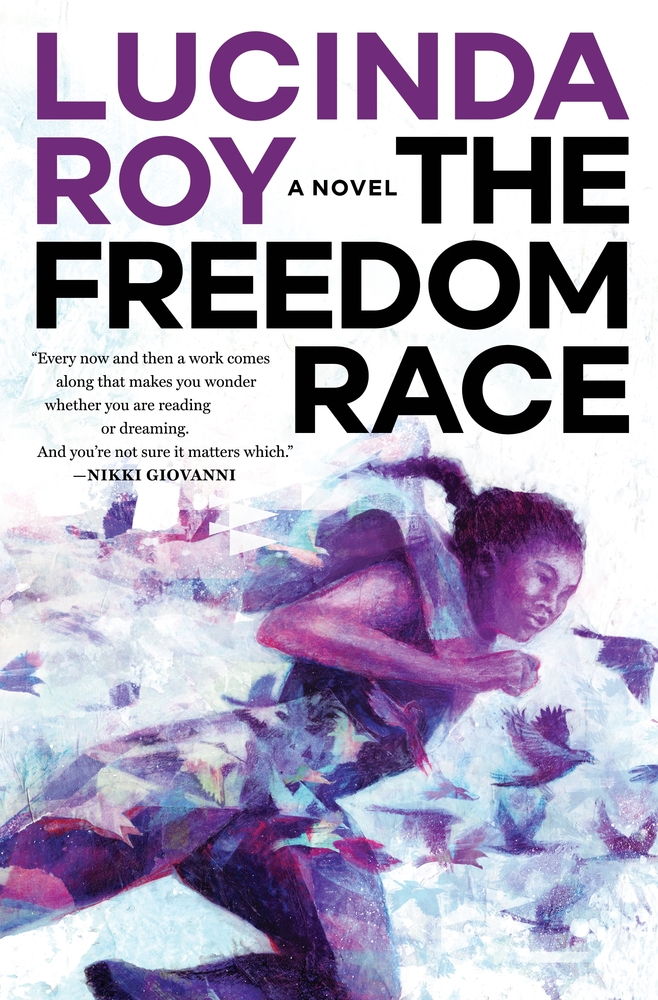

Every fantasy world needs a map, right? But what happens when the map needs to come from the hands of the characters you’ve written? Lucinda Roy, author of upcoming speculative fiction novel opens in a new windowThe Freedom Race, discusses her journey to drawing the maps in her book and how her characters helped shape the art she created. Check out the article PLUS our exclusive map reveal below!

Every fantasy world needs a map, right? But what happens when the map needs to come from the hands of the characters you’ve written? Lucinda Roy, author of upcoming speculative fiction novel opens in a new windowThe Freedom Race, discusses her journey to drawing the maps in her book and how her characters helped shape the art she created. Check out the article PLUS our exclusive map reveal below!

By Lucinda Roy

I was writing The Freedom Race when it struck me in the head like the muck thrown at poor Cersei Lannister during the “Shame, shame shame!” scene in HBO’s Game of Thrones: I needed a map!

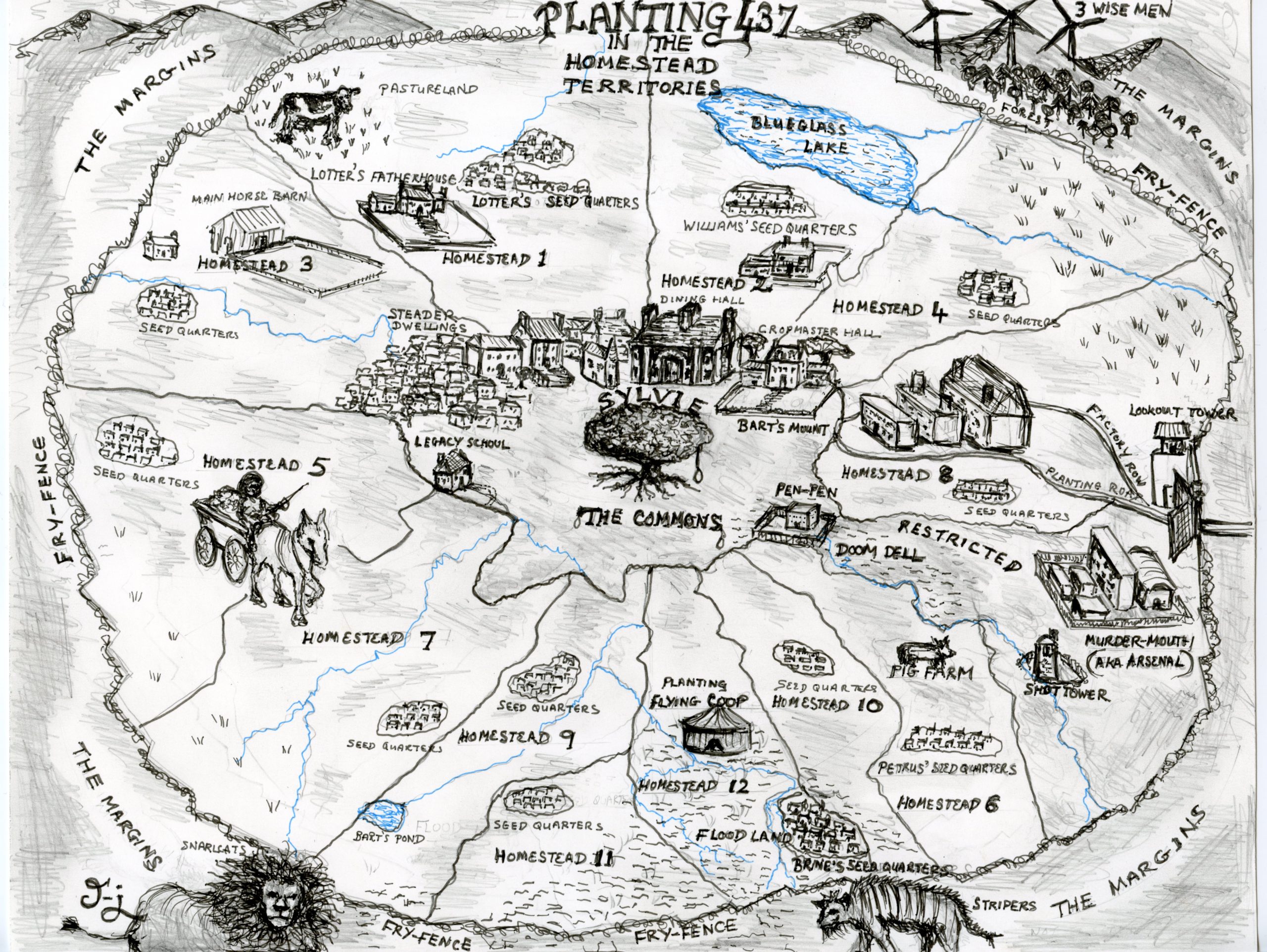

Not only did I need a map, I needed a persona map—a map that could feasibly have been drawn by Ji-ji, the main character in the book. Her map doesn’t simply introduce the world to readers, it actually appears inside the narrative and helps catalyze the action.

When I realized I’d assigned myself the task of drawing Ji-ji’s map of the planting, the British/American half of me was gobsmacked—appalled I hadn’t realized from the get-go maps would be a necessity. The Jamaican half of me was laid back about it. I mean, how hard could it be to draw a map or two, man? After all, I wasn’t a virgin when it came to drawing. I’d even sold some of my original oil paintings in the past, and others had been featured on the covers of my poetry collections. A map would be a breeze, right? Wrong.

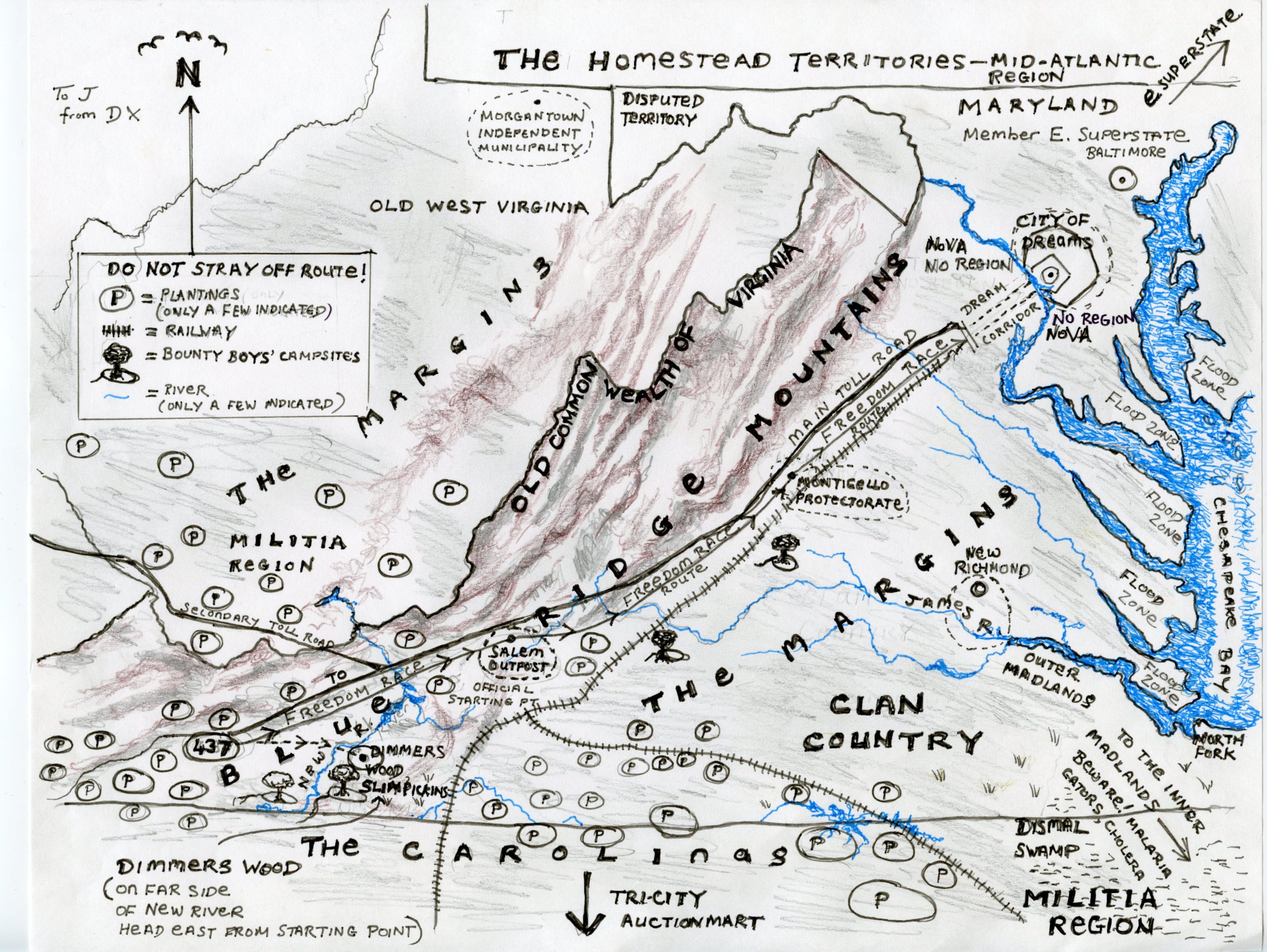

I soon realized there wasn’t one but two maps I needed to draw for this first volume in The Dreambird Chronicles trilogy. And there was another problem: the world in The Freedom Race isn’t typical sci-fi or fantasy. Instead, it balances on the rim of realism and magical realism. Its angles are satirical and its landscapes feature a bone-chilling nostalgia for the plantations of the past.

I decided to trust my instincts—or rather my characters’ instincts—and see what happened. The first map is drawn by Jellybean “Ji-ji” Lottermule (her signature is there on the bottom left of the map); the second is drawn by an elderly Black wizard known to everyone as Uncle Dreg.

The tone of Ji-ji’s map is rebellious. “Imaging a planting” is a cardinal offense in the Homestead Territories, evidence of sedition. Yet Ji-ji—a biracial Muleseed classified as a botanical—has dared to depict the place where she was raised in captivity. Drawing this map is one of the most dangerous things she’s ever done. If her father-man discovers it, the punishment will be severe.

Yet Ji-ji dares to draw the world she knows because, for enslaved people, there is nothing more powerful than testimony. Speech testimony, map testimony, video testimony—all these tools are used by oppressed people to empower themselves.

Ji-ji’s map becomes an affirmation of who she is as a sentient human being. She’s seen what is really going on in the segregated Homestead Territories. She dares to record it because silence is invariably a form of complicity.

The second map is a gift to Ji-ji from Uncle Dreg, a Toteppi wizard, which is why he signs it “To J from D,” just above the box containing the key, near the three blackbirds. Dreg’s map depicts the Old Commonwealth of Virginia in the Southeastern Homestead Territories, a place that thrived during our time, the Age of Plenty, but which, in the future, is a place of grave jeopardy for people of color.

The tone of Uncle Dreg’s map is one of warning. There are areas to avoid: The Margins, Clan Country, and Militia Regions, and a path to follow up to Dream Corridor and the City of Dreams. This is the race route Ji-ji must take if she’s selected to compete in the Freedom Race. There are clues in the map about what may transpire in the future because Dreg is reputed to have the ability to see through the Window-of-What’s-to-Come.

People who read speculative fiction routinely do something daring. We enter the unknown, a world that exists almost entirely in the author’s head. We trust this stranger to guide us. Maps take hold of the often-chaotic maze of a writer’s imagination and make it orderly and accessible. Amazing to think that a few lines consigned to paper can endow imagined worlds with realness.

The maps in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, and Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, to name just a few, function as tantalizing entry points into invented worlds. The best maps whisper: “This strange world is worth believing in. Come inside and see for yourself.”

Having drawn the maps for The Freedom Race, I’ve concluded that authors of speculative fiction who draw their own maps should get extra points. (I feel the same way about undersized ballers, who should be entitled to double points when they slam-dunk because they have further to go to reach the rim.)

Drawing a map is much harder than it looks, especially for a charmingly neurotic writer who’s made a circuitous journey to speculative fiction via poetry, mainstream literary fiction, and memoir. (“Charmingly” being my adverbial attempt to downplay my idiosyncrasies.) The further I got into the story, the more I realized that the characters themselves—particularly Ji-ji, whose point of view drives the first novel in the series—use them as ways to interpret the world they inhabit.

Maps reveal what we value in ways we don’t always recognize. Look at how maps of the world with Europe at the “center” of a flattened, totally unrealistic, and arbitrary depiction of the globe reveal so much about the power dynamic. Which countries are in the center? Which countries grab the most room for themselves? Which are made to look less impressive, more marginal?

The images we carry around in our heads shape who we are, and those who lay claim to the most memorable imagery often win. Instinctively, Ji-ji knows this, which is why she’s willing to risk her life to draw a map of the planting. The map says, “Ji-ji was here.” The map says she witnessed this travesty.

As I write this, I realize there is another reason why drawing the maps made me nervous: the Afro-futuristic world I was depicting intersects closely with today’s world, where the insidiousness and tenacity of racism is again on display. People of color and their stalwart allies are grieving. At a time of racial upheaval, these characters (for it was they who guided me) drew race into these maps. The warnings on Uncle Dreg’s map reverberate throughout the series and throughout today’s world.

Maps make us believe order is attainable. But orderliness can itself be the perpetrator of evil. It can fool us into believing all is well, persuade us that the status quo is beneficial, and that peace at all costs is the preferred way to live. It’s how the secessionist, segregationist steaders in the world of The Freedom Race persuaded other parts of the Union, still reeling from a Civil War Sequel, climate change, and a metaflu pandemic, that peace was preferable to chaos.

But Ji-ji and Uncle Dreg know that peace without justice is a curse. These maps are their attempt to show us why. The orderliness of the wagon-wheel layout of Planting 437 in Ji-ji’s map is what makes it so sinister.

People don’t rule the world—ideas do. And what is a map if not an impossibly large idea projected onto a small page or screen? As we embark on what I hope will be a worthwhile journey for readers of The Freedom Race, the maps drawn by the characters tell me where to go. My hope is that they will also speak to you.

Novelist, poet, and memoirist Lucinda Roy is the author of the speculative novel The Freedom Race and three collections of poetry, including Fabric: Poems. Among her awards are the Eighth Mountain Prize for Poetry, and the Baxter Hathaway Prize for her long slave narrative poem “Needlework,” and a state-wide faculty recognition award. The Freedom Race is available anywhere books are sold on July 13, 2021.

Pre-order The Freedom Race Here:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window