Chapter 2

When Josette next woke, the air was filled with the mingled odors of blood, putrescence, and the unnerving sweetness of gangrene. She opened her eyes and flinched at the intensity of the morning sun shining through a dirty window.

Her hand rose to shield her eyes, brushing the bandages over her forehead. Pressing on them, she could feel a dull ache just above the hairline on the left side. The area was numb in the middle, and she worried that she’d been trepanned.

She was nearly certain she hadn’t, but it probably didn’t matter in any case. No officer, to Josette’s knowledge, had ever been dismissed from the army for having brain damage. Indeed, she knew several gentlemen for whom it seemed to be an advantage.

She sat up and looked around the room, idly picking flecks of blood from her matted brown hair. It was a narrow room, large enough for only two cots. In the other cot lay a patient wrapped head to foot in bandages. Burned, no doubt. Josette knew that it must be a woman, but only because the army wouldn’t put her in a room with a man—even a dying one. They might cheerfully send men and women alike into the jaws of death, to be shot, bayoneted, and torn to pieces by cannonballs, but they would never violate propriety.

A stone bottle sat on the table next to the burned woman’s cot. It tempted Josette, for there was no water by her cot, and she’d had nothing to drink since before the battle. And after all, the woman wouldn’t be wanting it. She would soon want nothing at all, judging by her thin and ever-shortening breaths.

Josette decided, in the end, that she would not steal water from the dying woman. If nothing else, it would be a hard thing to explain to the orderlies.

She stepped out of the room and into the dim hospital corridor, where the smell of decay was even more oppressive. Across the hall, a door opened into a ward crammed with wounded men. The corridor was almost as crowded, with cots lining both walls. But there were more men than cots—so many that men were stretched out on the floor or propped against the wall as their wounds dictated.

She recognized one of them. He was a wiry, graying, weather-beaten man of about fifty, sleeping with his chin against his chest outside her door. It was Sergeant Jutes, chief of the Osprey. His legs were splayed, with the left one bandaged and resting under a cot, where it was less apt to be stepped on. He looked pale—paler than usual, even—and she had to watch for the rise and fall of his chest to be sure he was only sleeping.

“Sergeant,” she said, the words rising as a croak from her parched throat.

Jutes’s head whipped up and his eyes shot open. “Sir,” he said, crisp and clear. He was halfway into a salute when he froze, his light gray eyes going wide at the sight of Josette.

Oh no. Had she walked into the corridor half-naked, in one of those flimsy hospital gowns? She looked down and was relieved to find herself still in uniform, save that her bloodstained pea jacket was missing both rows of brass buttons, in addition to the other damage inflicted upon it by her rescuers. Perhaps it was only the copious amount of dried blood, then, which alarmed Sergeant Jutes.

“Not to fear,” she said. “Only a small portion is mine. I wish I could remember who the rest belongs to, but I don’t imagine they’re in a position to ask for it back.”

Jutes was pulling himself to his feet in such a hurry that he nearly overturned the nearest cot.

“For God’s sake, man. You don’t have to get up.” But it was too late for that. Josette knelt down and helped him the rest of the way.

Standing upright, Jutes completed his salute, touching knuckle to forelock in the older fashion. Sergeant Jutes wasn’t tall, but he stood a full head taller than the diminutive Josette. “Wasn’t sure you’d make it, sir,” he said. His eyes flitted to Josette’s forehead.

“I’ve had worse,” she said, feeling the wound. “I’m doing a hell of a lot better than my roommate.”

“That’s Auxiliary Ensign Naylor, sir.”

“From the Mallard?” Josette looked back into the room, aghast. “Good God. And I was about to steal her water.” She turned back to him. “How’s your leg?”

“Hain’t turned putrid yet,” Jutes said, in a tone that mingled gratitude and hope.

“Hurt it in the crash?”

Jutes looked at her in surprise. “Sir?” he asked.

“Did you gash your leg when we went down?”

“No, sir,” he said, and was silent for a moment. “I caught a bayonet pulling you out of the wreckage. Sorry I couldn’t stay with you after that, sir.”

“Good God,” she said. She’d never been any good at thanking people, especially those subordinate to her, and this was the first time anyone had saved her life. Overwhelmed, she could only pat him on the shoulder and say, “Well, it’s damn bad luck about the leg. Where’s Captain Tobel?”

Jutes hesitated. “Sir?” he asked.

“Captain Tobel. I thought I recalled that he was wounded.”

Jutes stammered out, “No, sir. I mean . . . he’s dead, sir.”

Her gasp turned half the heads in the corridor. She simply couldn’t imagine a world in which Captain Tobel was one of the bodies rotting on that hill. “Good God, is anyone but us alive?”

“Sadiq and Ancel were killed by skirmisher fire, along with the cap’n, before we landed. Borden lost both legs in the crash and may live yet, and Rouget caught a bullet in the chest going over the rail. Talbot, Ferat, and Jobert died in the melee on the hill, and the Guilbert brothers lost an arm, an ear, and a dozen teeth between them.”

That was half the crew—half the men she’d worked with every day for the past two years. She caught herself wondering how Captain Tobel had allowed such a massacre to happen, before she remembered that he had been the first to go. When he fell, she had taken command. She wasn’t supposed to take command. Auxiliary lieutenants such as Josette were not permitted to take command of an airship. Indeed, the auxiliary officer ranks had been created to accommodate the peculiarity of female air officers, who had to be protected from the burden of command—particularly in battle, when a single moment of womanly hysteria might result in disaster.

Or so they’d explained to Josette, back when they made her an auxiliary ensign. Now she was an auxiliary lieutenant, a rank which permitted her to be the second-in-command of any airship bearing a crew of up to thirty souls, and even to stand night and morning watches if the weather was especially mild. But it did not entitle her to take command of a ship in battle, no matter the circumstances.

But she’d taken command anyway. She’d taken command, and half the crew had lain dead or mangled within a quarter of an hour.

“And Ensign Sandali stayed aboard to fire the ship,” Jutes said. “It went alight something beautiful, but the poor lad never came out. Everyone else is alive and well. That’s thanks to you, sir, and I’d venture somewhere north of two thousand fusiliers owe you their lives, too.”

Jutes’s last comment hardly had room to register inside her mind. It took everything she had to keep from weeping in front of her sergeant—or rather, the man who had been her sergeant until she crashed her airship.

“You all right, sir? It was a high butcher’s bill, to be sure, but it needed doing. There ain’t many who could have pulled it off as well.”

Through the mental fog, she noticed that the squawking chatter of the packed corridor had abated, to be replaced by infectious whispering. Somewhere on the edge of earshot, she heard someone say, “That’s her.”

“Nah it ain’t,” another voice replied. “She’s taller. Over six feet, I heard.”

She looked at Sergeant Jutes. “Perhaps we should continue this conversation elsewhere.”

Jutes said, “I ain’t allowed in the officers’ rooms, sir.”

Josette found that she could not endure the stares of the men in the hall, nor the thought of returning to her room alone to count the seconds between Ensign Naylor’s labored breaths. “Then what do you say to getting the hell out of this hospital?” she asked.

Jutes looked relieved. “Been tryin’ to since they sewed me up, sir, but I can’t outrun the damn nurses on this leg.”

She nodded. “Good. Any other surviving Ospreys in here?” By which she meant other crew members from the late airship.

“No, sir. Apart from us and Private Borden, they’ve all been given to other ships.”

“Then we’ll just have to do it ourselves.” She supported him with one of her arms under his. “Put your hand on my shoulder there, and I’ll help you walk.”

Jutes looked like he might jump out of his skin from the sheer impropriety of it. “Begging your pardon, sir, but I ain’t sure it’s proper for an officer to be holding up a sergeant like this.”

Josette began to move, forcing him to walk along with her or else be pushed over. “Don’t be an ass, Jutes.”

“Yes, sir,” he said, and hobbled down the corridor at her side.

The soldiers in the corridor parted at their approach, stepping or crawling out of the way to leave a space so wide that Josette and Jutes had a foot of clearance on either side. The whole spectacle made her cringe.

A pair of nurses came down the corridor, obviously aiming to intercept the escapees, but when they saw Josette, they moved aside so quickly that one of them stepped on a man’s hand in her haste to get out of the way.

The fleeing patients passed another ward, where the casualties were worse than those in the hall. Some of the men there were already dead and had been so for hours, left to stiffen in their dying contortions by a hospital staff too busy to remove them.

Josette saw the entryway ahead. The front door opened and a corporal pushed his way inside. He shouted down the hall, “Another trainload of wounded is coming in.”

A wrinkled nurse stuck her head out of the nearest ward and shouted back, “No more room! Put them in the street!”

Josette whispered, “We did win the battle, didn’t we, Jutes?”

“Yes, sir,” he said firmly. “It was a stunning victory.”

Josette ran her eyes over the dead and wounded, packed shoulder to shoulder in the wards. “God help the enemy,” she said.

Lord Bernat Manatio Jebrit Aoue Hinkal, son of His Lord the Marquis of Copia Lugon, woke shortly before noon. This was rather earlier than was his fashion, but the snoring of his bedmate made it impossible to sleep any later. The bedmate was a matronly woman of at least fifty, which made her twice his age, but this thought caused him no shame, for he valued maturity in his lovers.

Bernat rose to stand, tall, thin, and quite naked in what little sunlight made it through his hotel room’s soot-encrusted windows. He stepped to the washbasin, scraped away the night’s growth of whiskers, and brushed his short, midnight-black hair. He donned the accouterments of nobility, putting on silk stockings, a fine pair of breeches, a ruffle-sleeved shirt, and a rose-colored sherwani. He applied a layer of powder to his cheeks and a dab of lightener under his brown eyes. He contemplated his wig for a moment, but decided against it. The damn thing was itchy, and he wasn’t planning on visiting anyone important.

On his way out, he kissed the woman who lay snoring in his bed, and left his last gold lira on the pillow next to her. Outside, the smoke was oppressive. It drifted in from the manufactories east of Arle and shrouded the entire city in gloom. Even worse, it clung to everything, covering the inn’s expensive mahogany siding with a layer of soot.

The noonday street was clogged with carriages and carts, all going in the same direction. Bernat looked for the nicest covered carriage and hailed it.

“Sorry, my lord!” the coachman called back. “I’m hired.”

Only then did Bernat notice the men lying in and atop the carriage. Indeed, there were men in all the carriages. There were even men in the carts. “What’s going on?” he asked.

“Casualties from the battle,” the coachman said. “They’re comin’ in by the trainload. Ain’t a coach to be had, I’m afraid. Army’s hired ’em all.”

“Then how am I supposed to get to the semaphore office?”

The slow progress of traffic was taking the coachman out of earshot. He raised his voice and said, “It’s only a few blocks that way, my lord. You might resort to walkin’.”

Bernat set off in the indicated direction, but not before giving an indignant snort. Three blocks later, his shoes covered in mud, he arrived at the semaphore station. It was quite a large office, and bustling with clerks. The one nearest the door stood hunched over his desk, scribbling on a slip of paper. Without looking up, he said, “Be with you in just a moment, my lord. The battle’s got us a bit busy handling dispatches for the army.”

Bernat sighed. “Why even have battles when they’re such a vile inconvenience to everyone?”

“Words of wisdom, my lord, words of wisdom.”

“I mean, don’t get me wrong,” he said, though the clerk gave only a cursory impression of listening. “I’m not one of those silly pacifists who seem to be popping up everywhere. I only mean that if we’re fighting a war over Quah, they ought to hold the battles there, oughtn’t they? It’s only fair. It wouldn’t even be such a terrible burden for Quahnics, for they must certainly be used to this sort of thing by now.”

“Only fair, my lord.” The clerk finished writing and looked up at Bernat. “And what can I do for you?”

He was sure now that the man hadn’t been paying attention, but it didn’t matter. It wasn’t so important that the common people listened—only that they agreed. “I must send a message to Lady Hinkal, staying in the palace at Kuchin. It’s very important.”

The clerk licked his finger and pulled a fresh slip from his drawer. “Arle to Kuchin costs twelve dinars per letter,” he said.

“That much?”

“Sorry for that, sir, but it is one of our busiest lines, and the cost of materials for semaphore towers being what they are these days . . . and, by God, if you saw the wages the signal operators are demanding, citing the current labor shortage, as if that excuses . . .” The man seemed suddenly to remember himself. “Sorry, my lord. What would you like the message to say?”

Bernat looked into his purse and gave it a shake. A few small coins jangled against each other. “Better keep it short,” he said. “Just make the message, ‘Mother, send money.’”

The clerk jotted it down and counted the letters. “That’s nine silver rials so far,” he said. “And how would you like to sign the message, my lord?”

Bernat looked into his purse again and frowned. “Just leave it unsigned,” he said. “She’ll know who it’s from.”

Once Bernat had handed over most of the money in his purse, the clerk stamped the slip and said, “It’ll probably be afternoon before it’s sent, and tomorrow at the earliest before you can get a reply. There’s a huge backlog, and the horse couriers are having a hard time getting through the streets.”

Bernat pointed at the ceiling. “Horse couriers? But there’s a semaphore tower on top of this building. It can’t be only for show. I saw it signaling yesterday.”

“Yes, my lord, but the smoke’s too thick today to get a message through, so we have to send a rider to the tower outside town.”

Bernat sighed and said, “This is the most horrid day ever.”

“What do you mean, no billets are available?”

The quartermaster looked at Josette and Jutes as if they were stupid. She was a stocky auxiliary lieutenant, sitting behind a desk piled high with ledger books and stacks of paper.

“I mean,” said the quartermaster, “that I cannot provide you with billets, because there are none available.”

Josette had once expected fellow auxiliary officers to treat her better than her male comrades, but experience had long since taught her differently. “Lieutenant Bowden,” she said, for this was not her first battle with the Royal Aerial Signal Corps’s quartermaster’s office, and she knew most of her enemies by name. “We passed empty barracks on our way in.”

“Which are reserved for all the convalescents we’re expecting. You may not have noticed, but there’s been a battle.”

Josette pointed to Jutes, who was propped up in the doorway. “You may not have noticed, but we were in the middle of the damn thing. Granted, we only played a small part, being bayoneted and bludgeoned on the front lines, while you were back here, fighting with a ferocious quill for God, Garnia, and bureaucracy.”

The quartermaster looked up at Josette’s bloody uniform, then back down at her paperwork. After sorting a few pages into their proper piles, she said, “If we provided quarters for every bugger who escaped from the hospital, we’d have none left.”

Josette leaned over the desk. “Indeed, because they’d be filled with airmen. One might even argue that this is the sole function of airmen’s quarters: to be filled with airmen, however much that state of affairs may inconvenience you. As we are airmen, and as we are convalescents, we require quarters.”

This time, the quartermaster didn’t even look up from her work. She only thumped a ledger and said, “That ain’t what it says here.”

Josette stood where she was for several seconds, trying to formulate a plan of attack. None occurred to her, so she turned and walked out of the quartermaster’s office, defeated again. Outside, she stopped to plan her next move. As she pondered, she heard the whine of an airship’s steamjack out on the airfield. She could barely see the ship’s silhouette through the smoke blowing in from the city, but it sounded like Captain Emery’s chasseur, the Ibis.

Jutes cleared his throat, interrupting her train of thought. “Sir,” he said, “if I may have your leave, I’ll be heading back to the barracks now.”

She arched an eyebrow. “I thought I was the one with the head wound,” she said. “There aren’t any quarters for us.”

“No, sir,” he said. “But I’ll be bedding down anyway. If anyone comes along, saying they’ve been assigned to my bunk, I’ll tell ’em there’s some mistake and send ’em to the next one. Ain’t exactly my place to say, sir, but if I was you, I’d do the same thing.”

“And what happens when there are no spots left, and they figure out what you’ve done?”

Jutes shrugged. “Begging your pardon, sir, but in this army it’ll take weeks for them to figure that out, and by then we’ll probably be assigned to another ship anyway.”

He saluted and turned toward the barracks. The officers’ quarters were in the same direction, so she helped him along. On their way, they saw the Ibis’s enormous, cigar-shaped envelope loom out of the smoke overhead, on its way west. Ibis was low enough that Josette could hear the bustle of half a dozen crewmen running about on her crowded hurricane deck, which was the wide wicker gondola hanging under the ship, a third of the way back from the nose.

Josette cupped her hands around her mouth and, at a surprising volume for her small frame, shouted out, “Ibis! Fair winds!”

Captain Emery’s head appeared over the railing. He shouted back, “Dupre! Congratulations on your victory!” Ibis was already passing out of earshot. Emery waved and then returned to his station.

Josette frowned. “Was he mocking me?”

Jutes looked surprised. “Sure he wasn’t, sir.”

Josette mulled it over for a few paces. She’d served with Emery several times. They’d even graduated in the same class at the Royal Aeronautical Academy, back when women had to pass themselves off as men to get in. He had never said a word to give her away, though he could have done, nor had she ever known him to resort to mockery. “But he wished me congratulations on my victory. Congratulations for what?”

“The word around the army, sir—which I will surely back up, seeing as how I was there—is, it was your doing that turned the battle,” Jutes said. “General Lord Fieren was shy to attack the Vins, what with them holding that rocky hill. Overlooked the path of our advance, see, and it would’ve been hell on the ranks, with all that rifle fire coming down from it. I been in the infantry, sir, and I can tell you he was right about that, at least. Anyway, he tried scraping those Vin skirmishers off with artillery, and by sending our own skirmishers up the slope, but the damn Vins had nice cover up there and wouldn’t budge, so he resorted to sending Osprey in to clear them out.”

Josette sighed. “But we didn’t clear them out, Jutes. I crashed the damn ship.”

“Not crashed, sir. A hard landing, to be sure, but not a crash. Or, if it were a crash, you crashed her prettier than I ever seen. Brought her down like a barrel o’ bloody bricks, right on the heads of them Vin skirmishers. Bloody Vins didn’t know what bloody hit ’em. All they knowed is all of a sudden they was underneath half an acre of canvas.”

It had been a damn fine piece of work, now that she thought of it. A crashed airship, unless all its bags of buoyant luftgas were completely obliterated, didn’t want to come down in one place. It wanted to be blown by the wind, bobbing along the ground at unpredictable intervals. But she’d wedged Osprey’s tail into the rocks, so that it had pivoted down to land atop the skirmishers. To them, it must have looked like the sky was falling.

“And it stirred those skirmishers up real nice,” Jutes said, grinning wide. “And we made a damn fine account of ourselves, if I may say so, sir, being less than twenty airmen against a hundred hard soldiers. Don’t know how long we could have kept it up—prob’ly not long—but we kept ’em busy long enough for our men to get up the hill in force.”

She scratched around the edge of her bandages. “And so what if that’s true? I wasn’t even awake for most of it.”

Jutes shrugged. “Not for the last part, sir. But you was still the cap’n, even then. I hear the newspapers are all calling it ‘Dupre’s miracle.’ Saw one paper saying—now how was it they put it?—‘Auxiliary Lieutenant Dupre accomplished, by pluck and daring, what all General Lord Fieren’s fancy stratagems and tactics could not.’”

She didn’t like the sound of that. Not at all. It meant trouble. “And they’re saying all this because I crashed my ship and set fire to it?”

Jutes nodded eagerly.

And now she finally understood what was going on, and that things were even worse than she’d thought, for she’d been sold out by the goddamn newspapers. Some of the news sheets were pro-government, while others were more critical, but every last one of them loathed General Lord Fieren, the architect of the army’s campaign in Quah. Or rather, the architect of the army’s dismal fighting retreat across Quah, a territory which had been taken from the Vins at the cost of so much Garnian blood only a decade earlier. Since then, Garnia had defended it against multiple attempts to retake it by the Vins, against opportunistic attacks from Brandheim, and even against Quahnic revolt, and Garnia had won every time.

But even in victory the army was beginning to wear thin, and this war wasn’t going quite as well as the ones before. Shortages of equipment, experienced officers, and men fit to hold a musket had all conspired to make it much less fun to read about in the newspapers—or so she’d gathered.

In fact, the battle that brought Fieren south to Arle had been his first outright victory against the Vins since the latest war began, and would surely prove a great morale boost for the army and the country at large. Faced with such a victory, it should have been impossible for the papers to condemn Fieren, but they’d managed to do it by giving Josette all the credit. All of which meant that her career would be quietly demolished if the public ever lost interest in her.

Judging by their past infatuations with war heroes, she’d be lucky if she had a week.

In a tropical country where shadowy political affairs lurk behind the scenes of its glamorous film industry, three people maneuver inside a high stakes game of statecraft and espionage: Lillian, a reluctant diplomat serving a fascist nation, Aristide, an expatriate film director running from lost love and a criminal past, and Cordelia, a former cabaret stripper turned legendary revolutionary.

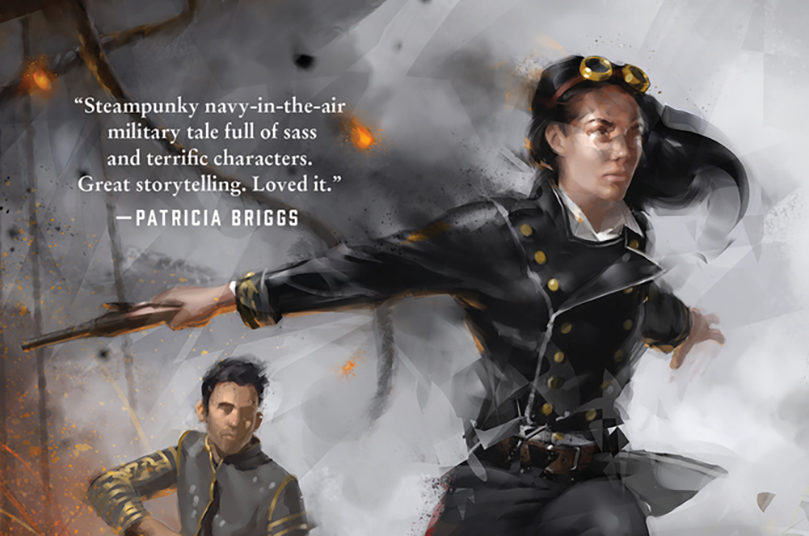

In a tropical country where shadowy political affairs lurk behind the scenes of its glamorous film industry, three people maneuver inside a high stakes game of statecraft and espionage: Lillian, a reluctant diplomat serving a fascist nation, Aristide, an expatriate film director running from lost love and a criminal past, and Cordelia, a former cabaret stripper turned legendary revolutionary. “All’s fair in love and war,” according to airship captain Josette Dupre, until her hometown of Durum becomes occupied by the enemy and her mother a prisoner of war. Then it becomes, “Nothing’s fair except bombing those Vins to high hell.”

“All’s fair in love and war,” according to airship captain Josette Dupre, until her hometown of Durum becomes occupied by the enemy and her mother a prisoner of war. Then it becomes, “Nothing’s fair except bombing those Vins to high hell.” Ravaged by barbarian Scálda forces, the last hope for Eirlandia lies with the island’s warring tribes. Wrongly cast out of his tribe, Conor, the first-born son of the Celtic king, embarks on a dangerous mission to prove his innocence.

Ravaged by barbarian Scálda forces, the last hope for Eirlandia lies with the island’s warring tribes. Wrongly cast out of his tribe, Conor, the first-born son of the Celtic king, embarks on a dangerous mission to prove his innocence. It’s 1814. Napoleon has escaped his imprisonment on Elba. Britain is at war on four fronts. And at Stranje House, a School for Unusual Girls, five young ladies are secretly being trained for a world of spies, diplomacy, and war….

It’s 1814. Napoleon has escaped his imprisonment on Elba. Britain is at war on four fronts. And at Stranje House, a School for Unusual Girls, five young ladies are secretly being trained for a world of spies, diplomacy, and war….