opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

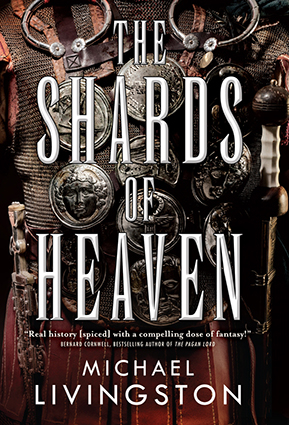

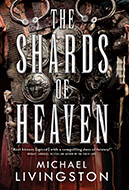

opens in a new window Welcome back to opens in a new windowFantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an excerpt from opens in a new windowThe Shards of Heaven by Michael Livingston, a historical fantasy set at the birth of the Roman Empire. Civil war rages in Rome, but it is a secret war for the lost treasures of the gods that will shape the first century BC. opens in a new windowThe Realms of God, the conclusion of the trilogy, will be available November 7th.

Welcome back to opens in a new windowFantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an excerpt from opens in a new windowThe Shards of Heaven by Michael Livingston, a historical fantasy set at the birth of the Roman Empire. Civil war rages in Rome, but it is a secret war for the lost treasures of the gods that will shape the first century BC. opens in a new windowThe Realms of God, the conclusion of the trilogy, will be available November 7th.

Julius Caesar is dead, assassinated on the senate floor, and the glory that is Rome has been torn in two. Octavian, Caesar’s ambitious great-nephew and adopted son, vies with Marc Antony and Cleopatra for control of Caesar’s legacy. As civil war rages from Rome to Alexandria, and vast armies and navies battle for supremacy, a secret conflict may shape the course of history.

Juba, Numidian prince and adopted brother of Octavian, has embarked on a ruthless quest for the Shards of Heaven, lost treasures said to possess the very power of the gods—or the one God. Driven by vengeance, Juba has already attained the fabled Trident of Poseidon, which may also be the staff once wielded by Moses. Now he will stop at nothing to obtain the other Shards, even if it means burning the entire world to the ground.

Caught up in these cataclysmic events, and the hunt for the Shards, are a pair of exiled Roman legionnaires, a Greek librarian of uncertain loyalties, assassins, spies, slaves…and the ten-year-old daughter of Cleopatra herself.

PROLOGUE

THE BOY WHO WOULD RULE THE WORLD

OUTSKIRTS OF ROME, 44 BCE

Hidden amid the shadows outside Caesar’s marble-columned villa, the assassin Valerius gazed back across the valley to Rome. Coiled around and upon her seven hills, the Eternal City often seemed like a living thing, her old streets pulsing with life. But now, on this fading day, the city was quiet and still. Her ancient stones, alight with the reds of a setting sun, appeared to be weeping blood. Valerius saw in the image a sign of favor.

The dictator was dead. And the gods approved.

Caesar’s blood, he did not doubt, still stained the tiled floor of the east Forum. Pushing his way through the astonished throngs of onlookers after the deed, Valerius had seen for himself the mangled corpse, wrapped in the tattered remains of Caesar’s purple robes, and in his mind’s eye the thick crimson pooled there was the perfect mirror to the strong light before him now.

Valerius’ knife, which he absently turned over in his hands as he watched Rome’s red walls slowly fade to gray, had not been among those that drank of Caesar, and he thought it a pity. The rich senators who’d done the killing were emotional men, ineffective at murder. Even with so many cuts to his body, Caesar had taken some minutes to die. The sprawled trail of blood on the tiles had told the tale. And though Valerius felt no particular love for the would-be emperor, he nevertheless thought it shameful that any man should shake out his last breaths under the eyes of dishonorable men.

Shameful, but little for it: Valerius was under no employ for that killing, and the man who had arranged to hire him only hours afterward would never have wished Caesar dead. Octavian still called the dictator “Uncle Julius” despite all the titles and glories that Caesar had won over his great-nephew’s nineteen years. In the streets some citizens were even saying that Caesar had adopted the young man, that Octavian might well be his heir. That was certainly what Octavian seemed to think.

Valerius spit into the vines that gathered about the foot of the villa wall at his back. He knew little of politics himself: he cared for them only insofar as they affected his own movements. Heir or not, adopted son or not, Octavian was his employer now. So Valerius cared only that his employer’s beloved uncle was dead and that he had been hired to see that Caesarion, the son of Caesar and Cleopatra, the only blood child of the now-dead dictator, would follow his father to the grave.

As he stopped to think about it, it seemed for a moment odd to Valerius that Octavian should wish the child of Julius such harm. The assassin had never seen the boy, but it was said that, aside from his slightly darker tone of skin and more delicate Egyptian features, Caesarion had every part the striking resemblance to his father. Then again, as heir of Egypt and the only surviving child of Julius Caesar himself, Caesarion did stand in line to inherit the world. And if Octavian thought himself rightful heir to at least part of that world … well, no price would be too high to see the boy dead.

Not that it really mattered. Octavian’s reasons were immaterial in the end. Not like the hundred weight of gold Valerius had been promised for the killing. That was material indeed.

Up the hard-packed dirt road from the bridge over the Tiber came the sound of hooves, a punishing gallop of men in fury. Valerius took a deep breath to clear his mind of reasons in order to focus on the simple facts of the task at hand: to get into the villa and end the child’s life. With practiced speed he pocketed his blade, fearful of any glint it might give off despite the deep shadows and brush in which he crouched.

The staff emblem rattling above the lead rider showed the markings of Caesar’s famed Sixth Legion, and even before they were close enough for the assassin to see the details of the faces of the riders themselves, he knew the man at their center to be Mark Antony: the general was broad-shouldered and handsome in his signet robes, with thick curls of red hair bouncing at every downbeat, and he exuded arrogance and assumptive power with every movement. Even the strong and impassioned way he drove his steed, completely heedless of consequence to the beast, seemed emblematic of the man. If the citizens of Rome knew but one thing about Antony it was that he was full of fire, his eyes never alight on anything but his goal. He’d been Julius Caesar’s finest general, perhaps his best friend, and for some reason—Valerius couldn’t fathom why—his life had been spared by the conspiratorial senators.

Valerius slowly and methodically stretched some of his tense muscles, grateful for Antony’s appearance. He’d counted on an emissary coming to call on the distraught queen of Egypt, but none could be more ideal than Antony. Chaos followed the man like the wake of a passing ship, and his arrival would be sure to send the household into even greater confusion than that which it already labored under, making it far easier for the assassin to complete his work.

Tucked behind the drapes of a momentarily calm foyer, his lungs moving shallow and silent, Valerius listened to the sounds of the villa: servants’ feet rushing between rooms, pots and dishes being moved about in the kitchens, the muted sobs of a woman crying, and, very close, the quiet breathing of someone waiting in a nearby doorway. A male someone, by the sound of the breathing. Octavian’s contact, he hoped.

Valerius lifted himself to the balls of his feet, floating out from his hiding place. A long wide swath of torchlight cut across the darkened floor of the foyer, spilling out from the doorway where the man waited, effectively blinding whoever it was to anything moving in the shadows. The assassin glided carefully around the periphery of the room until he stood beside the doorway. Then he took a small rock from his pocket and tossed it lightly out into the open.

The man in the doorway started at the sound of the pebble clattering across the floor, and he took a few hesitant steps into the open. “Hello?” he whispered. His voice cracked. “Is someone—”

The man’s quaking voice was frozen by the dull back of the assassin’s blade against his throat. Valerius guided him with it, pulling him into the darkness away from the doorway. “Yes,” the assassin breathed in his ear. “Someone is here.”

“I’m … I’m…”

“That’s not the code word,” Valerius said, pressing the steel against his skin.

The man’s body shook in fright, and his neck spasmed before he finally controlled himself enough to remember the arranged sign. “Tiber,” he croaked. “Tiber.”

Immediately Valerius released and spun Octavian’s contact around to get a good look at him. The man was younger than he’d anticipated, perhaps not even twenty. He had the smooth skin of someone unaccustomed to manual labor and the outdoors, and the tone of his complexion showed he was not Italian stock, though it was also more olive than the deeper tan of Cleopatra and her Egyptian court. A Greek, probably. Or a Cretan.

“I’m Didymus,” the man said. “I didn’t—”

“Where’s the boy?”

“The boy?”

“Little Caesar,” Valerius hissed.

A new fear crossed Didymus’ face. “Varro said you wanted Cleo—”

The assassin’s voice turned low and dangerous. “Octavian will pay you, yes?”

Didymus nodded, his expression numb.

“Pay you well?”

“Yes,” Didymus managed.

“Then don’t waste my time,” Valerius whispered, raising the knife for emphasis. “Where?”

Didymus swallowed carefully, his eyes dark. After a moment he lifted his arm in the direction of the lighted, open doorway. “Through my room, left beyond the curtains. Two rooms down there. Caesarion’s is the first.”

“Guards?”

“One inside. Abeden. An Alexandrian.”

“And the Egyptian whore?” Octavian hadn’t ordered it, but Valerius was certain there’d be a substantial bonus if both mother and child died tonight. No one in Rome had approved of Caesar’s dalliance with the foreign queen.

The fear in Didymus’ face was replaced with something more focused and harsh. Something more like the jealousy of a jilted lover. “Her room’s beside his. You’ll know it for the moaning.”

Valerius nodded, lowered his blade, and padded into Didymus’ room. The furnishings were simple enough, but the walls were lined with tables, each stacked tall with scrolls in various states of binding. The traitor was a tutor, he surmised. Probably the boy’s. It would explain his hesitation.

The household was still busy at the front of the villa. He could hear Antony bellowing commands, sending the servants scurrying to tend to his horse and to bring wine for his own dust-dried throat. Soon, the assassin imagined, Antony would dispatch one of his legionnaires to fetch Cleopatra.

The assassin doubled his speed as he made his way through the curtained rooms and hallways, keeping to the shadows as much as he could, closing in on the sound of the sobbing woman he now knew for certain to be the queen of Egypt. He encountered no one before he reached Caesarion’s door, where he paused to listen for sounds of movement within.

Valerius smiled once more. If the bloodred light of the sunset and the ease of his passage were not surety enough of the gods’ blessing on his task, the few noises inside the room would have passed all doubt from his mind. The boy was playing quietly, and from the sound of it Didymus was right about the single guard.

The assassin knocked lightly on the door, then right-palmed his knife. The door cracked, filled with an Egyptian face.

Valerius bowed slightly, kept his voice low and his posture submissive, like a servant’s. “The queen requests your presence, Abeden. There’s talk of moving the boy.” He stood to one side, so as to let the guard pass into the hallway. “I’m instructed to stand at the door in your absence.”

The guard glanced back at the room, then stepped out into the hall, pulling the door shut behind him. He turned in the direction of Cleopatra’s room. As he did so, Valerius came forward at his back, knife moving in a rapid strike up and into the center of his throat, puncturing his voice box. Then, in a smooth and practiced motion, he pulled the blade back and up and out, severing the vital arteries on the right side of the guard’s neck even as his free hand gripped the man’s weapon arm and used it as a lever to turn his body and send the bright red spray against the wall, out of sight of the boy’s doorway. He pinned the man there for a moment as he shook and gurgled, then he stabbed him once more, this time in the left center of his chest.

The guard sagged, only twitching now, and Valerius let him down to the floor quietly before checking his own body for blood. As he expected, only his knife hand had met with the stain, and this he was quick to wipe clean on the dead guard’s tunic. Pocketing the weapon, Valerius dragged the man into a slumped position with his back against the wall. From a distance, he’d look like he was sleeping. Valerius would have liked to hide the body completely, but then he’d need to clean up the blood. And, besides, he planned to be finished with his tasks and fleeing through one window or another in a matter of minutes.

Shaking out his own shoulders and straightening his back, the assassin approached the door, knocked once, opened it, and stepped inside.

The room was modest but not small: perhaps fifteen feet square, with only a single wood-shuttered and curtained window above a well-cushioned bed. Caesarion, the boy who might inherit the world, the three-year-old child he had been sent to kill, was kneeling in the middle of the floor, surrounded by a small toy army: chariots, horses, and warriors. The assassin hadn’t been sure what to expect, but he was surprised nonetheless to find the little prince dressed in a simple belted Roman tunic and thong sandals, no different than any three-year-old one might find in a market in the city. Even more surprising, though, was how much he resembled his father: he had dark hair cut round and flat against a strong brow, the prominent nose of the Julians, and, when Caesarion looked up, his dead father’s piercing dark brown eyes.

“I’m one of Antony’s men,” Valerius said, smiling as he did to all children. “We’re going to go see your father.” Behind his back the assassin carefully pushed the door’s bolt into position, locking the room.

Caesarion nodded, and his voice was quiet and even. “See Father,” the little boy said.

Valerius took a step forward in the room, nodding solemnly. “That’s right. I’m sorry for your loss, my lord.”

Little Caesar blinked, then looked down to the wooden figures gathered around him on the floor. His hands moved a Roman chariot forward, knocked over an Egyptian warrior.

Two steps closer. “Your father was a great man. He often won victory over unspeakable odds.”

The boy nodded more strongly this time. He picked up the fallen Egyptian warrior, stood it on its feet and then stared, his face blank, at the pieces before him. “I know,” he said.

Valerius took another step to stand behind Caesarion, his hand moving stealthily to his pocket to retrieve the warm knife. Slowly, deliberately, he bent at the knees, crouching behind the child and gauging his neck. “I am sorry,” he said, and he started to reach forward.

An alarmed shout rang out in the hallway, the hard voice of a man. It froze the assassin’s hand as his head turned instinctively toward the locked door and his mind recalled the possible escape routes he’d mapped out beyond the window.

Caesar’s son, his own head turning at the shout, saw the assassin’s weapon and pushed himself away, scattering toys. He backed into the wall, brandished a wooden play knife in his shaky hands.

Valerius, still crouched with his own knife in hand, was mildly surprised when he looked back to the boy. “You’re fast, little one.”

“Don’t hurt me,” Caesarion whimpered.

The assassin stood. In another context, with a man before him instead of a boy, he would have smiled. But not here. No smiles, but no lies either. “I have to.”

Caesarion shook his head, swallowed hard. His eyes were dampening, but he didn’t cry.

There were answering shouts from within the villa. A sudden crash jolted the locked door, but it held. Valerius found it ironic that Caesar’s slaves had kept the house in such good working order that he’d be able to murder the man’s son in peace. By the time they breached the door he’d be out the window and on the run, the child dead. Alas that he’d not get the chance at the queen, too. The bonus would have been nice.

“No,” Caesarion stammered. “Please … no.”

Valerius settled his knees a little for balance, eyes taking stock of the child’s fake knife. The boy couldn’t do him any real harm with it, but the assassin didn’t intend to take home even a scratch from this assignment.

There was a crash from Cleopatra’s room next door, like the toppling of a great table, and the queen’s lament turned to sudden screaming. Not seconds later there was another crash, and Cleopatra’s voice grew even louder.

Caesarion’s wooden weapon trembled more violently in response to his mother’s terrified wails, and Valerius took a single step backward, giving himself room for a blade-dodging feint as he charged. He took a breath. Tensed.

Before Valerius could engage, heavy, running footfalls sounded beyond the shuttered window, and he had chance enough only to turn in the direction of the sounds before the wood slats separating the room from the growing night exploded inward as a massive legionnaire came through, tumbling over the bed and into his side.

The two men flailed to the floor together, grunting as splintered wood fell like rain in the little room. Valerius hit the ground first, but he was able to kick his lower body up in continuation of the legionnaire’s momentum, sending the far bigger man hurtling against the barred door. The assassin then rolled quickly, recovering his balance even as the dazed legionnaire scrambled to get his feet under him and began pawing for the gladius at his side.

Valerius came forward at him, knife ready in his grip, but before he could strike he screamed and buckled to one knee as Caesarion jammed his little wooden blade into the soft flesh at the back of his right leg. The assassin swung his arm back at the boy instinctively, catching him above the eye with the butt of his knife, sending him sprawling.

Gritting his teeth against the pain, Valerius turned back around in time to see the big legionnaire draw an arm back and forward, pushing a gladius into his belly, just below his rib cage. Gasping against the cold steel in his gut, the assassin still tried to swing his knife, but the legionnaire held fast to his sword with strong hands, and his thick arms flexed as he twisted it in his grip, scratching the blade into bone. Valerius groaned, strained, then dropped his weapon and sank against the killing stroke, watching, helpless and gasping in broken breaths, as the legionnaire stood, wincing from wounds of his own, and pushed forward until the assassin collapsed to his back.

For a few short gasps, Valerius could see nothing but the ceiling, and then the legionnaire returned into his view. The assassin stared in paralyzed shock as the bigger man painfully lifted a foot and planted it on his chest. Valerius heard a crunch that he strangely could not feel as the foot pressed down and the gladius was pulled free with a jerk of the legionnaire’s burly arms. Thick warmth washed over the assassin’s chest. Then the legionnaire was gone, limping over him and out of view.

“Caesarion,” Valerius heard the man say somewhere over his head. “You hurt?”

The child was crying now, and he heard the flex of leather and a grunt.

“There, there,” the legionnaire was saying. “All’s well, my boy. All’s well. You’re a brave lad.”

Valerius was having a hard time focusing now, but he saw the legionnaire come back into view. With an effort, Valerius turned his head to follow the man as he made his way toward the heavy door, holding the sobbing boy in one massive arm. Someone was pounding on the door—the assassin absently wondered how long that had been going on—and the legionnaire shifted the boy to his hip so he could unbolt it.

The door swung open to a crowded hall. There was a second legionnaire, smaller than the first, who must have been doing the pounding. Mark Antony was beside him, holding back a weeping, panic-stricken Cleopatra. And among the faces gathered behind them he saw Didymus, his Greek complexion gone pale with terror.

“Caesarion!” Cleopatra shouted, rushing forward to take the boy from the bigger legionnaire’s arms. By the gods, Valerius suddenly thought, she truly was beautiful. He’d heard talk of the queen’s beauty, and certainly from afar she had been remarkable enough for him to half-believe the talk that she was part-goddess herself, but seeing her up close he saw the honest truth: she was a woman of flesh and blood, a mother with fears and hopes. And also perhaps the most beautiful creature he’d ever seen.

The smaller legionnaire came forward, too, offering a shoulder to his injured comrade after he handed over the boy, but Antony pushed past them all to kneel before Valerius, filling his fading world with a flushed face and the scents of stale wine. “Who hired you?” the general demanded. His thick fingers rooted in the assassin’s tunic, causing the room to shift and bringing Antony’s face even closer. “Who let you in?”

Valerius looked to the Greek tutor, but when he tried to speak it came out as a wet cough. He felt an odd satisfaction to see flecks of red appear on Antony’s face. He tried to smile but wasn’t sure if the muscles of his face obeyed his mind’s command.

“Bah!” Antony said, releasing his grip. The assassin’s world unfocused, shook, then came back into clarity. He saw that Antony was standing now, surveying the room. “How’d you get to the window so quickly, Pullo?”

“Broke through the room next door, sir.” The battered legionnaire flicked his eyes to Cleopatra in her shift, and he bowed slightly. “Apologies, my lady.”

Cleopatra, looking up from stroking her boy’s head, seemed to have gathered control of herself. “No apologies, legionnaire,” she replied. “I owe you thanks.”

Valerius was aware of their voices receding, as if they were moving farther and farther away. It occurred to him that he was dying, a sudden, strange, and fearful thought. He felt his mind bucking and straining against the realization, clamoring to fight on, but his body did little more than tremble in an awkward breath. Even as that part of his mind screamed, another part of him observed his life passing with disinterest. He’d seen this kind of death before, where the blade cut the spine. Less common than the quivering horrors. Strange to experience it now.

“This is the second time I find myself in your debt, Titus Pullo,” Cleopatra was saying. Her eyes moved to take in the smaller legionnaire, on whose shoulder the big man now leaned. “And you, Lucius Vorenus.”

Through a growing fog of shadow the assassin watched as Antony looked to the two men for explanation. Pullo seemed to blush, and Vorenus in turn gave a shy smile before he spoke: “We brought the lady back to Alexandria before the siege, sir. Before she met Caesar. Was nothing.”

“I see,” Antony said gruffly. The room was almost gone now, and the general’s words were only a distant whisper as he advised the queen to return to Alexandria.

But Valerius was no longer listening. He was thinking instead of the faces of the dead, of the many shades that would greet him upon the other side. He thought of their anger, of their unslakable thirst for vengeance.

And then the voices in the room faded at last into a still silence, and Valerius saw light—clean, white light—before his eyes. He heard a gentle wind, the sound of water upon a sand-lined shore. The sun shone. Children sang. All times became one time. Valerius reached for his mother’s hand. He sat crying in an empty room. He lived. He died. He stood before the throne. And then darkness, an impenetrable and unquenchable black, rose up like a wave and overwhelmed all.

1

A WEAPON OF MANY GODS

NUMIDIA, 32 BCE

Standing at the craggy edge of a ridge that stabbed out into the stormy Mediterranean like a finger pointing north out of Africa—toward Europe, toward Rome—Juba frowned. The last thing the sixteen-year-old wanted to do was to resort to torture.

Sure, he’d read enough about the dark arts of physical pain to be reasonably certain how to go about them. One privilege of being an adopted son of Julius Caesar, after all, had been the possibility of an education bounded only by his own thirsty mind. By the time he’d left Rome a year ago, a tutor had proudly proclaimed him one of the most widely read men in the city—and that was before the old scrolls and tomes Juba had encountered during these many months across the sea in Africa.

Still, the idea of using violence to attain what he wanted didn’t appeal to him. He doubted that information wrought from torture could really be of much use. It would be too conflicted. And even more than that, it didn’t seem right. It didn’t seem, well, Roman.

A hard wind kicked up the cliff-side, bringing with it the smell of brine from the churning waters far below. Gazing down at his arms after the stinging mist had passed over him, Juba noted the little pale droplets clinging to his dark skin. The irony of it further clouded his brooding mind. I’m no Roman, he thought. I’m a Numidian.

Juba heard the sound of someone moving hesitantly down along the narrow, broken path behind him. Even without turning, he could tell it was Quintus. The slave disliked heights. Always had. And now that the years had brought gray to his temples and long lines to his face, loyal Quintus truly hated them. “Yes?” Juba asked.

“It’s Laenas, sir. I think he’s … well, growing impatient with the priest. I fear something rash.”

Juba nodded. He’d expected as much when he’d left them alone in the old temple. Scar-faced Laenas had proven, time and time again during this past year, that he could be counted on for only two things: to desire coin and to despise those who stood in the way of his getting it. Since Juba had promised him thirty silver denarii if they got the information they were seeking from the Numidian priest, he was bound to be impatient.

Juba turned back from the salty, whipping wind, saw that Quintus was huddled as close to a nearby boulder as he could manage. Despite his own gloomy thoughts, Juba couldn’t help but smile at the old slave. Assigned to care for him when he was still just a child living in Caesar’s villa, Quintus had grown to be more a father to him than Julius had ever been.

“Very well,” Juba said, stepping forward to help his slave back up the path toward the temple. “Let’s hope he’s willing to talk now.”

Cut back into the earth, the old temple dedicated to the pagan goddess Astarte appeared from the outside to be little more than a weather-beaten cluster of stones clinging to the cliffs just below the crest of the bare ridgeline. Quiet. Isolated. Just the sort of place to hide the secrets of ancient gods.

Juba ducked through the clanking wooden door, grateful to be out of the wind and into the relative warmth of the dark, windowless interior. Quintus was quick to follow, the release of his breath signaling his additional relief at being off the precipices outside. “They’re still in the back,” the slave whispered.

Juba moved quickly through the small, bare antechamber and then through a thick drape into the lamp-lit altar room beyond, its air filled with the heavy scents of spiced incense and moist loam. At its head sat a low stone firepit filled with ash and bones. Behind it, atop a rough-hewn wooden pillar blackened by the fire, sat a small clay statue of a woman, only a little taller than his forearm, perched on a throne and holding a bowl beneath her more than ample breasts. Juba had read of such figurines in his books. It was said that the power of the fertility goddess—and her associated priest, of course—could be seen in the miraculous leaking of milk from the statue, flowing down from her breasts into the bowl.

Juba had studied this particular statue carefully earlier in the day, while they waited for the priest to return from the well in the village. He’d had no trouble finding the small holes bored through the clay nipples into the hollow of her body. He’d even found some flecks of the soft wax plugs that the priest had used to keep her breasts from leaking until the sacrifice burning in the altar below her had melted them.

So much for this god, he’d thought.

Juba walked past her now, up the three worn steps of the altar’s stone dais, and then down another set of steeper, more roughly hewn steps that led to a low doorway against the back wall. Pushing through the drape there, he entered the last chamber.

The old priest of Astarte, still bound to his simple stool, had fallen over to the damp earthen floor. His nose was running with blood that glistened wetly in the flickering lamplight, and the short but stout Laenas was straddling him, hunched over at the waist, his fist raised for another strike.

“That’s enough,” Juba said, trying to sound strong, and glad to hear that his voice didn’t crack.

Laenas grunted his assent and stood. Juba noticed now that his other hand had been holding a knife, which he quickly slipped back into the folds of his clothing. Its edge did not yet appear wet. “We was just talking,” Laenas said over his shoulder.

The priest coughed loudly, a half-retching sound from his gut, and then spat into the dark dirt. Juba had always found it difficult to judge the age of those men older than him, a problem compounded here by the leather-tanned skin of a native Numidian: though it was, Juba could never forget, the tone of his own flesh, it nevertheless appeared foreign to his sight. Still, from the man’s wrinkled face, his sparse, white hair, and his thick beard, Juba had guessed him to be in perhaps his seventies, even if his ability to withstand threat—and to manage the long hike to the village for water and supplies—spoke of a younger man, at least in spirit. Looking at him, Juba felt a pang of pity, but not remorse. “Help him up,” he said.

Laenas grunted again—the typical depth of his speech—and then stepped around to lift the priest and his stool back into position. It seemed no more difficult for the stout little man than hoisting a sack of wheat. As the old man was lifted upright, Juba saw again the strange symbol on the pendant hanging around his neck: a triangle inscribed, point down, upon a perfect circle. He had seen similar pendants around the necks of some of the men whose information had led him here.

“I’m sorry for that,” Juba said, measuring out his words, concentrating on keeping his back straight, his chin high. “We’re all just very anxious to hear what you have to say. Laenas here most of all.”

The priest sputtered, his mouth moving, but he said nothing.

Juba sighed and walked over to one of the priest’s rickety tables. It had been unceremoniously swept clean, the plates and parchment tumbled to the floor. In their place sat a bundle of bound canvas—substantially bigger, Juba noted with some amusement, than the statue of Astarte in the hall. Juba walked to it and raised his hand to touch the rough cloth, feeling the outline of the broken wooden staff beneath. Where the staff met the wider metal head, the cloth felt warm, and he snatched his fingers away with a start. He swallowed hard, glad his back was turned to the other men in the little room. “Let’s start simple,” he said, trying to calm his heartbeat. “This staff. This … trident. How did it come to be here? The priests who pointed me here say it’s the Trident of Neptune—or Poseidon, if you prefer. Is that true?”

When the priest said nothing, Juba turned around and saw that he was shaking his head weakly. Standing behind him, Laenas’ face appeared to flush, the wide scar across his right cheek a darkening purple in the gloom.

“It’s strange, you know,” Juba continued, looking back toward the bundle and resisting the urge to touch it this time. “An artifact of the old Greek and Roman gods, here in this place, in the possession of a priest of Astarte. I wonder … is there something to the idea that Astarte is the same goddess as the Greek Aphrodite, the Roman Venus?”

“I’ll not help Rome,” the old man croaked.

Juba heard only the briefest rush of movement before the priest gasped, a sound that reminded the young man of a cook tenderizing meat. Juba spun around and saw the old man slumped sideways, grimacing. “Laenas!” he cried out, his voice cracking with the sudden start.

The rugged Roman straightened, his fist coming back from the priest’s side and something like a smirk momentarily passing over his face. “Wasn’t having him spitting about Rome,” he said.

As if in reply, the priest did, in fact, cough and spit. The blood ran dark streaks into his matted beard.

Whatever else Juba might have expected the priest to utter then—that the Trident wasn’t real, that the gods weren’t real, maybe that he had money hidden away under a rock somewhere—it wasn’t what the old man finally managed to say. “You’ve your father’s eyes.”

Juba stared at him, unblinking, his mind and heart racing. The old man held his gaze for a long moment before shutting his own eyes in a grimace of pain. Juba still stared at him, feeling the attention of Quintus and Laenas upon him even as he dared not look at them.

“Lord Juba—” Quintus started.

“Leave us,” Juba commanded, cutting off the slave. He flicked his gaze at Laenas just long enough to note the familiar look of disdain on the rough man’s face, the same twist of jealousy and disgust he’d seen so often while growing up in Rome as the foreign-born adopted son of Caesar. “Both of you.”

“My lord, I—” Quintus said.

Juba silenced him with a wave of his hand. “I said go. Now.”

“Very well,” Quintus said, bowing deep as he backed toward the doorway. Laenas followed with a predictably dissatisfied grunt.

In seconds, Juba stood alone in the little room with the sagging priest. He took long, deep breaths to steady himself. “You speak the language of Rome well for a Numidian,” he said when the sounds of Laenas and Quintus had grown faint.

The old priest licked his lips and swallowed before responding. “I was a slave to Rome, too, once.”

“What’s your name?”

“Syphax,” the old priest said.

“So you knew my father.”

Syphax nodded slowly. “I knew the king, yes.”

The king, Juba thought. Could it truly be that the old priest, hidden away out here on this lonesome spit of land, was a loyalist to the royal family of Numidia? The lineage of which he alone remained?

“I saw him die,” Syphax said.

“What?”

The old priest coughed twice painfully before he regained his composure. “Saw him die on the blade of my master, Marcus Petreius.”

Juba staggered backward into the ragged table behind him as if physically struck by the sheer weight of memory and history that flooded into his mind. He’d read the books, sought out every shred of detail he could find on his real father’s inglorious end. After Caesar had defeated the Numidian army at Thapsus, Juba’s father had fled with the general Petreius, only to be trapped. The histories spoke of how the two men dueled to the death, opting for an honorable end rather than the wrath of Caesar and the horrible, dishonorable Triumph that he would have put them through back in Rome—the Triumph that had thus fallen to his infant son, Prince Juba, first seized and then later adopted by the very man who’d driven his royal father to such a doom.

“No,” Juba managed to say. It had only been two months since Juba had knelt, at last, beside the unmarked grave of the true father Caesar had never let him know. His hands gripped the rough wood of the table at his back. “You cannot have.”

“I watched them fight at the end,” Syphax said. There was no pride in his voice. No power. Only old sorrow. “Petreius was still alive when it was done. As my duty, I ran a blade into his heart.”

Juba closed his eyes, tried to imagine the scene as he had so many times in his young life. As ever, his father’s face was a blur. Only the darkness of his skin was familiar. But he could picture a younger Syphax there, too, waiting, with a shined and sharpened sword, for either of them to fall. “Yet here you live,” Juba said, opening his eyelids to glare fiercely at the priest. “A slave … you killed your master but didn’t follow him.”

The priest’s jaw quivered, his eyes red and sunk deep into tired sockets. “You’re right. I didn’t. I promised to fall upon my own sword after it was done. Promised them both. But I didn’t.”

Juba was just Roman enough to know the depth of Syphax’s dishonor on principle. He was just Numidian enough to think the offense against his true father’s memory worthy of death. And he was just young enough to act on the impulse of rage that washed over him.

He opened his mouth to call for Laenas.

“But for good reason, Juba!” Syphax cried out in a ragged voice. “I couldn’t let them get it. I couldn’t!”

The old priest’s eyes had a trance-like glaze now, riveted on the bundle of cloth on the table. Juba, despite his rage, decided not to call Laenas just yet. “Tell me of it,” he said. “Tell me everything.”

Juba stepped around the altar to Astarte, canvas bundle under his arm, and found Quintus and Laenas in the temple’s main room, sitting on one of the primitive stone benches. The old slave looked anxious. Laenas just looked sullen. Juba ignored them both for now, walking past them and through the antechamber out into the wind and the smells of the sea, his head too full of thoughts to speak just yet.

Syphax had indeed told him all that he knew. Juba was certain of that. The old man’s despair was too great to hold back to the son and heir of Numidia, especially once he knew the secret Juba had kept from everyone but Quintus: that he hated Rome, that he hated his adopted father. He hated them for his real father’s death. For the disgrace of the Triumph that was his earliest memory. For everything that Rome had done to his country.

Syphax had told him everything then. He’d told him far more than he could ever have imagined.

The Trident in his hands was indeed the weapon of gods. Poseidon. Neptune. But more than that, it was a weapon of the Jews, whose strange religion Juba knew little about—a fact he intended to remedy as soon as possible with the help of every book he could get his hands on.

And still more: there was an even greater weapon of the gods out there to be found, a weapon of the Jews that might give him the power to accomplish the revenge he’d long hoped to achieve. An ark.

The wooden door to the temple squeaked open and shut. Quintus tentatively shuffled up behind him. “Juba?”

The sixteen-year-old focused his eyes on the distant horizon, where the darkening sea met the darkening sky. Lightning flashed there, silent but threatening.

Syphax didn’t have all the answers, but the old priest knew who did. “Thoth knows,” he’d said, again and again. The source of the Trident’s power, the nature of its strange black stone, the whereabouts of the wondrous ark … Thoth knows.

At first, Juba had thought it was no answer at all. Thoth was an Egyptian god, like the Roman Mercury, a figure that moved between the world of gods and the world of men. A deity of so many faces he seemed to be everything and nothing all at once: god of magic and medicine, god of the dead, god of the moon, god of writing and wisdom, even the founder of civilization itself.

Thoth would naturally know the answers to questions. Yet Syphax had spoken with a pragmatic earnestness, as if Juba could easily get information from Thoth.

“So where is Thoth?” Juba had asked the priest of Astarte.

And, after some final persuasion, Syphax had answered: “Thoth was in Sais.”

Sais, Juba knew, was the cult center for the goddess Neith, the Egyptian counterpart of Astarte, which explained the priest’s knowledge. Perhaps it even explained how he’d come to have the Trident. Then he’d caught the nuance in the priest’s words. “Was?”

The old priest had smiled grimly, his pale teeth smeared with red. “The Scrolls are in Alexandria.”

The truth at last. It wasn’t Thoth himself who had the answers, but the legendary Scrolls of Thoth, in which all knowledge, it was said, could be found. And the Scrolls were in Egypt, in the Great Library. Find them and he’d have the power, and the vengeance, that he sought.

“Juba?”

The lightning pulsed again, and beyond the wind and the breaking of waves Juba heard a quiet rumble. Was it from the earlier flashes? Or was it the deep of the sea, calling out for its master? Juba swallowed hard, resisting the temptation to touch the metal head of the Trident in its canvas bundle, to see if it was warmer now. Instead he took a deep breath to clear his mind, to focus on the tasks immediately at hand. He needed to do more research. More than that, he needed money. Getting the Scrolls of Thoth from the Great Library and destroying Rome wasn’t going to come cheap, after all, with or without a weapon of the gods. And there was surely no better time to strike than now, with war between Rome and Alexandria threatening to turn the world to chaos.

“We’re returning to Rome,” he said over his shoulder. “As soon as possible. There are things I need to do there.”

“Of course,” Quintus said, his voice uncertain. “Laenas wants to know, sir, what about the priest?”

Juba blinked away the beads of salty water that were starting to cling to his eyelashes. What to do about the priest? He was a loyal Numidian, after all, one of the very people Juba was going to save from Rome. Yet he’d abandoned the promise made to Juba’s father, no matter his reasons. And, truth be told, he knew far too many things that were best kept secret, even if Juba didn’t yet know the fullness of his course. Viewed through the lens of logic, the decision was easy, even if saying it was hard. Juba wondered if his Numidian father had ever felt the same. No doubt his adopted Roman one never had. “Tell Laenas to kill him,” he finally managed to say. As the words escaped his lips Juba knew for certain that he would not sleep well this night. He wondered how he would ever sleep soundly again. “Tell him he’ll get his thirty coins if he does it quickly.”

Quintus hesitated for a moment, a slight stammer his only response. Then Juba heard the sound of the temple door opening and closing again, leaving him alone.

Well, perhaps not alone, Juba corrected himself, watching the approaching storm and wondering whether the gods were real.

Copyright © 2015 by Michael Livingston

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

The Atlas Six by Olivie Blake (paperback)

The Atlas Six by Olivie Blake (paperback) Mistborn: Secret History by Brandon Sanderson

Mistborn: Secret History by Brandon Sanderson The Genesis of Misery by Neon Yang

The Genesis of Misery by Neon Yang Growing Up Weightless by John M. Ford; introduction by Francis Spufford

Growing Up Weightless by John M. Ford; introduction by Francis Spufford The Witch in the Well by Camilla Bruce

The Witch in the Well by Camilla Bruce The Spare Man by Mary Robinette Kowal

The Spare Man by Mary Robinette Kowal Mystic Skies by Jason Denzel

Mystic Skies by Jason Denzel The Atlas Paradox by Olivie Blake

The Atlas Paradox by Olivie Blake Ocean’s Echo by Everina Maxwell

Ocean’s Echo by Everina Maxwell Legends & Lattes by Travis Baldree

Legends & Lattes by Travis Baldree Origins of the Wheel of Time by Michael Livingston; foreword by Harriet McDougal

Origins of the Wheel of Time by Michael Livingston; foreword by Harriet McDougal Blood Moon by Heather Graham and Jon Land

Blood Moon by Heather Graham and Jon Land The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe

The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe The Lost Metal by Brandon Sanderson

The Lost Metal by Brandon Sanderson Alone With You in the Ether by Olivie Blake

Alone With You in the Ether by Olivie Blake