opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

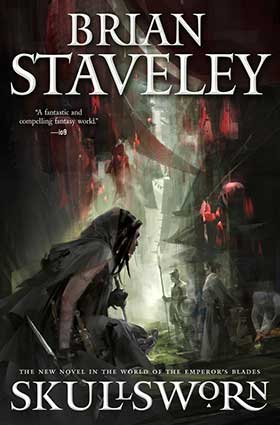

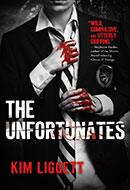

Pyrre Lakatur is not, to her mind, an assassin, not a murderer—she is a priestess. At least, she will be once she passes her final trial.

The problem isn’t the killing. The problem, rather, is love. For to complete her trial, Pyrre has ten days to kill the seven people enumerated in an ancient song, including “the one who made your mind and body sing with love / who will not come again.”

Pyrre isn’t sure she’s ever been in love. And if she fails to find someone who can draw such passion from her, or fails to kill that someone, her order will give her to their god, the God of Death. Pyrre’s not afraid to die, but she hates to fail, and so, as her trial is set to begin, she returns to the city of her birth in the hope of finding love . . . and ending it on the edge of her sword.

opens in a new windowSkullsworn will be available on April 25th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

1

The creatures of the Shirvian delta are fluent in the language of my lord. Even the smallest have not been made meek. A millipede coiled around a reed can kill a woman with a bite. So can the eye-spider, which is the size of my fingernail. Schools of steel-jawed qirna ply the channels, each fish more tooth than tail; I’ve watched people toss goats to them—an old offering to forbidden gods; it is like watching the animal dissolve into blood and froth. There are crocs in the delta half as old as the Annurian occupation, twenty-five-foot monsters that have lurked in the rushes for a hundred years or more, the most deadly with names passed down from generation to generation: Sweet Kim, Dancer, the Pet. The only thing in the delta that can kill a croc is a jaguar, a fact that might offer some solace if that great cat, too, didn’t feast on human flesh. There are ways to avoid crocs and qirna. Jaguars, though—it’s hopeless. Like trying to hide from a shadow.

Ananshael’s first servants were the beasts. Long before we came, blood-hungry carnivores stalked the earth, each claw and tooth, every twisted sinew a living tool fashioned to the same absolute end. Before the first note of the first human song, there was music: a howl launched from some hungry throat, the rhythm of paws quick through the brush, over the hard-packed dirt, a bright, final squeal, then the silence without which all sound means nothing. The devotion of beasts is crude and unchosen but utterly undiluted.

A fact of which I was reminded when the causeway over the delta, the causeway upon which we’d been walking for the better part of twenty miles, a causeway that had been safely suspended on wooden pilings fifteen feet above the rushes, groaned with a strong gust of wind. Until that moment, the day had been still as a painting, the bridge like bedrock beneath all the thousands of feet. When it shifted, the people around us—travelers and muleteers, tinkers and wagon drivers—glanced uneasily down at the swirling currents. A worried mutter sprang up like new fungus after a rain. Some people stopped in their tracks. Others moved faster, hurried unknowingly into Ananshael’s waiting arms.

“Does it always do that?” Ela asked, turning to me. She didn’t look concerned. During the whole thousand-mile trek from Rassambur, she had not once looked concerned. Although we’d been marching down the causeway since dawn, she looked like a lady out for a summer stroll in her light sandals and bright silk ki-pan, a parasol of waxed red paper tossed idly over her shoulder to keep the sun off. During the first days of our trip, her packing had struck me as impractical. Soon enough, however, I’d come to envy her sartorial choices—on hot days, those short dresses looked enviably cool; when storms came, the parasol kept her head and torso dry while the rain ran harmlessly down her long legs and off the sandals.

“I don’t remember,” I confessed. “It’s been more than fifteen years since I was here.”

The wind gusted again, raking the rushes, making the great, tar-soaked posts of the causeway creak. Beneath my feet, the wood shuddered.

Kossal ignored it, just kept stomping along in his bare feet and gray robe exactly as he had every day since Rassambur, indifferent to rain or hail, washed-out sections of roadway, or even the immensity of the Shirvian delta spread silently beneath and before us as far as the eye could see.

“These people,” Ela said, waggling a finger at the crowd around us, “look nervous.”

She was right. A few paces in front of us, a basket-packer bent almost double beneath his load had quickened his pace, muttering something that sounded like a prayer. Beyond him, a woman was urging her husband to walk faster, pointing vaguely toward the east, where hot white clouds scraped over the sky. I felt my own pulse quicken, which was strange.

I’d made peace, during the long years in Rassambur, with my own impermanence. My god’s mercy and his justice didn’t frighten me. I had learned to face the prospect of my own unmaking with peace, even with joy. At least, I thought I had. I discovered, standing on that pitching, swaying causeway, that coming back to the place where I was born had rekindled something inside me, some childhood instinct deeper than any epiphany. My mind might have been calm as the people around us mounted panic’s swaying ladder, but my body knew we had come back, my bones and blood recognized the thick reek of mud, the hot salt air.

“I will confess,” Ela went on, “that I will be vexed if this marvel of Annurian engineering suddenly becomes less marvelous.”

Kossal shrugged. “We live until we die.”

“And yet,” Ela added speculatively, “the best beds and finest plum wine in Dombâng wait at the end of this causeway. It would be a shame to miss out.”

“You do understand,” the old priest replied, glancing over, “that Rassambur’s coin is not for the spending on frivolities and idle luxury.”

“Life is an idle luxury, Kossal. Before I go to the god, I intend to enjoy wine and a soft bed at every available opportunity, hopefully in the company of someone very beautiful and very naked.”

Then, before he could respond, as though in rebuke to Ela’s hopes, the wind kicked up again, and the world lurched. Women and men hoisted their screams into the air, ten dozen bright pennons flapping madly above us as the quarter-mile span on which we stood twisted, shrieked, broke away from the causeway at either end, listed toward the west, and then, with a snapping of old wood, collapsed.

It was a soft landing—all water or mud—which somewhere else might have been a comfort. Not here. When the fishers of Dombâng who ply the delta channels talk about someone who has died—died in any way, alone in bed, at the tavern, stabbed in some back alley—they always use the same expression: he flipped the boat. To be boatless in the waters of the delta, the wisdom goes, is to be dead.

Of course the wisdom isn’t quite right. Funny how often that happens. The Vuo Ton live in the delta somehow, well beyond the boundaries of Dombâng. Occasionally, someone from the city itself survives. I remember Chua Two-Net walking out of the delta, bleeding but alive. It doesn’t happen very often.

All of which might suggest that the Shirvian delta would be a terrible place to build a city, but that, after all, was the point. According to the stories, Dombâng’s first settlers—the women and men who arrived among the house-high reeds thousands of years earlier—didn’t come for the fishing or the sunsets; they came to hide. Harried by the Csestriim near the end of those ancient wars, they fled into the rushes. The Csestriim—some of whom had lived five thousand years and more—died trying to follow. It could have been the snakes or crocs that killed them, the qirna or the spear rushes, but those earliest settlers told a different tale, one of gods built like humans but faster and stronger, impossibly beautiful. It was these, the story goes, that killed the Csestriim, and so it was to these that the human survivors, eking out their tenuous survival deep in the delta, began to offer sacrifice. For thousands of years something seemed to guard the people of Dombâng, shielding them as the hamlet grew to a village, the village to a city, something in the delta promising death and protection both.

Then the Annurians came.

When the empire invaded, it did so with its typical mixture of breathtaking vision and plodding determination. Instead of trying to thread the hidden path through the delta’s hundred thousand deadly channels, the Annurian legions arrived on the north bank of the delta, established their camp, and started building.

A million trees were felled to build the causeway, some hauled from a hundred miles off. Ten thousand soldiers died—some taken by disease, some bitten by snakes or crocodiles, some devoured by schools of qirna, some simply . . . gone, lost in the shifting labyrinth of reeds and rushes. Not for nothing did the people of Dombâng believe that the gods of the delta would protect them once again. To the city’s horror, however, the Annurians accepted their losses and simply kept on building. When the Annurian commander was told the causeway would be the largest structure in the world, he shrugged and said, “One more reason I’ve never been much impressed with the world.”

In the end, the gods failed.

When all the bodies had been burned or washed away, when Dombâng’s ancient worship was finally crushed, when the old ways had been nearly scrubbed out by the invaders, the causeway remained, a forty-mile spear lodged in the city’s heart. Wagons and muleteers replaced soldiers on the huge wooden bridge. A tool of war became just another piece of infrastructure. Built more than a dozen feet above the water and the rushes below, it provided the only safe passage for travelers mounted or afoot over the deadly morass.

Safe, that is, as long as it didn’t collapse.

Unlike most of the people trapped on the failing span, I’d waited until we were halfway down, then leapt well clear of the railings, the falling bodies, and the limbs of the panicked, thrashing beasts. I would have landed well, had the ground been solid. As it was, both feet plunged into the mud, and I found myself mired well past my knees. I tried to pull free. Failed. The panic of all trapped things slid a cold feather down my spine. The air was ablaze with screams, broken people and beasts of burden writhing their way deeper into the mud while those who were still whole tried to help or flee, clawing their way through the water and mud toward loved ones or safety.

I forced myself to watch as one man, stuck hip-deep in the channel, thrashed and thrashed and then collapsed, crumpling as though he were made of paper.

Don’t be like him, I told myself. If today is the day you meet the god, then go with grace.

The thought steadied me. Whatever childhood terror ached in my bones, I was no longer a child. Death held no sting, so why should any of the rest of it?

I turned my attention back to my own predicament. This time I tested each leg slowly, deliberately. They were stuck fast, but I found I could slide inside my leather pants just slightly. I loosened my belt, managed to writhe another few inches free before the hilts of the knives strapped to my thighs snagged on the inside of the fabric.

Behind me, the chorus of screams found a new pitch. I glanced over my shoulder to see half a dozen crocs floating silently up the channel, backs and eyes just breaking the silty water. As I watched, one of them slipped below the surface, and a moment later one of the women who had been churning up the channel with her own panic offered a final, baffled scream before being yanked out of sight.

Slowly, I told myself, sliding a hand down inside my pants, pulling the knives free one at a time, then laying them on the mud in front of me. Slowly.

With the knives clear, I could move once more. I leaned forward, dug my fingers into the sloppy mud, then dragged myself free gradually as a snake molting last season’s skin.

Free, of course, was hardly the same thing as safe.

The broken section of causeway had dumped more than a hundred people into the swamp when it collapsed. At least half of them were stuck, thrashing, bleeding, screaming—doing everything necessary, in other words, to attract the delta’s most eager predators. If I’d been alone, I might have tried to creep slowly through the mud toward safety. With the crocs already circling, however, and the snakes tasting the air with their flicked, forking tongues, there was no time for creeping. Already the sluggish water of the channel a dozen feet away was turning russet with blood.

The way out was obvious. The causeway had collapsed onto its side, snapped pilings stabbing sideways like broken legs, what had been the western railing buried in the mud and the wreckage of the rushes, eastern railing suddenly horizontal, like the scaffolding of a walkway robbed of its planking. I’d landed about fifteen feet from the wreckage, but if I could get back to it, get on top of that railing, I could follow it a hundred paces or so to where it had ripped free of the rest of the causeway. The wood was snapped and broken in two dozen places, but it would beat slogging through the mud or trying to swim the swirling channels.

As I ran my eyes along the span, searching for the best way up, I realized my Witnesses were already atop it, Kossal standing on the railing, arms crossed over his chest, Ela straddling it, open parasol on her shoulder, shielding her face from the sun, sandaled feet dangling as she kicked her legs. The older priest pointed toward me, Ela narrowed her eyes, then smiled and waved. They might have been at a picnic, or an open-air concert, the horrified screams spangled across the air no more than the discordant music of musicians tuning their instruments.

Ela waved me over gaily. I could barely hear her voice above the clamor: “What are you doing, Pyrre? Come on!”

I retrieved my knives, sheathed them against my bare thighs. My drawers had stayed on when my pants slipped off, but they’d offer almost no protection against snakes or crocs. The safest thing was to get out of the mud as quickly as possible, which meant moving straight through a knot of men and women stuck between me and the causeway.

Two crocs had closed in on them from the south. One of the women—slender as a reed, but fierce—was using a four-foot spar of shattered wood to smash at the beasts over and over while two men struggled to drag a fourth companion free of the murk. For the moment, the wood-wielder had managed to hold the two beasts at bay. It was obvious, however, that she wouldn’t hold them much longer. Already, the smaller of the two crocs had started to slide to the side, flanking her. Worse, she stood up past her knees in the bloody water, so focused on the crocs she had forgotten the other dangers posed by the delta.

I skirted behind her, aiming for the closest section of the fallen causeway while also giving the group an ample berth. I didn’t want to get pulled into the chaos of their struggle. As I neared the wrecked wooden structure, however, I realized for the first time how high above the mud the railing hung. The causeway had been easily wide enough for two wagons to pass, which meant that, tipped on its side, even buried in the mud, it presented a vertical wall more than twice my own height.

Off to the west, screams crescendoed. I glanced over. Two men were lumbering through the water, trying, like me, to reach the safety of the causeway. Just behind them, a third man had fallen to his knees, his mouth torn open in a horrified howl. Around him, something boiled the water to a red-brown froth.

“Qirna,” someone screamed, as though the announcement could do any good.

The first victim clutched pointlessly at his companions, who hadn’t spared a look back, then collapsed into the soaked violence of his own unmaking, screams swallowed in the greater chorus. A moment later the next man in the channel stumbled, then the other, devoured before they could cross to the mud-bank beyond.

Luckily for me, I didn’t have a channel to cross to reach the causeway. Of course, that still left me confronting the wooden wall. A few paces down the wreckage, some planks had sprung free during the collapse, offering jagged and unreliable holds for hands and feet. Less luckily, these were immediately beside the woman doing battle with the crocs.

“Pyrre!” I glanced up to find Ela grinning at me from beneath the sun-drenched halo of her parasol. “Are you coming up here, or what?”

“You could throw me a rope.”

She laughed, as though I’d made the most delightful joke. “I don’t have a rope. Besides, what fun would that be?”

“You do realize,” Kossal interjected testily, “that we still have fifteen miles to walk today. We could have skipped all this if you’d stayed on the causeway.”

He offered this last crack as though staying on the causeway had been an obvious option.

“Feel free to go on without me,” I said. “I’ll catch up.”

Ela shook her head. “Don’t listen to him. We’re happy to wait. It’s a gorgeous morning.”

The poor fools a pace away didn’t seem to agree. In trying to drag their friend out of the mud they had succeeded mostly in further miring themselves. One of the men—long-haired, square-jawed, narrow-waisted—caught my eye as he strained on the girl’s wrist.

“Please,” he gasped. “Help us.”

He was up to his knees in the mud and sinking deeper by the moment. Just over his shoulder, the woman with the stick was losing her battle. Despite the ferocity of her attacks, the crocs had backed her all the way into her companions, snapping at the shard of wood whenever it came close. She was beginning to flag, propped up at this point mostly by her desperation.

“Pyrre,” Ela called down from above. “This is the work of the god.”

I stared, frozen for just a moment, at the four people battling for their own lives.

“No,” I replied after a moment, shaking my head. “Not yet, it’s not.”

What I did next may seem like a strange decision for a servant of Ananshael. The truth was, I wasn’t bothered by the weight of my god gathered in the air around us. Ananshael is everywhere, always. Nor did I have anything against the crocodiles, which seemed magnificent beasts, more than capable of the god’s message. It was the intervening moments that troubled me; not the struggle itself, but the pointlessness of that struggle. When one of our priestesses takes a life, she does so quickly, cleanly. If these men and women were going to die, I wanted them to die. If they were going to fight, I wanted them to fight. Instead, they occupied an awful middle ground, a hopeless territory that did not belong to Ananshael, but to fear and pain. I remembered fear and pain all too well from my childhood. It was to escape them that I had first turned to my god.

“Lie down,” I said, gesturing toward the mud in front of the trapped woman.

The man stared at me, baffled.

“Lie down,” I said again. “You’re sinking because your feet are small. Your body is large. Lie down and let her use you to climb out.”

It took him a moment to understand, then he nodded, dragged his own feet from the mud with great sucking sounds, and hurled himself down onto the mud before the woman. The other man wrenched himself free, sat on his friend’s back, and from that more stable platform managed to begin hauling the trapped woman, inch by agonizing inch, from the mud’s grip.

Behind them, the woman with the stick lashed out, landed a blow squarely on the nose of one of the crocs, forcing the beast to retreat. The other, sensing a shift in the fight, subsided a few feet into the water.

“Is she out?” she shouted without turning. “Is she fucking out?”

“Almost,” gasped the man lying in the mud. “Are you all right, Bin?”

The woman with the stick—Bin, evidently—had doubled over, hands on her knees, sucking air. For a moment she couldn’t respond.

“Bin!” the man bellowed, his voice ragged with sudden panic. “Are you all right?”

He couldn’t see her from where he was, face shoved down into the mud.

“She’s fine,” I said. “She’s forced them back.”

“There!” shouted the second man, sitting back in the mud as the trapped woman came suddenly free. “She’s out, Bin. She’s out. Come on.”

“This way,” I said, gesturing toward the causeway.

They stared, lost, each one, in the private labyrinth of their own panic. There was no time to explain.

“Follow me,” I said, turning to the wooden wreckage and beginning to climb.

My feet and hands were slick with mud, making even the most generous holds treacherous. There were spots where I had to hold on by the tips of my fingers. Twice, the board I was holding ripped free with a furious shriek; each time I managed to catch myself. When I looked down, I could see the first woman, the one who had been stuck, following me up, eyes wide as saucers, the tendons of her neck and back straining. I doubt she’d ever climbed anything more strenuous than a ladder, but her fear made her strong, and each board I tore free offered a more secure handhold to those that followed.

“You’re close now,” I called down to her.

She met my eyes, nodded, and kept climbing.

We almost made it. Or maybe that’s not quite the right pronoun.

I did make it, as did the woman who’d been following me, and the man after her. While they climbed, the other two—the man who’d thrown himself down in the mud and Bin—held off the crocs, lashing out with their sticks every time the creatures got close. They weren’t going to hold them forever, but they didn’t need to. They just needed time for their companions to get clear, and then the woman was climbing while the man, a jagged length of wood in each hand, battered the beasts. The crocs backed off a few feet; he hurled his meager weapons at their faces, turned, and began to climb.

I watched from the railing above, chest heaving with the recent effort.

“Well,” Ela said, draping her arm around my shoulders. “For a servant of Ananshael, you’ve made some curious decisions today.”

I just shook my head, wordless, unsure how to explain.

Below, the crocs gnashed their teeth, churned the water with their tails.

“Come on, Vo,” bellowed the man beside me, reaching down through the railing toward his companions. “You’re almost there. Come on, Bin, keep climbing!”

She was close, close enough to reach a hand toward him. When she did, the board she’d been holding tore free. She seemed to hang there a moment, caught on an invisible line; then she fell backward, trailing her scream behind her. She landed badly, leg lodged in the mud, bent all wrong. The crocs turned, their movement so graceful it might have been choreographed.

“Make way,” Ela murmured, “for the million-fingered god.”

The other climber, Vo, turned. I caught a glimpse of the horror carved across his features.

“Get up, Bin!” he pleaded. “Get up!”

Then, when it was obvious she wouldn’t be getting up, he jumped.

“That seemed ill-advised,” Ela mused.

Kossal grunted. “We’re not going to get to Dombâng any quicker for watching this nonsense.”

“Since when,” Ela asked, turning on him, “is the work of our lord nonsense?”

“The work of our lord is happening everywhere,” Kossal replied. “All the time. You plan to stop every time some insect expires mid-flight? Whenever we have the chance to see a few fish hauled up in a net?”

“This,” Ela said, nodding to the scene below, “is more interesting than fish.”

Kossal glanced down, then shook his head. “Not really.”

Ela elbowed him in the ribs. “Don’t be dull. It’s instructive, at the very least.”

“I don’t need instruction on how to die in the jaws of an oversized lizard.”

“Not for you, you old goat, for Pyrre.” She nodded toward the long-haired man, who’d managed somehow to get his footing in the deep, treacherous mud. “That,” she said, smiling contentedly, “is love.”

“Stupidity,” Kossal grumbled.

Ela shrugged. “It’s a fine line, sometimes, between the two.”

If it was a fine line, the painters and sculptors down through the ages had managed to stay on one side of it. Artistic depictions of love tended to focus on softer subjects: lush lips, rumpled beds, the curve of a naked hip. Fewer crocodiles, certainly. Far less screaming.

“Would you fight a crocodile,” Ela pressed, elbowing Kossal again, “to save me?”

“You are a priestess of Ananshael,” Kossal observed tartly. “When the beast comes, I expect you to embrace it.”

“Doesn’t seem to be working for him,” Ela pointed out.

Vo, too, had landed badly. While he seemed unbroken, the twin pieces of wood he’d used to hold off the beasts had disappeared. The nearest of the two creatures was bearing down on the injured woman. No weapon to hand, a scream of defiance hot in his throat, the man leaped. He landed on the croc’s back, somehow avoiding those massive, snapping jaws. The beast thrashed, churning the muddy water to a froth with its tail, while Vo clung on, arms wrapped around the crocodile’s neck, face pressed against the wet, glistening hide.

“That’s how they do it in the fights,” I said. “Get behind the thing, get on its back. Get an arm around the neck, then go to work with the knife.”

“He doesn’t have a knife,” Ela pointed out.

Bin had managed to tear herself free of the mud, to drag herself a few feet along the channel’s bank, away from both the churning fury of the crocodile and the causeway itself. Beside me, her companions were screaming.

“I’m going to give him one,” I said, slipping a blade from the sheath on my thigh.

“Waste of a good knife,” Kossal said.

“I’ve got others.”

The knife landed with a wet thwock in the mud, blade down, well within reach of the desperate man. Locked in his battle with the croc, he didn’t notice. Afternoon sun gleamed off the steel, but his eyes were squeezed shut. Bin, blind with terror, blundered into the water. In fact, no one at all had noticed my throw. All eyes were fixed on the struggle below.

“I take it back,” Kossal said.

Ela broke into a wide smile. “That might be a first!” Then she narrowed her eyes. “Just what is it, exactly, that you’re taking back?”

Kossal gestured to the man as the croc thrashed back into the water and rolled. “It is excellent instruction in the ways of love.”

“Love,” Ela explained patiently, “was in the jumping off the causeway to protect the woman.”

“Love,” Kossal countered, “is hurling yourself onto a deadly creature, then realizing once you get hold there’s no way to let go. Either you die, or it does.”

He didn’t look at the woman as he spoke, but Ela threaded her arm through his. “Surely I’m a good deal more attractive and obliging than a crocodile.”

“Marginally.”

The creature stayed below for three heartbeats, five, ten. The water roiled where it had disappeared, as though someone had kindled a great fire below the surface. A few feet away, Bin stumbled to her knees in the water, then her screams broke into an entirely new range. A moment later, a red stain bled through the mud-brown water around her.

The crocodile rolled upright, hurling the man from his back onto the bank. He was obviously exhausted, bleeding from his scalp and shoulder, his shirt half torn away, but he hadn’t given up.

“I’m coming,” he shouted, gesturing to the woman. “Just get to the causeway and you’ll be all right.”

“No,” she screamed. “They have me. They have me.”

I shook my head. “I’m ending it.”

Kossal turned to study me. “The beasts of the land and of the water were the god’s servants long before our order.”

“And this is the Trial,” Ela reminded me. “There are rules to observe.”

Both my blades were in the air before she finished speaking. One took the woman square in the chest. The other sliced through the man’s throat before splashing into the water beyond.

Kossal turned to me, old face grave. “The offerings of the Trial are prescribed by the song. To go outside of them is to fail.”

I shook my head, pointing. “She said they had her: One who is right. He said he was coming: One who is wrong.”

Kossal raised an eyebrow. Ela just started laughing.

“I expect this will prove a delightful trip.”

Staring down into the blood and mud, listening to the screams shaking the air around me, hearing my own pulse thudding in my ears, remembering all the old feelings I’d thought long banished or forgotten, I wasn’t sure I agreed.

Copyright © 2017 by Brian Staveley

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

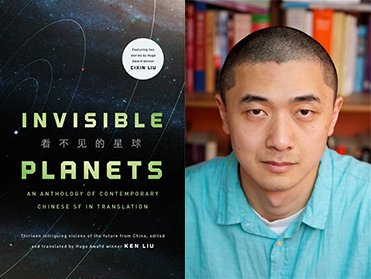

Ruthanna Emrys’ Innsmouth Legacy, which began with Winter Tide and continues with Deep Roots, confronts H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos head-on, boldly upturning his fear of the unknown with a heart-warming story of found family, acceptance, and perseverance in the face of human cruelty and the cosmic apathy of the universe. Emrys brings together a family of outsiders, bridging the gaps between the many people marginalized by the homogenizing pressure of 1940s America.

Ruthanna Emrys’ Innsmouth Legacy, which began with Winter Tide and continues with Deep Roots, confronts H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos head-on, boldly upturning his fear of the unknown with a heart-warming story of found family, acceptance, and perseverance in the face of human cruelty and the cosmic apathy of the universe. Emrys brings together a family of outsiders, bridging the gaps between the many people marginalized by the homogenizing pressure of 1940s America. One decision. Thousands of lives ruined. Can someone ever repent for the sins of their past?

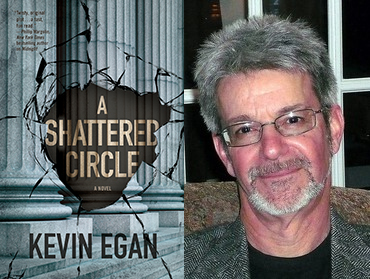

One decision. Thousands of lives ruined. Can someone ever repent for the sins of their past? When one leader gives the Judge a powerful device that predicts the future, the Judge doesn’t want to believe its chilling prophecy: The world will soon end, and he’s to blame. But bad things start to happen. His wife and children are taken. His friends are falsely imprisoned. His closest allies are killed. Worst of all, the world descends into a cataclysmic global war.

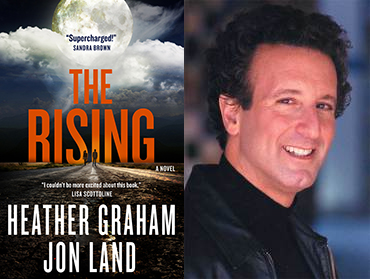

When one leader gives the Judge a powerful device that predicts the future, the Judge doesn’t want to believe its chilling prophecy: The world will soon end, and he’s to blame. But bad things start to happen. His wife and children are taken. His friends are falsely imprisoned. His closest allies are killed. Worst of all, the world descends into a cataclysmic global war. Another Hollywood night, another job for electric-detective-turned-robotic-hitman Raymond Electromatic. The target is a tall man in a black hat, and while Ray completes his mission successfully, he makes a startling discovery—one he soon forgets when his 24-hour memory tape loops to the end and is replaced with a fresh reel…

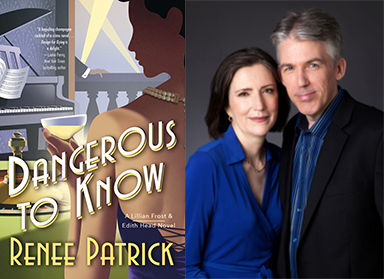

Another Hollywood night, another job for electric-detective-turned-robotic-hitman Raymond Electromatic. The target is a tall man in a black hat, and while Ray completes his mission successfully, he makes a startling discovery—one he soon forgets when his 24-hour memory tape loops to the end and is replaced with a fresh reel… When seventeen-year-old senator’s son Grant Tavish is involved in a fatal accident, all he wants to do is face the consequences of what he’s done. But those consequences never come, even if headlines of “affluenza” do. The truth soon becomes clear: due to his father’s connections, Grant is going to get away with murder.

When seventeen-year-old senator’s son Grant Tavish is involved in a fatal accident, all he wants to do is face the consequences of what he’s done. But those consequences never come, even if headlines of “affluenza” do. The truth soon becomes clear: due to his father’s connections, Grant is going to get away with murder. Pyrre Lakatur is not, to her mind, an assassin, not a murderer—she is a priestess. At least, she will be once she passes her final trial. To complete her trial, Pyrre has ten days to kill the seven people enumerated in an ancient song, including “the one who made your mind and body sing with love / who will not come again.”

Pyrre Lakatur is not, to her mind, an assassin, not a murderer—she is a priestess. At least, she will be once she passes her final trial. To complete her trial, Pyrre has ten days to kill the seven people enumerated in an ancient song, including “the one who made your mind and body sing with love / who will not come again.”