opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

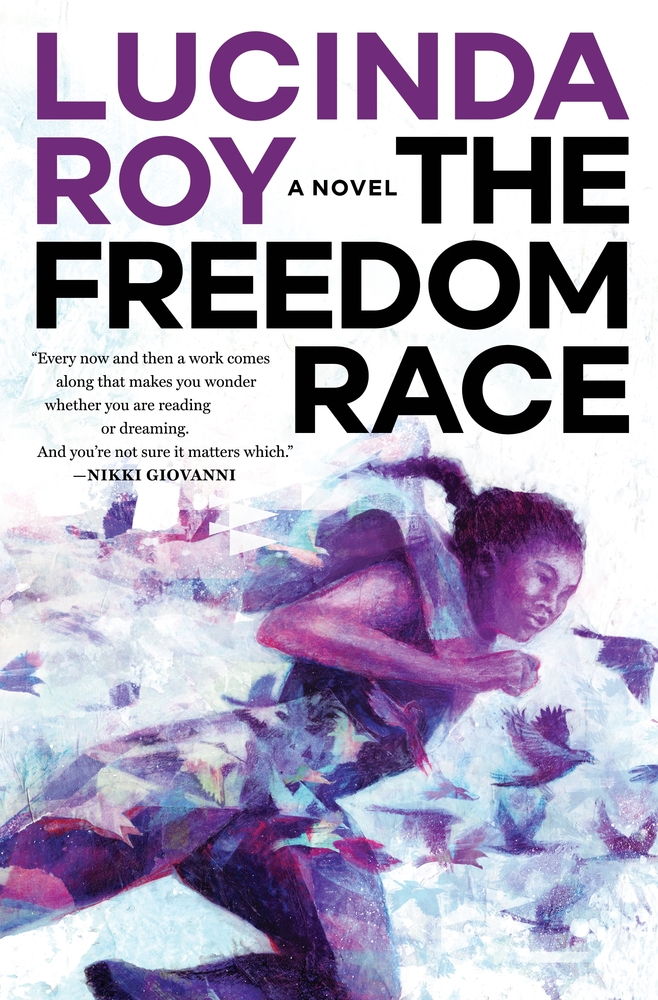

The Freedom Race, Lucinda Roy’s explosive first foray into speculative fiction, is a poignant blend of subjugation, resistance, and hope.

The Freedom Race, Lucinda Roy’s explosive first foray into speculative fiction, is a poignant blend of subjugation, resistance, and hope.

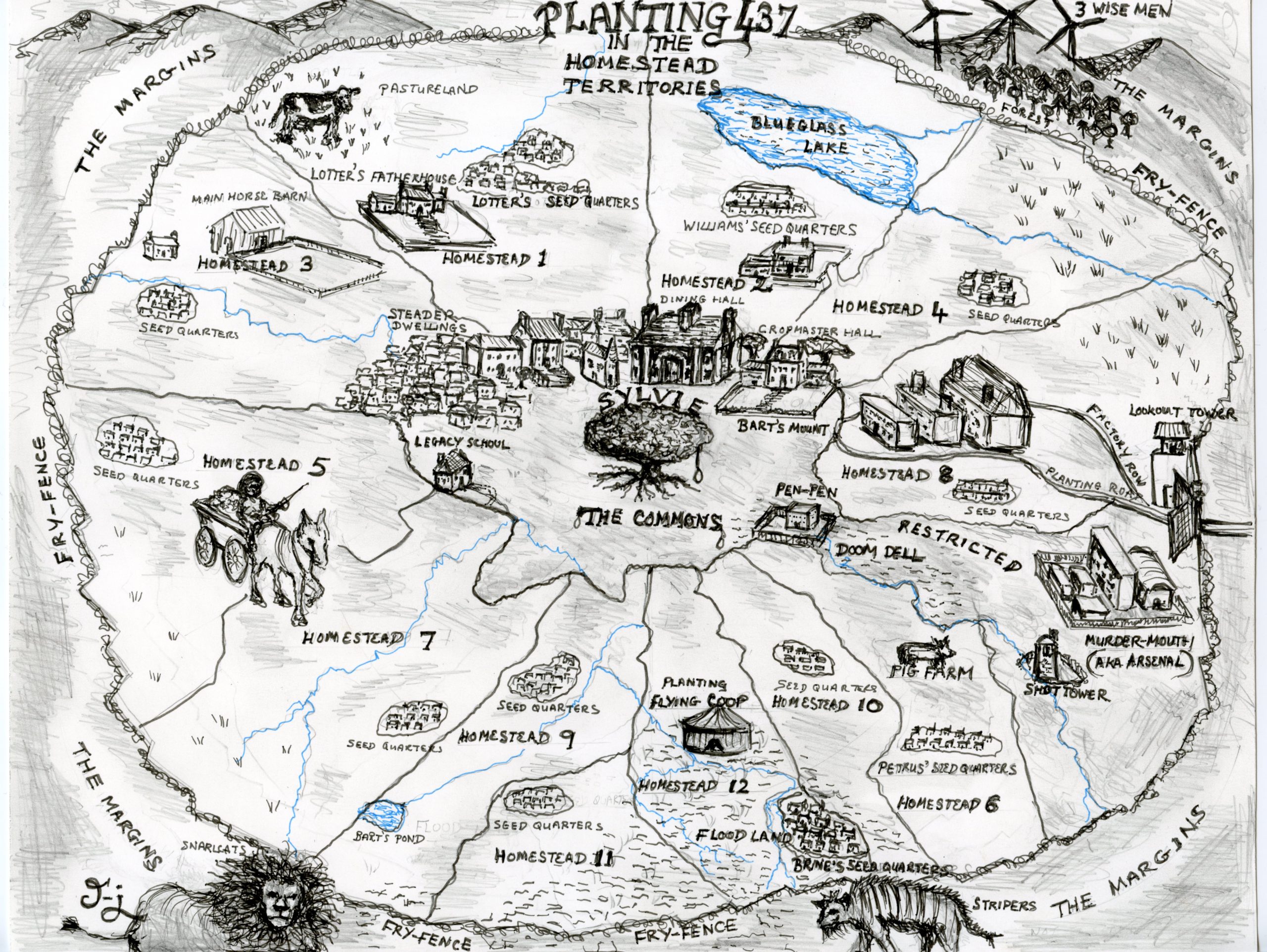

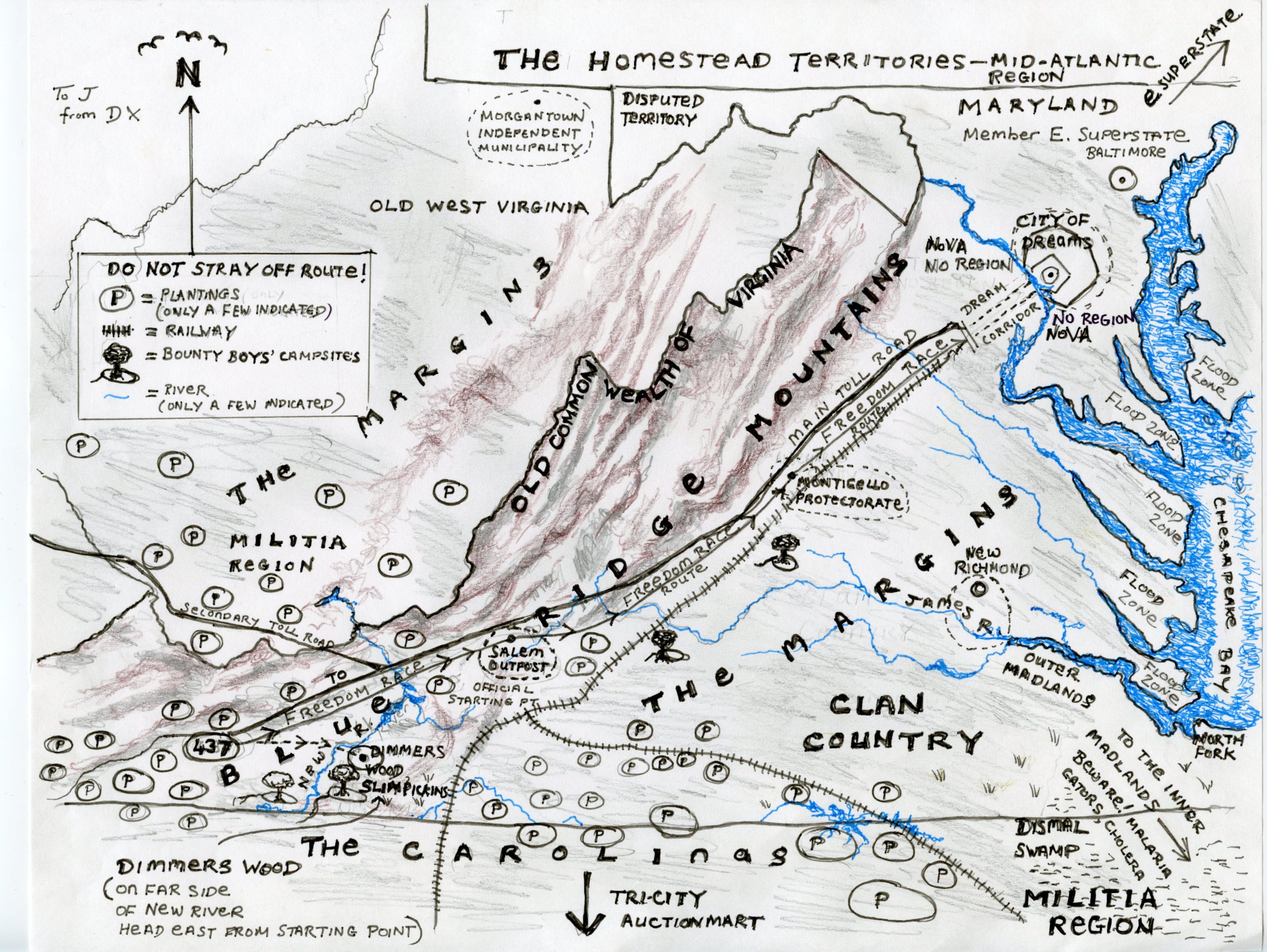

In the aftermath of a cataclysmic civil war known as the Sequel, ideological divisions among the states have hardened. In the Homestead Territories, an alliance of plantation-inspired holdings, Black labor is imported from the Cradle, and Biracial “Muleseeds” are bred.

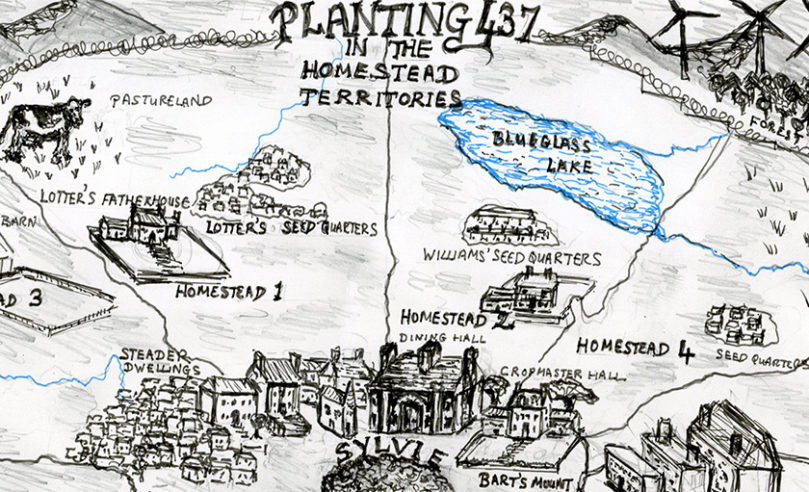

Raised in captivity on Planting 437, kitchen-seed Jellybean “Ji-ji” Lottermule knows there is only one way to escape. She must enter the annual Freedom Race as a runner.

Ji-ji and her friends must exhume a survival story rooted in the collective memory of a kidnapped people and conjure the voices of the dead to light their way home.

Pleas enjoy this free excerpt of opens in a new windowThe Freedom Race by Lucinda Roy, on sale now, and check out book 2, opens in a new windowFlying the Coop, on sale 7/5/22!

1: The Cradle

A convulsive wail catapulted Ji-ji awake. Oletto had woken to nurse. The wailing reached a crescendo. Each night her little brother woke at ten and two, guzzled from her mam’s teat like a drunkard, then fell back to sleep so rapidly it looked like he was faking it. Only he wasn’t—not according to Ji-ji’s mam, who welcomed the wailing, said it assured her that her lastborn was still with them. “Don’t ever leave a seedling to purple-wail like that, Ji-ji,” Silapu would warn. “Unanswered yearning can split you wide open, force you to spend the rest of your life searching for foolish ways to plug up the wound.”

Ji-ji rolled over to face the tattered curtain hanging over the doorway that separated her bedroom from the main room. For a few seconds, she tried to convince herself her name wasn’t Jellybean Lottermule. She was Ji-ji Jubilation, the j’s in her first name pronounced like the g in gee whiz. She’d chosen it because it sounded cute and sassy, neither of which she was. “Brown as dung” the steaders called her, nothing like her dark and pretty mam, or Charra, her light-skinned, pretty sister. Not that she gave a damn what dumbass steaders thought. The only name worse than Jellybean was Lottermule. Thinking about it made her want to gag.

Oletto’s wails turned to hiccuping whimpers. Sleep had deserted her, so Ji-ji took refuge in her pretend life. She was living Free! Free! Free! in Dream City . . . or up in the Eastern SuperState maybe, where rumor had it they’d rebuilt some of the iconic skyscrapers, locating them farther back from the coast this time cos SuperStaters didn’t blame floods on the wrath of God like steaders did. She pictured herself living in a penthouse—a term Father-Man Lotter used to describe the main offices of the Territorial Headquarters in the Father-City of Armistice, a.k.a. the City of Cages. (Don’t think about their disgusting capital. It’ll drive you crazy. Go back to where you can live Free. . . .) She found a place of refuge again.

She was a half-Toteppi princess living high on the hog with her mam and little brother in a penthouse hundreds of miles from the Territories. No man could ever touch her or beat her. Ji-ji Jubilation was her very own self on her very own terms. . . .

Her brother’s whimpers turned to shrieks. The truth gnawed like rats, severing the hope-rope she clung to. They weren’t living in a liberty SuperState or an Independent oasis; they were trapped at the butt end of the Old Commonwealth of Virginia on one of the hundreds of plantings homesteaders established following the Civil War Sequel. She was Jellybean Lottermule, chief kitchen-seed. . . . It would never be enough. . . .

Ji-ji grabbed her wristwatch from the small bookshelf Tiro had made for her fourteenth birthday. She’d won the watch in one of the planting races. She stared at the hands on the watch’s face. It was a child’s wind-up watch, which explained why the steaders had given it as a prize to the fastest female runner. A tiny, coal-black cartoon mouse pointed his white-gloved, chubby fingers at the numbers on the watch face. The mouse was grinning so hard it looked painful. He reminded Ji-ji of the black-faced minstrels who played at the barn dance during the Harvesting Festival. Two A.M. Only three more hours to go before her morning run. By six thirty, she’d be preparing Lotter’s breakfast at the father-house. He liked to eat early: poached eggs cooked just right—never hard-set but not undercooked either; coffee smooth not bitter—no milk, no sugar. Father-Man Lotter didn’t go in for diluting anything.

Oletto’s whimpers turned to screams. If she didn’t get an hour or more of sleep she’d be dragging all day. She tried to think of herself as lucky. At fourteen, she was one of the few postpubescent females still living in her mam’s cabin. She recited the words Zaini, Tiro’s mam, had taught her to raise her spirits: “Our mother, which art the Cradle, may we know our hallowed names.” She took a deep breath and blew it out slowly to calm herself, then stepped lightly out of bed. Yawning, she shuffled through the bedroom, careful to avoid the twelve dents in the floor made by the legs of her three lost siblings’ beds. The dents they’d left behind were pretty much all she had to remember them by. Stepping on them would have seemed like blasphemy.

Ji-ji entered the only other room in the cabin. Silapu must have been up for a while because a crackling fireplace warded off the winter chill. Apart from Oletto’s cradle and Lotter’s fancy rocking chair, all their other furniture was junk: a rickety table on a tired rug whose edges curled up like fried bacon; three wobbly wooden chairs, one with part of its back missing; and a sink with a working pump—admittedly a luxury few seed cabins possessed.

Ji-ji glanced over at the one object in the room—apart from her brother’s magnificent cradle, of course—that didn’t make her want to scream. Tiro’s mam Zaini had made the quilt as a grieving gift for Silapu after Luvlydoll died. It depicted blackbirds—three perched in a tree while a few dozen took off from the branches in a burst of something akin to fireworks on the Fourth of July. The quilt almost convinced you the seedmate cabin was home, almost made you forget that behind it was Lotter’s seeding bed. Not that her mam used it much. When Lotter wasn’t paying her a seeding call, Silapu didn’t sleep in the mating bed, opting instead for a makeshift bed on the floor. However hard she scrubbed, she claimed, it was impossible to wash Lotter’s mating stench from the sheets.

Having dragged a chair over from the table, Ji-ji sat down beside the cradle. Woven from twigs fashioned into impossible patterns, it had solid black walnut rockers decorated with intricate carvings of beasts and birds. Six months before, a few hours after her mam had given birth, Uncle Dreg had shown up out of the blue to present Silapu with the magnificent cradle. When Ji-ji had asked him how he’d known her mam had seedbirthed, he’d pointed to his Seeing Eye necklace and smiled the way you do when you want to keep someone guessing. “This cradle will keep your offspring safe,” the wizard had promised.

“Your brother is teething,” Silapu declared with unmistakable pride. “His front tooth is sprouting, see? It is a sharp one. He will start biting down hard when he nurses. You were a biter. . . .”

Ji-ji poked her index finger into Oletto’s mouth—not easy because he was snuffling around for the large dark nipple he craved—and found his wayward tooth. It had put down roots in the middle of his top gum.

“That center tooth is a sign,” Silapu stated. Her Toteppi accent made her sound wise. “My own father’s front tooth was in the center like this one. It is my father come to me again. ‘Same mouth, same words’—that is what we Toteppi say. When this one is a warrior grown, he will sound like my father. His voice will boom out across the bush.”

“We’re not in the bush,” Ji-ji reminded her. “We’re in the Homestead Territories.”

“Only when our eyes are open,” Silapu insisted.

Ji-ji smiled. It was good to hear her mam speak of her homeland, good to see her happy again. Tribalseed “imports” from the Cradle, shipped over to the Territories to address the severe labor shortage, sometimes wasted away or killed themselves soon after they arrived on transport planes or cargo ships. Silapu had been Ji-ji’s age when she’d been snatched from the Cradle by pickers. Her mam knew the old words and the old stories, though unlike Uncle Dreg, she never spoke them aloud. “You know what memories are, Jellybean?” she’d said once to Ji-ji, after Clay had been auctionmarted. “Memories are knives—slice, slice!” She’d slashed her arms through the air and banged her head against the wall until Ji-ji and Charra coaxed her quiet. But tonight, as Silapu looked at her lastborn, there was a deep contentment and a Toteppi pride in her eyes.

“Do you hear that, Bonbon?” Ji-ji asked, suddenly happy. “Mam says all you need to do is keep your eyes shut an’ you won’t even know you’re on a planting.”

Ji-ji loved to use the nickname she’d given her little brother. She’d had a bonbon once—a dark chocolate one. It had slipped down her throat as easy as spit. She wished her lost brother and sisters could have seen him; they would have loved him too. But after metaflu took Luvlydoll, and they shipped Clay off to the auctionmart, and Charra—god knows what happened to Charra—Ji-ji was the only one left. Charra, the last of the three to be lost, had disappeared some months ago. Silapu, who’d been barely holding things together before then, was inconsolable. She blamed herself for what happened, though she wouldn’t tell Ji-ji why. Crazy with grief, she’d drowned her sorrows in cheap whiskey from the planting store and pills she got from Lotter. She hadn’t known she was pregnant until roughly the fifth month. When Doc Riff diagnosed her condition, she swore she’d never touch a drop of booze or swallow another of Lotter’s pills—as long as her offspring was healthy and she was allowed to keep him. She sensed early that her lastborn was a boy, the seedling who would make her life bearable, she said. Silapu and Ji-ji had delivered Bonbon without a midwife or doctor in attendance. Ji-ji suspected her mam had somehow guessed her lastborn’s secret.

When Bonbon slipped out of the seed canal into her hands, Ji-ji had stared at the seedling in disbelief. Unlike Silapu’s other liveborns and deadborns, the infant was Midnight dark. Ji-ji had been “disappointingly dusky” herself, according to Lotter, her complexion aligning more closely with a typical Commonseed’s than a Mule’s. But Lotter reconciled himself to Jellybean’s “dun-colored cheeks and nappy head.” Bonbon’s case was much more extreme, which was why both Ji-ji and her mam were terror-struck when they saw him.

Among Tribalseeds and products of Commonseed matings, very dark complexions were not unusual. Biracial Muleseeds, on the other hand, especially those begat by father-men, were supposed to testify to the strength of the patriarchal seed. Bonbon’s complexion was on the Midnight arc of the official Color Wheel—a number 35 or 36. According to steader doctrine, Muleseeds on the duskiest arc (a.k.a. the cuckold arc) testified to the promiscuity of a seedmate.

Silapu and Ji-ji were thrown into a panic. They debated making a run for it. But how would they scale the electric fence without being fried? Even if they managed it somehow, the planting search hounds would hunt them down, or mutant beasts roaming The Margins would tear them to pieces. Silapu was terrified of the mutant big-cat and wolf species unleashed by the Territories to discourage trespass—an experiment gone hideously wrong. How would she protect her lastborn if they ran into a pride of snarlcats or a pack of stripers?

Ji-ji knew mutants and search hounds weren’t the only horrors they would encounter. Because Uncle Dreg served as an errander for Cropmaster Herring (one of only four seeds on the planting who had a Right to Roam) he’d seen the world outside the 437th and had told her and Tiro how brutal it was, revealing things about his travels that made her blood run cold. She’d also read An Abbreviated History of These Disunited States, a book Miss Zyla Clobershay had given her days before she was fired for teaching things not on the seed curriculum. Though the Sequel had ended decades before, and some parts of the nation were at last beginning to emerge from the chaos created by the Long Warming, the former United States could be hell on earth for seeds.

Fueled by armed militias and taking advantage of the turmoil caused by shifts in climate, all of the Deep South and great swaths of the country’s Midwest had seceded from the union to form the self-governing Homestead Territories. After the Sequel, the Eastern and Western SuperStates and the Homestead Territories had signed an uneasy truce, to the consternation of many urbanites in the Territories who were ready to die rather than submit to Territorial rule. Cities like Atlanta, Chicago, TriCity, Birmingham—and smaller places like Oxford, Mississippi, and Fayetteville, Arkansas—rebelled. In a coordinated effort that took the Territories by surprise, city mayors signed DUIs—Declarations of Urban Independence—broke ties with the Territories, and formed militias of their own. At first, flush with their own success, the Independents had welcomed refugees. But that soon changed when they understood the precariousness of their situation.

What Ji-ji learned from the history book she kept strapped to the underside of her bed refuted everything on the seed curriculum. The United States wasn’t “reformed and revitalized,” as the steaders liked to put it. It was a fractured, jittery nation teetering on the edge of total anarchy.

Ji-ji might have been afraid to tell Silapu the unvarnished truth, but Uncle Dreg had no such reservations. When he’d visited them to deliver the cradle a few hours after Silapu had given birth, he’d also delivered dire warnings about the dangers that awaited them should they try to run (though how he knew they’d been thinking about doing so, neither of them could figure out). He painted an alarming picture: the SuperStates and Independents were turning away hordes of asylum seekers; outbreaks of metaflu, cholera, and malaria had turned the squalid shantytowns that had sprung up around the Independents into death traps. If they made it to Dream City without entry papers, they would join the thousands of other refugees in the No Region. They would live in sight of a Dream they could never enter and a wall they could never climb.

The old wizard had taken Silapu’s hand tenderly in his own. “Place your trust in the Freedom Race,” he’d told her. “And in your courageous offspring. I have never seen another racer fly as fast as your thirdborn. When Ji-ji wins, she will petition for you and the infant.”

In a tone brimming with certainty, Uncle Dreg had told Silapu her lastborn had come to him as a grown Freeman during one of his journeys through future-time. “He stood tall in the Cradle, like your father. His voice echoed across the land. I have also seen Ji-ji in the Window-of-What’s-to-Come, wearing the Freedom Race logo and running like the wind. So you see, Sila. All will be well.”

After Dreg had left, Silapu—no slouch herself when it came to manipulation—said it was ironic that the old wizard had used Ji-ji’s gift as a runner to persuade them not to run. Then she’d said something else that still haunted Ji-ji: “Let us hope we do not regret placing so much faith in your abilities, Jellybean.” Ever since, Ji-ji had thrown herself even more aggressively into her training, often going on late-night runs in addition to predawn ones, running till her feet bled and her heart was a piston in her chest. She was their only hope now; she had to succeed.

Deciding not to make a run for it had meant facing Lotter. In hopes of avoiding him, Silapu hadn’t ventured out during the day, not even to the outhouse, for fear one of Lotter’s parrots would spot her and relay the fact that she’d seedbirthed. On the seventh night, however, without warning, Lotter had barged in like a man possessed. Before they could stop him, he’d snatched up Bonbon and examined him from head to toe, rubbing his thumb over his seedling’s back and shoulders like someone who could erase the blackness completely if he worked at it hard enough. After Lotter had finished rubbing, he’d done something they’d hardly ever seen him do before. He’d laughed—a full-throated guffaw. By this time Ji-ji was certain Lotter was drunk, high, or both. He’d wrapped his seedling carefully in the mushroom-colored seeding quilt Zaini had made and eased himself into his rocking chair. Still chuckling, he’d taken out his pipe and puffed contentedly while he rocked his dusky seed in his fairskin arms, as if Oletto were his Son-Proper instead of his Mule.

“Little bugger’s black as pitch, Mammy Tep,” he’d said, addressing his dumbstruck seedmate. “Black as an import. But pretty as the devil in spite of that. See those big black eyes round as moons? Damn! You ever seen a seedling prettier’n this one?”

Lotter assured his favorite seedmate she could keep her lastborn. Said he’d “figure out the rest later.” It was the first time Ji-ji could remember her mam looking at her father-man with something approaching affection. It had always been the other way around—Lotter needing her so much he’d try to beat the love out of himself by beating her. That’s what her mam said anyhow. Ji-ji wasn’t convinced a selfish bastard like Lotter was capable of loving anyone.

In the six months since Bonbon’s birth, every day had been a celebration. Whenever Bonbon grasped Ji-ji’s Chestnut finger in his Midnight ones, everything felt right.

Ji-ji and Silapu were laughing at Bonbon’s ecstatic gurgling when they heard footsteps outside the rough-hewn wooden door. They knew at once who it was: Lotter making one of his late-night seeding calls. He’d likely be high or drunk. Mean too.

Reluctantly, Silapu placed her sleeping offspring back in his cradle. In his dreams, Bonbon was sucking on an invisible nipple as though his life depended on it.

Ji-ji rose hurriedly. She stood next to the cradle in her flimsy cotton nightshift. Scared the light from the fire behind her would make it see-through, she covered herself with her hands.

Arundale Lotter thrust open the door and stood stock-still in the doorway. His thick blond hair was pulled back, his steader’s beard neatly combed.

Ji-ji was hurrying toward her bedroom when something made her stop dead.

Lotter took one step forward. Usually, when he entered one of his seedmate cabins, he swallowed everything whole; this time something was different. He was hesitant, if she could apply a word like that to a father-man like him. Behind him, the night was pitch-black: no moon, no stars. Lotter stood inside a headstone of gloom. A feeling of dread enveloped her. It’s only the night, she thought, tamping down her sense of foreboding. But the shadows writhing on the uneven walls looked sinister. More sinister still were the shadows licking the rocker Lotter had gone to enormous lengths to have custom-made because he wanted to sit in comfort when he made a seeding call. Neither Mam nor Ji-ji used Lotter’s rocker, unwilling to plant their asses where his had been. Silapu had eaten a late supper; her plate and fork were still on the table. He wouldn’t like that. He liked things clean and put away in their rightful places.

Lotter’s scent wafted toward Ji-ji on night breeze—a lavender-citrus, musky fragrance that preceded him like a warning shot. He had the man-scent shipped all the way from Armistice. It arrived in a brown velvet box whose color would fall squarely in the middle of the Burnt Sienna arc of the Color Wheel, exactly where her mam’s complexion did. In gold calligraphy on the inside of the box was the perfume’s fancy name: Dark Essenceial. Because she hadn’t known any better as a seedling, Ji-ji used to repeat that name to herself, swishing it around in her mouth like spring water on a hot day. Father-Man Lotter was the only one of the thirteen father-men on the 437th who wore scent. Not even Cropmaster Herring—who, like every cropmaster on every planting in the Territories, had the right to lord it over his disciples—indulged in that kind of vanity.

Without warning, two tall men stepped out of the shadows and took up positions on either side of Lotter. Ji-ji recognized them at once. The brute on Lotter’s right went by the name of Vanguard Casper. He was Lotter’s chief overseer—a man of immense height and girth who always, for some inexplicable reason, made Ji-ji think of shovels. Van Casper’s beard reached almost to his waist. The one on Lotter’s left was Matton Longsby, the blond guard only a few years older than Ji-ji, whose beard was more of a promise than a fact. Everyone commented on how much the guard looked like Lotter’s Son-Proper, if he’d had one, which he didn’t. (When drunk or high, Lotter complained to Silapu that his Wife-Proper in Armistice was as frigid as a glacier and as barren as a desert. No point in dragging the bitch down here to the boondocks, he’d say, if she can’t be put to good use.)

Seconds passed. Ji-ji felt panic rise inside her. Everything seemed to be scurrying for the exits—screams, even piss. . . . She held them in, knowing how disgusted Lotter would be if she didn’t.

It was when Lotter turned to give instructions to ’Seer Casper that Ji-ji and her mam saw it. Lotter’s long blond hair was pulled back into a ponytail with a fat black seizure ribbon!

“NO!” Silapu cried. “I kill you if you do this thing!”

To Ji-ji it seemed as though someone had fired a starting pistol. Everything took off running as Silapu leapt toward Lotter, screaming like something on fire. Lotter pushed her roughly to the side. Silapu recovered and flung herself toward the cradle. Casper grabbed her before she could snatch up her seedling.

Ji-ji rushed to help her mam but found herself hoisted off the floor by the blond guard as she kicked and screamed. It was useless. Matton Longsby’s grip was as strong as hope-rope.

Mad with terror, Silapu punched the overseer in the eye. ’Seer Casper reeled back in fury. He came at her again, cinching her so tight round the waist she gasped for breath. Silapu let out a mother’s agonized roar.

Casper yelled at her: “Shut the fuck up, bitch!”

Immediately, the overseer realized his mistake. Still trying to shield himself from Silapu’s crazed attack, he looked over at his boss and began to apologize.

Lotter interrupted him: “Overseer Casper, have eighty rebel dollars in an envelope on my desk by dawn.” No one doled out an eighty-dollar fine for cussing, but Casper knew how foolhardy it would be to argue with a man like Arundale Lotter. “And another thing. You hurt one hair on my seedmate’s head and I will kill you. Is that clear?”

Van Casper, his face a thunderstorm, nodded. The overseer gritted his teeth and held Silapu tight, wincing as her frenzied kicks made contact with his shins. Bonbon was screaming bloody murder. Every seed in Lotter’s quarters and beyond could hear his wails.

When Lotter yanked open the flap of his leather satchel and drew from it a white wooden wheel the size of a dinner plate, Silapu’s agonized cries echoed around the small cabin. Glued at regular intervals along the wheel’s rim were thirty-six color swatches made from small squares of cloth—paler swatches first, followed by light tans, deeper tans, browns, black-browns, and finally the darkest shades of all, on the Coal and Midnight arcs. Bending over the wizard’s beautiful cradle, Father-Man Lotter held the Wheel to the seedling’s face, beginning with the lightest swatches and rotating it until he reached the shade that matched his seedling’s skin color.

He read the official ruling in a tight, emotionless voice: “I, Arundale Lotter, First Father-Man on Planting 437, hereby decree the fifth seedling of botanical Silapu Lotterseedmate to be a number 35 on the Midnight arc of the Color Wheel. He fails to testify to the strength of the patriarchal seed, attesting instead to the hussification of his mam and the blatant disrespect she has shown to myself, her fathermate and benefactor. Accordingly, the seedling will be removed from Planting 437 and shipped to a server camp where he will be raised nameless to serve the Territories as a Cloth-35. May his mam understand the error of her ways. May all who witness her shame be mindful of the authority of the Color Wheel and the divine hierarchy of the Great Ladder.”

Lotter reached back and tore off his seizure ribbon. Set Free, his blond locks cascaded to his shoulders. He picked up Bonbon and draped the black worm of a ribbon round his seedling’s chubby neck. Lotter hadn’t looked at Silapu when he’d read the pronouncement, but he did so now. His handsome face was battered by the firelight; it looked like he was crying. Ji-ji didn’t give a shit if he was. Her mam would never survive this. Might as well put a gun to her head.

Ji-ji tried to utter Bonbon’s name, but she was choking back tears and struggling against the viselike grip of the bastard guard who held her.

Just then, Uncle Dreg arrived with his niece Zaini. Ji-ji knew why Lotter had ordered them to be there. Left to her own devices, Silapu would kill herself.

“Get her out of my sight, Dreg!” Lotter ordered. “Don’t make me whip her quiet.”

Lotter’s voice cracked when he said this. She looked over at Uncle Dreg. He and Zaini were trying and failing to calm Silapu. Using her eyes, Ji-ji pleaded with Uncle Dreg to intervene. Uncle Dreg was an Oziadhee, a Toteppi wizard from the Cradle, the person who’d told her magical stories and fooled her into believing anything was possible. “Please,” she whispered. “Please!” But he only shook his head and said something to her mam in Totepp—some worthless drivel about hope.

Zaini and Uncle Dreg dragged Silapu from the cabin as she called out to Bonbon and flung curses at Lotter, who ordered Casper to escort them safely back to Zaini’s cabin. “Not a hair on her head, Casper—understand?” Lotter warned again.

“Yessir,” Casper said, and followed them out. It took a long time for Silapu’s screams to fade into the night.

“Stay here, Longsby. I’ve sent over to Petrus’ quarters for . . .” Lotter paused. “What’s that Mule’s name? Lua? Sent for her mam too. They’ll be here soon.” He addressed Ji-ji. “Don’t do anything stupid, Jellybean. You’re your mam’s Last&Only now.”

Ji-ji spat at him. The arc of spittle fell short and landed at his feet. If Guard Longsby hadn’t spoken up at that moment, Ji-ji suspected her father-man would have beaten her bloody.

“Let me carry the Serverseed, sir,” Longsby suggested.

Although Lotter had given Bonbon that designation, he looked daggers at the young guard when he uttered the word Serverseed. Lotter, who never cussed in front of his men, said he’d carry his own damn seedling himself. Ji-ji snatched at straws. He’d used the possessive to refer to Bonbon.

Did that mean he wouldn’t issue a Public Condemnation against her mam for whoring? What did it matter either way when he’d already snatched the one person her mam needed to keep on breathing?

Lotter tucked an apoplectic Bonbon under one arm like a bag of cornmeal.

As he stepped into the headstone doorway, Ji-ji made one last plea: “Please, Father-Man! Let me kiss Bonbon goodbye!”

Lotter didn’t seem to know at first who Bonbon was. He glanced down at the screaming seedling as if he couldn’t imagine how he got there. “Oletto you mean? Her lastborn? You want to kiss him?”

Lotter seemed to think about it; then he shook his head. Without another word, he tore out into the gloom.

Her father-man had ripped her arm off. He’d torn open her chest and excised the last sliver of hope. Wrenching herself from the guard’s grip, she fell to her knees, gasping. She would never see her little brother again. Bonbon, the last of her four siblings, was gone.

Copyright © Lucinda Roy 2021

Buy The Freedom Race Here:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

“I didn’t want to write about why the caged bird sings; I wanted to write about how the caged bird flies.” –Lucinda Roy, author of Flying the Coop

“I didn’t want to write about why the caged bird sings; I wanted to write about how the caged bird flies.” –Lucinda Roy, author of Flying the Coop opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

The Freedom Race, Lucinda Roy’s explosive first foray into speculative fiction, is a poignant blend of subjugation, resistance, and hope.

The Freedom Race, Lucinda Roy’s explosive first foray into speculative fiction, is a poignant blend of subjugation, resistance, and hope.

Light From Uncommon Stars

Light From Uncommon Stars Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers and Other Stories

Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers and Other Stories Unconquerable Sun

Unconquerable Sun  Book of Night

Book of Night

The Library of the Dead

The Library of the Dead Alien Day

Alien Day Shadow & Claw

Shadow & Claw Witness for the Dead

Witness for the Dead When the Sparrow Falls

When the Sparrow Falls The Empire’s Ruin

The Empire’s Ruin Joker Moon

Joker Moon The Justice in Revenge

The Justice in Revenge She Who Became the Sun

She Who Became the Sun The Rookery

The Rookery

Neptune

Neptune The Exiled Fleet

The Exiled Fleet The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know Fury of a Demon

Fury of a Demon You Sexy Thing

You Sexy Thing

The Freedom Race, Lucinda Roy’s explosive first foray into speculative fiction, is a poignant blend of subjugation, resistance, and hope. Download a FREE sneak peek today!

The Freedom Race, Lucinda Roy’s explosive first foray into speculative fiction, is a poignant blend of subjugation, resistance, and hope. Download a FREE sneak peek today!

The Helm of Midnight

The Helm of Midnight

Isolate

Isolate The God is Not Willing

The God is Not Willing