opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

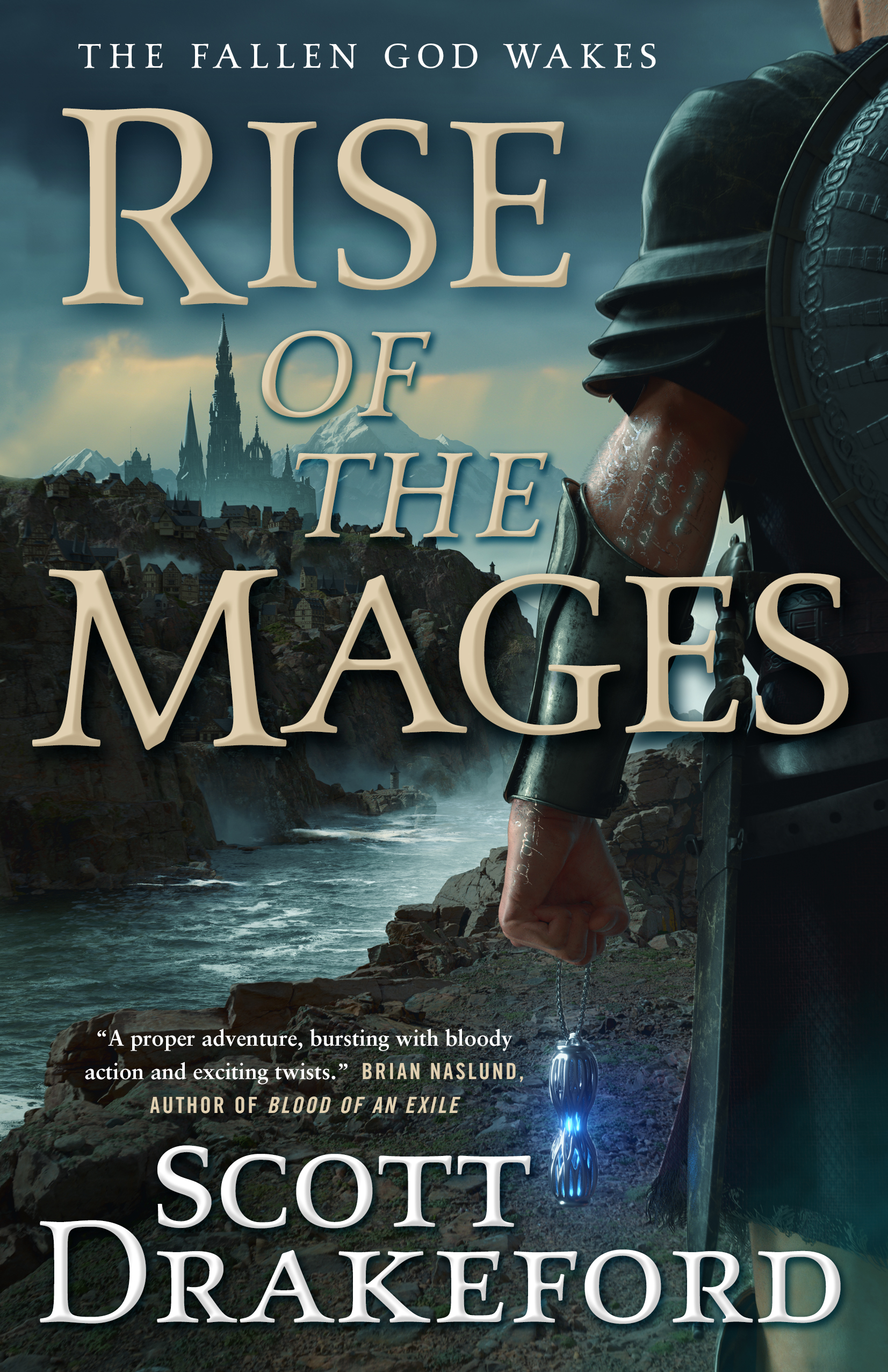

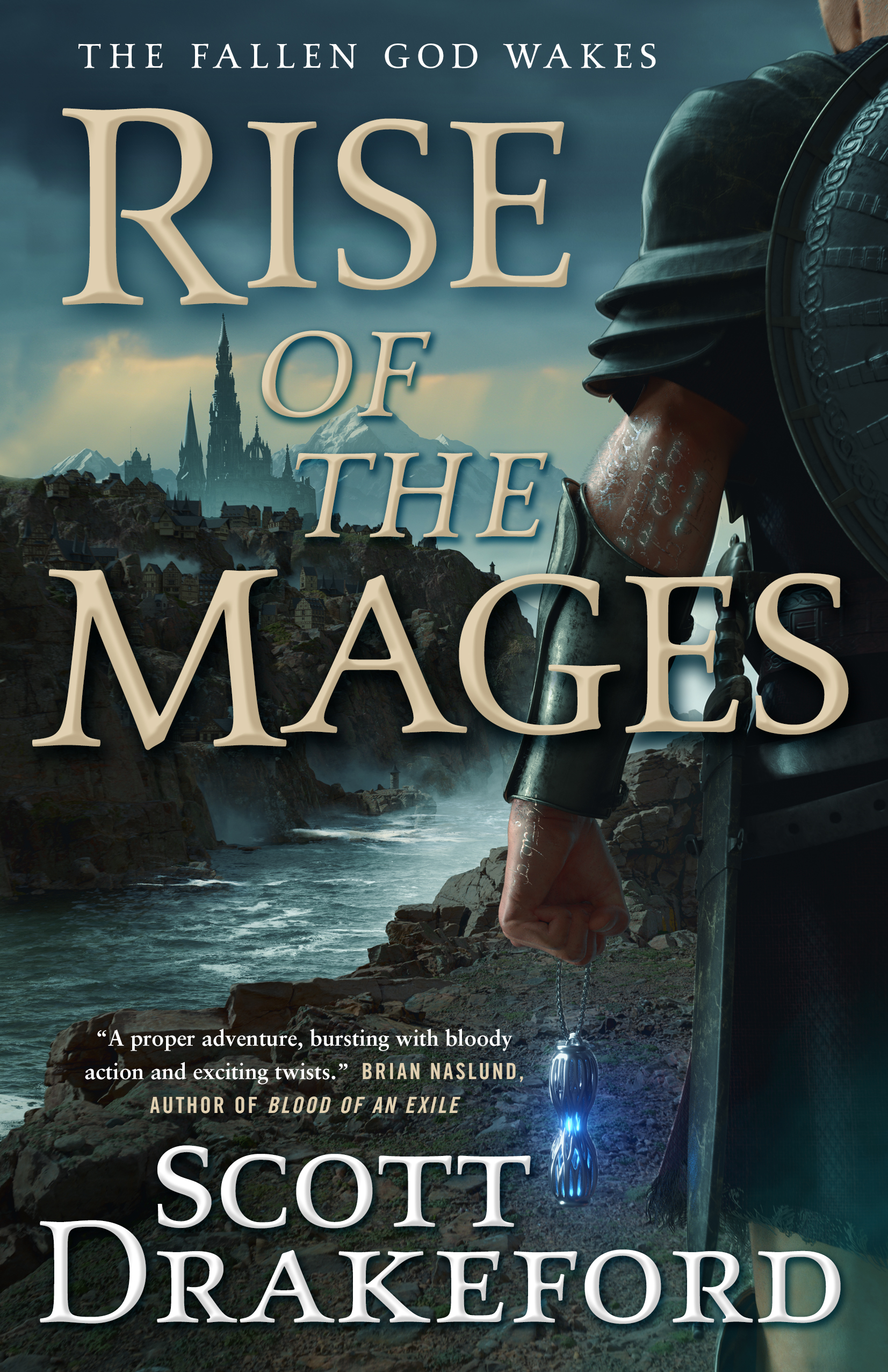

Scott Drakeford’s epic fantasy debut, Rise of the Mages combines gripping, personal vengeance with compelling characters for an action packed first book in a trilogy. Get it in paperback on 1/24/23!

Scott Drakeford’s epic fantasy debut, Rise of the Mages combines gripping, personal vengeance with compelling characters for an action packed first book in a trilogy. Get it in paperback on 1/24/23!

Emrael Ire wants nothing more than to test to be a weapons master. His final exam will be a bloody insurrection, staged by corrupt nobles and priests, that enslaves his brother.

With the aid of his War Master tutor, herself an undercover mage, Emrael discovers his own latent and powerful talents.

To rescue his brother, Emrael must embrace not only his abilities as a warrior but also his place as last of the ancient Mage Kings—for the Fallen God has returned.

And he is hungry.

Please enjoy this excerpt of opens in a new windowRise of the Mages by Scott Drakeford, on sale in paperback 1/24/23.

PROLOGUE

Savian sat at his small desk, in a cramped room, inside the dilapidated stone structure that had been his home—his prison—for five long years. He stared at the night sky through his tiny, woodframed window.

The full moon glowed with a brilliant blue light, partially illuminating the Temple grounds Savian guarded day and night. It had long been his habit to sleep by day in a windowless room in the cellar in order to spend his waking hours enveloped in the peace of the night.

He still didn’t believe that there was anything in this Gloryforsaken corner of the world to guard, but he had no choice but to stay, if he wanted to keep his rank. And his life.

Keeper of the Temple of the Fallen, they had said. No higher honor! None higher, indeed. His lips twisted into a sneer. His long, powerful fingers, callused by years of Crafting wondrous devices only he could conceive, gripped an ivory pen until it cracked under the strain.

Liars. Thieves.

They had used his own ambition to exile him. It had taken him years to see it, but he had eventually realized that he would never fight the Ordenan devils, never rule the Hidden Kingdoms as one of the Seventh Circle, never ascend out of this hell-pit.

So it was that he came to be the Keeper of the Temple, an ancient holy site about as far from civilization as one could get in the Hidden Kingdoms. He was the most powerful outcast in the Malithii Priesthood. His only consolation was the fear he saw in the eyes of the few brethren who visited him.

He ran his hand through his thick black hair and contemplated his own image, reflected in the windowpane. He had been practically a child when he had arrived there, but the strong lines of his face had sharpened, his excess flesh wasted away while guarding the Temple of the Fallen.

Outside, through his reflection in the window, Savian thought he saw a faint flickering light on the side of the Temple, a huge, peaked building, square at the base and triangular on each side.

Probably just moonlight reflected by quartz in the stones, he told himself. I’ll have the slave investigate.

“Kyrit, attend me!” Kyrit was technically his understudy, hoping to raise himself from the Third Circle under Savian’s tutelage. He was Savian’s Mindless now, and the Keeper had no intention of ever releasing Kyrit from the mindbinder he had designed. He felt a twinge of guilt at that but felt much better when he reminded himself that the boy was an irredeemable idiot.

If his brethren ever found out he had Bound one of their own to mindless servitude, there would be trouble. Never mind that Savian’s new Crafting was likely the greatest invention in recorded history. Well enough that few of them visited the Temple, then. None of them even knew this type of binder existed, and Savian planned to keep it that way. Not that any of them would be able to replicate it anyway.

Kyrit appeared at the doorway to Savian’s study, stopping before entering the room to look in hesitantly. His eyes had the cold, lifeless look of those who wore one of the new mindbinders, but with a slight, sharp gleam that implied some retained intelligence. More importantly, it wouldn’t mutate his body into one of the living dead like the ancient soulbinders his brethren coveted. A bit of drool seeped from the corner of Savian’s mouth to fall in his thick black beard as he grinned to himself.

He had set out to re-create the ancient soulbinders—though they had tens of thousands to spare, the secret to making them had been lost to the Priesthood for longer than anyone could remember— but was almost as excited about these that had gone wrong. He suspected that these new binders, mindbinders that sacrificed a certain amount of control for a subject that appeared autonomous, would be incredibly useful. Their like had not been seen for centuries, if they had ever been more than legend—a true work of genius. He would show the Seventh Circle yet. He would repay them their treachery. Soon he’d run the entire Malithii Priesthood—maybe the world— with his mindbinders.

“Kyrit, go take a look outside. Be sure no one has entered the grounds. No dawdling.”

Kyrit ducked his head in a pathetic cringe and plodded toward the door. Savian turned back to staring out the window at the spot on the Temple where he had seen the twinkling light.

Kyrit approached the Temple without the apprehension even Savian felt near the monument to Fallen Glory. The mindbinder did not allow Kyrit to act on the fear he undoubtedly felt. Good.

As Kyrit began to inspect the outside of the building, Savian saw the flash again, stronger this time. An intense blue light outlined the heavy stone slab that had sealed the entrance to the Temple for centuries, perhaps even millennia.

Savian drew in a sharp breath and stared in shock. What could be causing the light inside the Temple? He had heard the claims that the Fallen God of Glory rested here, that the whole reason for the Malithii’s existence was to prepare for his return. He had even used these tales to intimidate and coerce his brethren when convenient. But not until this moment had he truly believed it himself.

He rushed out of his room and into the courtyard that separated his building from the Temple. The pulsing light emanating from the Temple entrance grew stronger as he crossed the courtyard with sweeping strides of his long legs. He could hear a humming, feel a vibration in the ground that reverberated deep in his chest. It was almost as if the Holy Power had taken a life of its own, right there inside the Temple.

Kyrit stood just in front of the entrance to the Temple, staring at the light coming from the cracks around the large stone slab like the imbecile he was.

“Kyrit, come away from there! I’ll have your skin—”

Savian’s furious shout was cut off as the vibration culminated in a blinding pulse of blue light and a deafening blast that blew the stone-slab Temple door outward in a rush of flying chunks of stone.

Savian coughed as he rose unsteadily from where he had been thrown to the ground. Ears ringing, he stumbled across the courtyard toward the now-dark entrance to the Temple. Only a faint glow came from the building now, but the powerful pulsing of raw power continued.

He stepped over Kyrit’s motionless body and crossed the threshold of the Temple, sparing only a brief remorseful thought for his servant as he was drawn to the source of unimaginable power.

He paused just inside the doorway, peering cautiously inside. The interior of the structure appeared to be one enormous room. Vaguely familiar symbols and script on the walls pulsed, illuminating the interior of the Temple intermittently with a deceiving, pale blue light. The air was stale, but surprisingly . . . sterile.

A huge, rectangular enclosure made of stone lay in the exact center of the structure. The stone slab that appeared to have covered it was strewn about the room in chunks of various sizes.

An oversized throne carved from translucent crystal sat at the far side of the large, open room. The throne pulsed with the same rhythmic blue light as the script on the walls, only more intensely. A huge grey stone statue of a bald but otherwise perfect specimen of a man sat on the throne. The statue had more of the same overlapping, angular script inscribed into its surface, almost like the tattoos that covered the Malithii priests. Except that these were glowing and pulsing in tandem with the crystal throne, and seemed somehow more . . . complete, making it impossible to determine a beginning or end to the script.

“So. My children attend me this time.” A rushing tide of a voice swept over Savian; the vibrant power dropped him to one knee. He peered fearfully at the statue. It stared back at him with pale eyes— eyes that shone with life. How could this be? What was this sorcery? He staggered to his feet and drew holy infusori Power from a gold infusori coil in his pocket, prepared to direct it at this charade, to bring down whoever thought to fool him. He would make them pay.

The statue moved, pointed at him. “I prefer you on your knees, loyal one.” There was a hint of amusement in the deep, powerful voice.

As it spoke, furious energy, primal infusori on a scale he could hardly comprehend, tore through Savian, driving him back to his knees.

A sudden realization chilled him to his core, an icicle to the heart. Could the legend be true? He wanted to scream, to run from this place and never look back, but found himself unable to move.

The Being rose from the throne and drew near with heavy steps that reverberated throughout the chamber.

“Rise, child. Tell me your name.”

Savian took a shuddering breath before he rose. He could now see that what he had first thought was a statue of stone was in fact a being of living flesh, flesh an ashen grey color. The script inscribed into its skin still pulsed but changed colors and rhythm slightly as he watched. He could feel infusori energy emanate from the Being to pulse through him in perfect sync with the pulsing of the inscriptions in the Being’s skin.

“My . . . my name is Savian,” he croaked, finally daring to look up to the face of the magnificent Being that towered over him by a foot or more.

The Being regarded him with calm eyes. It reached out, fit its large grey fingers around Savian’s neck, and said, “I have been called many things in this world. God of Glory. Father of All. Fallen One. You shall know me as Master.”

Intense cold shot from the Fallen’s touch around Savian’s neck and through his body. Savian had known the touch of his own experimental binders and had thought it the height of pain and despair. This was worse than anything even his dark mind could have imagined.

As the icy pain reached his heart and brain, however, Savian found his emotions calming. The pain turned to intense pleasure. He looked up to his Master. The ice was power flowing through his veins. The power he had so craved all his life. His Master had made him whole.

Savian knelt on the gritty, dusty floor and proclaimed, “I live to serve, my God.”

The Fallen God of Glory smiled, stalked back to his throne, and sat once more.

“Come, Savian. We have a great work to realize. A Son of Glory has drawn his first breath, one who will taste the white flame and prepares to seize my power as his own. My Sisters ever seek to replace me, but I will prevail as I ever have. But . . . perhaps this time will be different, my Savian. I tire of this pitiful world. We have much to prepare, only short years until our young charge is of age. We will test him, to see what he may yet become.”

The Fallen God’s smile became a deep, mirthless chuckle. “My Sisters will yet lament imprisoning me on this earth.”

0

Emrael Ire and his father Janrael were the first to step from the barge onto Iraean soil. Janrael breathed in deeply, then spat to the side. He flexed his powerful hands as he stopped to survey their surroundings. “Every time I set foot here, I remember my fool father. Too proud to join the United Provinces, too weak to defeat them.”

Emrael had often been told he didn’t look much like his father. His pure white hair—the result of a training accident years ago, and the subsequent healing—was a stark contrast to his father’s dark brown hair and beard. He still felt short standing next to his father, though he was only an inch or two shorter by now, and neither were all that tall. It was his father’s presence that embellished his stature, an aura of command that made him seem the biggest man in the room regardless of physical size.

None would say that Janrael was a small man, however, and Emrael shared his father’s build. Wide, powerful shoulders built through long hours of training with sword and shield; broad backs that had lifted many a supply crate; sturdy legs shaped by long hours of marching with the Legion. They were built to be warriors.

A thrill of excitement coursed through Emrael at finally being allowed to visit his ancestral homeland. He had just seen his twentieth summer, graduated from the Barros Junior Legion, and would be assigned a post soon if he chose to enlist in the Barros Legion right away. He couldn’t contain his eagerness, despite his father’s foul mood. The Iraean countryside looked much like the northern Barrosian countryside, giant pines, oaks, and maples quilted between large swaths of farmland and pasture. Still, it felt different to him. He stepped closer to his father so they were shoulder to shoulder. “I don’t understand why you and Grandmother never returned, after the war ended.”

Janrael chuckled darkly, hand now gripping the rune-carved hilt of his sword, the ancient sword of Ire kings, passed down from father to son for centuries. “We didn’t have many options, son. My mother and her guard fled just before the Corrandes and the armies of the Provinces besieged Ire’s End, and Corrande would have killed our entire family. We’ve had to rebuild our lives from nothing.”

“But you’re the Commander First of the Barros Legion now. Why don’t we go back?”

“The Iraeans that stayed in Iraea don’t like us much either, Em. Many don’t see us as true Iraeans, despite the blood of Mage Kings in our veins, and they’re right. I was born at Ire’s End but raised in Naeran, as you were. The Iraeans would likely throw us to the Watchers or kill us themselves as soon as help us take our ancestral Holding back, never mind handing us a throne. A throne that doesn’t exist anymore, mind.”

Before Emrael could ask more questions, Janrael clapped Emrael on the back. “Let’s go help our men.”

Emrael followed his father back to the barge to help the four squads of fellow Barros Legionmen unload their horses and gear for the campaign. “But you earned your Mark as a Master of War at the Citadel, you could have gone anywhere you wanted and been respected after that. Even Iraea, right? Why do we still fight for Barros?” He said that last quietly, not wanting the other men to hear.

Janrael grimaced, staring at the tattoo of the Citadel’s sword and infusori coil crest on his forearm for a moment, then responded in a grim tone as they led horses from the deck of the ferry. “Many in the Barros Legion are Iraeans like us, who’ve fled the Watchers’ brutality and taxes in our homeland and can’t go back. I’m lucky my mother’s guard joined the Barros Legion and supported us until I was old enough to go to the Citadel, then join myself. I couldn’t leave them behind after what they sacrificed for us. For me. We might have starved, without them. Many did.”

He grunted, facing Emrael to grip his shoulders. “We are Barrosians now, and we dance to Governor Barros’s tune. Just the way it is. Right now, he wants these bandits run out of this stronghold of theirs on the Iraean side of the river. Lord Holder Syrtsan—that’s your friend Halrec’s bastard of an uncle—exiled his own brother to appease Corrande and Sagmyn after the war. He and the Watchers won’t deal with bandits on the river like they’re supposed to, so it’s us.”

His father spat as he hoisted a crate and turned to take it to one of the waiting wagons. “Still don’t understand why he’d send me to see to it personally, though, other than to get me out of the capital so he can turn more of my subcommanders against me while I’m away. He’s regretted allowing the Legion to make me Commander First from the day it happened. Can’t have Corrande thinking he’s giving an Iraean power to lead a rebellion,” he growled with a mirthless chuckle, then spat again.

They arrived at their target after a half-day ride on a dirt road barely wide enough for the small wagons they had brought with them. The bandit stronghold turned out to be a vine-covered castle, most of which was an empty, crumbling shell. Emrael supposed that once, only a generation or so earlier, before the War of Unification, it had likely been home to some Iraean noble and scores of his retainers. Now the roof had caved in and the windows had all been broken out, leaving only the large main hall intact. A wisp of woodsmoke rising from one corner of the structure was the only sign that any living thing inhabited the place.

Janrael, Emrael, and the four squads of Legionmen that had accompanied them waited at the tree line of a ridge above the castle. Emrael’s father shook his head, anguish darkening his eyes.

“These are probably remnants of the Whitehall rebellion. That Norta boy asked me to join he and the Raebren heir, you know. To ‘take my crown and rightful place as a Mage King.’ If not for your mother, I may have been tempted,” he mused. “I may have, but I’m no more a king than I am a mage. Now I hunt them. Such a fickle world.”

A scout on foot made his way through the trees, saluting when he reached them. “Commander First, Sir!”

Janrael nodded. “Captain First Loire. Report.”

“The hills are clear, sir. Only this one set of recent tracks leading to the ruins and another on the other side of the castle. Judging by the traffic, there’s a dozen in there. Two dozen at most.”

Janrael nodded. “Thank you, Captain. Gather your scouts and hold here. Emrael, stay with them.” He raised his voice so the soldiers gathered behind him could hear. “Squads one and two on me, three to the back gate, four on cover.”

Emrael and the small group of scouts waited a few hundred paces away at the tree line as two squads of Legionmen moved into position in front of the main gate, which hung askew but still partially blocked the entrance. They formed up, shields overlapping and swords at the ready. Another squad trotted around the structure to block any escape from the rear service gate. The last squad, crossbows slung across their backs, crouched near a pile of pitch-filled jars and torches a few dozen paces away.

Oddly, there hadn’t been so much as a warning shout as the Legionmen advanced. Emrael watched as his father approached the ruined castle, shield-less, sword still in its scabbard.

“Aho the castle!” his father shouted.

No response.

“If you’re in there, surrender yourselves and you’ll come to no harm.”

Still nothing.

“Last chance! We’ll burn you out if you do not surrender!”

The Commander First shrugged, then gestured to his men nearby.

The waiting squad of Legionmen lit jars of pitch and tossed them over the walls. Smoke soon billowed from several places within the castle, but still no motion from inside. Emrael saw his father’s brow crease in puzzlement.

His father’s confusion turned to shock and dismay as black crossbow quarrels soared from the tree line nearest the front gate, cutting down a large portion of the Barros Legionmen, who were facing the wrong way. A quarrel punched into Janrael’s unprotected thigh. He fell to one knee.

Emrael shouted his surprise and anger, punching the first solider who tried to stop him from running to his father. A second Legionman tackled and pinned him to the ground before he could cross more than a dozen paces of the open ground. Some of the enemy crossbowmen had noticed them, and a few quarrels whistled through the air above Emrael’s head. He watched helplessly as more quarrels flew, lodging in the shields of the few Legionmen who had managed to pull into a defensive circle around Janrael.

Just then, a group of mounted riders burst from behind the ruined gate of the castle. Emrael could see more formed up in the castle’s courtyard behind these, at least fifty of them. They had been ready for this attack, had laid a trap for them. How?

Emrael struggled harder against the men who restrained him as the riders crashed into the Legionmen surrounding his father, hacking with swords and axes, trampling with hooves.

He threw one Legionman to the ground and tried punching the man that held his other arm, but he was grabbed by several of the squad of scouts with him and dragged to the nearby horses. They quickly tied his hands and feet and hoisted him to the back of a horse. Emrael spend the next hour bouncing along on the back of a trotting horse, still bound hand and foot. He was too proud, too shocked to resist further or call out to his fellow Legionmen.

The captain of the scouts called for a halt an hour or so later, apparently judging that they had escaped immediate danger. Emrael, still draped across the back of a horse, stared at the pine needle–strewn dirt beneath his horse’s hooves as the sound of footsteps drew near. He looked up to see Captain Voran Loire staring at him, pity in his eyes, though there was anger in the set of his jaw.

“Are you done sulking, boy?”

Emrael stared at him a moment, then lowered his head. He was embarrassed. Angry. How could they have walked into such an obvious trap? “How did you miss them, Loire?”

“I am Captain First Loire to you, boy. Have you come to your senses?”

“How did you miss them?” Emrael said, nearly shouting now, squirming against the ropes that bound him. “They were ready for us, Voran. How did you miss them? How could you turn tail and run?”

Anger flashed in Captain First Loire’s face, and he stalked back out of view. “So be it. Bounce like a sack of grain all the way back to Naeran.”

Emrael sat in the dining room of his mother’s house inside the Legion compound of Naeran, the capital of Barros. It had been several weeks since they had been attacked in Iraea, and they had yet to find his father. Not even a trace of him.

He pushed away the remnants of a fine meal—beef steaks from the Tallos Holding in the south of the Barros province, cooked over an oak wood fire—and fixed his eyes on his mother, Maira, who sat at the head of the table just to his left. Nearly as tall as he and wellbuilt for a woman, the only sign of her age was the grey beginning to streak her hair. She stared back with red-rimmed eyes.

She broke the heavy silence after a ragged sigh. “What now, my sons? Your father has been missing for weeks; it’s time we thought about relocating. I fear it will not be long before we find ourselves unwelcome in the Legion compound.”

Emrael’s younger brother Ban sat next to him, head down, melancholy and silent. Emrael put a hand on his brother’s bony shoulder and squeezed gently.

Captain First Voran Loire, the same that had brought Emrael forcibly back to the Barros Province after the attack on his father’s expedition, sat at the far end of the long table, having just returned from another search expedition across the river. He spoke in a hushed, gravelly voice. “Aye, you may be right, Lady Ire. The governor has no strong love for Iraeans like us. With Commander Ire gone, you would be wise to make yourselves inconspicuous for a while.”

Emrael pounded his fist on the table. “He isn’t just ‘gone,’ Voran. Those were no ordinary bandits. You and I both know it! Bandits don’t set traps for four squads of Legionmen, and they Fallen well don’t win! Something else is going on, and I intend to find out what. I’ll not give up on Father. His body hasn’t been found; there must be a reason.”

The scout stared at him hard but glanced at Maira and took a deep breath, obviously struggling to be polite. “I’m sorry, son. Your father and his soldiers were lost. We’ve seen none of the missing yet, and it’s been weeks. Like as not, the bastards dumped his body in the river when they realized who they had killed. You’ve been with us on many of the rides; there is no sign of your father. Commander Second Anton is leading an entire battalion across the river as we speak to continue to search for him, but hope is dim. No one can understand why the Commander First led the expedition himself.”

Emrael’s mother murmured softly, “Stubborn fool.”

Emrael shook his head. “He told me that the governor himself asked him to. This doesn’t feel right, Mother. I’m going to help Corlas find Father.”

Emrael’s mother put her hand on his arm. “You may be right, Emrael. I’m afraid that your father’s death may be no coincidence . . . there are many Sentinel priests and their Watcher soldiers in the city. Janrael was not the only prominent Iraean to disappear these past few weeks. This province is no longer safe for us. I have arranged for passage to Ordena and a place for us at the Ordenan ambassador’s residence until the Ordenan cruiser arrives.”

Voran nodded his agreement. “Lady Maira says true,” he said in a gruff, quiet tone. “Many of the officers from Iraean families are already planning to return to Iraea, shame and taxes be damned.”

Maira waved to the other side of the room, where bags were already packed. “I had some things gathered. It should be all we need. Take a few minutes to gather any personal items dear to you, but we leave within the hour.”

Ban lifted his head and stared at Emrael expectantly, eyes red with grief. When Emrael said nothing, Ban slowly stood and walked toward the hallway to their rooms.

Emrael took a deep breath to calm himself. “No. Father could still be out there. I won’t leave him behind and run to Ordena. Besides, this is my home. I can’t just leave.”

Ban stopped in the doorway and looked to Emrael, then to their mother.

Maira sighed. “Emrael, I love your father too, and your intentions are noble. But what can you do? If your father can be found, the men loyal to him—like Captain Loire here—will find him, and we can return straightaway. Look at it as a vacation just until your father turns up.”

Emrael shook his head again, his mind made up. “No, I won’t leave the Provinces while he could still be alive. If the Barros Legion isn’t safe, I’ll go to the Citadel and study there like Father did. They’ll let me in because Father earned his Mark there; he told me so himself. I’ll become the most fearsome warrior the Provinces have ever seen, and I’ll find my father or exact my revenge myself.”

“I’ll come with you,” Ban squeaked.

Emrael started, surprised. Ban usually did whatever their mother asked.

Judging by the look on their mother’s face, she was equally shocked. “You what?” she screeched.

“I’m going with Emrael,” Ban said calmly. “I’m going to study infusori Crafting with Elle. The governor is sending her to join her sister there next year.”

Maira recovered her ability to speak, if not her temper. “That’s preposterous, Banron! The Imperial Academy in Ordena can teach you everything the Citadel can and much, much more. I studied at the Academy myself and can assure you: the Imperators of the Academy far outclass those . . . Crafters and mercenaries at the Citadel.”

Ban shook his head, calmer than anyone in the room. “I’m staying, Mother. I understand if you need to go back to Ordena, but Emrael and I will go to the Citadel. The Provinces are our home, and we can’t leave while there’s still a chance to find Father.”

Emrael crossed the room to put his arms around his little brother, nearly moved to tears. “Thank you,” he murmured to Ban. “We’ll find him someday. We’ll make a grand life for ourselves.”

Copyright © Scott Drakeford 2022

Pre-order Rise of the Mages in Paperback Here:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

By Ariana Carpentieri:

By Ariana Carpentieri:

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/eiffel-tower-paris-france-EIFFEL0217-6ccc3553e98946f18c893018d5b42bde.jpg)

Scott Drakeford’s epic fantasy debut, Rise of the Mages combines gripping, personal vengeance with compelling characters for an action packed first book in a trilogy. Get it in paperback on 1/24/23!

Scott Drakeford’s epic fantasy debut, Rise of the Mages combines gripping, personal vengeance with compelling characters for an action packed first book in a trilogy. Get it in paperback on 1/24/23!

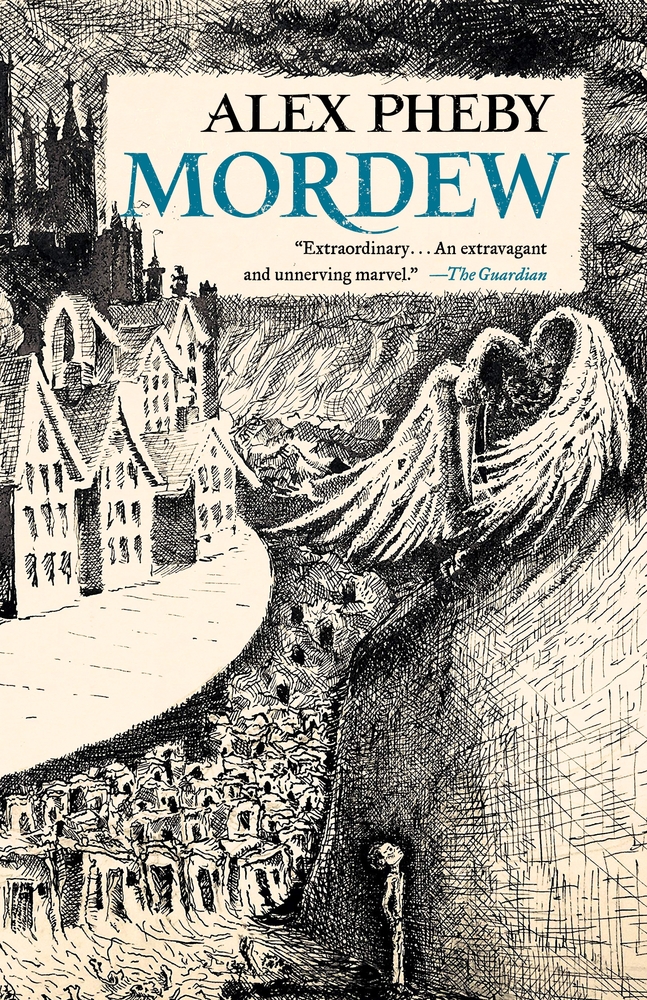

Alex Pheby’s Mordew launches an astonishingly inventive epic fantasy trilogy.

Alex Pheby’s Mordew launches an astonishingly inventive epic fantasy trilogy.