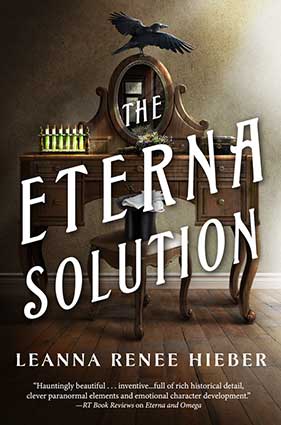

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Eterna Files, a gaslamp fantasy about the quest to find the secret to immortality. The final book in the series, The Eterna Solution, will be available November 14th.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from The Eterna Files, a gaslamp fantasy about the quest to find the secret to immortality. The final book in the series, The Eterna Solution, will be available November 14th.

London, 1882: Queen Victoria appoints Harold Spire of the Metropolitan Police to Special Branch Division Omega. Omega is to secretly investigate paranormal and supernatural events and persons. Spire, a skeptic driven to protect the helpless and see justice done, is the perfect man to lead the department, which employs scholars and scientists, assassins and con men, and a traveling circus. Spire’s chief researcher is Rose Everhart, who believes fervently that there is more to the world than can be seen by mortal eyes.

Their first mission: find the Eterna Compound, which grants immortality. Catastrophe destroyed the hidden laboratory in New York City where Eterna was developed, but the Queen is convinced someone escaped—and has a sample of Eterna.

Also searching for Eterna is an American, Clara Templeton, who helped start the project after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln nearly destroyed her nation. Haunted by the ghost of her beloved, she is determined that the Eterna Compound—and the immortality it will convey—will be controlled by the United States, not Great Britain.

PROLOGUE

The White House, April 16, 1865

The sanity of a bloodied nation hung by a precarious thread. Hundreds of thousands of bodies rotted in mass graves. Mountains of arms and legs lay just beneath the earth in countless pits of appendages. Thousands of young men had been torn into wingless birds, stunned, harrowed, and half whole. No one had gone untouched by the war; everyone was haunted.

A gunshot in a theater tipped the straining scales and the nation’s battered, broken heart faltered and stopped.

This was the world in which twelve-year-old Clara Templeton grieved. She wept for her land with the kind of passion only a young, gifted sensitive could offer. When she was called to the side of the first lady, she did not hesitate.

Clad in a black taffeta mourning gown, Clara stood in a dimly candlelit hallway outside the first lady’s rooms, awaiting admittance alongside her guardian, Congressman Rupert Bishop, aged twenty-five—though his prematurely silver hair gave one pause as to his age. He’d been silver-haired as long as she’d known him. When she’d asked about it with a child’s tactlessness, he’d simply responded with a wink and a smile: “It’s the fault of the ghosts.” Soon after, Bishop took her to her first séance and Clara began to understand just how dangerous the thrall of ghosts could be.…

A red-eyed maid opened the door and gestured them in.

Inside the small but well-appointed room, a low fire mitigated a cool draft and cast most of the light in the room. Mary Todd Lincoln sat on a chair in the shadows, staring out a small window, her bell-sleeved, black crepe dress spilling out in all directions. Only the ticking of a fine clock on the mantel and the occasional sniff from the weeping maid broke the silence. The congressman beckoned Clara forward, into the firelight. Her step creaked upon the floorboards as her petite body cast a long shadow behind her.

Finally the first lady spoke in a quiet tremor. “Do you know why I called you here, Miss Templeton?”

“I’ve a supposition,” Clara replied quietly, nervously moving forward another step. “But first, Mrs. Lincoln, my deepest sympathies—”

“When your guardian here first brought you to visit the White House two years ago, you ran up to me, a perfect stranger, and gave me an embrace from my William. My dead William.”

“Yes, Mrs. Lincoln,” Clara murmured, “I remember—”

“I need you now, Miss Templeton,” the first lady began with a slightly wild look in her eyes, “to give me an embrace from my dead husband.”

Alarmed, Clara looked at Bishop, her eyes wide. The tall, elegantly handsome man lifted a calming, gloved hand and Clara attempted to gather herself

“I … well,” she stammered, “I’m unsure my gifts can work on command, Mrs.—”

“Try!” the grieving widow wailed, turning to face the girl, her face drawn and hollowed. Clara rushed over and fell to her knees beside the first lady, removing her kid gloves to take Mary’s shaking, bare hands into hers.

“I know that he is with you,” Clara murmured, tears falling from her bright green-gold eyes. “The president is with all who mourn him—”

“Prove it,” Mary Todd murmured. She snapped her head toward the door. “Rupert. You’re a spiritualist, have you not trained Miss Templeton since she became your ward?”

“Only charlatans cue up the dead precisely when the grieving want them, Mary, you know that,” Bishop said gently. “And this is far too vulnerable a time to try.” He shivered suddenly. “Too many things want in. We risk inviting malevolence, not comfort.”

“No one should ever have to suffer what I have—” the first lady choked out.

“No, they shouldn’t,” Clara replied. “Never.”

“The country can bear no more,” Bishop added quietly, his fine black mourning coat making him almost invisible in the shadows by the door. “We must guard against the basest evils grasping for purchase—”

“What could be more evil than what I have endured?” the first lady exclaimed.

The last two years had taught Clara that Rupert Bishop coddled no one, even the grieving. She spoke before he could offer another example of his oft-sobering perspective. “Such a powerful seat needs protection,” Clara exclaimed, squeezing the widow’s shaking hands with innocent, sure strength. “Such a man should never have fallen. He deserved to have been made immortal!”

“Why … yes, child!” Mary Lincoln exclaimed, a sudden light in her eyes. “Do we not have resources, researchers, scientists, theorists? Should we not have granted a man like the president eternal protection while he bore the nation on his shoulders? My dear Congressman Bishop…”

The small woman rose to her feet and began to pace the room, skirts swishing and sweeping with renewed determination.

“I charge you,” she said, bright gaze fastened on Bishop. “If you’ll not bring my husband back to me in spirit or form, then you must do this. Take Clara’s idea. For this bled-dry country. For the seat cloaked in immense power. Do this, Congressman, so no other wife in this dreadful house might go through such agony again.…”

“Do what, Mary?” he pressed.

She stared at him with steely ferocity. “Find a cure for death.”

Seventeen Years Later, New York City, 1882

“It was born of good intentions,” Clara insisted in a choking murmur.

She sat on a bench in Central Park on a mild June day, beneath a willow tree, looking out over the southeastern pond. She could not move. Her breath was shallow against the double stays of corset and buttoned bodice; soft ivory lace and muslin ruffles trembled around her throat. Tendrils of dark blond hair, blown free from braids beneath a fanciful straw feathered hat, tickled around her streaming eyes. Her world was again cracking open.

“Wake up,” she heard a voice calling. “Wake up.” It was not a human voice but that of some ancient, cosmic force.

She had known there was something different about her since the age of nine, since she’d awakened in the middle of the night to see a wild-haired woman in a cloak sitting at the foot of her bed.

“You’re special,” was all the woman said before vanishing.

The next day, Clara’s father, a prominent doctor to Washington lawmakers, died of tuberculosis. Her mother soon followed. They were buried in a Greenwood Cemetery mausoleum in their native Brooklyn. Clara was the marble sepulcher’s most frequent haunt. The Templetons’ will ensured that Clara would be educated at fine institutions and looked after by prominent figures.

Rupert Bishop, then a talented young New York lawyer, frequented the same Washington and spiritualist circles as the Templetons. A beloved family friend, he stepped in to graciously provide for the girl left behind. Bitterly estranged from their Southern families after the war, the Templetons hoped Clara’s manifest spiritual talents would blossom under Bishop’s care and guidance. She indeed flourished, until her gifts turned physically dangerous and had to be carefully monitored.

The visitor returned the night Bishop brought Clara to the White House the first time; Clara saw the creature watching her from the shadows. She had not seen the strange herald since, not even after that fateful second encounter with the first lady, a meeting that had set an unlikely destiny in motion.

Paperwork left on the slain president’s desk established a “Secret Service” to investigate counterfeit currency. A tiny cabal, headed by Bishop, supposed the service might also, in some unnamed office, investigate immortality. Bishop assembled a team of occultists, mystics, and chemists and set them to work in a secret location.

Once Clara completed finishing school, Bishop gave her a key to a nondescript office on Pearl Street in downtown Manhattan. A county clerk’s record office on the first floor served as a front. Clara’s offices—and those of the colleagues she and Bishop hired—took up the top floor. Congressman Bishop became Senator Bishop. A quiet era of investigation and theorizing followed.

In 1880, Eterna theorist Louis Dupris secretly told Clara that he’d made a breakthrough in localized magic. The world had suddenly seemed full of possibility. But now …

The Eterna Compound had been born out of grief. At this moment Clara wondered if it should never have been born at all, for now it bore grief of its own.

“Something’s wrong,” Clara murmured, wanting to cry but feeling wholly paralyzed. “I can feel it.…” All of Clara that had ever been could feel it; a love torn from her like layers of skin.

Before her eyes, in layers of concentric circles stretching out like mirrors reflecting mirrors in dizzying multiplication, she saw lives. Her lives, those she’d had before. She was twenty-nine years old … with a soul a thousand years older.

Pried open in a painful awakening, she knew her life was far more than the boundaries and limitations of her current flesh, but at present she felt the pain of all those centuries all at once, things done and undone. The sheer, heavy press of it all was staggering.

A mockingbird alighted on a branch above Clara’s head. It squawked and stared at her, then made the sounds of a police whistle, a bicycle bell, and some roaring, whooshing thing: the sound of something tearing.

And then there was a woman next to her. The visitor.

Though she couldn’t turn her head, in her peripheral vision Clara saw skirts, gloves, and long hair that was scandalously unbound. The presence of the visitor confirmed what she was feeling; something terrible was happening. Clara tried to move again, to fight the gravity lashing her to the bench, wishing tears, something, anything could be set free.

“What is it this time?” Clara gasped.

“Hello, Clara,” the visitor said quietly. One didn’t mistake an ordinary person for the visitor, for it brought with it the weight of time itself. “It’s been awhile.” The visitor smoothed the skirts of its long, plain, black, uniform-like dress, something a boarding school girl might wear. “Have you been waiting?” the visitor asked.

“I’m not one who likes waiting,” Clara replied.

“That’s why I trust you,” the visitor said, pleasure in its voice. “I last saw you when you impetuously gave the first lady an embrace from her dead son.”

The mockingbird gave a raucous trill from the limb above them. The woman adjusted what Clara thought was a hat—she still couldn’t get a good look. The mockingbird had flown across the path and alighted on a limb at her eye line, trilling accompaniment to their conversation.

“You presage terrible things but I never know what,” Clara growled.

“You’ve always been gifted,” the visitor replied. “Sensitive.”

“And we see what good sensitivity has done me.” Clara choked out her words. “I’m a freak of nature. My ‘fits’ render any hope I might have had for a normal life or a place in society laughable. I curse my gifts for all the misfortune they bring.” Embarrassing, traumatic memories paraded through her mind, her past lives staring on in pity. Clara hated pity. Perhaps it was best, then, that the visitor had none.

“Don’t be ungrateful, child,” the visitor chided. “You’ve two friends in a world of loneliness, you had a lover when many never know such pleasure, you’ve worked when hordes seek pay, you’ve had a guardian who dotes on you when countless orphans have no one, and you’ve money and a fine house in a city that denies both to thousands of its denizens.”

Clara wanted to lash out at the creature. But it was right, which only sharpened her pain.

“Something terrible has happened, hasn’t it? To the Eterna team?” she whispered, her throat raw as if from screaming even though she had loosed no such sound. “To my Louis? My love is among them.…”

An amulet of protection, tucked beneath her corset stays, was a knot against her shaking breaths. The amulet had been given to her by Louis, an item charged and blessed by his mother. Clara never felt she had the right to it, and now, he, who needed protection, lacked it

“I am very sorry for your loss,” the visitor said solemnly.

“I must go,” Clara insisted, trying to fight free but failing. “Maybe I can help the team—”

The visitor held up a hand. “It’s no use. They’re gone.”

“Why can’t you stop terrible things if you’re aware of them?” Clara demanded. “Why can’t I?”

“Not in our skill set,” the visitor replied. “You’ve taken too much ownership of something that is not your responsibility, Templeton. What is your responsibility, is to—”

“‘Wake up?’ Yes, I hear it, on the wind. In my bones. What does it mean?”

The woman gestured before her, to Clara’s iterations. “You see the lives, don’t you?”

“Yes.” Clara swallowed hard. “Do you?”

“Of course I do,” the visitor replied. “I’m here to tell you that a great storm is coming. It will break across two continents; two great cities, the hearts of empires. Your team is gone and storms are coming. Weather them, find special souls and shield them. Second-guess your enemy. Find the missing link between the lives you see. Do this for yourself. And for your country.”

Clara snorted bitterly. “Do I hear patriotism?”

The visitor shook its head. “I owe allegiance to no land.”

“Then what are you here for?” Clara begged.

The visitor’s voice grew warm. “I care about certain people.”

“Why me?”

“Show me why you, Templeton,” the visitor proclaimed. “You’re at the center of the storm. Be worthy of the squall.”

The mockingbird made the strange, roaring sound again and the woman was gone.

Clara’s hands shook. The people she had been in her many lives turned and looked at her, male, female, all with certain similar qualities that she recognized as uniquely hers. Curiosity. Hunger. Restlessness. Intensity. Independence. A desperate desire for noble purpose. And lonely.

She was awake. But Eterna had died, taking with it the lover no one knew she had.

CHAPTER ONE

London, 1882

Harold Spire had been pacing until first light, crawling out of his skin to close his God-forsaken case. The moment the tentative sun poked over the chimney tops of Lambeth—though it did not successfully permeate London’s sooty haze—he raced out the door to meet his appointed contact.

Conveniently, there was a fine black hansom just outside his door. Spire shouted his destination at the driver as he threw open the door and launched himself into the carriage. He was startled to find that the cab already had an occupant: a short, balding man, immaculately but distinctly dressed; as one might expect of a royal footman.

“Hello, Mr. Spire,” the man said calmly.

Spire’s stomach dropped; his right hand hovered over his left wrist, where he kept a small, sharp knife in a simple cuff. Surely this was one of Tourney’s henchmen; the villain was well connected and would do anything to save his desperate hide.

“Do not be alarmed, sir,” the stranger said. “We are en route to Buckingham Palace on orders of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.”

“Is there a problem?” Spire asked, maintaining a calm tone, relaxing his hand but offering up a silent prayer to whatever God was decent and good that the queen would not have interceded on the wretch’s behalf.…

“No, sir. You are being considered for an appointment. I can say nothing more.”

“An … appointment.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m afraid I cannot attend to this great honor at present, sir.”

The man arched a preened brow. “Beg your pardon?”

“With all due respect,” Spire continued, not bothering to hide the earnest desperation he felt, “I am a policeman at a critical juncture, awaiting receipt of vital material without which a vicious criminal might walk free—”

“And what shall I tell Her Majesty? That you’re too busy for her?”

Spire set his jaw, looking anxiously out the window, seeing that they were heading in the opposite direction from where he needed to be at precisely seven. “Please tell Her Majesty that I’m about to stop a ring of child murderers and resurrectionists. Burkes and Hares. Body snatchers—”

“That will have to wait. Mere police work does not come before Her Majesty.”

“I think highly enough of Her Majesty to think she’d deem this important.”

“I am under orders to take you to the palace regardless of prevarication—”

“I wouldn’t dare lie about a thing like this!”

“Once Her Majesty has determined your suitability, you’ll be returned to your duties.”

“You’ll have to give the empress my sincere regrets. She may be able to live with one more child dead in her realm but I, sir, cannot.”

With that, Spire opened the door of the moving carriage and cast himself onto flagstones slick with the foul mixture of the London streets. His heel turned slightly under him and he came down painfully; his elbow jarred against stone and his forearm cut against the brace that held his knife sheath. He jumped to his feet and ran—with a slight limp—veering onto a bridge across the busy, teeming, brown Thames and onward to a life-or-death rendezvous.

He’d likely be arrested for his evasion, but his conscience was utterly clear.

# # #

Spire’s right hand hovered over his left forearm as he entered the damp brick alley, which was lit sporadically by gas jets whose light was dim behind blackened lantern glass. Even though the world was brightening with the gray of morning, sunlight didn’t penetrate into these drear, winding halls of sooty brick, London having its labyrinthine qualities. He made his tread soundless on the cobblestones, his eyes aware of every shadow and shape, his ears alert, his nostrils flared.

While he doubted his informant was dangerous—it was all bookkeeping, really, he imagined the source was a bank clerk or the like—what the ledgers revealed was something else entirely. The proof itself was dangerous and many men would kill with far less provocation. If “Gazelle” proved trustworthy, Spire would recruit the man for his department.

He palmed the key Gazelle had left in the drop location at Cleopatra’s Needle. If all had gone according to plan, Gazelle would have left enough evidence at this bookstore to prove without a shadow of a doubt that Francis Tourney was bankrupting charitable societies in a speculation racket that would make any betting man blush. That he was also involved in a child-trafficking ring of both living and dead young bodies was harder to prove, but far more damning.

The key opened the rear-alley door of the bookshop. A small lantern was lit somewhere within, casting a wan yellow light over stacks of spines. Spire knocked on the wooden door frame: three taps, a pause, and two more.

A quiet rap in response, from somewhere within the maze of books, confirmed that his informant was waiting. Spire edged his way through boxes and stacks—one stray limb could cause the whole precarious haphazard system to tumble—toward the source of the light.

He turned a corner of books and stopped dead in his tracks. There sat a woman who had gotten him into a good bit of trouble—the prime minister’s best-kept secret, his bookkeeper, one Miss Rose Everhart. Poised as ever, seated at a long wooden table; the lit lantern cast her scowl of concentration into sharp relief as layered bell sleeves spilled over a stack of thin spines. One ledger lay, open, under her hand; she ran ungloved fingertips over the pages.

She wasn’t stunning, but unique; her full mouth, set now in a frown, gave her a gravitas offset by the few loose brown curls around her cheeks, an almost whimsical contrast to her fastidious expression. When she looked up at Spire, the intensity and razor-sharp focus of her large blue eyes made her intriguing, magnetic.

“You’re surprised to see a woman,” she said. It was not a question.

“Yes.” Spire spoke very carefully. “Especially one I recognize.” At this, she smiled, a prim, self-satisfied smile. “You made quite an impression, Miss Everhart. A cloaked female figure glimpsed wandering the halls of Parliament, only to disappear into a wall? I didn’t buy the story that you were a specter.”

“The too-curious Westminster policeman. So we meet again,” she said with an edge. “The eager dog sniffing out a fox. My employers, who were granting me the easiest access to my job while hoping to avoid any national outcry, were not fond of you. And I confess, nor was I. It was bad enough to have to sneak about, then to be thought suspect for it when I am a patriot? Horrible.”

“Yes, I was quite chastised about that by your superior, Lord Black,” Spire muttered, “so you needn’t pile on.” He wondered with sudden fear if that’s why the queen wished to see him: more scolding. Spire’s purview was Westminster and its immediate environs. When he’d stumbled upon Miss Everhart, he’d merely been doing his job. Tourney’s speculation ring involved members of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, so it was perhaps not surprising that Spire had thought that the prime minister’s bookkeeper had access others did not.

At the mention of Lord Black, Miss Everhart smiled and warmed. She stood suddenly, as if on ceremony, gesturing for Spire to sit at the bench opposite. While she was primly buttoned in dour blues and grays, her skirts and bodice were tailored in unique lines and accented with the occasional bauble that made Spire think a subtle bohemian lived somewhere deep beneath her proper corset laces.

“We have enough on the racketeering for a compelling case,” she said, handing several ledgers across the table.

“Good,” he said, nodding.

“But it’s this that will deliver the decisive blow,” she murmured, and shuddered. She passed him a narrow, thin black book that she didn’t seem eager to touch. The cover said, “Registry.”

“What’s this? Did you collect this from the banks?”

“No. From Tourney’s study.” At Spire’s raised eyebrow, Miss Everhart clarified, “After I showed him the numbers, Lord Black arranged for Sir Tourney to attend some sort of speculators’ gala. Black stamped a warrant and found this.”

“Himself?” Spire asked, incredulous.

“Lord Black had been feted at the Tourney estate, so sending him in was the most efficient. He knew to look for anything out of the ordinary. And this is hardly ordinary.”

Shocked by a lord’s unorthodox method but impressed by the man’s initiative, Spire opened the book. Small, dark marks and round smudges marched down the pages in boxes made up of thin graphite lines. A few letters—initials, Spire guessed—were penciled above each dot.

On one side of the page, the dots were dark red. On the other side, the small marks were black. At the top of each page was a single large letter: “L” above the red marks and “D” above the black.

Horror dawned, slow and sick, as Spire stared at the lines of dots and initials. Dots the size of a child’s fingertip.

“Living.” Spire’s finger hovered over the “L.”

Then he moved to the “D.” “Deceased”

Oh, God. They were children’s fingerprints. Swabbed in their blood. Or, if their bodies had been stolen when dead, their fingers dipped in ink and pressed to the page.

A registry of stolen children.

Used for God knows what.

“I…” Spire stared at Miss Everhart, whose face was unreadable. “I’m sorry you had to see this.”

Her jaw tensed, pursed lips pressed thinner. “I am thirty and unmarried. I doubt I’ll ever have children, so I do whatever I can. I owe it to those poor children not to flinch.”

Spire nodded. He hadn’t thought to place any women assets in his police force. But women could keep secrets, tell lies, deceive, and connive with an aptitude that frightened him. Women made bloody good spies. He knew that well enough.

Spire rose, sliding the ledger, breakdown, and “registry” into his briefcase. “Thank you, Miss Everhart. Please give Lord Black my regards, I was unaware he was involved. I’m not wasting any time on the arrest.”

“I didn’t imagine you would.” Everhart rose and wove expertly through the labyrinth of books. As she disappeared, she called back to him. “Go on. I’ll alert your squadron. I doubt you should go there alone.”

He stared after her a moment, resentful of initiative taken without his orders … but it would save him valuable time.

# # #

Spire and his squad descended upon the decadent Tourney estate; a hideous, sprawling mansion faced in ostentatious pink marble, hoarding a generous swath of land in North London.

His best men at his side, Stuart Grange and Gregory Phyfe, Spire stormed Tourney’s front door, blowing past a startled footman.

The despicable creature was having breakfast in a fine parlor. The son of a Marquis, descended of a withering line, seemed quite shocked to see the police; his surprised expression validated Spire’s existence.

Spire was tempted to strike the man across the jaw on principle but became distracted by the thin maid, in a tattered black dress and a besmeared white linen apron, who cowered in the corner of the parlor. Entirely ignored by the rest of the force, she was shaking, unable to look anyone in the eye. Her condition was a stark contrast to her fine surroundings, which valued possessions higher than humanity.…

Shaking his head, Spire instructed his colleagues to secure Tourney in the wagon.

“I’ve all kinds of connections,” the bloated, balding man cried as he was dragged away. “Would you like me to list the names of the powerful who will help me?”

“I think you’re in too deep for anyone but the devil to come to your aid, Mr. Tourney,” Spire called as the door was shut between them. Silence fell and he turned to the woman in the corner.

At his approach, the gaunt, frail maid began murmuring through cracked lips, “Please, please, please.” She lifted a bony arm and the cuff of her uniform slid back, revealing a grisly series of scars on her arm. Burns. Signs of binding and torture.

“Please what, Miss?” Spire asked gently, not touching her.

“S—secret door … Get them … out.…” She pointed at the opposite wall.

A chill went down Spire’s spine. He studied the wall for a long time before noticing the line in the carved wooden paneling. Crossing the room, he ran his hand along the molding, pressing until something gave. The hidden door swung open and a horrific stench met his nostrils.

The maid loosed a wretched noise and sunk to her knees, rocking back and forth. Spire raised his voice, calling to his partner and friend, a stalwart man who played all things carefully and whom Spire trusted implicitly, “Grange, I think there may be a … situation down here.”

Without waiting for a reply, Spire was through the door and descending a brick stairwell, fumbling in his pocket for a box of matches. A lantern hung at the base of the stair; he lit the wick and set it back upon the crook. The flame, magnified by mirrors, cast a wan light over the small, windowless brick room.

It was everything Spire could do to keep from screaming in horror.

Six small tables, three on each side of the room. Each bore the body of a child clothed in a bloodstained tunic. Spire could not determine their genders due to their unkempt hair, pallor, and emaciated bodies. Strange wires seemed to be attached to the children.

Nothing in his investigation, even that dread register, had prepared him for this: these poor, innocent souls, helpless victims of a powerful man who was viciously mad.

He raised his gaze from the children to an even greater horror, if a worse nightmare could be imagined. An auburn-haired woman in a thin chemise and petticoat was lashed to a crosslike apparatus, arms stretched out and sleeves torn away. Streams of dried blood from numerous puncture wounds stained her clothes, the cross, and the walls and floor. Below each of her lashed arms sat large bronze chalices, there was a basin at her feet. Spire knew in a glance that these were to collect the woman’s blood. What horrific sacrifice was this?

Spire turned his head to the side and retched. His mind scrambled to block out the image of who that woman reminded him of, the reason he’d become a police officer. The trauma of his childhood sprang back to haunt him at the sight of that ghastly visage in a blow to the mind, heart, and stomach. How could the world be endured if such a thing as this had come to pass? He’d asked the same question when the victim had been his mother. Nothing answered him, then or now, but sorrow.

“I never believed much in the devil,” came a soft, familiar voice near his ear, “or hell, but if I did, it would be this.” Spire spun to see a cloaked figure at his side, the solitary lantern casting a shallow beam of light upon the face of Rose Everhart.

“Miss Everhart, you should not be here. I don’t know how you got past my men,” Spire murmured, thinking it an additional horror that she should see this. “This is hardly the place—”

“For a lady? Even for the lady who handed you the critical evidence needed to arrest Tourney? Do I not wish to see him marched to the gallows as much as you do?” she replied vehemently. “Don’t I have a right to see my work completed? Don’t try my patience with references to ‘women’s delicate sensibilities.’ I’ve seen more death and tragedy than I care to relate. But, admittedly … never like this. Never like this.” She raised a handkerchief to her nose.

Spire suddenly wondered whether she had heard or seen him retch. It would be embarrassing if so.

“What are those wires?” she asked. “What are they for? Is this some sort of terrible experiment or workshop? Ritualistic, yes, but…”

Spire stepped forward, preparing however reluctantly to examine the bodies, when something lurched out of the darkness behind him with a clatter of chains and an inhuman growl. It grabbed him around the neck, grunted as it tightened its grip, and dragged him backward.

“Grange!” Rose shouted as Spire gasped for air and struggled to reach his knife. “If you’re a victim, we don’t want to hurt you,” she called in a softer tone, lifting her lantern and directing its light toward the scuffle. “Let the officer go, he’s with the police, here to help—”

Officer Grange tore down the stairs, arriving in the hellhole just as Spire managed to grasp his weapon and cut at the arm holding him. There was a wretched sound of pain from his captor and Spire felt a warm liquid trickle over his hand. Released, he staggered away and fell to his knees. Grange fired, the report of the gunshot exploding loudly in the low stone space. Spire’s assailant recoiled with a shriek. Stumbling back against the wall, it shuddered before collapsing.

Grange stood at the base of the stair with his gun raised. Rose stepped forward so the light from her lantern reached the back wall. Still gasping for air, Spire turned to view his attacker: a gaunt, muscular man with chunks of dark hair sprouting in uneven patches upon a scratched pate. The man’s skin was carved with strange markings, his eyes black and oddly reflective. Blood pumped thick and dark from the bullet wound in his shoulder, looking old and half-congealed though the injury was fresh. One arm was shackled to the wall. A guard, then, but not one to be trusted freely.

With a strange gurgling noise, a convulsion, and a wave of foul stench, the creature’s mouth sagged open and the thing expired. It then seemed as though an obscuring shadow rose from the body, then spread across the room as if it were a dark, heavy storm cloud, precipitous with dread terror.

Turning to look after the miasma as it passed, Grange, Spire, and Rose took in a startled breath at the same time. Grange cursed.

The mouths of the dead children, previously shut, were suddenly open.

As if screaming.

Silent, terrible moments passed before Spire, trying not to breathe the fetid air, stepped toward the tables, peering closer at the small, lifeless bodies. “From what I know of the telegraph and those new electric wires,” he stated, clearing his raw throat, “it seems similar. Something to convey a … transmission or charge.”

“But where do the wires lead?” Grange asked, looking at the ceiling, where the wires formed a latticework grid on the low timber-beamed ceiling. Many hung loose in gossamer metallic strands. “It seems they don’t continue on to the upper floors.”

“Go and see,” Spire commanded. Grange nodded and trotted back up the stairs.

Rose was writing upon a small pad of paper. This commonsense act—usually the first thing Spire himself did upon entering a crime scene—recalled him to himself. For an instant he was flushed with shame that this unprecedented discovery had caused him to falter in his work. He forced himself back under control; he would not allow the dead woman across the room—and what she represented—to derail him.

Though the room was cool, perspiration coated Spire and he could smell his own tension. He took out his notepad, replaced the lantern on the hook at the base of the stairs where he’d found it, and set to work. Each child’s wrists had puncture marks. Each arm bore odd carvings. He’d have to get one of the department sketch artists to accurately reproduce the markings. He wished a daguerreotype was possible, not that he wanted to subject more people to these horrors but only for the purpose of detail.

They held the man responsible, but Spire knew Tourney was not operating alone. The sheer gruesome spectacle of this would be enough, the policeman hoped, to indict any of the influential people Tourney worked with in this ghastly enterprise.

Spire turned his attention toward the woman at the back. His head swam. His mind was filled with the sounds and sights of his childhood trauma; the images superimposed over the present moment like a screen lowered before his eyes. He had to steady himself on one of the tables, hand fumbling over a small, cold foot.

A sloppily painted symbol on the woman’s tunic appeared to be a crest: red and gold with dragons. He couldn’t look at her face. He was already haunted enough by the vision of a beautiful, auburn-haired woman being bled before his eyes.

He felt more than saw the movement as Rose folded her cloak back over her head and disappeared upstairs.

Hearing voices calling his name, Spire mounted the stairs and stumbled into the light; his fellows took one look at his face and blanched.

“What’s down there?” a young patrolman asked.

“Hell,” Spire replied. “Don’t anyone move a thing until all details have been recorded. I want more than my notes to refer to. Get Phyfe down there, I want records of everything. Every single terrible detail.”

Spire sat in the fine chair Tourney had been using and continued making notes. The poor maid had been laid out on a nearby sofa; a nervous elder officer stared down at her as if afraid that if he turned his head, she’d stop breathing.

“Is there any other staff?” Spire asked.

“None that we’ve seen,” the officer replied.

He did not know how long he sat there, recording his impressions of the horrors below, before a voice startled him out of his morbid reverie.

“Harold Spire, come with me.” He snapped his head up to behold the same well-heeled footman who had been at his doorstep that morning.

“Ah, yes…” Spire rose and numbly walked to the door. “The queen’s man. Are you here to arrest me?”

“No, sir. While I had a mind to do so, Her Majesty is gracious and commends your commitment to English citizens. But you will come with me now.”

“Ah. Well. Yes. Lead on, sir.”

During the ride, Spire could think of nothing but what he had seen in that hidden cellar and what it reminded him of. He was not surprised to realize that his hands were shaking; his stomach cramped and growled, though the mere thought of food was enough to make him want to retch again.

Buckingham Palace soon loomed ahead, gradually taking up the entire view out his carriage window. The hansom drew up to a rear door and Harold Spire found himself led by the stern footman through a concealed entrance, along a gilded hall, and into a tiny white room that contained only a single item: one fine chair.

The space had no windows, only a door with a panel at eye level. The footman closed the door firmly, leaving Spire alone in the cupboard of a room. “Would someone mind giving me even a partial clue as to what’s going on?” Spire called, glad he had restrained from cursing when answer came, as the voice was a familiar one.

“Hello, Mr. Spire,” was the reply from the other side of the wall.

Lord Black.

Spire wanted to spill all the information about the case, as Black had been critical to its culmination, but would hardly do so across a wall.

“Give me a moment, Mr. Spire, if you please.” Spire then heard two voices beyond the threshold, talking about him. Neither man bothered to lower his voice; obviously they did not care if they were overheard.

# # #

“Humble thanks, my dear Lord Denbury,” Lord Black said, bowing his blond head to the handsome young man with eerie blue eyes seated next to him in the lavish palace receiving room. The immaculately dressed gentlemen each held a snifter of the finest brandy. “Firstly, for the use of your Greenwich estate. Her Majesty is most grateful to have a place where her scientists and doctors may be safe and undisturbed as they study the mysteries of life and death.”

“Provided your aim is always the health of humankind rather than personal gain, you shall have my support, milord,” the young man said, bowing his black-haired head in return. “That house has … too many memories,” he added. “I love my New York mansion far more.”

“Ah, yes!” Lord Black leaned forward with great interest. “New York…”

“My wife is a consummate New Yorker, born and raised,” Denbury said with a smile. “I see the city as I see her: bold, opinionated, and beautiful. I love it. You should visit.”

Black nodded. “I plan to. Secondly, I must thank you for coming here on vague bidding.”

“I hate secrets,” the young man said in a cautious tone. “After all I’ve been through.”

“Of course.” Lord Black spoke with quiet gravity. “So let me be direct with you now. I need a chief of security services for those scientists and doctors and I’d like your … expertise in determining character. I understand you … see it like none other.”

Lord Denbury sighed wearily but nodded. Both men rose; Lord Black opened the eye-level panel in the door and bade the other look through.

“His name is Harold Spire,” Black said. “What do you make of him?”

The man in question, seated on the velvet chair in the white room, wore a modest black suit. Scowling, he rested his hands in his lap. His green cravat gave the impression of having been hastily tied; it was rumpled and a bit askew. There were smudges upon his suit as if he’d encountered dust or soot and there was a dark stain on his cuff. At a median British height with light brown hair, Spire’s average appearance might be gamesome, possibly even handsome, if the scowl didn’t make him somewhat of a bulldog.

“What do you see?” Black murmured to his companion.

“Well,” Lord Denbury began matter-of-factly. “He’s had a terrible day by the look of him. He bears a general white aura with hints of blue, which represents that he means well and is at heart a good man, untroubled and unbiased by exterior forces. He will do the right and moral thing. Provided that is what you want, Lord Black, you and he should not be at cross purposes.”

Lord Black smiled as he shut the observation panel. “I assure you, my friend, that I want what is moral, just, and fair.”

“I see the same light about you,” the dark-haired man replied. “But should those colors change, you’ll no longer have my friendship. I’m sorry if that seems harsh, but the trials of the last two years have inured me to niceties.

“Is that all, milord? I’ve left my dear wife anxiously awaiting her surprise: a trip to Paris. She’s impossible when she’s impatient … and she’s never patient,” he added with a smile that spoke of the throes of young love.

Black chuckled. “Indeed, you are released and I cannot thank you enough. Safe travels to you and yours.”

Denbury bowed his head and strode away, escorted by an immaculately clad footman.

Black turned to his aide. “Tell Her Majesty that Mr. Spire passed the test.”

Lord Black hadn’t told Lord Denbury that the scientists and doctors stationed at Rosecrest, the Denbury estate, had recently gone missing, along with the security chief assigned to them. If the cable he’d received from a contact in America was to be believed, the Americans weren’t having a good time of it either. He had to wonder if the incidents were related, somehow. Impossible as that seemed.

He turned as a rustle of skirts heralded the formidable presence coming his way.

“Ah, Your Majesty.” Lord Black bowed low to the diminutive sovereign. Her stern face with its round cheeks was framed in white lace while the rest of her was engulfed in black taffeta, dripping beads of Whitby jet. “Spire has been cleared.”

# # #

Spire waited, not entirely patiently, for several minutes before Lord Black opened the door and gestured for him to leave the tiny, plain room. Eager to bring the handsome, slender, fine-featured blonde up to date, Spire began, “Tourney, Lord Black—it’s done. But what I found—”

Black held up a hand. His tense smile flexed the scar that ran from above his right eyebrow down into his cheek. Spire often wondered about the origin of that scar, but never asked. “Good work, Spire. The queen awaits you. But first…”

The sour-faced footman stepped up with a black suit coat in hand. “You look as though you’ve traversed every layer of Dante’s inferno,” the man said.

“Oh, just come right out and say I look like hell,” Spire muttered, staring at Lord Black. “I saw hell. It’s worse than anything you could have imagined.”

The footman grabbed his sooty coat and slid it off his arms, then muscled on the fresh jacket though it in no way fit. Spire feared he’d split the seams with the least shift of his shoulders, which were far too broad for the fine fabric. The too-short sleeves didn’t entirely hide the patch of blood on his shirt cuff. Shuddering at the memory of where he’d acquired the stain, Spire tried to tuck it out of sight. Black nodded Spire toward the receiving room.

He was shown in wordlessly; the door closed quietly behind him.

The surreality of Harold Spire’s day was heightened by the lavish setting of Buckingham Palace, worlds away from his life and laughable when compared to the horror of his morning duties. He’d passed around the outside of the building during parades and once had visited the main foyer, but never before had he gained entrance to one of the receiving rooms. It was full of things; lacquered things, mirrored and crystalline things, tasseled and brocaded things. Strains of music wafted into the tall, bright room, perhaps from a ballroom: a string quartet playing Bach. Spire preferred dark-paneled rooms filled with books. And good whiskey. And Chopin. And a coat that fit.

“Your Highness,” Spire said, paying due deference to Her Majesty Queen Victoria, who stood facing away from him, hand upon the crest of a large armchair, turned toward a tall window with lace curtains partly drawn. Spire stepped forward, noticing that the marble-topped writing desk beside the queen was covered with maps of New York City and schematics for an ocean liner. A telegraph machine sat silent on the desktop, gleaming in the sunlight.

“Mr. Spire,” she began without turning to look at him, speaking in a grand way that left no room for interruption, “I have called you here to give you an appointment. You rose quickly through the ranks of the Metropolitan Police. I’ve been assured you are fair and just, keen to recognize patterns and aberrations that catch criminals, swift and smooth with your decisions. But perhaps too quick to spy.”

Spire felt heat rise in his face; he glanced into the golden-framed mirror on the wall next to him and saw his fair skin had colored all the way up to the roots of his light brown hair.

“I was afraid that’s what this was about. Please, your Highness, I’ve personally apologized to the prime minister and to Miss Everhart. A cloaked female utilizing secret passages within a subsection of Parliament does seem suspicious, surely—” He hoped he didn’t sound whiny.

“As you know, that was to hide the fact that the P.M. had employed a lady as his chief bookkeeper. Imagine the outcry. But this isn’t about the prime minister or his employees. You come highly recommended by Lord Black.” She turned around at last. Her eyes were shrouded by dark lenses connected by a curving filigree bridge. He must have looked quizzical, because she paused and said, “Lenses cut from a scrying glass, in hopes I’ll see the dead.”

When Spire simply nodded, the queen cocked her head. “Not him, necessarily,” she scoffed. “I know what you’re thinking.”

That the queen still dressed in mourning for her husband, Prince Albert, many years deceased, and entertained all sorts of ideas of how to contact him—not to mention sleeping beside a picture of him and placing out his fresh clothes each day—had become a quiet joke in the realm.

“What am I thinking, Your Majesty?” Spire asked innocently.

“Oh, come now”—she batted her hand in irritation—“it’s as if you all think I go about dragging his coffin behind me everywhere I go.”

“I thought I saw parallel scratches on the wooden floor,” Spire said, gesturing down the hall. “That explains it.” He smiled.

The queen tried to scowl but instead coughed a laugh. She removed her glasses, piercing him with a stare. The short, plump-cheeked woman was downright disconcerting when she deployed her steely gaze. She was Empress, after all.

“What is wrong with you, Mr. Spire? You look dreadful and you need a better tailor.”

“I came direct from a crime scene, Your Majesty, my apologies. I thought your gentleman explained—”

“Ah, yes, yes, Tourney and the resurrectionist ring. Tell me, how large of an operation do you deem it?”

“Between the financial speculation and the body snatching, I imagine it may be a wide net. The ledger we found will condemn the ring, though there was a…” He trailed off, unsure how much of the dreadful scene to speak of. The Queen simply stared at him expectantly. At last he swallowed back a wave of sour saliva and continued, “A peculiar crest was discovered.… Well, it all had a ring of … ritual to it, Your Majesty.”

The queen snapped her head to the side and it was only then that Spire noticed Black had slipped into the room behind him. “Ascertain that crest,” she snarled. “If it remains from Moriel’s tenure, I want them all to hang.” Lord Black nodded reassuringly. Spire was pleased the queen was taking the matter as seriously as she should.

“Mr. Spire,” the queen said, “I am about to tell you a state secret known only to a few. The Eterna Compound was first sought in America after the assassination of President Lincoln. A bold idea, born of grief. I well understand Mrs. Lincoln’s woes. A small team of theorists made no progress in their research until two years ago. But now there is a fresh impasse. As I have full faith in my realm, I believe we can fix the Americans’ mistakes and make the compound viable.”

“May I ask what the Eterna Compound is, Your Majesty?”

“A cure for death. A drug that confers immortality. I’ve had a team compiling information and studying the idea for years.”

Spire kept his face unreadable, his skepticism hidden. “And do we? Have the cure for death?”

The queen shook her head. “Our plant within the operation has not reported as scheduled. We hope to retrieve information and material from New York; material that you, Mr. Spire, will safeguard. Other Special Branches of investigation and prosecution will counter various political threats. Your division, Omega, will counter the greatest threat of all: a nation that could make its leader immortal. We cannot allow America to gain the upper hand in immortality. I empathize with Mrs. Lincoln but have no desire to confront an utterly impervious American president.”

Lord Black stepped forward and spoke carefully. “The British operation is … paused. Our facility was recently compromised. You will safeguard fresh intelligence and a new team, in offices that are presently being prepared. You must focus on life and death in a whole new way, Mr. Spire. All other matters of mundane police work must be cast off to the fellows you leave behind at the Metropolitan Police.”

Spire reeled. This appointment was a nightmare. The queen had the wrong man. Spire didn’t believe a word of any of this. A cure for death? How could he manage an operation he couldn’t take seriously? He broached the only comfort he could cling to, the resolution of the horror he’d faced.

“But today’s findings were hardly mundane; the work not of mere Burkes and Hares but something even more insidious.…” Panic threatened to overtake him as the images rose in his mind.

Lord Black stepped close and flashed Spire a look of warning as he poured whiskey from a crystal decanter into a pair of matching snifters. “Material and information will arrive from New York,” Black said smoothly as he handed Spire a glass, “and your focus must be upon it, Mr. Spire. I will personally see to it that the Metropolitan follows every Tourney lead.” From the flash of fury in the man’s eyes, Spire knew Black meant what he said and recalled it was Black himself who had obtained the ledger Miss Everhart had given him. More than he’d ever have expected of an aristocrat in the House of Lords.

Spire fought the urge to drain the snifter as the queen delicately lifted a cup and saucer of tea. Then she stung him.

“That you have suffered grave loss and then been betrayed by love, and in such a way as to cost state secrets may be something a man might be ashamed of,” the queen began, “but I look upon it as a gift. Your cautious care, a healthy ability to second-guess, a lack of trust, this will all be very valuable. Trust no one. Not at first.”

Spire swallowed hard. The queen had most certainly read up on him. His mother’s death had been a bit of a media circus at the time, and his father had done nothing to calm the frothing “journalists.” Then, Alice. He’d been too naive to have imagined that an officer like him, assigned at that time around the Houses of Parliament and surrounding neighborhoods, would have been of interest to French agents. He’d never dreamed they’d employ a lady—and Alice Helms, now Madame Lourie, had easily taken advantage of him. He had been a fool and women were a source of woe.

“And so I look at the whole of your history and see the sort of solid man I can depend on, one who has been scarred in all the right places. One must build up scars in war. And we are engaged in a most unusual war here, Mr. Spire. I need you scarred. Sane. And unafraid.”

Spire nodded.

“As we speak, all your belongings are being transferred to rooms in Westminster; Rochester Street, lovely accommodations unregistered and unlisted, a vast improvement from your current subsistence,” the queen continued casually. “Bertram will give you the keys. You will share your address only with the most trusted members of your assigned team, and only once you have ascertained their loyalty.”

“Yes, Your Majesty.” Spire bristled but managed to keep his tone level. He was a private man. That persons had been in his home and uprooted his possessions made him clench his fists.

“Lord Black will see to your new offices. Tell your Metropolitan fellows nothing save that you’ve been transferred. You’ll liaise further with a contact at the British Museum.”

“With all due respect, Your Majesty,” Spire offered quietly, “I cannot in good faith abandon the Tourney case.”

“I insist that you do,” she replied stridently.

Spire swallowed hard. He would not disobey the queen. Not to her face. Instead he changed the subject.

“Your Majesty, I’m sorry, I have to ask, considering the bent of this commission … Did my father put you up to this?”

The queen arched a brow. She was not amused. “Victor Spire?” She scoffed. “Author of penny dreadfuls, Gothic novels, and sensationalist plays? Have audience with Her Majesty the Queen?”

“Ah, no, of course not. Forgive me for bringing him up,” Spire said, mustering sincerity, biting back the urge to say that he knew firsthand she had secretly attended his father’s latest show; after all, his men had seen to her protection. “But a race for immortality. It sounds like something he’d serialize in Dickens’ magazine.”

The regent stiffened. “Dare you imply, Mr. Spire, that this position is not to be taken seriously?”

“Of course not, Your Majesty, pardon me,” Spire said, bowing his head. “Unlike my father, I have retained appreciation only for the concrete, tactile, apprehendable, and solvable.”

“Apply those very principles going forward, Mr. Spire.” The queen clapped her hands once. Her serious, jowled face grew even more intense. “Tell your father his last novel was dreadful.”

“You read it, Your Majesty?”

“Every word,” she said with exaggerated disdain. “Truly dreadful stuff.”

“Agreed, Your Majesty.”

“Good-bye, Mr. Spire. Good luck and do good work.”

Spire bowed his head as the regent swept away amid the clicking of beads and the swishing of silk. The sour-faced footman showed him out a different door, first retrieving the excellent, though too small, coat and, with a curled lip, handing over Spire’s soot-stained jacket as well as a brass key with a number on the fob.

Stuffing the key to a whole new existence into the pocket of his long, black, velvet-trimmed, fitted coat, Spire couldn’t deny he was curious. He could go examine the place, test the walls, see if they’d granted him hidden compartments and revolving bookcases. Hopefully there was a wine cellar.

To leaven his darkening mood Spire lost himself as he loved to do: in the smoky, sooty, horse-befouled, hustling chaos of London proper, reveling in the onslaught of sensory input that drowned out all concerns, doubts, and anxiety. The crashing, audible waves of London always trumped the drumming of the mind; the roaring aorta churning the very heart of the world won out every time over one’s own racing pulse. He let the chaos of London in like a man might smoke an opium pipe, allowing the high to carry him about the city on a cloud of stimuli.

Spire trailed a nervous man in a brown greatcoat for two miles simply for the sake of proving he could do so unnoticed. He chose his subject after overhearing him lie to a pretty girl leaning out the window of a brougham—narrowing in on one conversation out of the melee, it was as though Spire could hear a single, subtle line of dissonance in a rollicking symphony. The young man sent the blushing, giggling girl off, saying he was going west. Instead he took off east, stuffing his hands in his pockets, a sheen of moisture over his lip.

It wasn’t that Spire assumed everyone was guilty of something, but years of honing perceptions, translating body language, reading movement and expression, ascertaining habits, casting judgments, all made him suspicious of nearly everyone at first glance. Trust no one, the queen had said. Spire had abided by that edict for years, ever since Alice … Since her, he hardly trusted himself.

Now he was being entrusted with state secrets coming from the highest channels. Ridiculous ones at that. Should he have said outright that he didn’t believe in the supernatural? Skepticism had its uses. If the queen needed him to be a believer, she should have asked him.

That the man in the brown coat went into a jewelry shop and came out with an engagement ring—Spire had leaned against the shop window on Farringdon Road to eavesdrop upon the conversation with the clerk—filled him with a certain joy. He loved to be proven wrong. It didn’t happen often enough. And if he didn’t treasure those instances when the brighter side of humanity showed its face, he’d have to throw himself in the Thames.

He doubted the sights of that basement would ever leave his thoughts, and offered something of a prayer upward, toward an entity he regarded with as much skepticism as he did anything outside his own mind and body, hoping something about his new appointment might make for the ability to seek out further answers. For what could drive creatures to do such horrific things if they were not possessed, maddened, by the intrigue of life and death?

Regardless of motive or madness, to the point of risking treason, he’d hardly abandon the case.

CHAPTER TWO

New York City, 1882

The tumult of New York harbor was deafening. There was confusion, concern, even panic on the docks at the tip of Manhattan Island. Ahead of Clara, as she looked out past schooners and ferry boats, lay the first tier of the pedestal that would eventually host Bartholdi’s Lady Liberty … if New York could ever pay for her. Clara thought with a profound sadness that perhaps Liberty would never lift her lamp high over the water, not if all those warships meant anything.

A fleet of Britain’s warships, the Union Jack flying high and proud upon every mast: the world’s greatest navy, amassing at the tip of America’s greatest city. A dread chill coursed through Clara’s veins and she clutched her shawl tighter around her neck.

England would make America theirs after all. A colony it simply could not let go.

The act of a monarchy that could never die.

Never die.

“Wake up!”

Clara’s eyes shot open as she bolted upright. The ruffles of her nightdress, which she’d bunched up around her neck during her nightmare, fell back down in a splay of fine layered lace.

Given the words that had roused her, Clara Templeton expected the visitor to be sitting at the foot of the wide bed she had once hoped to share with Louis Dupris. But the visionary young chemist and theorist had died yesterday, and the voice was not the visitor’s but a renewed urging from beyond. More was being asked of her than mere living.

She had returned from the park to the Pearl Street town house she shared with her guardian, Senator Rupert Bishop. Having written a note stating her instinctual certainty that something terrible had happened to the team, Clara slid the sheet of paper under the door of Bishop’s study and locked herself in her room. She’d have ignored his orders that she never visit the laboratory site if she’d thought anything could’ve been done. But the visitor had confirmed her instincts. Whatever the disaster—a fire, an explosion, an unexpected reaction of any kind—she prayed they had not suffered.

The senator kept late hours and traveled often, his schedule changing on a dime, so despite her best efforts to know his calendar, Clara wasn’t sure when he’d see her note. But as the secrecy of the commission couldn’t be broached by sending policemen to the laboratory, she needed him to decide on their next steps.

Sunlight streamed in through the exquisite craftsmanship of the Tiffany glass window of Clara’s bedroom, through glowing, textured milky magnolia petals that cast pale yellowish spots upon her white satin bedclothes. Turning to one side, Clara stared into the mirror of her rosewood vanity, meeting her own terrified gaze. Waves of dark-blond hair framed her oval face in a wild mane. With wide eyes that were more eerily golden than they were green, and her mouth open, she looked like a mad Pre-Raphaelite painting, Ophelia just before the drowning.

In her hand, a saffron-colored strip of fabric.

A fine silk cravat.

Louis Dupris had left it behind after one of their harried tumbles of lips and hands and she’d been too fond of him to return it, instead secreting it away in a compartment of her jewelry box. The amulet he had bequeathed to her and this cravat was all she had of him; she’d fallen restlessly asleep clutching it.

She rose and went to her wardrobe to begin the feminine ritual of donning innumerable layers. She opened her bedroom door for a moment to listen for sounds from elsewhere in the house, but all was silent. That was for the best, lest she spill everything to the senator in one look.

Rupert Bishop gave her everything she needed; he was her mentor and her joy. He’d taught her everything she knew and remained her spiritual counselor. Her relationship with him was complicated and nearly impossible to describe. Once he might have been her Great Love. Epic, sweeping, and all-consuming. But was that this life? She doubted so. Once she’d asked him if he felt whole.

“Frankly, I don’t know,” he’d mused. “This life is full of fragments. We’re all torn apart.”

It was not an answer, but it told her enough: she was not what he was missing. She buried her feelings. “Do you feel whole, then?” he asked her in turn.

She shook her head. But until she understood the exact shape of the puzzle-piece holes within, she did not dare pinpoint exactly what might fill them. With Rupert she had to take immaculate care. When all her school and society friends abandoned her at age thirteen, when her seizures started—none wanted to be seen or associated with such an unfortunate—Rupert was all she had. She dared not do a single thing to jeopardize that. Even calling him Rupert often felt too familiar, an intimacy she relished but one that frightened her. And so, as everyone else called him either Bishop or Senator, so did Clara, pressing love for him so deep into the recesses of her heart that it had fossilized.

Who did the visitor mean by her “missing link?”

Clara had toyed once with channeling some of her overwhelming sentiment into something productive. A novel. A memoir. She still felt with that ardor that, at twelve years of age, had had her blurting impossible things to powerful people. But when she tried to put her thoughts into words, the result was unwieldy and read like the scribblings of a naive schoolgirl. No reader would believe the intensity of her feelings; none would understand that she was a soul with every nerve ending accessible. Perhaps in childhood, all souls were similarly exposed. But grown persons were calloused; keeping a fragile heart was physically and psychically dangerous. The bounds of human flesh were finite. After all, when dead, the heart was mere flesh. Clara’s material world was small, but her spirit was as vast as the sky.

So Clara did not write. Instead, she went to work. Good, honest, busy work; the salve to both emotional deficits and oversensitivities.

In the Pearl Street offices she balanced the books on the Eterna teams’ expenses, ensuring fresh supplies of basic chemicals and minerals, the most modern medical manuals and textbooks of interest, with a budget left over for items of “spiritual” interest.

When it came to matters “paranormal,” she was more directly involved. She interviewed those who reported strange phenomena, then filed the results at the office. She and Senator Bishop kept an eye on theatrical psychics and other spiritualist charlatans, warning them when they went too far in taking advantage of the grieving or bored.

Clara occasionally accompanied the senator on campaigns. She volunteered for New York City’s ASPCA, a cause the Templeton clan had long championed as friends of the organization’s inimitable founder, Henry Bergh. She visited her parents’ mausoleum in gorgeous Greenwood weekly, taking the trolley to the Gothic gates and passing the day in lavishly carved stone shade. What company could be more beautiful than those stone angels? She kept herself occupied. She needed no lovers or close friends.

Until Louis Dupris came along as the capstone to the Eterna research team and upended her entire, prematurely spinsterish, calcified universe.

They had met at a soiree at the infamous Vanderbilt mansion. The details were emblazoned in her memory. She had stepped into a shadowy alcove, deliberately out of Bishop’s line of sight, when suddenly an exceedingly handsome, olive-skinned man in a fitted black suit blocked her path.

Clara took a moment to psychically evaluate him and determined she was in no physical danger. His piercing hazel eyes bored into her with thrilling intensity. “You’re in my way, sir,” she said quietly.

“So I am. I’ve been instructed not to introduce myself,” the man began, in a rich, deep voice. “And while I do value my new job as my life, that life would be forfeit if I did not at least tell you that you are, by far, the most interesting creature in this entire room, if not this entire city. Save, perhaps, your guardian, my employer, who insisted you were quite off-limits. This would make any woman all the more fascinating were you not so utterly time-stopping on your own. I understand now why the senator is so protective of you.”

Clara laughed. “Did my dear Bishop employ you merely for flattery?”

“No, my lady, he employed me for theory and faith. How I might apply spiritual concepts and principles into the quest of immortality as pursued by your department.”

“Ah, you’re one of ours!” she commented brightly. “You’re new. Where do you hail from? Your accent is distinct.”

“New Orleans, my lady, a distinct city indeed.” He bowed. “Louis Dupris, at your service, Miss Templeton. I hope my overtures do not offend. It may be that I never speak with you again, as I value my work and the senator deeply. But there are times when a man must speak or forever regret the chance, and you evoke that prescient timeliness.”

She cocked her head to the side gamesomely, the plumes of her fascinator rustling. “You should come to call, Mr. Dupris.”

“I couldn’t … I can’t.”

“But you should,” she insisted sweetly. He looked uncomfortable. She chuckled. “In secret, then, if you’re so worried about the senator’s wrath.” She batted her silk-gloved hand. “Come stroll with me on Tuesday, through the Greek and Roman relics at our glorious Metropolitan Museum. At two. Tell me about spiritual disciplines I know little of.”

And then she’d had a seizure. Right in middle of the Vanderbilts’ home.

Whenever too many ghostly voices or psychic phenomena pressed in upon her at once, Clara had an “episode.” Generally her body gave her an aura of warning and she would exit a place before any damage was done. Distracted by the party, by Louis, by all the glamour and finery, she’d missed the telltale signs. She hadn’t had a “fit” in years and was more mortified than ever by the condition she’d been fighting since the age of thirteen. While she knew she had nothing to be ashamed of, the world wasn’t so generous. Especially not at a Vanderbilt party.

Bishop had taken her home immediately and Clara had assumed she had seen the last of Louis Dupris. That she had gone to the museum on Tuesday spoke of her essentially optimistic nature—and her fondness for the museum’s marble halls.

To her great surprise, Mr. Dupris was entirely undeterred by her ignominious departure from the Vanderbilts’. He met her at the museum at the appointed time, and at every place and time they could find after that. Happily, the great city abounded with secluded spaces. Cemeteries became their collective haunt as they mused on life and death. Clara sensed that her soul and Louis’s had gone round together at least once in the past. He hadn’t betrayed or brutalized her then, so why not indulge the blossoming bond in this life?

Louis found her seizures, the aura she saw, the way her senses abandoned her and returned in pieces, entirely fascinating. His acceptance won her trust. He taught her how to block out the spiritual press, lessons born from his own studies of spiritual and theological matters. She had, after his tutelage, been fit-free for two years.

He was her visionary, insatiably curious and confidently ambitious. No matter what other matters called to his attention, he remained enthralled with Clara, and she with him. Now he was dead and she had no way to quantify the grief she felt, no way to show it, for she and Louis Dupris had never even met, as far as the outside world was concerned.

She would have to, she realized, live her current life denied of many things. Her heart hardened. It had to. While she knew, as a spiritualist, that the spirit lived on, death had made her cold. She thought of Greenwood’s stone angels and wanted to become one of them.

The Eterna team was dead. Did anyone know, other than Clara?

She tucked the saffron cravat into her corset, against her bosom, and set off to be the center of the presaged storm.

# # #

“It was as I feared,” said Louis Dupris as he trailed his brother Andre through downtown Manhattan at the crack of dawn, floating a foot off the ground.

Andre tore down Broadway, surely appearing mad talking to thin air; thin, cold air in the shape of his twin.… He shuddered. He could not begin to process the horror he’d seen.

“Don’t tell me you predicted that hell that took you?” Andre growled at the ghost, a gray-shaded, near-transparent image of his brother. “Your whole team? I can’t begin to understand—”

“Something was in that house. We were not alone. But what it was, or why our compounds made it come alive, I can’t understand. Perhaps, in death,” Louis continued excitedly, “I can learn more! Perhaps here I can do more good, in this state—”

“I’d rather you were alive,” Andre said mordantly. “That we’d traded places.”

“Don’t say that, brother,” Louis exclaimed earnestly.

Perhaps Louis would have agreed to the switch if he knew the whole truth; that for many months, Andre had been spying on Eterna on behalf of England.

“Perhaps your partner Malachi’s rabid paranoia was founded,” Andre muttered. “You’re right, you were not alone there. You were certainly being watched, and not only by me.”

In a fit of overwhelming paranoia, one of the researchers had ordered the Eterna theorists to move their laboratory into his eerily empty town house. They humored him to keep a fragile peace. Louis had Andre store his most precious notes and research in another location, trust swiftly eroding between the once-filial team. Disaster struck the very next day.

Andre would never be able to purge the memories of the Eterna researchers falling to the floor, suffocated by strange, creeping tendrils of smoke, by a presence that Andre didn’t wait around to experience for himself. No, Andre did what he’d always done as the black sheep no one spoke about—he ran. But lest he go to his own grave an utter coward, he would do his best to help his brother find peace.

“Today we begin to set things right,” Andre declared, brandishing a small envelope. He moved at a harried clip that was not unusual for New York, though his anxiety trumped the speed of the average pedestrian out at such an early hour. “I’ll turn this over, then return that damned dagger you stole to New Orleans, praying to all your mystères for protection along the way.”

“Don’t mock the mystères, brother,” Louis scolded.

“I’ll believe in them if they protect me against one very angry woman,” Andre retorted. “Of all the people you crossed coming to New York, it had to be a Laveau protégée? Bon dieu! I suppose it’s only fitting penance I be the one to see this through.”

“You’re not the irredeemable sinner you think, Andre—”

“But I am!” Andre insisted in a coarse whisper. “I lied to you, Louis! I wasn’t interested in Eterna because of you, but for my own interests. You gave me secret refuge and I squandered it. Trust me, I’ve a lot to answer for. Slates must be cleaned. Yours and mine. But someone should know what happened to you, Louis,” Andre stated. “Your sweetheart, perhaps? You adored her, that woman deserves answers—”

“Keep Clara out of it,” Louis warned, an icy whisper in Andre’s ear, “with her condition, I shouldn’t—”

“I’ll leave the key. If they’re as clever as you say, they can figure out what it belongs to without incriminating me. And then I’ll be on my way home, none the wiser for my presence.”

Louis’s anxiety was unassuaged. “You hid my papers as I asked, didn’t you?”

“I left what you gave me at the college,” Andre assured. Whether or not he’d be telling his employers about the materials or the disaster, he had yet to decide. He wanted to wash his hands of all of it, be done with spying. But survival first. Strategy second.

Andre stared up at the Romanesque edifice, dark and looming in the early light. Louis’s presence was a cold draft at his neck. The living man shifted the envelope from one hand to the other, considering his task. The door was locked. Andre flipped back the thick cuff of his sleeve to reveal several thin metal implements. In mere moments the lock had been picked and the door swung wide.

“Do I want to know where you learned that?” spectral Louis murmured.

“The bad egg survives,” Andre muttered.

Charging up to the third floor, Andre threw wide a wooden door to reveal a long dark room whose decor looked more a lady’s parlor than an office. Depositing the envelope conspicuously in an empty tray, he sped out again. “Onward toward resolution,” he rallied. “And vanishing from the record.”

He darted out onto Pearl Street, tipped a wide-brimmed hat lower over his brow and turned back to see Louis floating in front of the building, his grayscale form immeasurably eerie in the misty, waterfront dawn. After a moment, he wafted to Andre’s side.

“There’s so much Clara and I should have shared,” Louis murmured.

Andre shifted on his feet. “You never told her about me, did you?”

“No,” Louis insisted. “You came to me in trouble. I never told her I had a twin or betrayed your confidence.”

“And I never deserved a brother so good, loyal, and true,” Andre said bitterly, for the first time feeling tears well up. He wouldn’t tell England another word, he decided.

In the tumultuous, heaving throng, the sheer, maddening bustle that was New York Harbor, Andre made his way through a deep maze of wood and steel, planks, ropes, and sail. One small leather pack slung over his back, a precious ceremonial dagger well-hidden on his person, he wove swiftly to the docks. Louis floating beside him, traveling right through anyone in his way … persons who would think him nothing but a breath of cool breeze.

Despite Andre’s speed and twisting path, he noticed that a particular face was never far from him in the throng. Even crowded onto the ship that should have carried him safely away, his desire to vanish was thwarted. The follower spoke to the captain in a soft, upper-class British accent. And stared right at Andre where he stood among the massed humanity on deck.

“Damn you, Lord Black, and your spies,” Andre muttered. “Damn you all to hell.”

# # #

Franklin Fordham lived alone in the stately, Federal-style Brooklyn Heights house the rest of his family had abandoned after his brother’s death in the war, his mother having found it impossible not to be haunted by the place. Franklin bore his own suffering like a pebble in his shoe that he never removed. His brother was dead and Franklin hadn’t been there, fighting at his side, due to a bad leg. Living in the home they had once shared was a form of penance.

At a sharp rap, he opened the town house door to a most lovely, welcome sight.

There, framed by dappled sunlight filtering through the growing trees behind her, beneath a rose lace parasol, was the woman who had once cut through darkness and saved Franklin’s mind, like an angel descending through storm clouds.

Clara Templeton was dressed beguilingly as ever, today all in burgundy; a black-buttoned jacket with fitted sleeves over gathered, doubled skirts, a small black riding hat with a burgundy ribbon set at a jaunty angle on her head. Despite her broad shoulders, she was slight in girth, yet Franklin knew she was capable of great strength. As he looked at a face more suited to a classic painting of an infamous woman from history than to this era’s praised softness, he noted that she seemed unusually drawn. The oft-mischievous slant of her pursed lips seemed strained and her luminous green-gold eyes were hidden behind small, tinted glasses.

Not for the first time, Franklin thought that Clara was a magical creature. It wasn’t that she was beautiful, though an argument could be made for her unusual beauty, it was that she was lit from within by an indomitable fire, both terrifying and wonderful.

“Miss Templeton,” he greeted her with a smile. “To what do I owe this pleasure on a day off?”

“They’re dead, Franklin,” she said quietly, each word like the faraway toll of a bell. “The whole team is dead.”

Franklin stared at her. “What? How? How do you know?”

“I simply know that they are gone,” she continued in a deadened tone. “And this morning I had a dream that in the near future the English would invade.”

“Well then,” Franklin said, turning to the wardrobe by the door to withdraw a lightweight brown frock coat, hat, gloves, and an eagle-topped walking stick. Clara’s dreams and instincts were serious business he’d learned not to trifle with.