opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

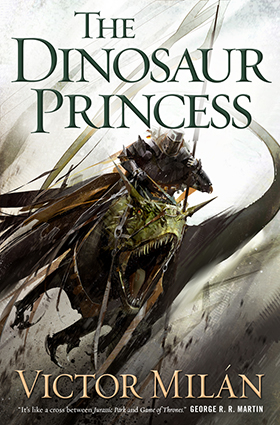

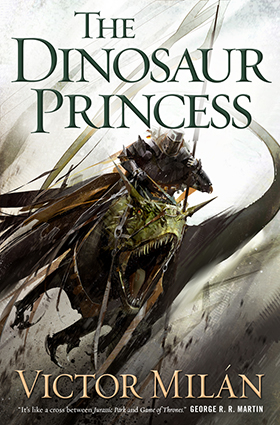

Humans were abducted eons ago at a god’s whim. Empires have risen and fallen and now men ride into battle on Triceratops and their generals lead them on White Thunder T-Rexes. Welcome to Paradise, and the third volume in Victor Milán’s glorious alternate fantasy universe.

The ancient gods who brought mankind to Paradise have returned to judge their human experiment. The Grey Angels, fabled ancient weapons of the gods, have come to rid the world of sin.

And if humans are deemed unworthy, they will be scourged from the face of Paradise.

opens in a new windowThe Dinosaur Princess will become available August 15th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

Prologue

El Mundo Debajo, The World Below. . . .—The fabulous realm, claimed by legend to lie beneath the very soil of Paradise, in which the Creators’ servitors, the seven Grey Angels, make Their home. Mortal humans cannot reach there, but only supernatural beings. Some stories claim that the hada, the Fae, dwell there as well. But those are probably only fables made up to frighten bad children, not like you or me.

The Grey Angel Raguel’s Dream, the World Below

“Face facts,” said Uriel to his host. “You had your chance. And you blew it.”

Raguel sighed dramatically. He sat with knees crossed and hands around the upper one on a jut of ice like a small pressure-ridge. His dream-armor was plate made of ice. Uriel knew he was particularly vain about the effect of the fluting he’d made in its breastplate and limb-armor this time.

“Also, why do you insist on keeping it so blasted cold?” Uriel asked.

“You’re Fire, I’m Ice,” Raguel said. “What do you expect? I find your own Dream beastly hot, you know. Anyway, why are you complaining? Now you get to try your soft Fundamentalist hand at dealing with the human pestilence while I have to rusticate here in exile.”

“You can go fight the Uncreated.”

“To what end? We’ve been doing that for trillions of cycles and aren’t any closer to winning that I can see.”

Uriel was lean, though not gaunt like his Instrumentality or Raguel’s. His own plate armor was green; the cloth-mimicking cape that fluttered from his shoulder-guarding pauldrons, red like flame. He currently favored a clean-shaven appearance, skin rather pallid to contrast with a thatch of black hair, and eyes of green—the prime color of his Patron Creator, Telar, the Oldest Daughter.

“Defeatism?” he asked softly. “Be careful whom you let hear talking that way, my friend.”

Raguel shot him a glare. When an Angel intended, such glares could wound. Even another Grey Angel. Especially here in Raguel’s own dream, which he had constructed for himself Below.

But Uriel felt no fear. Such acts had consequences. No Angel had ever actually Ended another. But they knew to fear it. Especially given that, in their endless war, they were few, and the Fae, innumerable. And Uriel was a friend.

“Let me back into the fray Above, and I’ll show you how ‘defeatist’ I am,” Raguel said.

“Rules are rules, Ice,” Uriel said. “You failed. Now you wait your turn again. Unless you care to take the matter up with Michael?”

“No need to bother Him,” Raguel said. “And who is like Him? But it just wasn’t fair, how it ended. It hurt the dignity of all Angels, to have that damned overgrown lapdog bite my Instrumentality in half.”

“Then perhaps you should have been more cautious about taking it out and waving it around in order to impress the apes,” Uriel said. “In any event—”

His words ran down. He was aware that Raguel was staring at him. Then his host turned to follow his gaze toward his personal horizon.

Across the ice-sheet walked a naked woman. The winds that howled here, except in the vicinity of Raguel and his invited guest, whipped her long blond hair around her body. She seemed to enjoy the simulated feel, though it must cut her pale skin like flaying-knives.

“Look who’s here,” Uriel murmured.

“Shit,” Raguel said. He snapped to his feet. “Now this really pisses me off to no end. What do you think you’re playing at, Aphrodite, invading my space like this?”

“I am the World, Ice Angel,” she said, approaching, “and I walk where I please.”

“I wish you wouldn’t do it this way,” Uriel said. “I find it . . . disconcerting.”

She raised a brow at him. “You find the humans’ form disturbing? Look at yourself. Or is it something else?”

“I resent that form,” Raguel said. “Especially when it comes walking in here uninvited. You love the humans so much you actually enjoy appearing in their likeness.”

Like his friend, Uriel found it an exasperating irony that he had by nature the mannerisms as well as the semblance of the humans who infected the Above like a malignant mycelium. But that was his nature—the nature of all his kind. The Creators had made the Grey Angels as their special servitors. And as with the world Paradise itself and everything on it, They had made the Angels as it pleased them to.

“I do,” Aphrodite said. “I love all things of Paradise and on it. Even you, Raguel, even when you act like a sulky human child.”

Raguel sat down on his ice-jut, crossed his arms, and frowned. “How do you know how a human child acts?”

“Because I watch them,” she said. “You might consider it. Rather than exceeding the Creators’ mandate.”

She had stepped within the charmed circle of calm that Raguel, for his own convenience, kept about himself and Uriel. Now her hair rose in a crackle of electricity, and her blue eyes glared.

“Wait, now,” Uriel said. “I’m not the one here who was actively trying to exterminate the humans.”

She spun on him. “No, you are merely trying to kill most of them.”

“You’re a fine one to talk, meddling in their affairs to help them. Perhaps we’re not the only ones walking the knife edge of what our own Creation permits.”

“I do no such thing. I was made to preserve Paradise—Creation itself. As you were made to maintain Holy Equilibrium within it. I do not ‘help’ the humans. I try to counteract your insane desire to unmake what the Creators made!”

“Fancy words,” their host told her bitterly. “You helped that human pet of yours Karyl put an ignominious end to my Crusade. Even if that does fit your own built-in restrictions enough that you didn’t destroy yourself, it’s still infringing on our prerogative. You do not rule the Angels, World-Spirit!”

In response she spread her arms. Around Uriel and his friend sprang up Paradise. The icy wasteland—so rare Above—turned to the lush and riotous green and tiny explosions of red and purple and white and gold of some flower-filled clearing in a forest of cycads and lordly conifers. Raguel cried out—whether in surprise or in pain from the touch of warm, humid Tropical air, Uriel didn’t know.

“What are you doing?” Raguel shouted, jumping up again and waving his arms. “My Dream!”

“Indeed I do not rule you,” Aphrodite said, “but I am the Caretaker of the World. From the outer air clear down to the core. And I have the power needed to carry out my mission.”

Raguel held up his hands. To Uriel he looked as if he felt really sick. Uriel thought he understood; he himself was feeling vulnerable in a way none of the Seven had since—well, since the end of the great surface War against the Fae and their blasphemous human allies. And its fearful aftermath.

“Please, Caretaker,” Raguel said. “Please—heal my Dream. You have made your point.”

“But not sufficiently that either of you will desist,” she said.

Raguel hung his simulacrum head.

“I won’t either,” Uriel said. “Though I will echo my friend’s request. You won’t win by kicking apart his ice castle.”

“Very well.” She held out her arms again. The ice and snow and wind whirled in again to supplant the riotous green growth, until all was as before.

“I’m sorry we find ourselves at cross-purposes,” Uriel said, trying to play the peacemaker. Not even he was sure what might happen if for some reason Aphrodite simply decided to erase his friend’s Dream, with them still inside. “Truly. We know that without you we wouldn’t have a world in which to maintain Equilibrium. But you know we operate under the same constraints as you. Since none of us, neither Fundamentalist nor even Purificationist, has involuntarily destroyed himself or herself, our actions must arguably conform to the Creators’ intentions.”

“Through a long and twisted chain of reasoning,” she said.

“Nevertheless.”

A terrible, brilliant noise split the sky overhead.

Literally. Uriel saw rage twist Raguel’s face as he looked up in alarm.

Have the Fae found a way in? Uriel thought in near panic. Not just through our defenses, but into Raguel’s own sanctum? That would mean either some individual Faerie or some unprecedented demon coalition had gotten powerful enough to threaten the Angels with extinction. And thus Paradise. It was every Angel’s ultimate nightmare.

But what poured through the rift in the dense cloud cover Uriel’s host maintained above his Dream in emulation of the World Above’s perpetual daytime overcast was glorious golden light in a shape that reminded Uriel suspiciously of a vagina. A resemblance only strengthened by the winged figure descending through it.

The intruder blew another blast of her golden post-horn. Uriel winced at the sound. And the arrogance that propelled it in lieu of physical breath.

“Say what you will about her,” he murmured, “but Gabriel does know how to make an entrance.”

“You just say that because she’s one of yours,” Raguel said. “Bitch.”

“You know I can hear you, God-Friend,” the Angel called, moving her horn from her lips. She was laughing. Uriel knew that was by no means an unequivocally reassuring sign.

The sky rift closed up again, leaving the clouds the same unbroken sea seethe they had been before. Uriel knew it wasn’t by his friend’s volition. Raguel looked as angry and unsettled by the act of repair as he had by the affront of opening it in the first place.

“You’re not supposed to be here, Gabriel,” Raguel said as she touched down before him on wings as wide as a Long-crested Dragon’s. Which instantly disappeared. “Damn it.”

Uriel knew he didn’t mean that in terms of etiquette alone: an Angel’s Dream was supposed to be inviolable in fact as well as courtesy among peers. That Aphrodite had invaded, annoying though it was, shouldn’t be unexpected: she, after all, was the stuff their Dreams were made of.

But the very nature of Raguel’s personal bubble-realm, within the shared and greater Dream that was the World Below, should have made it inaccessible to any other sprite, Faerie or Grey Angel.

“You didn’t really think you could keep me out, did you, Raggy, dear?” Gabriel asked. Up close she had fine cream-colored features, a straight nose, blue eyes, and wavy red-gold hair that hung about the shoulders of the breast-and-back she wore over her yellow smock and brown leggings—the latter the colors of her Patroness, Mother Maia, the Creators’ Queen. She was strikingly beautiful to Uriel’s eyes—it was another point of resentment among the Seven that their own standards of beauty reflected those of the apes Above.

And under the circumstances, Uriel guessed that it especially rankled Raguel’s semidivine ass that Gabriel, alone of all the Grey Angels, could maintain her beautiful semblance indefinitely while walking about on the surface. Whereas when Raguel mustered and led his abortive Grey Angel Crusade, the beautiful flesh he encased his Instrumentality in had inevitably decayed into a base form that was . . . something else entirely. Though it had impressed the mortals.

“Aphrodite isn’t the only one who can walk where she pleases,” Gabriel said.

“Even into Dissonance?” Raguel asked.

Uriel winced at his friend’s gaffe. Gabriel’s eyes began to glow blue-white in fury. Literally, like vents to a supergiant star.

The rest could do that trick too, of course. But all Grey Angels were not Created equal. Gabriel’s power was second only to that of the King’s Angel, Michael. And that was before the thing Raguel had tactlessly and foolishly brought up: her captivity in the Venusberg, the hateful realm of Fae. As well as the things she did then, ostensibly under their enchantments.

“I—I,” Raguel said. He stopped and looked wild-eyed, as if some Creators’ geas had stuck his tongue to the back of his teeth. Apology did not come easy to an Angel.

Between them stepped a smaller figure. “Easy, children,” Aphrodite said with maternal good humor—and firmness.

“Out of my way, divine janitor,” Gabriel snapped. Blue lightning bolts crackled through her kinky hair, which began to lift up from the shoulders of her cuirass.

“Go ahead and blast me, Gabi, dear, if it’ll make you feel better,” Aphrodite said, smiling.

Gabriel showed her teeth. But the glow faded, the lightning died, and her hair settled back in place.

Uriel flicked his eyes toward Raguel, who shook his head in relief. None of them, possibly not even the World Witch Herself, knew what would happen if an Angel used her full destructive power on Aphrodite. Most likely nothing—but that was also the best possible case. The others were unthinkable—if all too imaginable to him.

“Let’s all try calming down,” Aphrodite said. She turned to confront Gabriel directly. “Now, God Friend, what were you thinking, barging in here like that? You Angels value your protocols so much. Surely you didn’t treat your poor brother so rudely just to stage an entrance?”

“Don’t underestimate her vanity,” murmured Uriel.

Gabriel laughed. That laughter made Uriel nervous; it was still a danger sign. Then again, since her return to the fold, most things were. All taken with all, it worried him less than the lightning and the hell glow.

“Protocols are fine,” she said. “They give the boys something to occupy their cycles. But I intended to give notice that just because Raguel here failed in his precious scheme doesn’t mean Zerachiel and I failed with him. We know what we must do for the good of Paradise and Sacred Equilibrium. And we will do it—despite your meddling and the hand-wringing concerns of Uriel, Remiel, and Raphael.”

“Shouldn’t you take that up with Michael?” Uriel asked. “He agrees: it’s my turn.”

Gabriel only laughed again. Then turning to Aphrodite, who had stepped back to reopen the circle of discussion, he said, “As for you, my dear, my answer’s simple: if our Creators don’t want us exterminating the humans, they have but to tell us so.”

“How do you dare take it on yourself to unmake what the Creators made?” Aphrodite said. She was frowning fiercely now herself, albeit without the pyrotechnics Gabriel affected.

Gabriel tossed back flame-colored hair. “And who made you ruler over us? You’re a maintenance worker. Your job is to keep the sun from burning the land and boiling the sea. We are the Creators’ appointed servants. Perhaps it’s time someone taught you to keep your place.”

Thoroughly alarmed, Uriel stepped between them. “Here, now,” he said, in what he hoped was a soothing tone. “You know we don’t dare harm Aphrodite, for fear of upsetting Sacred Equilibrium. If not returning the world to Hell.”

There was more he might have said, of course. It tickled the tip of his virtual tongue. Beasts who came from chaos and lived to spread it without love or allegiance for one another or any other thing, the Fae still almost all shared exactly that aim: to return the whole world to the state from which the Creators had remade it.

But I’m supposed to be the diplomatic one, Uriel thought. And I’m not about to repeat Raguel’s screw-up by bringing up Gabriel’s tormentors again.

“As you so kindly remind us,” Aphrodite told Gabriel, “we all have tasks we were Created for. Mine is to preserve and maintain Paradise and all its creatures; I have no wish to see anyone destroyed.”

For a moment, eyes glared into one another, sea-green and the brilliant unforgiving blue of sky momentarily left bare by a rip in the world’s daytime raiment, clouds.

“Do you grieve for an ant crushed by a Thunder-titan, then?” Gabriel asked with a sneer. But her tone was quieter than before. If not notably softened.

“Yes.”

“Well,” Gabriel said. “I’ve done what I came to do: serve notice that I don’t intend to placidly wait my turn to set things right in the world we guard.”

“And I give notice,” Aphrodite said, quite genially, “that I will stop you.”

“Wait,” said Uriel plaintively. “What about me? We all agreed on it in advance. You Purificationists had your shot. Now we Fundamentalists get to do it our way. My way. It’s the work I’ve focused on for billions of cycles! You can’t just trample on that!”

Again, Gabriel smiled.

“Just watch me, Fire of God.”

“Your Highness, may we have a word with you?” the man in the tall black hat said in a voice like warm olive oil. And a dense Griego accent.

Montserrat Angelina Proserpina Telar de los Ángeles Delgao Llobregat stopped in the middle of the corridor. It was dim, lit by nothing more than palm-oil lamps in periodic niches along the stone wall.

Are you talking to me? she wondered. While she was technically a Princess, she was the Imperial Infanta, meaning not scion of her father’s line. Alteza was an honorific more commonly addressed to her older sister, Melodía. At least by nobles, which Montse reckoned these emissaries from the Basileus Nikephoros of Trebizon must be.

Silver Mistral, Montse’s pet ferret, hopped sideways as if to block the progress of the trio of outlanders who had appeared in the door that led from the passage to an ancillary dining hall in the Firefly Palace’s sprawling keep. She bristled her silver coat and black tail, beeping a warning at them not to come any closer. They ignored her, though the woman gave her a brief, uneasy flick of her heavily kohl-rimmed black eyes.

“May I help you, Señoras y Señoras?” asked Claudia. The tall woman with the grey skeins in her long dark hair was a senior Palace servant and Montse’s friend. Montse had slipped her handlers to trail after her as she went about her morning duties, as she liked to do. “These are servant hallways. No places for noble folk such as yourselves.”

The shorter of the two men was the first to have spoken. Unlike the rest of the male Trebs, his face was clean-shaven. His jaw was as square as a door. He looked to Montse as if he ground his teeth a lot.

“Her Highness is here,” he observed in a reasonable tone. His Spañol was good, despite the accent.

“The Infanta lives in the Palace, my lord, and goes where she will.”

As if by chance, Claudia had placed herself between Montse and the interlopers. Though more puzzled by their appearance than anything else, Montse hurried to scoop up Mistral and huddle the creature against the front of her linen smock—white that morning, grubby already. Making sure to support her long-backed friend’s hindquarters with one cupped hand, of course. She didn’t want to injure the ferret.

“We have resided here for months as we pressed the Emperor for answers to our suit,” the noblewoman among the three said, with haughtiness unusual even for a grandeza. Montse decided she didn’t like her. “Thus we live here too. And as noble priests of Trebizon and emissaries of the Basileus, we go where we want as well.”

“Not in El Palacio de las Luciérnagas,” Claudia said, putting a touch of steel in her voice. “Here, allow me to call the Prince’s guards. They can escort you to more . . . congenial surroundings.”

“Please,” the clean-shaven man said. “Our business is with the child.”

“No,” Claudia said.

Things got terrible with a speed that almost choked Montserrat.

The Trebizon lady slapped Claudia across the face. She was almost as tall, even leaving out the hat, and, as far as Montse could tell from her elaborate layers of robes, was as slender as her friend was. The unexpected blow rocked Claudia’s head around.

Without hesitation Claudia spun back and punched the noblewoman in the face. She was strong from a lifetime of hard work, and, having grown up on the waterfront of La Merced, the great La Canal seaport sprawled at the foot of the promontory on which the Palace stood, she knew how to hit. The Trebizonesa reeled back against the wall.

She recovered instantly. From somewhere in her outlandish swaddling she snatched out a stiletto and stabbed Claudia beneath the right breast through her white cotton blouse. The servingwoman froze for a moment, then stepped back. But instead of locking up or moaning in pain, much less collapsing from the wound, as a horrified Montse expected her to, Claudia tried to launch another punch at the priestess’s face.

The bearded man grabbed her arm from behind, stopping her swing. He clutched for a hold on her left arm as well.

From the hornface-leather belt she wore to cinch up her long brown skirt and to carry such items as her duties might require, Claudia drew a butcher knife with her free left hand. She plunged it down and back. The bearded man gasped and then squealed as it sank to the handle into his stomach.

He bent over himself, groaning. But he didn’t let go of Claudia’s wrist. The noblewoman stepped in to stab Claudia again and again like a bird pecking—so fast Montse lost count of the thrusts.

She became aware she was screaming at them to stop hurting her friend. She had backed against the wall opposite the mouth of the side passage through which the three intruders had entered.

Claudia’s blouse was a sodden red mass. She caught Montse’s eye and mouthed, “Run!” Her teeth were individually outlined in red; Montse knew she’d dream about the sight as long as she managed to stay alive.

Montse saw the life leave her friend’s eyes. Claudia’s head lolled to the side. She sagged. The bearded man, still mewling in agony, released her suddenly dead weight to puddle on the floor in blood and sadness.

The clean-shaven man approached Montse. He held out a big, square hand. “Come with us now, little girl. We won’t hurt you.”

“Like the way you didn’t hurt my friend?” Montse shouted, more in rage than grief. She turned to bolt for a secret passage—the Palace was honeycombed with them—to her left.

Instead, she turned straight into a tall man wearing a slashed-velvet doublet and short pantaloons over leggings, all in black. He gathered her against him, turned her, and pinned her against leanly muscular legs.

From her eye’s corner she saw that the entry to the secret passage, which was disguised as a lamp alcove, stood open. Some servant sold us out! she thought, sickened. One of my friends.

She opened her mouth to scream for help—not a natural action for her, or she’d have started earlier. Her captor clapped a hand over her mouth.

“What have you idiots done?” he demanded “Everything depends on avoiding violence.”

The woman, whose dark robes were almost as blood-soaked as Claudia’s blouse but showed it less, brandished the slim dagger and spat something in her native tongue.

“She’s a valued servant and friend to the little princess, here,” Dragos responded in Spañol. “Her employer, Prince Heriberto, will resent her murder here in his own palace.”

“They were going to resent the girl’s abduction, anyway,” the beardless man said. “And she was impudent to Lady Paraskeve.”

Montse had witnessed violence before. She’d attended tournaments, never by her own choice. She’d seen men and women injured, even watched an elderly knight die by accident during a recent tourney. But she’d never seen a friend die before. Nor had she experienced violence directed against her.

Being grabbed by a stranger shocked her. It felt like a violation. For a brief spell, it caused her to freeze in panic.

But she recovered fast and bit the muffling hand. Hard.

“Ow,” her captor said, but mildly. “I deserved that, for not expecting it.”

He shifted his hand to keep her quiet but removing her chance to chomp him again. Turning, he shoved her toward one of a pair of human nosehorns, locals by their look and dress, who had emerged from the not-so-secret passage.

“Mind her teeth, Diego. They’re sharp. And she’s fast and feisty.”

Diego’s hand was big enough that Montse’s mouth could get no purchase. She kicked back furiously with a bare heel.

“Ow! My shin!”

The murderous Lady Paraskeve had put away her stiletto. Now she pointed toward Mistral, whose fur bristled and who was hissing furiously and writhing in Montse’s hands. “Take that filthy animal away from her and kill it.”

“No!” Montse tried to yell. But of course she only produced a muffled squeal of outrage.

Helplessness, she found, made her all the madder. But it did no good against Diego’s strength and apparently durable shins.

“No,” the man who had seized Montse said. He was tall, perhaps poor Claudia’s height, slender as the Taliano rapier he wore at his fashionably clad waist, with neatly trimmed grey hair and beard. Montse had seen him at court the last week or so; several women and a couple of men, not all servants, had commented what a fine figure he cut.

He continued in Griego. Which Montse couldn’t understand a word of.

“You dare to contradict me?” Paraskeve snapped back in Spañol. “Who do you think you are, Dragos?”

“I think I am a specialist hired by your masters to keep you from making a total botch of this,” Dragos said, his voice still level. “At which I’ve failed—which means you need me all the more just to get out of this Palace alive, much less out of the Empire with your skins still attached. And I think I’m a man who has taken measures—including certain compacts with your masters—to safeguard against treachery on your parts.”

“Leave be, Paraskeve,” the clean-shaven man said. “Can you walk, friend Stamatios?”

“I’m fine.” Stamatios gave away his words as a lie by the way he sobbed them, hunched over to one side with a hand pressed to his blood-pouring belly. “I can walk.”

Blood drooled from his lips and matted his beard when he spoke. Montse found she didn’t find that horrifying. She wanted him to die.

He took a step. His knees promptly folded. He only kept himself from going to the floor by falling against the dank stone wall.

“We have to leave him,” Dragos said. “You—kill yourself. You’ll slow us down, and we can’t afford that. If we’re caught, not only is Prince Heri likely to forget the Creators’ Law against torture but, worse, our masters will be very vexed with us. And they seldom remember that Law to start with.”

“You can’t—” bearded Stamatios began. Seeing the set of Dragos’s face, he looked to his male comrade. “Please, Akakios. Tell him he can’t—”

Dragos stepped purposefully up to Stamatios as the wounded man shoved himself more or less upright. He brought the heel of his right palm savagely up against the underside of a bearded chin. Stamatios’s jaws clacked together with a sound that made Montse wince despite herself.

The priest jerked. His black eyes shot wide open. Dragos pinned Stamatios against the wall by both arms as his mouth worked frantically, as if trying to take bites of the air. His body shuddered as if trying to shake itself to pieces.

His face turned a shade of forge-heated-iron red Montse had never seen on human skin before. His body shook to a spasm so fierce Montse expected bones to snap, then went as limp as Claudia had.

Dragos let go his arms and stood back. Stamatios plopped onto his face on the stone.

He’s dead, Montse thought. For some reason it shocked her almost more than seeing her friend die. I wanted him that way. I’m glad. Why does it feel so bad?

Nausea welled up from her stomach. She willed herself to puke. It’ll serve this lout right for putting his dirty hand over my mouth! But she sadly failed to vomit.

Dragos turned away from the corpse and straightened the discreetly frilled cuffs of his black silk blouse.

“Those poison teeth your masters insisted you all be tricked out with do have their uses,” he purred to the two surviving emissaries. “Come on. We’ve wasted enough time.”

He nodded to Diego and his companion, who was out of Montse’s line of sight but whose presence she sensed looming nearby.

“Don’t be more afraid than you can help, little princess,” Dragos told her as the hand was removed from her mouth. She sucked in a deep breath to scream—and her vision was obscured by enveloping blackness.

Her heart almost burst from her chest in terror. I’m blind! I can’t breathe! But then she realized a heavy bag had been pulled over her head by the feel of its coarse cloth on her nose.

“We need to deliver you alive and well,” she heard Dragos’s smooth baritone, “if we want to stay that way ourselves. Remember that, as the herbs in that bag help you to peacefully sleep.”

Herbs? she thought. She found it hard to remember what the word meant. Her head spun.

Blackness swallowed her whole.

“Young woman, your father is damned!”

Air, forest swells, evening light, and emotions flooded Montserrat’s world as the hood was yanked from her head. She was racked in turns by rage, grief, fear, confusion, and rage again. All battled furiously for the privilege of propelling the first word from her mouth when she at last confronted her captors.

But what popped out was, “What?”

“The Emperor is damned!” the woman who had murdered Claudia shouted, her face mere centimeters from Montse’s. Her face was painted almost white, with rouge spots on the cheeks. They made her pores look huge. “He’s condemned himself! Not only by the unpardonable insult he’s offered our Basileus by refusing to even answer our suit for your sister to wed our Crown Prince, but now he’s thwarted the will of the Creators themselves!”

“What are you on about?” Montse said. She asked the question is Spañol, which was what the woman asked it in. But despite the circumstances, she felt pride in translating an Anglysh phrase she’d read on the fly. She read a lot of books and treatises in Anglysh. She loved everything to do with the island Kingdom almost as much as Prince Heriberto, ruler of the Principality of the Tyrant’s Jaw and landlord of the Firefly Palace, did.

“She means we’ve just learned that your father’s army has met and defeated the Grey Angel Crusade in western Francia, near County Providence,” the man called Dragos said. “He saw Raguel off quite smartly, it seems, and with the Grey Angel’s passing, the Horde broke apart like a melon dropped on flagstones.”

The murderer turned her white rage-twisted face aside to screech at him, “Blasphemer! To make light of the death of one of the Creator’s own servants!”

“Which of us is the blasphemer, Paraskeve,” Dragos murmured, quite unfazed. “Me, or you for imagining a Grey Angel could be killed so readily?”

Producing a silken kerchief from his sleeve, he dabbed her spittle from his grey beard and the sun-browned skin of his cheek.

Montse had her bearings now. She had been hauled up and unmasked in a clearing in the forests that covered the hills inland from Firefly Palace and the great Channel port of La Merced. Insects buzzed and trilled in the trees around and above and in the fragrant ferns underfoot. A flying squirrel glided from limb to limb beyond the madwoman’s right shoulder to take a nosehorn-fly the size of a big man’s thumb in flight.

It’s either the one where we took Melodía and Pilar when Claudia helped me break my sister out of the Palace, she thought, or one a lot like it. Must be a popular stop for people running away from there. A pair of carriages with curtained windows and a gaggle of horses stood at the base of a stand of tall pine trees whose slim yellow boles rose ten meters before branching out.

Then memory of seeing Claudia brutally killed right in front of her twisted her stomach and clouded her eyes with tears.

“You monsters!” she shrieked. “Prince Harry will have all your heads for this! You killed my friend.”

“Did we?” asked a woman with wild hair and haunted eyes. Montse had seen her with the others in the Palace once or twice. Apparently her kidnappers had rendezvoused with the rest of the Trebizon emissaries.

Montse studied her face. It was less clownishly painted than Paraskeve’s. I have to remember everything, she told herself firmly. It will help me get away. I don’t know how or when it’ll help, but I know I need to do that.

“A nobody, Tasoula,” Paraskeve said. “A servant.”

“She did kill Stamatios,” the leader—Akakios, Montse remembered—said in his deep, rich voice.

“No, that greybeard with you did! And good riddance!”

“Please,” Dragos said. “You make me sound so old. Consider my vanity.”

“And where’s Misti?” Montse yelped, suddenly remembering her other friend who had been with her.

“Safe,” said Dragos. He held up a hemp sack that was squirming and kicking. “She bites, so we had to bag her, too. Like you, she has very sharp teeth.”

Montse reached out, surprised to discover her hands weren’t bound. She took the bag carefully, near the top. She could hear Silver Mistral chittering in muffled rage. She opened the drawstring, reached in carefully, and, as luck had it, found the soft-furred nape of Misti’s neck before the ferret sank those teeth into her. She pinched loose skin, gently yet firmly, and lifted her friend out of the bag. Misti’s struggles stopped at once and she relaxed, as ferrets did when you picked them up that way.

“I’m here, sweetheart,” Montse told her. “I won’t let the bad people hurt you.”

“As to that,” Dragos said, “I had to remind the others we’d agreed to keep her unharmed for you, Princess. When the Prince of Tyrant’s Jaw takes my head, you will remember to ask him to make sure the headsman’s axe is keen, I trust.”

On being reunited with her beloved human, Mistral quickly calmed down. Scooping a hand beneath her fuzzy butt to support her, Montse curled the long, slender body and clutched the ferret to her chest.

She glared at her captors. All the ones she was used to seeing lurking about the Palace were there, minus the dead one, of course. The two survivors—three, if you counted Dragos, who didn’t seem to be Trebizonés himself, or five if you included the two local bravos—had been joined by three men and the unkempt woman. The Trebizon emissaries all had dark skin—Montse could tell from Paraskeve’s hands—as well as black eyes and hair. None of which made them stand out in Spaña, though to Montse’s eye they looked somehow different from her paisanos, even the highborn ones.

“You’re evil,” she said, with as much contempt as she could muster. She wasn’t used to mustering much, really. She knew the adults around her—especially those her father put in charge of caring for her and keeping her under a modicum of control—were mostly stupider than she was. But that didn’t really merit contempt, as far as she was concerned. Pity, more, when she thought about it. But now she made shift—as the Anglysh romances she loved would put it—as best she could. “Also, you’re all crazy, if you think I’m going to be all sad to learn my daddy won a battle!”

“Not all of us think that,” Dragos said. “If it makes you feel better, we’ve also learned your sister Melodía apparently survived and has apparently reconciled with your father.”

That brought Montse up short. It did make her feel better. Of course! She’d been desperately worried since Melodía had been arrested on phony charges of plotting against her father. They’d redoubled when word came that the feared-but-improbable Grey Angel Crusade had actually broken out in Providence, where she had gone. It was wonderful news.

But it didn’t stop Montse from being madder than she’d ever been in her life.

She pondered. She didn’t often use bad words, believing that doing so was just sloppy and lazy. She didn’t like sloppiness or laziness. She admired people who did things.

But sometimes . . . she told herself. And drawing in a deep breath, yelled:

“Fuck you!” And turned and ran for the woods as fast as she could.

One of the Spañol hirelings caught her within a dozen paces, of course. He tucked her under one arm and carried her, kicking and squalling, waving Mistral in one hand and trying determinedly to bite, to one of the waiting carriages.

She still felt good for trying. I didn’t make it this time, she thought. But I won’t give up.

She decided the more her captors dismissed her as a hysterical child, the better. So she burst into tears.

It distressed her, though, how easy she found that.

And in a few sobbing breaths, it was no longer an act.

Copyright © 2017 by Victor Milán

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

From Morgan Llywelyn, the bestselling author of Lion of Ireland and the Irish Century series, comes Drop By Dropher first near-future science fiction thriller where technology fails and a small town struggles to survive global catastrophe.

From Morgan Llywelyn, the bestselling author of Lion of Ireland and the Irish Century series, comes Drop By Dropher first near-future science fiction thriller where technology fails and a small town struggles to survive global catastrophe. Humankind ventures further into the galaxy than ever before… and immediately causes an intergalactic incident. In their infinite wisdom, the crew of the exploration vessel Magellan, or as she prefers “Maggie,” decides to bring the alienstructure they just found back to Earth. The only problem? The aliens are awfully fond of that structure.

Humankind ventures further into the galaxy than ever before… and immediately causes an intergalactic incident. In their infinite wisdom, the crew of the exploration vessel Magellan, or as she prefers “Maggie,” decides to bring the alienstructure they just found back to Earth. The only problem? The aliens are awfully fond of that structure. In 1938, death is no longer feared but exploited. Since the discovery of the afterlife, the British Empire has extended its reach into Summerland, a metropolis for the recently deceased. Yet Britain isn’t the only contender for power in this life and the next. The Soviets have spies in Summerland, and the technology to build their own god. When SIS agent Rachel White gets a lead on one of the Soviet moles, blowing the whistle puts her hard-earned career at risk. The spy has friends in high places, and she will have to go rogue to bring him in.

In 1938, death is no longer feared but exploited. Since the discovery of the afterlife, the British Empire has extended its reach into Summerland, a metropolis for the recently deceased. Yet Britain isn’t the only contender for power in this life and the next. The Soviets have spies in Summerland, and the technology to build their own god. When SIS agent Rachel White gets a lead on one of the Soviet moles, blowing the whistle puts her hard-earned career at risk. The spy has friends in high places, and she will have to go rogue to bring him in.

#1:

#1: