Written by Kathleen O’Neal Gear and W. Michael Gear

Written by Kathleen O’Neal Gear and W. Michael Gear

As archaeologists, we’ve spent over thirty years studying warrior women from a variety of cultures around the world, and, we have to tell you, shieldmaidens pose a problem.

Stories of Viking warrior women are found in a number of historical documents, but several come from factually unreliable heroic sagas, fornaldarsogur. A good example is Hervor’s and Heidrek’s Saga. After the hero, Angantyr, falls in battle his daughter Hervor takes her father’s sword and uses it to avenge his death by killing his enemies. There are similar stories of Brynhilde and Freydis, in Sigurd’s Saga and the Saga of the Greenlanders. But in each case the story is more about myth-making than fact. As well, these are tales of individual women who are highly skilled with swords and fight in battles, but give no evidence for a ‘community’ of women warriors, which the shieldmaidens are supposed to have been.

There are, however, more reliable historical resources. In the 1070s, for example, Adam of Bremen (chronicling the Hamburg-Bremen archdiocese) wrote that a northern region of Sweden near lake Malaren was inhabited by war-like women. But he doesn’t say how many women, nor does he clarify what “war-like” means. Were these women just zealously patriotic, bad-tempered, aggressive, or maybe even too independent for his Medieval Christian tastes? It’s hard to say.

Then we have the splendid references to ‘communities’ of shieldmaidens found in the works of 12th century Danish historian, Saxo Grammaticus, whose writing is sure to make every modern woman livid. Keep in mind, Saxo was likely the secretary of the Archbishop of Lund, and had specific Christian notions about appropriate female behavior. He wrote, “There were once women in Denmark who dressed themselves to look like men and spent almost every minute cultivating soldiers’ skills. …They courted military celebrity so earnestly that you would have guessed they had unsexed themselves. Those especially who had forceful personalities or were tall and elegant embarked on this way of life. As if they were forgetful of their true selves they put toughness before allure, aimed at conflicts instead of kisses, tasted blood, not lips, sought the clash of arms rather than the arm’s embrace, fitted to weapons hands which should have been weaving, desired not the couch but the kill…” (Fisher 1979, p. 212).

Okay. Saxo says there were ‘communities’ of shieldmaidens. Apparently, he means more than one community. How many? Ten? Fifty? Five thousand? In his The Danish History, Books I-IX, he names Alfhild, Sela, and Rusila as shieldmaidens, and also names three she-captains, Wigibiorg, who fell on the field at Bravalla, Hetha, who became queen of Zealand, and Wisna, whose hand was cut off by Starcad at Bravalla. He also writes about Lathgertha and Stikla. So…eight women? They might make up one community, but ‘communities?’

Historical problems like these have caused many scholars conclude that shieldmaidens were little more than a literary motif, perhaps devised to counter the influences of invading Christians and their notions of proper submissive female behavior. There are good arguments for this position (Lewis-Simpson, 2000, pp. 295-304). However, historically most cultures had women warriors, and where there were more than a few women warriors, they formed communities. If the shieldmaidens existed, we should find the evidence in the archaeological record.

For example, do we see them represented in Viking material culture, like artwork? Oh, yes. There are a number of iconographic representations of what may be female warriors. Women carrying spears, swords, shields, and wearing helmets, are found on textiles and brooches, and depicted as metallic figurines, to name a few. One of the most intriguing recent finds is a silver figurine discovered in Harby, Denmark, in 2012. The figurine appears to be a woman holding an upright sword in her right hand and a shield in her left. Now, here’s the problem: These female warrior images may actually be depictions of valkyries, ‘choosers of the slain.’ Norse literature says that the war god, Odin, sent armed valkyries into battle to select the warriors worthy of entering the Hall of the Slain, Valhalla. Therefore, these images might represent real warrior women, but they could also be mythic warrior women.

And where are the burials of Viking warrior women? Are there any?

This is tricky. What would the burial of a shieldmaiden look like? How would archaeologists know if they found one? Well, archaeologists recognize the burials of warriors in two primary ways:

- Bioarchaeology. If you spend your days swinging a sword with your right hand, the bones in that arm are larger, and you probably have arthritis in your shoulder, elbow and wrist. In other words, you have bone pathologies from repetitive stress injuries. At this point in time, we are aware of no Viking female burials that unequivocally document warrior pathologies. But here’s the problem: If a Viking woman spent every morning using an axe to chop wood for her breakfast fire or swinging a scythe to cut her hay field—and we know Viking women did both—the bone pathologies would be very similar to swinging a sword or practicing with her war axe. Are archaeologists simply misidentifying warrior women pathologies? Are we attributing them to household activities because, well, they’re women. Surely they weren’t swinging a war axe. See? The psychological legacy of living in a male dominated culture can have subtle effects, though archaeologists work very hard not to fall prey to such prejudices.

- Artifacts. Sometimes warriors wear uniforms, or are buried with the severed heads of their enemies, but they almost always have weapons: swords, shields, bows, arrows, stilettos, spears, helmets, or mail-coats. A good example is the opens in a new windowKaupang burial.

There are many Viking “female weapons burials,” as archaeologists call them. Let us give you just a few examples. At the Gerdrup site in Denmark the woman was buried with a spear at her feet. This is a really interesting site for another reason: The woman’s grave contains three large boulders, two that rest directly on top of her body, which was an ancient method of keeping souls in graves—but that’s a discussion for another article. In Sweden, three graves of women (at Nennesmo and Klinta) contained arrowheads. The most common weapon included in female weapons burials are axes, like those in the burials at the BB site from Bogovej in Langeland (Denmark), and the cemetery at Marem (Norway). The Kaupang female weapons burials also contained axeheads, as well as spears, and in two instances the burial contained a shield boss.

There are many other examples of female weapons burials. For those interested in the details please take a look at the Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia, Vol. 8, pages 273-340.

In conclusion, did the shieldmaidens exist? When taken as a whole, the literary, historical, and archaeological evidence suggests that there were individual Viking women who cultivated warriors’ skills and, if the sagas can be believed, some achieved great renown in battle. Were there communities of Viking women warriors, as Saxo claims? There may have been, but there just isn’t enough proof to definitively say so…yet.

However, Lagertha, you personally are still on solid ground. You go, girl.

Lewis-Simpson, Shannon. Vinland Revisited. The Norse World at the Turn of the First Millennium. Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador, Inc., 2000: 295-304.

LAGERTHA IMAGE: History Channel

Kathleen O’Neal Gear & W. Michael Gear are Anthropologists and award winning authors who have authored and co-authored over 40 books. Their next book, opens in a new windowPeople of the Songtrail, releases on May 26th.

Follow the Gears on Twitter at opens in a new window@GearBooks, on opens in a new windowFacebook, or opens in a new windowvisit them online.

People of the Songtrail by Kathleen O’Neal Gear and W. Michael Gear

People of the Songtrail by Kathleen O’Neal Gear and W. Michael Gear opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

The Monster Baru Cormorant by Seth Dickinson

The Monster Baru Cormorant by Seth Dickinson opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Bowl of Heaven by Gregory Benford and Larry Niven

Bowl of Heaven by Gregory Benford and Larry Niven opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

The Impossible Contract by K. A. Doore

The Impossible Contract by K. A. Doore opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

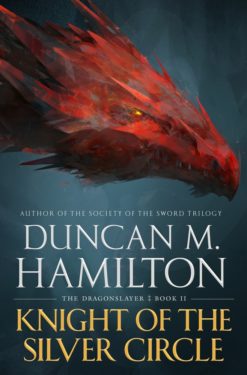

Knight of the Silver Circle by Duncan M. Hamilton

Knight of the Silver Circle by Duncan M. Hamilton opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window