opens in a new window

Written by opens in a new windowKathleen O’Neal Gear and W. Michael Gear

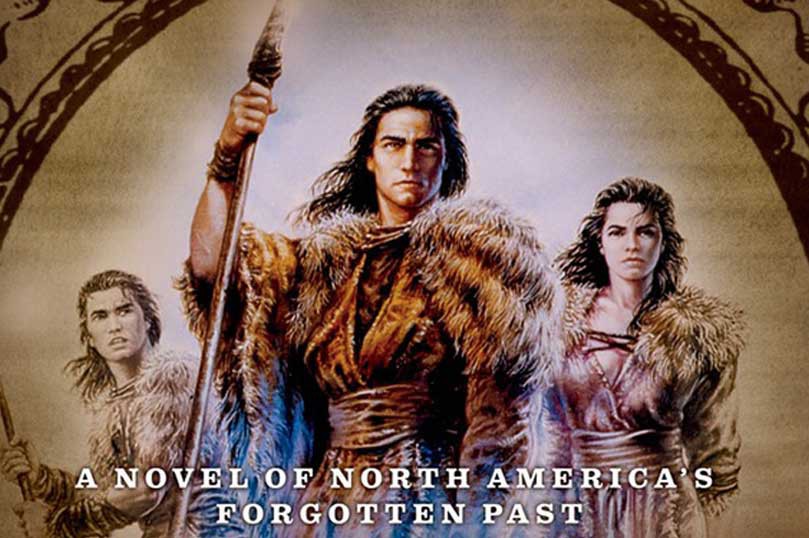

This July marks the twenty-five year anniversary of the publication of opens in a new windowPeople of the Wolf. We thought we’d tell you how it came to be.

Greetings! We are W. Michael Gear and Kathleen O’Neal Gear, the authors of the opens in a new windowNorth America’s Forgotten Past series. While we are both academically trained archaeologists with nearly sixty years of combined field experience, it wasn’t a foregone conclusion that we would write a unique series of novels based on the archaeology of the US and Canada.

This story starts in 1986 when Michael sold his interest in Pronghorn Anthropological Associates, the archaeological research firm he had co-founded, and Kathleen resigned from her position as an archaeologist for the U.S. Department of the Interior. Between us we had an impossibly small nest egg, a rustic cabin with no running water high in the Colorado Rockies, and the impossible dream that we were going to be novelists. (To you aspiring ascetics out there: you discover the true meaning of life when you lower your delicate nether regions onto an outhouse frost ring at -35F.)

It was tough going. Income was scarce. In February of 1988 we were down to our last $184.47. The cupboards and freezer were bare. Road kill along the highway was starting to look really appetizing.

At this critical moment, our good friend Bill Davis, principal investigator at Abajo Archaeology, called us: “Guys, I’m in a fix. I know it’s the middle of winter, but I need to field a team of archaeologists on the I-70 expansion project in central Utah. We’ll be paying top wages.”

We loaded the truck the next day and spent a month and a half digging archaeological sites along the I-70 right-of-way across the San Rafael Swell.

Back at the cabin, we had barely stepped in the door when the phone rang.

“Where you been?” Tor Books editor Michael Seidman asked. We’d met Seidman in June at a Western Writers of America conference in Fort Worth, Texas.

“Doing archaeology in Utah.”

“What did you find?”

“Well, a lot, including maybe the oldest house pit in Utah. Could be 6,000 years old. Dates are still out. Even the roofing is intact. And then there were Fremont culture storage pits with the piñon nuts still inside, and Fremont pit houses, and gaming pieces—”

“Why aren’t you writing about all this?”

“Our agent told us no one cared about America’s past.”

“I care,” Seidman said. Then he thought for a moment before adding, “I want a hefty book to put in my hefty bag, while I walk the hefty streets of New York. About five hundred pages. Start with the first migration into North America and have each of the characters become the founder of one of the modern Native American languages. Then, in the last scene of the novel, they see a European ship floating off the East Coast.”

“Uh, Mike, let’s get this straight. You want us to write a novel that spans the North American continent, covers fifteen thousand years of cultural history, and contains hundreds of characters. In five hundred pages.” Keep in mind, Bill Davis hadn’t paid us yet. We still had $184.47 in the bank. We said, “We’ll do it. But with that much to cover it will have a plot as engrossing as the phone book.”

There was silence on the line.

Finally, Seidman said, “Well, what would it take to just skim the high points?”

We settled on six novels. The series would focus on PaleoIndian culture, two archaic-period novels, one book each on the Hopewell, Cahokia, and the Chaco Anasazi, finishing with a California book. It was too good to be true. Somebody was finally going to let us write about what we loved.

And here we are today, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the publication of People of the Wolf. The series was, and remains, unique. In many ways, we’re telling the story of a continent’s forgotten past. Our continent’s. Our peoples’. It’s twenty-two books later, and we’ve still just barely scratched the surface of North America’s amazing and rich prehistoric heritage.

We owe a great debt of gratitude to our publisher, Tom Doherty, who took a chance that two archaeologists could actually write novels.

Thanks, Tom.

The ebook edition of People of the Wolf is on sale for $2.99 until Friday. Get your copy now!

Buy People of the Wolf today:

opens in a new windowAmazon | opens in a new windowBarnes & Noble | opens in a new windowBooks-a-Million | opens in a new windoweBooks.com | opens in a new windowGoogle Play | opens in a new windowiBooks | opens in a new windowIndiebound | opens in a new windowPowell’s