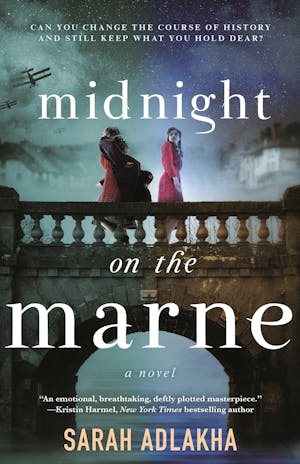

Set during the heroism and heartbreak of World War I, and in an occupied France in an alternative timeline, Sarah Adlakha’s Midnight on the Marne explores the responsibilities love lays on us and the rippling impact of our choices.

Set during the heroism and heartbreak of World War I, and in an occupied France in an alternative timeline, Sarah Adlakha’s Midnight on the Marne explores the responsibilities love lays on us and the rippling impact of our choices.

France, 1918. Nurse Marcelle Marchand has important secrets to keep. Her role as a spy has made her both feared and revered, but it has also put her in extreme danger from the approaching German army.

American soldier George Mountcastle feels an instant connection to the young nurse. But in times of war, love must wait. Soon, George and his best friend Philip are fighting for their lives during the Second Battle of the Marne, where George prevents Philip from a daring act that might have won the battle at the cost of his own life.

On the run from a victorious Germany, George and Marcelle begin a new life with Philip and Marcelle’s twin sister, Rosalie, in a brutally occupied France. Together, this self-made family navigates oppression, near starvation, and unfathomable loss, finding love and joy in unexpected moments.

Years pass, and tragedy strikes, sending George on a course that could change the past and rewrite history. Playing with time is a tricky thing. If he chooses to alter history, he will surely change his own future—and perhaps not for the better.

Midnight on the Marne will be available on August 9th, 2022. Please enjoy the following excerpt!

CHAPTER ONE

Marcelle

Soissons, France

September 1914

The winds shifted outside the window as the light faded, the burdens of the world clawing at Marcelle’s beautiful life and trying to rip it to shreds. She was dutiful in her indifference to it, ignoring the empty house around her with a steadfast determination.

She dreamed, instead, of Pierre. She occupied her thoughts with stolen kisses, secret engagements, and romantic wars. Not the kind of war that took place on battlefields and in trenches, not the kind that men wrote of. She dreamed of the war she had envisioned when the Germans had first announced their intentions to invade France: the soldiers in their crisp uniforms; the troops in their perfect formations; the lovers in their final embraces. She would be a soldier’s wife soon, and what could be more romantic than that?

Pierre had left for the front just two days earlier, along with Marcelle’s brothers, and, while the proposal hadn’t yet been announced, she was certain that when they all returned for Christmas in a few short months, it would become official. She would be eighteen next year, old enough to be a bride.

Madame Fournier.

The name tasted sweet on her tongue, like the candies her father had brought home from the store last year after Madame Martin’s nephew had visited with an armful of goodies from America. He had bartered them for an expensive bottle of Bordeaux from her father’s cellar, and Marcelle had never tasted anything sweeter.

But that was before her father changed, before everything changed. Her brothers had tried to explain the dynamics of the war to them at supper the night before they’d left, but it was a convoluted tale, and Marcelle wasn’t certain they’d understood it themselves. From what she had gathered, the archduke of Austria had been assassinated by Serbians three months earlier, leading to a war that pitted one faction of European countries against another. Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Turkey were the aggressors, while France had allied itself with Russia and Great Britain to defend Serbia.

Marcelle’s father had said it was a bit like a chess match, but Marcelle thought it sounded more like a schoolyard brawl, just a bunch of bullies taking sides and fighting. What it boiled down to for her was that two days earlier, her fiancé and her brothers had been marched out of town to defend their northeastern border with Belgium, not one hundred kilometers away, because Germany was poised to strike.

Marcelle felt certain that the Germans were in for a devastating defeat. How could they fight a war on two fronts? Russia to their east; France and Great Britain to their west. The boys would be home before Christmas. She was sure of it.

The sun continued to sink outside the window, but Marcelle waited until the sky had almost succumbed to darkness before she wrapped a shawl around her shoulders and walked the short distance from their home to her father’s store down the street. The shop was empty when she arrived, so she followed the soft light filtering in from above as it guided her down the stairs to the cellar. The jewelry box was the first thing she noticed. It sat on the wooden table against the far wall of the room, looking out of place by the sacks of food that had been tossed down beside it: potatoes, flour, sugar, beans.

“Que fais-tu?” Marcelle asked. What are you doing?

From a darkened corner just beyond the light’s reach, her mother stepped forward.

“Nothing, dear,” she said. “Just tidying up. Doing some rearranging.”

“Stop lying to her, Eva.” The wine bottles clinked as her father stacked them beneath the wooden table, his temper in full bloom. “She is practically a woman. We need everyone’s help here. Stop trying to shelter her from this.”

“Shelter me from what?” Marcelle stepped forward, eyeing her sister, who was handing the bottles to their father. Rosalie was an obedient girl. Despite sharing their mother’s womb and every minute of their lives thereafter, they had so little in common.

Marcelle was five when she had first realized they were special. She had seen her reflection in her mother’s mirror at home, so she knew it was the same as her sister’s, but it was not until her mother had taken them to the river for a picnic on their fifth birthday, and she’d seen their reflections side by side in the pool of water, that she had really understood what they were: two different versions of the same person.

Marcelle was the achiever. Nothing was beyond her reach. She was one of the few girls in Soissons to complete her second-level examinations, and she excelled in her studies, eager to learn every nuance of history and language and mathematics. Her plans had once included making the one-hundred-kilometer trek southwest to Paris upon her eighteenth birthday to find work as a teacher. She had never shared that dream with anyone. Her parents would have discouraged it, and by the time her second-level examinations had rolled around, she had already fallen for Pierre.

Rosalie, by contrast, was the pleaser. She was a quiet and serious girl, sullen, to a certain extent, especially since talk of war had arrived at their doorstep. Life was a chore for Rosalie, a tedious undertaking that required following all the rules in all the right order. She would never have dreamed of running off to Paris without their father’s permission. She did what was expected of her.

“Come, dear,” her mother said, smoothing her hair back and pinning the strays into place before gripping Marcelle’s elbow. “Let’s get you back home. The air down here is not good for you.”

“No.” Marcelle pulled her shoulders back and straightened her spine, pressing her heels firmly into the soft earthen floor and standing almost as tall as her mother. “I demand to know what is going on here.”

“You demand to know?” Her father almost banged his head on one of the low-hanging beams of the ceiling when he spun around. “You are a little girl with her head in the clouds. Open your eyes if you want to see what is happening here. The Germans are coming. If they have not already killed your brothers or taken them hostage, they will do so tomorrow. And then they will be here. They will destroy our town and take what they want, and we will be at their mercy.”

Marcelle stepped back at the assault of his words.

“You want to know what we are doing here?” he continued. “We are trying to survive. We are trying to save our family. And your sister is the only child I have left who is strong enough to help me do that.”

“Mon Dieu, Gabriel!” Her mother stepped between them, wrapping an arm around Marcelle and forcing her up the stairs. The light from outside was muted when they crested the final step and entered the store, and it wasn’t until Marcelle looked around that she spotted the crisscrossed mesh that had been taped to the windows. She hadn’t noticed it when she had entered just moments earlier, or the bare shelves, or the silence.

The streets were empty. The men who spent their afternoons smoking and arguing and laughing outside of the store were missing, the women who shuffled arm in arm from shop to shop were gone, and the children who chased the dogs from one side of the cobblestone street to the other were nowhere to be seen. When had this happened?

“What is that?” Marcelle pointed to the mesh that was taped to the windows.

“It is to prevent glass from shattering and spraying into the store.” Her mother hesitated before she continued. “If the Germans shell us, we need to be prepared.”

Marcelle simply nodded and followed her mother home in silence. She sat on the mattress she shared with her sister, the one her brothers had once shared, and tried not to imagine where they might be now. She tried not to think about Pierre and the letters she had already written to him. She tried not to hear their voices or see their faces. She tried, but her father’s words would not leave her: If they have not already killed your brothers . . .

She didn’t come out for supper that night. Her mother tried to take her some bread, but Marcelle refused to eat. She refused to speak or change her clothes or acknowledge her sister when she came to bed. Her father was right. She was a naïve little girl with her head in the clouds. She had refused to see the signs all around her. She had sent the men in her life off to war believing they would return safely to her.

But hadn’t they deserved that?

For all she knew, her father was mistaken. He was not the Almighty; he could not possibly know their fates. He was a man like any other man, and Marcelle would keep her head bowed in prayer to the heavenly Father, who did know the fates of all men, the Father who could perform miracles and was the only One who could deliver her brothers and her fiancé from evil.

The thunder started shortly before dawn. Marcelle didn’t realize she’d fallen asleep until the booming in the distance woke her. The storm was far enough away that the rains would not reach them for at least another hour, so she pulled the quilt her grandmother had made and gifted to her parents on their wedding day up under her chin and curled into a tight ball. She would sleep until daylight stole the darkness.

The rains never came that day, because the thunder was not born from the heavens. To the west, the sky remained a cerulean blue, but to the east, a haze of smoke floated above the horizon where men were killing men and families were fleeing for their survival.

Rosalie was the one to drag her out of bed and hand her a bag so she could pack two days’ worth of clothing. Marcelle followed her back to their father’s store and down the cellar stairs to where their family would wait out the long days ahead. She didn’t argue with her sister. She didn’t argue with anyone. She stepped in line and did as she was told, clutching her grandmother’s quilt to her chest as she watched some of the men from town help move mattresses to the cellar.

Monsieur Fournier was one of the men. Pierre’s father was forty-six, just like Marcelle’s, and they had both avoided being sent to the front by the grace of age. Soissons seemed to be shrinking by the day. The absence of the young men was made more obvious by the disappearance of families who had fled toward Paris as the Germans neared. Marcelle had overheard her father discussing similar plans with Pierre’s father, but Monsieur Fournier wasn’t ready for it yet; he was worried his daughters would not be strong enough. As she sank down onto the mattress beside her mother, who was cutting an apple and portioning the pieces onto plates for the men, Marcelle wondered if her own father felt the same way about her.

“Do you think I am weak?” Marcelle reached over and slipped one of the apple slices into her mouth before her mother could swat her hand away.

“I think this world does not suit you,” her mother replied, replacing the apple slice before moving the plate out of Marcelle’s reach.

“Is that why you tried to shelter me from it? Because I am not strong enough?”

“Not at all. You are stronger than you give yourself credit for.” She took a bite of the last apple slice before handing the rest to Marcelle. “Your father does not think you are weak, either. He is simply trying to protect you, and he is worried that you are not as careful as your sister. You speak up when the world expects you to be quiet. This could get you into trouble one day. You do not have your brothers to protect you anymore.”

“But I heard some of the men talking earlier, and they said there is still a chance that the boys are alive out there.”

Her mother nodded. “I hope they are right,” she said. “There is no greater sorrow than losing a child.” She squeezed Marcelle’s hand before she continued. “You will be such a beautiful mother one day.”

It was not until late in the night that Marcelle really thought about her mother’s words. The thunder grew louder as the shells rained down around them, and, while silence filled the space between blasts, Marcelle knew that no one slept.

She couldn’t stop hearing her mother’s words: You will be such a beautiful mother one day. Did she really believe that? Or did she think that cellar would be their tomb?

The night stretched on indefinitely. Pierre’s parents had taken refuge with them, along with their two young daughters, Lina and Marie, who whispered to each other in English until the lanterns were extinguished. Marcelle wondered what they were saying. Were they comforting each other? Were they scared? They were shy children, always giggling when Marcelle came around. Pierre’s grandmother was British and had insisted that her grandchildren be raised to speak English, but Marcelle had never heard either girl speak French, and she often wondered if they even knew how.

The cellar was only large enough for four mattresses since Marcelle’s father had refused to move the wine bottles or the wooden table against the far wall. Sleeping conditions were tight, to say the least, and though no one made a sound all night, Marcelle felt certain it wasn’t because anyone slept. It wasn’t until her father pulled the cellar hatch open, and a current of fresh air swept in around them awakening all the stagnant fears and anxieties that had festered throughout the night, that anyone stirred.

Marcelle clambered up the cellar stairs after her father, so desperate for air that she didn’t even bother with shoes. A glint of sunlight reflected off a fractured window that had not survived the night, and before she could blink away the glare, she knew she had made a grave mistake by following him.

German.

The man standing beside her was speaking German. She recognized his voice and understood his words, but she couldn’t force a breath into her lungs, and the tunneling of her vision was threatening to land her on the ground at his feet.

“Hier spricht niemand Deutsch.” No one speaks German here.

Monsieur Bauer. It was her German teacher from school, lying to the German soldier by his side about one of his most accomplished students. He had written that on her final evaluation not even two months earlier: Mlle. Marchand is gifted in conversational German. She is one of the most accomplished students I have had the pleasure of instructing. He was the one who had told Marcelle about the all-girl schools in the bigger cities and the boardinghouses for unmarried women who dedicated their lives to the education of children, the one who had placed those dreams of independence in her head all those years ago. He had not been happy when Marcelle’s attentions had shifted from school to Pierre.

“Monsieur Marchand,” he said, addressing Marcelle’s father in French and gesturing to the German soldier accompanying him. “Hauptmann Krause here has asked that all citizens of Soissons be present outside the cathedral at midday today for an important announcement. He has also commanded anyone who speaks German to come forward and assist as a translator for his troops who will be billeting in the homes along this street. I have already informed him that no one in your family speaks German and that your house is available for his troops.”

Marcelle’s father nodded along to Monsieur Bauer’s words, skillfully avoiding the gaze of the German soldier, who, judging from the medals weighing down his coat, must have been someone very important.

Marcelle could feel the man’s eyes on her. She hadn’t thought to pin her hair up before leaving the cellar, and she wasn’t even sure she had buttoned her blouse up around her neck. She felt exposed and vulnerable, and despite the chilled morning air, beads of sweat formed on her upper lip. She stood frozen in place, her senses heightened like a doe caught in the sights of a wolf, wondering if the predator beside her was waiting for her to bolt, if he delighted in the chase.

“Oui, Monsieur Bauer.” Marcelle’s father nudged her back toward the cellar. “Our house is open for the troops. We will gladly take comfort in the cellar, and I will be certain to spread the word about the meeting at the cathedral today. Merci.”

Marcelle didn’t notice the musty stench of the cellar when she descended the stairs, or the darkness that enveloped them when her father closed the hatch. The cold of the tomb-like stone walls and the dampness that endlessly clung to them was a welcome relief. It wasn’t until her father lit the oil lamp that she had to face her consequences.

“You will be more careful from now on.” His voice never rose above a whisper, but venom laced his words. Marcelle did not fault him for it. She had been reckless. She had not been paying attention, but she would not make that mistake again.

“Oui, Papa,” she mumbled, ducking into the shadows and feeling her way to the mattress she shared with her sister.

The glow of the oil lamp reached only as far as the adults who gathered around it, her parents and Pierre’s. From the periphery, Marcelle and Rosalie watched its shadows dance across their faces, unmasking the fear they tried so desperately to hide. The cellar wasn’t big enough for privacy.

Plans were being made. Besides the meeting at the cathedral square, there were supplies to gather and families to visit and meals to be made. As expected, Marcelle’s chores—childcare and meals—would never bring her out of the cellar, but she was wholly unprepared for the task her sister would soon inherit.

Rosalie jumped at her father’s words, always eager to please him. She was, without question, his favorite daughter. Maybe even more revered than their brothers. Through the anemic glow of the oil lamp, her sister’s eyes shined with pride.

“You will come with us to the meeting at the cathedral square today,” her father said. “And from there, you will accompany Monsieur Fournier to fetch a wagon and some food supplies from his storage shed.”

“No.” Marcelle’s words were cutting through the thickness of the cellar air before she’d realized she was even speaking. “You cannot mean to send her out there with the Germans. I will not let her go.”

“This does not concern you, Marcelle.” Her father’s eyes flashed to the darkened corner, but Marcelle was already at her sister’s side.

“Of course it concerns me. I will not let you send her out there. You saw how that German looked at me. It will be the same for Rosalie.”

“Rosalie can handle herself. We have no other choice.”

“Why can’t you do it? Or Maman? Or Madame Fournier?”

“Enough, Marcelle.” If not for the company of the Fourniers, her father would not have been so charitable with his patience. His voice trembled with contempt. “There are other tasks that need to be done, and Madame Fournier’s children need her here. This is not open for discussion.”

“Then I will go with her.”

“You will not!” When his hand slammed onto the wooden table between them, Marcelle was silenced into submission. “You are a reckless child. You think nothing through, and one of these days your carelessness will get people killed. You will not leave this cellar until I tell you it is safe. Do you understand?”

Marcelle slunk to the mattress in the corner without answering him, but she could feel him pressing into the darkness, hovering above her, and refusing to relent without her promise.

“Do you understand me, Marcelle?”

“Oui,” she mumbled, but turned her body away from him. She would say whatever words he needed to hear, but she would not abandon her sister. She would never send Rosalie out to the wolves on her own.

Click below to pre-order your copy of Midnight on the Marne, coming August 9th, 2022!

The Last Crown

The Last Crown

Micro by Michael Crichton and Richard Preston

Micro by Michael Crichton and Richard Preston

Lightning Shell

Lightning Shell

She Wouldn’t Change a Thing

She Wouldn’t Change a Thing

An Irish Country Doctor

An Irish Country Doctor

Hollow Empire

Hollow Empire Deuces Down

Deuces Down

The Wood Wife

The Wood Wife Dealbreaker

Dealbreaker

A Summoning of Demons

A Summoning of Demons The Best of R.A. Lafferty

The Best of R.A. Lafferty Engines of Oblivion

Engines of Oblivion

Silence of the Soleri

Silence of the Soleri Fairhaven Rising

Fairhaven Rising

The Shadow Commission – The Dark Arts Trilogy – David Mack

The Shadow Commission – The Dark Arts Trilogy – David Mack