opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

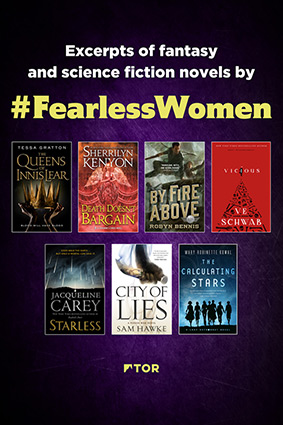

opens in a new window Welcome to #FearlessWomen! Today we’re featuring an excerpt from The Calculating Stars, Mary Robinette Kowal’s alternate history of the space race.

Welcome to #FearlessWomen! Today we’re featuring an excerpt from The Calculating Stars, Mary Robinette Kowal’s alternate history of the space race.

On a cold spring night in 1952, a meteorite falls to earth and destroys much of the eastern seaboard of the United States, including Washington D.C. The Meteor, as it is popularly known, decimates the U.S. government and paves the way for a climate cataclysm that will eventually render the earth inhospitable to humanity.This looming threat calls for a radically accelerated timeline in the earth’s efforts to colonize space, and allows a much larger share of humanity to take part in the process.

One of these new entrants in the space race is Elma York, whose experience as a WASP pilot and mathematician earns her a place in the International Aerospace Coalition’s attempts to put man on the moon. But with so many skilled and experienced women pilots and scientists involved with the program, it doesn’t take long before Elma begins to wonder why they can’t go into space, too—aside from some pesky barriers like thousands of years of history and a host of expectations about the proper place of the fairer sex. And yet, Elma’s drive to become the first Lady Astronaut is so strong that even the most dearly held conventions may not stand a chance against her.

opens in a new windowThe Calculating Stars will be available on July 3rd. Please enjoy this excerpt.

Chapter One

PRESIDENT DEWEY CONGRATULATES NACA ON SATELLITE LAUNCH

March 3, 1952—(AP)—The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics successfully put its third satellite into orbit, this one with the capability of sending radio signals down to Earth and taking measurements of the radiation in space. The president denies that the satellite has any military purpose and says that its mission is one of scientific exploration.

Do you remember where you were when the Meteor hit? I’ve never understood why people phrase it as a question, because of course you remember. I was in the mountains with Nathaniel. He had inherited this cabin from his father and we used to go up there for stargazing. By which I mean: sex. Oh, don’t pretend that you’re shocked. Nathaniel and I were a healthy young married couple, so most of the stars I saw were painted across the inside of my eyelids.

If I had known how long the stars were going to be hidden, I would have spent a lot more time outside with the telescope.

We were lying in the bed with the covers in a tangled mess around us. The morning light filtered through silver snowfall and did nothing to warm the room. We’d been awake for hours, but hadn’t gotten out of bed yet for obvious reasons. Nathaniel had his leg thrown over me and was snuggled up against my side, tracing a finger along my collarbone in time with the music on our little battery-powered transistor radio.

I stretched under his ministrations and patted his shoulder. “Well, well . . . my very own ‘Sixty Minute Man.’”

He snorted, his warm breath tickling my neck. “Does that mean I get another fifteen minutes of kissing?”

“If you start a fire.”

“I thought I already did.” But he rolled up onto his elbow and got out of bed.

We were taking a much needed break after a long push to prepare for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’s launch. If I hadn’t also been at NACA doing computations, I wouldn’t have seen Nathaniel awake anytime during the past two months.

I pulled the covers up over myself and turned on my side to watch him. He was lean, and only his time in the Army during World War II kept him from being scrawny. I loved watching the muscles play under his skin as he pulled wood off the pile under the big picture window. The snow framed him beautifully, its silver light just catching in the strands of his blond hair.

And then the world outside lit up.

If you were anywhere within five hundred miles of Washington, D.C., at 9:53 a.m. on March 3rd, 1952, and facing a window, then you remember that light. Briefly red, and then so violently white that it washed out even the shadows. Nathaniel straightened, the log still in his hands.

“Elma! Cover your eyes!”

I did. That light. It must be an A-bomb. The Russians had been none too happy with us since President Dewey took office. God. The blast center must have been D.C. How long until it hit us? We’d both been at Trinity for the atom bomb tests, but all of the numbers had run out of my head. D.C. was far enough away that the heat wouldn’t hit us, but it would kick off the war we had all been dreading.

As I sat there with my eyes squeezed shut, the light faded.

Nothing happened. The music on the radio continued to play. If the radio was playing, then there wasn’t an electromagnetic pulse. Hence, it hadn’t been an A-bomb. I opened my eyes. “Right.” I hooked a thumb at the radio. “Clearly not an A-bomb.”

Nathaniel had spun away to get clear of the window, but he was still holding the log. He turned the log over in his hands and glanced back at the window. “There hasn’t been any sound yet. How long has it been?”

The radio continued to play and it was still “Sixty Minute Man.” What had that light been? “I wasn’t counting. A little over a minute?” I shivered as I did the speed-of-sound calculations and the seconds ticked by. “Zero point two miles per second. So the center is at least twenty miles away?”

Nathaniel paused in the process of grabbing a sweater and the seconds continued to tick by. Thirty miles. Forty. Fifty. “That’s . . . that’s a big explosion to have been that bright.”

Taking a slow breath, I shook my head, more out of desire for it not to be true than out of conviction. “It wasn’t an A-bomb.”

“I’m open to other theories.” He hauled his sweater on, the wool turning his hair into a haystack of static.

The music changed to “Some Enchanted Evening.” I got out of bed and grabbed a bra and the trousers I’d taken off the day before. Outside, snow swirled past the window. “Well . . . they haven’t interrupted the broadcast, so it has to be something fairly benign, or at least localized. It could be one of the munitions plants.”

“Maybe a meteor.”

“Ah!” That idea had some merit and would explain why the broadcast hadn’t been interrupted. It was a localized thing. I let out a breath in relief. “And we could have been directly under the flight path. That would explain why there hasn’t been an explosion, if what we were seeing was just it burning up. All light and fury, signifying nothing.”

Nathaniel’s fingers brushed mine and he took the ends of the bra out of my hand. He hooked the strap and then he ran his hands up my shoulder blades to rest on my upper arms. His hands were hot against my skin. I leaned back into his touch, but I couldn’t quite stop thinking about that light. It had been so bright. He squeezed me a little, before releasing me. “Yes.”

“Yes, it was a meteor?”

“Yes, we should go back.”

I wanted to believe that it was just a fluke, but I had been able to see the light through my closed eyes. While we got dressed, the radio kept playing one cheerful tune after another. Maybe that was why I pulled on my hiking boots instead of loafers, because some part of my brain kept waiting for things to get worse. Neither of us commented on it, but every time a song ended, I looked at the radio, certain that this time someone would tell us what had happened.

The floor of the cabin shuddered.

At first I thought a heavy truck was rolling past, but we were in the middle of nowhere. The porcelain robin that sat on the bedside table danced along its surface and fell. You would think that, as a physicist, I would recognize an earthquake faster. But we were in the Poconos, which was geologically stable.

Nathaniel didn’t worry about that as much and grabbed my hand, pulling me into the doorway. The floor bucked and rolled under us. We clung to each other like in some sort of drunken foxtrot. The walls twisted and then . . . then the whole place came down. I’m pretty sure that I yelled.

When the earth stopped moving, the radio was still playing.

It buzzed as if a speaker were damaged, but somehow the battery kept it going. Nathaniel and I were lying, pressed together, in the remnants of the doorframe. Cold air swirled around us. I brushed the dust from his face.

My hands were shaking. “Okay?”

“Terrified.” His blue eyes were wide, but both pupils were the same size, so . . . that was good. “You?”

I paused before answering with the social “fine,” took a breath, and did an inventory of my body. I was filled with adrenaline, but I hadn’t wet myself. Wanted to, though. “I’ll be sore tomorrow, but I don’t think there’s any damage. To me, I mean.”

He nodded and craned his neck around, looking at the little cavity we were buried inside. Sunlight was visible through a gap where one of the plywood ceiling panels had fallen against the remnants of the doorframe. It took some doing, but we were able to push and pry the wreckage to crawl out of that space and clamber across the remains of the cabin.

If I had been alone . . . Well, if I had been alone, I wouldn’t have gotten into the doorway in time. I wrapped my arms around myself and shivered despite my sweater.

Nathaniel saw me shiver and squinted at the wreckage. “Might be able to get a blanket out.”

“Let’s just go to the car.” I turned, praying that nothing had fallen on it. Partly because it was the only way to the airfield where our plane was, but also because the car was borrowed. Thank heavens, it was sitting undamaged in the small parking area. “There’s no way we’ll find my purse in that mess. I can hot-wire it.”

“Four minutes?” He stumbled in the snow. “Between the flash and the quake.”

“Something like that.” I was running numbers and distances in my head, and I’m certain he was, too. My pulse was beating against all of my joints and I grabbed for the smooth certainty of mathematics. “So the explosion center is still in the three-hundred-mile range.”

“The airblast will be what . . . half an hour later? Give or take.” For all the calm in his words, Nathaniel’s hands shook as he opened the passenger door for me. “Which means we have another . . . fifteen minutes before it hits?”

The air burned cold in my lungs. Fifteen minutes. All of those years doing computations for rocket tests came into terrifying clarity. I could calculate the blast radius of a V2 or the potential of rocket propellant. But this . . . this was not numbers on a page. And I didn’t have enough information to make a solid calculation. All I knew for certain was that, as long as the radio was playing, it wasn’t an A-bomb. But whatever had exploded was huge.

“Let’s try to get as far down the mountain as we can before the airblast hits.” The light had come from the southeast. Thank God, we were on the western side of the mountain, but southeast of us was D.C. and Philly and Baltimore and hundreds of thousands of people.

Including my family.

I slid onto the cold vinyl seat and leaned across it to pull out wires from under the steering column. It was easier to focus on something concrete like hot-wiring a car than on whatever was happening.

Outside the car, the air hissed and crackled. Nathaniel leaned out the window. “Shit.”

“What?” I pulled my head out from under the dashboard and looked up, through the window, past the trees and the snow, and into the sky. Flame and smoke left contrails in the air. A meteor would have done some damage, exploding over the Earth’s surface. A meteorite, though? It had actually hit the Earth and ejected material through the hole it had torn in the atmosphere. Ejecta. We were seeing pieces of the planet raining back down on us as fire. My voice quavered, but I tried for a jaunty tone anyway. “Well . . . at least you were wrong about it being a meteor.”

I got the car running, and Nathaniel pulled out and headed down the mountain. There was no way we would make it to our plane before the airblast hit, but I had to hope that it would be protected enough in the barn. As for us . . . the more of the mountain we had between us and the airblast, the better. An explosion that bright, from three hundred miles away . . . the blast was not going to be gentle when it hit.

I turned on the radio, half-expecting it to be nothing but silence, but music came on immediately. I scrolled through the dial looking for something, anything that would tell us what was happening. There was just relentless music. As we drove, the car warmed up, but I couldn’t stop shaking.

Sliding across the seat, I snuggled up against Nathaniel. “I think I’m in shock.”

“Will you be able to fly?”

“Depends on how much ejecta there is when we get to the airfield.” I had flown under fairly strenuous conditions during the war, even though, officially, I had never flown combat. But that was only a technical specification to make the American public feel more secure about women in the military. Still, if I thought of ejecta as anti-aircraft fire, I at least had a frame of reference for what lay ahead of us. “I just need to keep my body temperature from dropping any more.”

He wrapped one arm around me, pulled the car over to the wrong side of the road, and tucked it into the lee of a craggy overhang. Between it and the mountain, we’d be shielded from the worst of the airblast. “This is probably the best shelter we can hope for until the blast hits.”

“Good thinking.” It was hard not to tense, waiting for the airblast. I rested my head against the scratchy wool of Nathaniel’s jacket. Panicking would do neither of us any good, and we might well be wrong about what was happening.

A song cut off abruptly. I don’t remember what it was; I just remember the sudden silence and then, finally, the announcer. Why had it taken them nearly half an hour to report on what was happening?

I had never heard Edward R. Murrow sound so shaken. “Ladies and gentlemen . . . Ladies and gentlemen, we interrupt this program to bring you some grave news. Shortly before ten this morning, what appears to have been a meteor entered the Earth’s atmosphere. The meteor has struck the ocean just off the coast of Maryland, causing a massive ball of fire, earthquakes, and other devastation. Coastal residents along the entire Eastern Seaboard are advised to evacuate inland because additional tidal waves are expected. All other citizens are asked to remain inside, to allow emergency responders to work without interruption.” He paused, and the static hiss of the radio seemed to reflect the collective nation holding our breath. “We go now to our correspondent Phillip Williams from our affiliate WCBO of Philadelphia, who is at the scene.”

Why would they have gone to a Philadelphia affiliate, instead of someone at the scene in D.C.? Or Baltimore?

At first, I thought the static had gotten worse, and then I realized that it was the sound of a massive fire. It took me a moment longer to understand. It had taken them this long to find a reporter who was still alive, and the closest one had been in Philadelphia.

“I am standing on the US-1, some seventy miles north of where the meteor struck. This is as close as we were able to get, even by plane, due to the tremendous heat. What lay under me as we flew was a scene of tremendous devastation. It is as if a hand had scooped away the capital and taken with it all of the men and women who resided there. As of yet, the condition of the president is unknown, but—” My heart clenched when his voice broke. I had listened to Williams report the Second World War without breaking stride. Later, when I saw where he had been standing, I was amazed that he was able to speak at all. “But of Washington itself, nothing remains.”

Copyright © 2018 by Mary Robinette Kowal

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Mary Robinette Kowal — $3.99

by Mary Robinette Kowal — $3.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Gene Wolfe — $3.99

by Gene Wolfe — $3.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Juliet Marillier — $3.99

by Juliet Marillier — $3.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

by Daniel Abraham — $3.99

by Daniel Abraham — $3.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

by Sara Douglass — $3.99

by Sara Douglass — $3.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

by Terry Goodkind — $3.99

by Terry Goodkind — $3.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

by David Edison — $2.99

by David Edison — $2.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

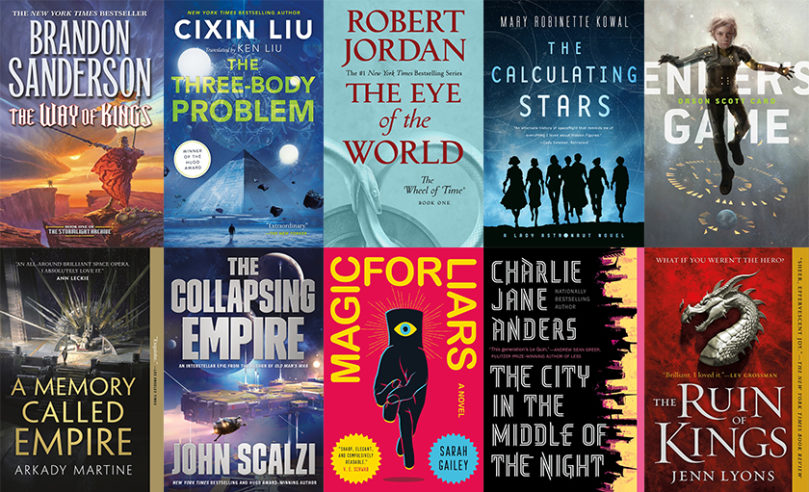

The Calculating Stars

The Calculating Stars Lent

Lent

Deadmen Walking

Deadmen Walking The Future of Another Timeline

The Future of Another Timeline Magic for Liars

Magic for Liars Old Man’s War

Old Man’s War The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Ender’s Shadow

Ender’s Shadow The Word for World is Forest

The Word for World is Forest The Way of Kings

The Way of Kings A Darker Shade of Magic

A Darker Shade of Magic