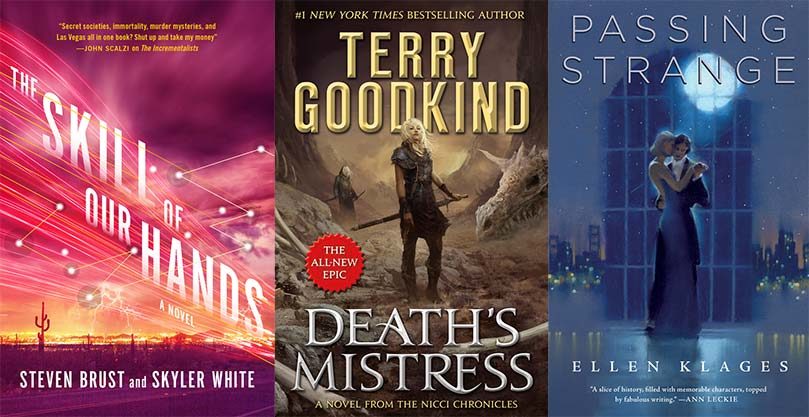

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues today with an extended excerpt from The Incrementalists, a tale of secret societies and immortality from Steven Brust and Skyler White. The next book in this series, The Skill of Our Hands, will become available January 24th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

Welcome back to Fantasy Firsts. Our program continues today with an extended excerpt from The Incrementalists, a tale of secret societies and immortality from Steven Brust and Skyler White. The next book in this series, The Skill of Our Hands, will become available January 24th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

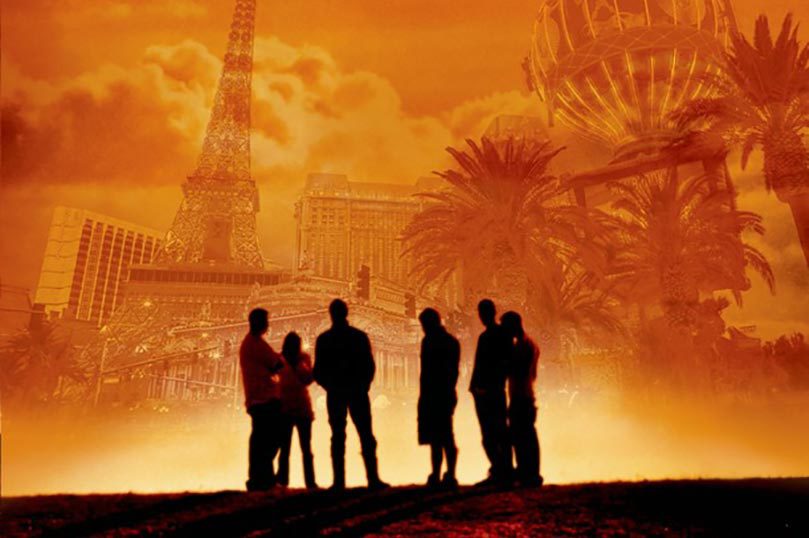

The Incrementalists—a secret society of two hundred people with an unbroken lineage reaching back forty thousand years. They cheat death, share lives and memories, and communicate with one another across nations, races, and time. They have an epic history, an almost magical memory, and a very modest mission: to make the world better, just a little bit at a time. Their ongoing argument about how to do this is older than most of their individual memories.

Phil, whose personality has stayed stable through more incarnations than anyone else’s, has loved Celeste—and argued with her—for most of the last four hundred years. But now Celeste, recently dead, embittered, and very unstable, has changed the rules—not incrementally, and not for the better. Now the heart of the group must gather in Las Vegas to save the Incrementalists, and maybe the world.

ONE

You Entering Anything?

Phil

From: Phil@Incrementalists.org

To: Incrementalists@Incrementalists.org

Subject: Celeste

Tuesday, June 28, 2011 10:03 am GMT – 7

You’ve all been very patient since Celeste died. Thanks. Since no one responded on the forum, I’m asking here before I go ahead: I think I’ve finally settled on a recruit for her stub. If some of you want to look it over, the basic info is the hemp rope coiled on the bottom branch of the oak just west of my back gate.

There. That finished what I had to do; now I could be about earning my living. I put the laptop in its case, left my house, and drove to The Palms. Just like anyone else going to work. Ha.

Greg, the poker room manager, said, “You’re here early, Phil. No two-five, just one-three.”

“That’s fine,” I said. “Put me down for when it starts.”

Greg nodded. He always nodded a little slowly, I think so as not to risk dislodging his hairpiece. “We have an open seat in the onethree if you want it,” he added.

“I’ll wait, thanks. How’s the boat?”

“It’s still being a hole to sink money into. But I should have it working again by August. Going to take the kids out and teach them to run it.”

“Why, so they can burn out the engine again?”

“Don’t even joke about it. But if I ever hope to water-ski, I’m going to have to.…”

Five minutes later I disengaged and went to 24/7, the hotel café, to relax until the game started.

While I waited, I drank coffee and checked my email.

From: Jimmy@Incrementalists.org

To: Phil@Incrementalists.org

Subject: Re: Celeste

Tuesday, June 28, 2011 6:23 pm GMT

Looks good to me, Phil. I have no problem with you going to Arizona to do the interview.

I hit Reply.

From: Phil@Incrementalists.org

To: Jimmy@Incrementalists.org

Subject: Re: Celeste

Tuesday, June 28, 2011 11:26 am GMT – 7

The World Series of Poker is going, so this is a good time for my sugar spoon and a bad time for me to go to Phoenix. Feel like crossing the pond? Or finding someone else to do the 1st interview? I’ll still titan. Or we can put it off a week; there’s no hurry, I suppose.

I hit Send and closed my laptop as I felt someone looming over me.

“Hey, Phil.”

“Hey, Captain.”

Richard Sanderson, all 350 pounds of him, slid into the booth. We’d exchanged a lot of money over the years, but I was glad to see him. He said, “Phil is here before noon. Must be WSOP week.”

“Uh-huh. Which now lasts a month and a half. You entering anything?”

“I tried the fifteen hundred buy-in seven stud and got my ass kicked. That’s all for me. You?”

“No. The side-games are so full of guys steaming from the event, why bother?”

“No shit. I played the fifteen-thirty limit at the Ballaj last night, had three guys who were on tilt before they sat down.”

“Good game?”

“Hell of a good game.”

“How much did you lose?”

“Ha-ha. Took about twelve hundred home.”

“Nice work. Next time that happens, call your buddy.”

“If I ever meet one, I will.”

We bantered a little more until they called him for the one-three no limit game. I opened my laptop again, and Jimmy had already replied, saying that he didn’t feel like going to Phoenix (made sense, seeing as he lives in Paris), but he’d be willing to nudge the recruit to Las Vegas for me. I wrote back saying that’d be great, and asking him to get her to 24/7 at The Palms on Thursday afternoon.

Then I took out my copy of No Limits by Wallace and Stemple and reviewed the section on hand reading until they called my name for the two-five. I bought in for $500 and took seat three. I knew two of the other players but not the rest, because I didn’t usually play this early in the day and because there were a lot of people in town for the WSOP.

I settled in to play, which mostly meant looking at my hand and tossing it away.

I have a house not far from The Palms. I have stayed in many houses, apartments, condos, hotels, boarding rooms, sublets. I’ve lived in many places. But nowhere feels like home quite as much as a poker table. I watched the other players, making mental notes on how they played. I picked up a small pot on an unimproved ace-king, and wondered if the finger-tap from the Asian woman in seat one meant she’d missed the flop.

Sometime in the next couple of days, I was going to see whether Celeste’s stub would work with Renee, and if it did, whether we might have a chance to not tear each other apart and maybe even do a bit of good. That was important; but it wasn’t right now. Right now, it was only odds and cards. And right now is always important.

A couple of hours later, I was all in with two kings against acequeen. The flop came ace-high, and I was already reaching in my pocket for another buy-in when I spiked a king on fourth street and doubled up. I’d have taken it as an omen, but I’m not superstitious.

Ren

From: Liam@GlyphxDesign.com

To: Renee@GlyphxDesign.com

Subject: Meeting with Jorge at RMMD in NYC

Tuesday, June 28, 2011 1:06 pm GMT – 7

Ren, I hate to spring this on you, and I know I said I wouldn’t ask you to travel anymore, but we need you in New York on Friday. The PowerPoint deck looks great, but Jorge has concerns about the audio component of the user interface. I’d like to have you there to field his questions. Get flight details etc from Cindi.

I chose Twix for anger control and Mountain Dew for guts, but nothing in the rows of vending machines between my cubicle and my boss’s office looked like lucky, or even wheedle. I bought Snickers as a bribe, and ate the first Twix bar on the way upstairs.

I poked my head around Liam’s office door, decorated since Memorial Day for the Fourth of July in silver tinsel and tiny plastic flags. He waved me in, tipped so far back in his ergonomic chair that a dentist could have worked comfortably. Liam laughed and said, “I understand,” and “She’s not going to like that,” into his phone headset, and winked at me.

I ate the other Twix bar.

“Okay, let me know. Thanks.” Liam pulled off his headset and waggled his eyebrows in the direction of the Snickers. “Is that for me?”

“Maybe.”

“Because you love me?”

“That depends,” I said, but it didn’t really, and Liam knew it. I slid the candy bar across his empty desk. “Working in a paperless office is different from not working, you know,” I told him.

He grinned and ate half the Snickers in one bite. “I hate to do this to you, I really do.”

“Then don’t. You don’t need me in New York.”

“I’m guessing you have a date for Friday.”

“I’m guessing you’re worried about the cost estimates.”

“It’s an awful lot to propose spending on a feature they didn’t request.”

“They would have written it into the requirements if they bothered to read their own research. I did. They need this. Jesus. Is the air at the top of the corporate ladder so thin it’s killing off brain cells? Don’t either of you remember what happened last time?”

Liam opened the bottom drawer of his desk and produced a giant peanut butter jar full of darts. I scooted my chair out of firing range and shut the door to reveal the big-eyed baby chick in an Easter bonnet Liam had snagged from Cindi’s previous decorating campaign.

“Who’s the guy?” Liam lofted a dart at the pastel grotesque.

“Someone new. He’s making me dinner.”

“I’ll buy you dinner. After the meeting—Eden Sushi, very posh.”

“I’ve had sushi with Jorge before.” I held up my hands like a scale. “Cold fish in bad company. Homemade gnocchi with a hot guy. Gosh, Liam, how’s a girl to choose?”

Easter Chicken suffered a direct hit to her pert tail feathers.

“Move your date to Saturday.”

“Can’t,” I mumbled. “He’s in a band.”

The dart fell onto the carpet as Liam let out a wheezy whoop. “Is the air in your blues clubs so smoky it’s killing off brain cells?” He leaned back in his chair far enough and laughed long enough for a molar extraction. Which I considered providing. “Don’t you remember what happened last time?”

“One bad guitarist boyfriend isn’t a pattern of poor dating choices, but half a million dollars in post-prototype changes should have turned Jorge into a research fetishist. Have you tried just reminding him?”

“He specifically asked me to bring you.”

“Oh, come on.”

“Sorry. But I can’t really say no, can I?”

“What, to your boss? Who would do such a thing?”

From: Cindi@GlyphxDesign.com

To: Renee@GlyphxDesign.com

Subject: Your Flight Info

Tuesday, June 28, 2011 5:46 pm GMT – 7

Hi Ren! Jorge’s PA just called me, and he’s going to Vegas for some poker festival. So guess what?!? So are you! All the Friday AM flights are full, so I bought your ticket for Thursday. You’re staying at The Palms.

Have fun!

There’s just no vending machine voodoo for this sort of day. I went home for ice cream.

Phil

From: Jimmy@Incrementalists.org

To: Phil@Incrementalists.org

Subject: Renee

Wednesday, June 29, 2011 12:49 am GMT

Her flight arrives Thursday early afternoon. She’s got a gift coupon for 24/7 Café bigger than her per diem, but no telling when she’ll use it.

I cashed out around nine, posting a decent win, and went home to log it, check my email, and seed the Will Benson meddlework. I could imagine Oskar being all sarcastic about it: “Great work, Phil. Six dozen signs that won’t use quotation marks for emphasis. That makes the world tons better.” Fuck him. I hate quotation marks used for emphasis.

When I’d finished seeding, I checked our forum and added some noise to an argument that was in danger of acquiring too much signal. Then I watched some TV because I was too brain-dead to read, and much too brain-dead to graze. The Greek unions were striking, Correia beat the Blue Jays in spite of Encarnación’s two homers. I hadn’t recorded the game because no one cares about interleague play except the owners. When I felt like I was going to fall asleep in front of the TV, I turned it off and went to bed.

Wednesday was a good day: poker treated me well, and after a pro forma hour hunting for switches for Acosta, I just relaxed. The most exciting thing on TV was Jeopardy!, so I reread Kerouac’s On the Road. I wish I’d met him. I wish I’d met Neal Cassady. I almost did, once, in San Francisco, but I got into a fender bender at Scott and Lombard and never made it to the party.

From: Jimmy@Incrementalists.org

To: Phil@Incrementalists.org

Subject: Renee!

Thursday, June 30, 2011 3:55 am GMT

Phil, I just happened to come across some of Renee’s background.

What are you trying to pull?

Funny. Jimmy “just happened” to come across some of Renee’s background, like I “just happened” to raise with two aces. And what was he doing up at that hour?

Well, I’d meet her sometime tomorrow, and decide then. When dealing with the group, especially Salt (myself included), it’s easier to get forgiveness than permission. Tomorrow would be a busy day: I needed to talk to Jeff the cook and Kendra the waitress, and I had to prep the café before Renee got in.

I went to bed and dreamed of high seas.

Ren

I couldn’t get the wi-fi in my room to work, but I had a nice apology gift certificate from Liam for the hotel café, so I went downstairs with my netbook and nooked into one of the high-backed booths. I ordered matzo ball soup because I thought it was funny to find it on a casino menu, but I worried about it as soon as the waitress left. Theirs might be good. Maybe even as good as my nana’s, but it didn’t stand a chance against my memory of hers. I flagged the waitress down and changed my order to a veggie burger, which would have offended my grandmother to her beef-loving soul. Then I opened Google Reader.

It was late for lunch and early for dinner, so I had the place mostly to myself when he walked in looking like all the reasons I’ve never wanted to go to Vegas. He wore a ball cap pulled down over predator’s eyes in an innocent face, and I couldn’t tell whether the hunt or the hunted was real. Still, there’s no conversation you want to have with a tall, dark and handsome man who sidles up to your table in the café of a Vegas hotel. I knew better. I put my earbuds in, and I didn’t look up.

“Hi,” he said, like he just thought of it.

I unplugged only my left ear, and slowly, like it hurt me. “Sorry?”

“Hi,” he said again with one of those smiles that means “I play golf!”

“Um, hi.” I touched the molded plastic of the earpiece to my cheek, but he kept a hand on the backrest of the chair beside me. He squatted next to it, graceful on his back foot, bringing us eye-level, and I stowed every detail to bludgeon Liam with.

“I know you’re not looking for company, but when I travel I’m always curious where the locals eat. Just wanted to let you know you’ve found it. There’s no better bowl of soup in town.”

“Good to know,” I said. Liam would actually feel guilty about this.

“But if you want a drinkable cup of coffee, you have to get out of the hotels.”

“I don’t drink coffee.”

“You’ll be okay then, as long as you’re only here a day or two.”

“Because you drive tea-drinkers out of Vegas with pitchforks?”

“Oh, no. We just leave them to starve.” The serious nod that accompanied his starvation of the caffeine-adverse made me laugh. Maybe all the earnest was a game. I was pretty sure I could see a dimple twitching under the edge of his mustache.

“I will leave you alone if you want,” he said. “I’m just talking to you on a theory.”

“What theory is that?”

“That you have absolutely no trouble fending off sleazy pickup attempts, and you like talking to interesting strangers, and you can tell the difference pretty quickly.”

I hesitated. “Okay,” I said. “Any insider tips beyond coffee?”

“Do you gamble?”

“No.”

“Then no.”

“And if I did?”

“I could tell you where not to.”

“And why would you do that? I’m guessing you’re not universally generous with your insights.”

“You might be surprised,” he said, and I caught a whiff of sincerity through a crack in the banter. “But I’d offer you all my secrets, if I thought you’d invite me to sit down. My knees are locking up.”

“Here’s your tea.” The waitress put it down just out of my reach and turned to him. “Get you anything, Phil?”

He glanced at me. Then she did. And whatever anonymous pleasure I’d been getting from a stranger’s privacy in public places seemed like less fun. I shrugged. “Have a seat.”

“Coffee would be great, Kendra.” He stood just slowly enough to make me think his knees ached, and slid into the booth. He told me secrets for eating cheaply and well in Vegas, until the waitress came back with a bowl of matzo ball soup. It wasn’t the sandwich I had ordered, but with its two delicate dumplings floating in a broth that smelled like sick days when Mom had to work and took me to her mother’s, I decided to risk it.

“Shall I let you eat in peace?” he asked, with enough Yiddish inflection to make me check his eyes for a joke.

He smiled at me and, maybe feeling daring because my matzo ball gamble had paid out so tasty, I smiled back. “No, stay,” I said, “and tell me what the locals do here besides eat.”

Phil

I decided that that part had been harder than it should have been. “I’d love to say something clever, like, laugh at tourists. But the fact is, get away from the Strip and locals do the same things they do anywhere else.”

“And in your case, what does that involve?”

“Poker.”

“Just like everywhere else,” she said.

I felt a shrug asking to be let out, but suppressed it. “It sounds more glamorous than user interface design, but when you’re running bad, you miss the steady income.”

There wasn’t even a delay and a double take; she got it instantly. She nailed me in place with her eyes and said, “If you claim that was a lucky guess—”

“Not at all, Ren. Usually, I’d call you Renee until you okayed the nickname, but I know how you hate your dad’s French aspirations.”

She sat back. “Who the hell are you?”

“My name is Phil, and I’m here to recruit you to a very select and special group. The work is almost never dangerous, and best of all we don’t pay anything.”

Her eyes narrowed.

“Yes?” I asked.

“What I’m trying to figure out,” she said slowly, “is why I’m not calling security.”

“I can answer that,” I told her. “Mostly, it’s the soup. It tastes like your grandmother’s. Also, if you listen closely, you can hear Pete Seeger and Ronnie Gilbert singing ‘The Keeper Did A-Hunting Go.’ And if you look behind me—”

“Oxytocin,” she said, staring at me.

I was impressed, and I didn’t mind letting her see it. “Good work. That saves a lot of explanation.”

“You’re triggering memories to make me feel trusting.”

I nodded again. “Just enough to get the explanation in before you have me thrown out. And so you’ll believe the impossible parts at least enough to listen to them.”

“This is crazy.”

“It gets crazier.”

“I can hardly wait. What are the impossible parts?”

“We’ll get there. Let’s start with the merely improbable. Do you like the MP3 format?”

“Huh?” Her brows came together.

“A functional sound format introduced and standardized. Do you think that’s a good thing?”

“Sure.”

“You’re welcome.”

She stared, waiting for me to say more.

“It almost didn’t happen that way. That’s the sort of thing you can do with oxytocin and dopamine and a few words in the right ears.”

She was silent for a little longer, probably trying to decide if she only believed me because I was meddling with her head. Then she said, “Why me?”

“Because you almost got fired for telling truth to power in a particularly insulting way, and you did it for the benefit of a bunch of users you’d never met, and you expected it to cost you a job you liked. That’s the kind of thing we notice. On good days.”

Kendra came by and refilled my coffee, which gave Ren time to decide which of the ten million questions she wanted to ask next. I waited. Her fingernails—short and neatly trimmed—tapped against the teacup in front of her, not in time to the music. Her eyes were deep set and her face narrow, with prominent cheekbones that made me think American Indian somewhere in her background. Her brows formed a dark tilde, her nose was small and straight, and her lips were kissably inviting and led to creases at the corners of her mouth that acted as counterpoints to the laugh lines around her eyes. I wondered what a full-on smile would look like.

“Jesus Christ,” she said.

“He wasn’t one of us,” I told her. “I’d remember.”

Ren

Somehow, to my list of bad habits, I had recently added the practice of tapping my eyebrow with my index finger like an overgrown Pooh Bear with his absurd think, think, think. I caught myself at it and balled my fingers into a fist. Phil had his long body draped casually in his seat, but it stayed taut somehow anyway. He reminded me of a juggler, with his large hands and concentration. “Are you hitting on me?” I asked.

He laughed and relaxed. “No,” he said, and I trusted him.

“Just checking.” I sliced into a matzo ball with the edge of my spoon. “Because guys who ask to join me in restaurants, and make small talk, and recommend soups, and invite me into secret societies are usually after something.”

“I didn’t say I wasn’t.”

That shut me up. I ate some soup and pretended to be thinking. But mostly I was just drifting on chicken fat and memories. Eating hot soup in a cold café in the desert felt a long way from my grandmother’s house. “My, what big eyes you have,” I muttered.

Phil frowned.

“Little Red Riding Hood,” I explained, but it didn’t help. “I’m feeling like I’ve strayed from the path in the woods.”

“Been led astray?” he asked.

“Maybe just led. How did you know to find me in Vegas?”

“We arranged for you to be here. Sorry about your date with Brian. But if he has any sense, he’ll be waiting for you.”

“Is my boss one of your guys, or Jorge?”

“No. But one of us helped one of Jorge’s daughters a few years back, so it wasn’t hard to arrange.”

“So you have people in Vegas and New York. Where else?”

“Everywhere. Worldwide.”

“Phoenix?”

“Not yet.” His cheesy wink reminded me of the parrot in Treasure Island, the way source material seems clichéd when you don’t encounter it first.

“Why Vegas? Is the organization headquartered here?”

His laugh startled me, and made me smile, which startled me more. “No,” he said. “There are only around two hundred of us. I’m the only one out here.”

“So they brought me to you, specifically.”

“Right.” There was not a whisper left of his smile.

“You couldn’t have come to me?”

“The World Series of Poker makes this a bad time for me to leave Las Vegas.”

“So you wanted me enough to screw up my life in a couple of directions, but not enough to miss any poker?”

“Well, it’s not just ‘any poker.’ It’s the WSOP, but I would have come to Phoenix for you if I’d needed to.”

“Why?”

“I already told you.”

“No, you told me why me. Now I’m asking why you.”

Phil put down his coffee cup. It made no sound when it touched the table. “I can’t tell you that.”

“You arranged for me to be where I am. You planned how you would approach me, what I’d eat—no matter what I ordered—and what music would be playing in the background.”

“Yes.”

I listened again. Sam Cooke. Family washing-up after dinner music—energetic, but safe. “And you’ve been manipulating me ever since.”

“That’s right.”

“Manipulating me really, really well.”

He inclined his head in something between a polite nod and a wary bow.

“I want to know how you do that.”

His smile came slowly, but he meant every fraction of it. “That’s what I’m offering,” he said.

“You and this small but influential, international, nonpaying, not-dangerous secret society of yours?”

“Right.”

“Like the mafia, only with all the cannoli and none of the crime.”

“Well, we’re much older.”

“An older, slower mafia.”

He looked a little disconcerted.

“And you fight evil? Control the government? Are our secret alien overlords?”

“Try to make the world a little better.”

“Seriously?”

“Just a little better.”

“An older, slower, nicer mafia?”

He stood up. “There’s substantially more to us than that. For example, most people can’t get Internet in the café. I’ve gotten about half the shockers out of the way, and next time we talk I won’t be meddling with your head. Sleep on it.” He took a small plastic dragon from his pocket and put it by my plate.

“I used to collect these things!” I said. “But you knew that, didn’t you?”

Kendra the waitress stopped him on the way out, said something to him, kissed his cheek, and came to clear our table with her face still pink. I put my earphones back in and logged into Gmail using the wi-fi you can’t get in the 24/7 Café to find two messages waiting for me.

From: Liam@GlyphxDesign.com

To: Renee@GlyphxDesign.com

Subject: Tomorrow’s Meeting Rescheduled

Thursday, June 30, 2011 5:46 pm GMT – 7

Hi Ren,

Hope you’re enjoying Vegas. Jorge has pushed our meeting back. Something came up for him at home, so you have an extra day of fun in the sun on our nickel. Take yourself to a show or something. My flight is the same time, but on Saturday now instead of tomorrow. Sorry, but I know you can entertain yourself.

L.

and

From: Phil@Incrementalists.org

To: Renee@GlyphxDesign.com

Subject: Breakfast?

Thursday, June 30, 2011 5:01 pm GMT – 7

Assuming you’re free.

And somehow, as trapped and arranged and manipulated as it all felt, I knew I was.

TWO

You Can Do That?

Phil

Usually, the first interview without switches is the tricky one, so after yesterday, I was wary. I got to the café first, on the theory that her walking up to me would be less threatening than the reverse. Ren normally woke up at eight and spent forty- fi ve minutes getting ready, subtract fi fteen minutes for her being out of town, giving us 8:30; I arrived at 8:20. Katy was hostessing, and she had a dramatic fake coronary, while making comments about seeing me before noon.

“I’m meeting someone,” I said. “So two, please.”

She led the way, remarking, “It can’t be business, so it must be personal. A girl?”

“She is certainly female, and this has nothing to do with poker.”

“Well, my my.”

“Tell me how your heart is now broken.”

“Not mine, but I can think of a couple of waitresses who will be disappointed.”

“Katy, why don’t you tell me this stuff when it will do me some good?”

“Looking out for my staff,” she said.

“I think I won’t ask what you mean by that. Here she is. Katy, this is Ren.”

“You know everyone here, don’t you?” she said, sliding into a chair. “Hello, Katy.” Ren was wearing pants and a sleeveless green sweater that would have looked purely professional if they hadn’t been tight.

“Enjoy your breakfast,” said Katy and went back to her post.

“She thinks we’re involved, doesn’t she?”

“She’s a doll, but she has a limited imagination. And you are every bit as observant as I’d been led to believe.”

A waiter named Sam came up, looking like the dancer he probably was. I ordered a Santa Fe Breakfast Wrap and coffee. Ren looked at me. I said, “It’s all you, this time.” She nodded and ordered Frosted Flakes and tea.

The instant Sam walked away, she said, “What qualifies as better?”

“We argue about that a lot.”

“What are your criteria?”

“That’s part of the same argument.”

“Okay, who gives the green lights?”

“For meddlework? Usually—”

“Metal-work?”

“Meddlework. Two d’s. Our term for it. Like what I did to you yesterday. Meddling with someone’s head so you can change his actions. Usually no one has to approve, you just do it. If it’s something big, you’re expected to run it past the group fi rst, and people usually do. When they don’t we scream at them a lot. There’s a group called Salt that sort of oversees the discussions but has no real power.”

Her stare was intense. Her mouth was set in a firm line, and her hands weren’t moving at all.

“What if you’re wrong,” she said. “What if you do something big, and it makes things worse?”

There is a curving boulevard that leads to a half- moon–shaped park. Buddha watches over the street at various points. The park is dominated by a curved colonnade that looks more Greek than Asian. Along the boulevard, in the park, on the shiny, glittering street, bodies of men and women, boys and girls, old people and infants, wait to be buried. They’ve all been murdered, but not here; there is no blood in the street; everything is neat and clean, except for the bullet holes. There are thousands upon thousands of dead, and they are all looking at me.

“That can happen,” I finally said. “It really, really sucks. We try not to do that.”

Ren

Trouble moved over his face, lining the edge of his brow and cheekbone like a felt-tip pen. It aged him and put depth under the handsome. It made me want to touch him, but of course he would know the sexy of vulnerable, and I wasn’t falling for that. I had questions.

“How long can you keep me here?”

“Do you want to go?”

“I mean how long can you keep me in Vegas, Liam in Phoenix, Jorge in New York, and RMMD paying for it all?”

“We have time.”

“How do you know? And how can you possibly track all the implications of what you do? You make it so I’m here because this is where you need me, but maybe Brian is my soul mate, and while I’m gone, he meets some other girl and they fall in love.”

“He’s not your soul mate.” Something fi erce in Phil’s calm voice made me wonder whether it was soul mates or Brians he was so certain of.

“I meant as an example,” I said. “Maybe Jorge goes ahead and commits to a design without hearing from us first, and we lose the auditory prompts his own research demonstrates his users need, and a bunch of old people don’t get reminders to take their medicine?”

“Or maybe you join us and I show you how to get even more effective alarms written into the requirements, plus maybe shift Jorge’s priorities a little.”

“You can do that?”

“You can do that. You’re designing a monitoring and assistance device for Alzheimer’s patients. Maybe Jorge’s mom would be interested in joining the beta test pool.”

“That’s what you do? You get nonhuman corporate entities to make decisions on a human level?”

One of Phil’s eyebrows contracted in a way that, if both had done it, it would have been a grimace. Somehow it conveyed interest. “That’s one thing we can do. Sometimes.”

“Sometimes? What determines whether you can do it?”

“Lots of things. How drastic the change is, how well we know the Focus— the person we’re trying to meddle with, how good we are at meddling. No one is going to turn Rupert Murdoch into a liberal, but a few nudges might convince some British investigators to follow up on what he’s doing, if they’re inclined in that direction anyway.”

“That was you?”

“Someday I’ll tell you what we didn’t do. It would have been big. And ugly.”

“So if I want in, what do I do? Confi rmation class? Dunk in the river? Prick my finger?”

“You come home with me.”

“And?”

“You come home with me and find out.”

Phil

Something closed up behind her face. It was as if she suspected the process would be unpleasant, and I didn’t want to tell her about it. Or maybe I just imagined that because it was and I didn’t. On the other hand, maybe she just thought I was hitting on her, and really, I wouldn’t blame me if I did. In an attempt to undo the damage, I said, “Not right now. You can take as much time as you want to think about it. And I’m not meddling with you.”

“I know you’re not,” she said. Then, “But I don’t know who you are.”

“Me, or the group?”

“You. Who are you?”

“That’s a hard question to answer. For anyone. How would you answer it?” She nodded slowly. The food arrived, and Sam asked something about it, and I answered. We ate for a little while, and I drank coffee. Then she said, “What’s the most important thing you aren’t telling me?”

“Good question, but an easy one,” I said. “Because it’s the next thing we get to. The big one. The one you need to know before decid—”

“Just say it,” she said. “I hate prologues.”

I knew that. “The process involves giving you the memories of one of us— of someone who died. No, don’t ask how that’s done. Later. The point is, you’ll be getting the memories of a woman named Celeste. You’ll be what we call her Second, with all of her memories, in addition to all of your own. Which brings up the question of—”

“Who will I be?”

“Exactly.”

“What’s the answer?”

“There’s no way to know.”

She put her teacup down and looked at me. “Oh, well, that’s just peachy. It isn’t dangerous, but for all intents and purposes, I could just disappear?”

“Your memories won’t.”

“But I might.”

I nodded.

“And I should even consider this— why?”

“That whole thing about making a difference. Don’t tell me that isn’t important to you; I know better.”

She said slowly and distinctly, “Shit,” pronouncing it very carefully as if to make sure there would be no confusion.

I ate some more wrap and drank some coffee.

“Who was Celeste?”

I felt my face do something, and it was like I’d just let my eyes widen after flopping quads. Crap. The chances she’d missed it were zero, so I said, “She was someone who was very important to me.”

“You were lovers?”

“Only briefl y in this lifetime.”

“Jesus Christ,” she said. “This lifetime? How many lifetimes have you had?”

“I do not,” I said, “wish to answer that question at this time.”

“I kind of think you should,” she said.

“You are risking what is left of this lifetime. You may, as you, gain others. You may not. There’s—”

“How old are you?” I shook my head.

“That’s an impossible question. This thing I’m asking you to do, where you get someone’s memories. I’ve done that before. So, do you mean the age of this body? The age of my personality? How long the original—”

“Stop it. How long have you been you?”

I inhaled and let my breath out slowly. And I wondered why I was getting upset. This was predictable; part of the normal process. Why was it getting to me this time? One plus zero is one. One plus one is two. Two plus one is three. Three plus two is five. Five plus three is eight. I got up to 610 and said, “I’ve been around for about two thousand years. What else would you like to know?”

“Two thousand years?”

“Me, as me, yes.”

“Do you have memories from before that?”

“Yes, all the way back to the beginning. But—”

“The beginning of what?”

No way around it. “The human race,” I said.

She stared at me.

I continued as if it were no big deal. “But the ones way back are, well, hazy. I can refresh any of them I want to.”

This was where part of her would be saying, All right, just pretend you believe it, and go from there; worry about reality later. “But you’ve been Phil for two thousand years.”

“Two thousand and six, yes.”

“Same personality?”

“Same basic personality. It alters some with the body you’re put in. My personality in a woman’s body is subtly different, and things like sexual orientation are, in part, wired into the brain, so that changes. But I’ve thought of myself as Phil for, yeah, about two thousand years.”

“You’ve been a woman?”

“Several times.”

“Why did you pick a man this time?”

“We don’t get to pick. The others pick for you. That’s why it’s me talking to you instead of Celeste.”

She sat there for a long time, fi rst looking at me, then through me. Then she said, “Is it worth it?”

I discarded half a dozen glib answers, then realized that without them I didn’t know what to say. “That’s sort of an impossible question,” I said. “For me, it’s worth it, yeah. Even with— even with the times we blew it. Was it worth it for you to tell your boss he made Bill Gates look like Richard Stallman?”

Her face twisted up as she tried not to laugh. “You know about that, huh?”

I grinned at her, and she let herself smile. I was right about wanting to see it.

Then she said, “Meddlework. That’s what you call it?”

“Yes. What about it?”

“You do that to people, and change them, to make things better.”

“Yes.”

“I want to watch you do one,” she said.

Ren

“Look how stupid this is.” I held the passenger door open while Phil moved bags of clothes and boxes of paper from the front seat of his Prius. “Car manufactures know even married people drive alone more frequently than with a passenger, but we still have cars with five seats and no storage. If this seat simply folded flat easily, think how much better it’d be for you.”

“But not for you,” he said with a flourish indicating the cleared seat.

“But you almost never have anyone else in here, so most of the time, it’d be better.”

Phil turned his oddly twisted eyebrows to me and I felt stupid. He’d rather have a regular passenger. Obviously.

“It’s just bad design,” I said.

He pointed his eyebrows at the windshield and pulled into traffic.

“The car, I mean,” I said. “How long were you and Celeste together?”

“A while.”

I stopped talking. It seemed prudent. We drove in the quiet through the visual noise of Las Vegas. It faded quickly into a suburban west that could have been Phoenix or Houston or here.

“I can show you the file I’m building for a guy named Acosta, but I’m still gathering switches, so there’s not much to watch yet.”

“Switches?”

“Information I can use to get past his defenses. Like your matzo ball soup. I’m still collecting them.”

“But you can show me one?”

His mouth smiled, but not his eyebrows. “Switches aren’t something you can see. They’re not actual toggles or whips. They’re metaphorical.”

“So you just remember them?”

“Sorta. We store them in the Garden.”

I just waited.

“The Garden is … um. We have forty thousand years of individual memories times two-hundred-odd minds, plus switches and other information. We have to keep it somewhere. The Garden is what we call that somewhere.”

“Somewhere outside yourself?” I asked. “You can store your memories remotely?”

“Sorta,” he said. “It’s hard to explain. But in effect, yeah. You’ll either understand when you need to, or you won’t need to.”

His house was small, but bigger than a man living alone needs, with a rock yard he didn’t care about and room for two cars. Inside, the emptiness felt Zen more than lonely, and comfortable.

“I know you don’t drink coffee, but I haven’t bought tea for you yet. Can I get you anything else?”

“You weren’t expecting me to come home with you today?”

“No. Most people need to think it over.”

“That’s what I’m doing.”

“No, you’re experimenting with it.”

“I’d take a beer.”

Not just the one, but both eyebrows spun out. “Now you’re just fucking with me,” he said.

“Yeah,” I agreed, and made myself cozy on his sofa. “Tell me about Acosta.”

“One of our pattern shamans tipped us off to him.” Phil stayed in the kitchen, making coffee, getting me a glass of water, talking while he worked. “He’s sales manager at a midsized manufacturing company here in town but moving up the ranks. He started on the line. Couple of months back, he hired a new sales guy, but he’s not working out. Acosta’s given him every chance. He’s loaned him money, covered for him. They’re friends. But now he has to fire him.” Phil hesitated with his hand on the fridge door, back to me, looking for words. “What Acosta ends up telling himself about this—that he can’t be a boss and be a friend, that his buddy’s been trying to play him, or was never really his friend—will make a difference in how he manages everyone else for as long as he works—and we think that’s likely to be a lot of folks. He’s teaching himself a basic rule here, and I want to help it be a good one.”

“How can you know it’s that pivotal?” I took the water from him and he sat down with his coffee cup beside me on the sofa.

“We’ve learned to spot that in people,” he said. “When lives are at a turning point.”

“By comparing your collective experience of people over so much time?”

“Right,” he said.

“Shared in the Garden?”

“Yeah. Shoulders and backs show you what they’re going through is big; their hands tell you it’s urgent; and the jawline lets you know if it’s temporary and immediate or a true pivot point.”

“Do you see that in me?”

He looked at me. “No.”

“You said you’re responsible for the MP3 format.”

“We helped.”

“What else?”

“Excuse me?”

“What else have you done?”

He opened his mouth, then closed it again. “Are you asking for an example, or an exhaustive list? If you want the list, I have to decline; I have plans for next February.”

“An example would be nice. Something like the MP3 thing, where you did something that had a broad effect.”

He was quiet for a few minutes, then he nodded.

Phil

“All right,” I said. “Ever heard of John Rawlins?”

She shook her head, her eyes narrowed and focused on me the way a snake focuses on a bird.

“He was Grant’s chief of staff.”

“Grant? General Grant?”

“Right. The one buried in Grant’s Tomb. What do you know about him?”

“Um. Lee surrendered to him?”

“Right. What else?”

“He was a butcher, a bad president, and a drunk.”

“Yeah, that’s the guy. Except none of those are true.”

She started to speak, and I held my hand up. “The drinking thing. I don’t know, maybe. But he probably never got drunk during the war, and certainly never when it mattered.”

“Then how did he get the reputation?”

“Short version: jealousy in the officer corps, and the fact that he did have a drinking problem when he was in the army after the Mexican War.”

“He beat it?”

“With help from John Rawlins, who took it upon himself to make sure Grant stayed sober.”

She nodded. “And?”

I remembered the flag of the 46th Ohio, tattered and shredded. I remembered myself, after Shiloh, retching from the smell of bodies and saying over and over to myself, You didn’t run, you didn’t run. I remembered huddling on the ground after the second assault on Vicksburg, thinking about the last screaming fight with Celeste and half hoping I’d get a wound so brutal it’d force some sympathy out of her. I remembered the long, ugly march to Tennessee, trying to get a song started and failing as the cold and wet and the mountain paths almost did what even Johnston couldn’t.

“Yeah,” I said. “We saw how important Grant was after Donnelson. We didn’t know if he’d start drinking, but we couldn’t be sure he wouldn’t.”

“So you meddled with him?”

“No,” I said. “With Rawlins. You could say Rawlins meddled with Grant, though he wasn’t one of us.”

“I’m not sure what you’re saying.”

“I found Rawlins’s switches—oysters, saddle-leather, I don’t remember what else. I meddled with him to make sure he took it upon himself to keep Grant from drinking.”

“And if you hadn’t done that?”

“Who knows. Maybe nothing. Or maybe Grant would have been drunk at Shiloh. One thing I know for sure: if the Union had lost at Shiloh, things would have been even worse.”

“So you made him better.”

“I think so, yes.”

She frowned. “But everyone remembers him worse. Why don’t you set the record straight?”

“How would we do that? We meddle a bit with biographers and historians and archeologists, and point them toward evidence, but other than that, what can we do? Who’d believe us? If someone announced, without evidence, that half the books destroyed in the library at Alexandria were works of erotica, would you believe him?”

“Were they?”

“Not half.”

“So there’s nothing you can do?”

That stopped me. The question was either too big or too small. After some thought, I said, “You know what we call people who aren’t one of us?”

“I didn’t know there was a term for them.”

“Of course there’s a term for them. Every group has a term for outsiders. We call them, ’those who forget.’”

“What’s your point?”

“That we remember.”

She was quiet for a couple of minutes. Her shoulders shifted back a little, and she rolled her head as if her neck was stiff.

“That’s it,” I said.

Ren

“In my jaw and shoulders?”

He nodded. “And your hands.” And he was right.

“Can you guys find a nice girl for Brian? Maybe someone a little more rock ‘n’ roll than me?”

“We could, but so could you.”

“Oh, right. I can’t tell anyone, can I? I can’t call my mom and say good-bye?”

“No.” He held my eyes the way you’d take a sick man’s hand. “But you won’t just vanish. Even if your personality doesn’t stay on top of Celeste’s—the other, older personality—it’ll be a meld more than a swallow. And gradual.”

“But I will always be there in the external Garden? Just packed away, stored remotely?”

“Your memories will be.”

“Okay,” I said.

“Okay what?”

“Okay I want in. Whatever it is you have to do to make me one of you. I’m ready.”

“Okay,” he said, and put his coffee down.

THREE

That’s Backwards Too

Phil

Ritual and memory; pain and understanding.

Ritual has a mass, a weight, a gravity. It pulls you into itself, and as you use it, it uses you. It takes power and it gives power. Ritual is the same every time, otherwise it isn’t ritual. It is different every time, otherwise it has no power. No matter how many times we experience the same ritual, it transpires differently than it lives in our memories.

That’s especially true of the ritual I performed on and with Ren, because we never remember any of the details between reaching into the Garden to shape the stub, and using the stub in its new shape. Here, of all places, as part of the ritual, our memory fails.

What is memory? Some say our memories are ourselves, which is oversimplified, but not wrong. But if there were a symbol of memory, what would it be? Would it be wood that came from a living thing as our memories continue to grow and change after the events that created them have passed? Would it be shaped by a human hand as our personalities are shaped by our experiences? Would the shape be pointed, to represent that we are always moving forward? Would it be on fire to represent the memories of passion without which we aren’t human, and leaving behind ash to represent the memories of regret, without which we shouldn’t be?

That’s just rationalization, though. I don’t know why memory is symbolized as a burning wooden spike. But it is, and it always has been, for any useful definition of always.

I finished around nine in the evening, Ren sleeping comfortably on my bed. I pulled a chair up next to her, exhausted by the ritual as always, unable to sleep afterward as always. See previous remark about “always.” I waited, rested, read some Ashbless poems, and wished I could sleep. The Pirates were playing Toronto again, but I couldn’t summon up the energy to check the score.

About three hours later she woke as we always do, a scream starting on her lips continuing the one that almost passed before; then she realized that the only pain was a dull headache, and so the scream never emerged. Then she brought a hand to her forehead, touching it to see if there was a wound. It was a gesture I’d seen thousands of time, and made hundreds.

Eventually, her eyes focused on me: fear, anger, wonderment, confusion. What had I just done to her? How much of it was real? Did it matter if it was real? Why hadn’t I told her what I was going to do?

And then, as I watched her eyes, I could see the first taste of Celeste reaching her. I knew that the strongest, sharpest, clearest of Celeste’s memories would first seep into Ren’s head like floodwater under the door. She’d remember when Celeste went through the same ritual, and perhaps she’d remember when Celeste did the same thing to me. Maybe. I can’t reach Celeste’s memory, except through Celeste. We can’t reach anyone’s memory, except through what they tell us. We trust our memories even though they lie, and we cherish our memories, even though there are some we wish we could scrub like burnt egg off a frying pan.

The memory of pain would be present, clear, sharp, but behind it would be understanding. Pain and understanding are always at war with each other. We are fighters for understanding, but we can only get there through pain. We are keepers of memory, but we can only get there through ritual.

Her eyes focused a little more. I got up, sat down on the edge of the bed, and held a glass of water to her lips. She drank a sip.

“Hello, Ren,” I said. “Welcome back. How’s the head?”

Ren

“You asshole,” I said, which tightened the tenderness I’d seen softening the edges of his eyes enough to keep me from crying. “You shoved a burning stake between my eyes, how the hell do you think my head is?”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “It’s the only way.”

“Jesus Christ. In how many thousand years of evolution, that’s the best you can manage? Talk about a terrible user interface.”

“Something for you to work on, then.” But the tiny lines beside his eyes had gone from care to patience, and now cracked into smile. “But you should eat something first,” he said. “Are you hungry?”

I had to think about it. My body, arranged politely in the dead center of his bed seemed further away than the Renaissance. “Yeah,” I said. “I think so. Got any lark’s tongue in aspic?”

He grinned. “I’ll go check.” He stood up, and I panicked. Without his weight on the mattress, I felt like I might float off the bed. “I know I’ve got peanut butter and jelly,” he said.

My field of vision opened to include both of us, him standing, me on the bed lying rigid, the Ikea furniture and the clean tile floor. “And frozen pizza,” he said. But I was falling out of a well backwards, away from the confines and claustrophobia, and into something much worse. He put a receipt in the open page of the book and closed it.

“Or we could order in,” he said. “You can get almost anything delivered.” He turned back to me, and both of us were small and distant. “Really. Almost anything. Except, for some reason, pizza. You can’t get pizza late at night in Las Vegas. Is that weird, or what?” I could see his living room too, and the kitchen, the little yard in back with a palm tree. “Are you okay?”

If I blinked I would lose sight of us altogether in the weave of bungalows and sidewalks.

“Ren?” He touched my arm.

“Ren?” His fingers closed over my shoulder and trapped the whole suburban block between his palm and my skin. He was sitting, leaning over me, trying to see into my eyes. I let his come into focus. Brown with flecks of something lighter–yellow, or gold maybe, almost amber, and concern. No, worry.

“Peanut butter and jelly, dear chef?” my voice said. “Do not a gas-flame stove and electrical refrigeration and every modern contraption invented to make the preservation and preparation of food into a trivial act or an outrageous hobby now attend your pleasure, where once the collection and preparation of food occupied you so utterly that you scarcely netted even the calories it cost to fell and section meat and wood? Where even the simplest grains and meanest, hard apples were once daily defended from spoilage and rot, frost-burn and rodents, do not now apples from Oregon, oranges from Florida, and bananas from Mexico all await you at the mini-mart you pass before you reach the grocery store in whose vast and air-cooled domain everything from pork loin to fish eggs now stand packed in glass or wrapped in cellophane to be eaten by their expiration dates or thrown away? Yet with all of this—all this splendor, all this wanton excess, you offer me either pizza, knowing I abhor it, or crushed peanuts and squashed strawberries mashed between two slabs of something that bears no more resemblance to bread than this flat futon does to a feather mattress. Having, only hours hence, seared me, cursed me yet again, and impaled me upon the tip of your flaming stake, you now offer to feed me on children’s food?”

“Oh, hello Celeste,” Phil said. “I have good bread. From a bakery.”

“Fuck off.”

Phil’s mouth twisted into a screamlike shape. With a snarl of warning or rage or despair, his hand spanned the back of my head nearly ear to ear. He kissed me. And when he took his mouth from mine, he held my head still, our temples pressed together. I felt his shoulders shake. “I loved you,” he said, choked.

“You should quit smoking.” My voice was tart.

“I did.”

“Not this lifetime.”

“I never started this lifetime. Celeste—”

“I loved you too,” she said, but I didn’t believe her.

Phil was quiet a long time. I watched the hairless little hollow where his collarbones met and tried to remember what the big deal was about peanut butter.

“I’m sorry you had to see that, Ren.” Phil stood up and walked to the bedroom’s little window. He shoved the curtains back and looked into the yard like it’d better not have anything to say about it.

“Maybe we should go with pizza,” I said.

He looked back suddenly and caught me testing the skin of my lips for razor burn.

“I’m sorry about that too,” he said, very quietly.

I shrugged and swung my legs over the side of the bed. “Will Celeste keep doing that?” I asked him. “Just talking out of my mouth that way? She’s kind of long-winded.”

Phil’s face ran through a range emotions. “I don’t know,” he said.

“Do you want her to?”

He held his hands out and I took them. I stood up slowly, but it still ground the headache tighter.

“Pepperoni or Deluxe?” he said.

Phil

You’re always sleepy and hungry as a new Second; you’re always sleepy and jumpy as a new titan. Ren managed some pizza and then fell asleep. I opened my laptop, disposed of email, and seeded the ritual, leaving it as a bright blue flower in a vase just inside the front gate. I looked around while I was there; a knee-high statue of Iupiter stood next to a full-sized brick oven, and on top of the oven was a basket holding six loaves of bread; and just past that were three coils of hemp, followed by nine or ten candles. I didn’t bother looking in the other direction; I was going to need to clean the place up or I’d be unable to graze my own Garden.

Not now, though. Now I had to deal with a new Second, and, dammit, I was missing all the WSOP side action. I’d expected to do the interview, then leave Ren to think about it for a week or two.

I leaned against the wall that existed in my mind and rubbed a virtual hand over a symbolic cheek. Why hadn’t she had to think about it? I walked over to the oven and grabbed the second loaf, ripped off a hunk, and started eating it. The loaf remained in the basket because that’s how things work. I swallowed, and the memory became part of me and I examined it.

She’d been one of those precocious children who pronounce words wrong because she’d read them before hearing them, but it had bothered her more than most, and as a teenager she’d taken to reading with an online dictionary open so she could hear the pronunciation of words she didn’t know. Interesting, but so?

I bit into the next loaf of bread and recalled how she’d gotten into user interface, and how angry she got over poor design, and realized that she took bad design as a personal insult directed at everyone who used it. Again, interesting, but so?

I continued, and got nothing; but, as so often happens, the accumulation of little things built up an obvious answer so gradually that it had been sitting in front of me for some time before I realized it: She hadn’t hesitated, because there was something she wanted to do. She had an agenda I hadn’t seen.

And I was her titan—responsible for her and it, whatever it was.

Crap.

I let the Garden dissolve around me and there I was, shaking and in desperate need of the pizza that was all the way across the room. According to the clock on my laptop, I’d spent more than two hours grazing.

I ate cold pizza, then threw myself onto the couch.

I was going to have a lot to talk to Ren about when she woke up.

Ren

I woke up happy, with the heavy-boned tired you get from swimming all afternoon in a summer lake. Easy, and not wanting to hurry back to the real world—whatever that means when half my work and all my correspondence exist only electronically. After pizza, I’d stripped down to my skivvies and crawled into Phil’s bed. Now I dove back out of it and dug through the pile of my clothes for my phone, but a short message from Cindi settled me down. Phil—or someone in the Big Power Tiny Action organization I’d just joined—had jiggered things overnight to keep me in Vegas and Liam in Phoenix through the rest of the weekend at least. A longer note from Liam apologized a lot and promised to make it up to me. I sat back down on Phil’s bed and pondered whether I could fit out his window. Head first or feet? Shoulders stuck in the opening or ass wedged in the wall?

Not like he—they—couldn’t find me, even if I managed to squeeze through. Where would I go? And it wasn’t really Phil I wanted to flee, just everything I’d seen while I slept, and what it all meant.

I stood up and stretched. Celeste had been right about the futon mattress—it was unforgivingly firm. I wanted a shower and clean clothes and decent food and time to think it all over. I settled for Phil’s vintage bathrobe of white-and-blue, striped cotton, soft enough to make me wonder if Celeste had a stash of favorite clothes hidden for me, and if they’d fit, and whether she would have been prettier in them.

I tip-toed past Phil, sprawled on his sofa, looking more poleaxed than asleep, one arm thrown over his eyes, the other fallen off his chest. He was still wearing all his clothes. I could have walked right out the front door and slammed it and gotten away, but I guess I didn’t want to. I rubbed my lips, remembering his rough mouth.

His narrow galley kitchen was separated from the living room by a Formica bar. The fridge, pantry and stove all stood on the opposite wall in a line with the sink. A very squashy work triangle, but useable enough until you opened the fridge.

“What are you doing?” Phil sank onto one of the barstools.

“Good morning!” I said. “Wow. That’s backwards too.”

“What?”

“The morning. We shouldn’t be seeing each other with morning hair and the sleep stupids before we’ve had sex. We should be all after-glowed and satisfied before we have to look at each other in this condition.”

Phil scrubbed at his face. “Why is the refrigerator door in the hall?”

“It was backwards. I noticed it yesterday. The handle and hinges were on the wrong sides.”

“So you’re switching them? Before breakfast? God, before coffee?”

I surveyed Phil’s kitchen, then his face. They were both a bit of a wreck, honestly. Both probably my fault. “I don’t drink coffee,” I reminded him.

“But I do,” he said and stalked into his bedroom.

Fifteen minutes later he had showered and dressed, and I had reassembled his kitchen and done my best with his coffee pot. Five minutes after that, he suggested we go out for coffee.

“Ask a carpenter to dress you and you’ll wear wooden clothes,” I snapped, then tried to figure out what the hell I meant. Phil waited. I said, “You didn’t ask for any of this, did you?”

He shook his head and looked tired. “It’s okay,” he said. “I did know you do that—order your physical environment when you feel frightened.”

“I do that, or Celeste did?”

His rogue eyebrow twitched upward, but his voice stayed calm. “She did too, actually, but I wasn’t thinking about her.”

Nothing in his face moved. He sat impassively on the barstool, swiveling gently, looking out through the sliding glass doors into the yard.

“Bullshit,” I said.

He swiveled back to scan my face.

“No, not Celeste,” I said. “It’s all me.”

The eyebrow quirked a question mark my direction.

“You’ve been thinking about Celeste since we met,” I said. “She’s been a shadow under everything you’ve said. So either you’re so repressed you don’t know you have feelings at all, or you’re lying to me.”

“I have not lied to you.”

I mirrored his total lack of movement.

“But I haven’t told you everything,” he said.

I stayed quiet; it was working for me.

“Let’s go get some decent food,” he said. “I think we’d both be better for it.” He stood up and walked into his bedroom.

I got as far as the barstool side of the kitchen before I realized the bias-cut green dress and difficult stockings I was planning to put on belonged to a woman seventy years ago. I had darned the silk where it wore thin at the toes and could feel, on the backs of my knees, how they bagged before synthetics. I don’t wear nylons often. It’s too hot, and my legs are dark enough. But they’ve always been nylon. Celeste was mixing into me.

I faced Phil’s icebox. No, his fridge, hinged properly now. But the sharp edge of the counter bit into the palms of my hands, and my fingertips went cold with the effort of not trailing after him. I wanted him here to hold me, lock me down, grip my wavering reality in his big hands and bend it into sense.

Phil hit the light switch on the way out of his bedroom and started reeling the blinds over the glass patio doors. “Saves on the A/C,” he explained.

“I gotta go,” I said. “Make whoever do whatever and get me back to Phoenix. I need to stop and think this through.”

“It’s a little late for that.”

“What do you mean ’a little late’?”

“The memories are going to keep coming back, Ren. You can’t stop them. The best you can do is let me show you how to organize the lifetimes of personal information you’ll be getting. And how to graze the shared memory you have access to now. And how to put the two together and start your own meddlework.”

“Until I fade away altogether under Celeste?”

“Until it all settles out.”

There were no lines in the skin above his eyebrows, no sign of worry or concern, just information, but he came to stand where I was milking the Formica.

“You’re not an impulsive person,” he said. “You knew you could take your time to think this over. You wanted to experiment with it—watch me meddle, learn more about us.” A strange tenderness turned his voice liquid. “But you took the spike last night without waiting for any of that.” His words slipped over my shoulders like bath water. “You already had some meddlework in mind, didn’t you?”

I turned to look at him. “Did you know you can drown someone in two inches of water?”

The one wild eyebrow shot up, then dove. Surprised, then angry. “You’ve never drowned anyone.”

“No, I haven’t. But how do you know that? How could you know what I am? Can you even see me through all the Celeste hanging over me?”

“I’m not the only one looking.” There was no morning softness, no sluggishness left to his face. My bathtub iced over.

But I didn’t care. Whatever else he was going to tell me I was or wasn’t, I knew for plain fact I wasn’t needy. I wasn’t helpless or pathetic or wanting protection and a big strong man to save me. I might be in over my head, but I wasn’t wasting air shouting for the lifeguard. And I wasn’t giving up my secrets. “You told me you see patterns,” I said. “That your whole niceness mafia is based on changing people by knowing what triggers them and orchestrating those triggers, by manipulating them to be better, right?”

“To do better; being better sort of comes along naturally.”

“How?”

“I explained that, Ren. We each draw from lifetimes of wisdom and have access to a collective memory that houses almost every fact about anyone. We know how to make someone trust us, we know how to find a memory that will cause gratification. We manipulate and suggest.”

“Then nothing can surprise you? Ever?”

“You have.”

I leaned against the corridor wall. Phil dropped back onto a barstool, one wary eyebrow watching me.

“Then we’re even,” I said. “We should eat something.”

Phil nodded.

“I want the full Vegas experience, lavish buffet, dancing girls,” I said. “I want you to show it all to me, and I want my boss to pay for it.”

“With all of human history available to you if you close your eyes, you want to see Las Vegas?”

“Yup,” I said. “Didn’t see that coming either, did you?”

His wariness doubled in eyebrow. “Are you just trying to be unpredictable?”

“Would that be out of character for me?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“Then no, I’m not,” I said, like it was innocence and not exhaustion that kept me leaning against the wall. “But I’m not going to stay inside with the animatronics this time.”

Phil waited.

“For my seventh birthday, my parents took me to Disney World. Mom was pregnant; I didn’t know it yet, but I guess that was part of why we went: a last hurrah for the three of us, with the next two years going to be all diapers and learning to walk. The first morning, I had my first-ever room service meal and opened presents. I got a pair of plastic sparkle princess shoes from my nana’s sister, tore them out of their plastic bubble-pack, and wore them for breakfast in bed with my Tinkerbelle nightie and the room service tray. Do you know this story?”

He shook his head. “What happened?”

I pushed my back into the wall. “We got dressed for our big day at the park. Mom wanted me to put my Keds on, but I was the birthday princess, and either I convinced her that princesses do not wear sneakers, or she needed to throw up and just gave in. She packed the Keds in my new Belle backpack and sent Dad and me down to the lobby where I took them out and hid them in a potted tree.

“We took the monorail, stood in the entrance line, and half an hour into our day with only ‘Dumbo the Flying Elephant’ and ‘Main Street USA’ checked off my pages-long list, my feet started hurting. ’It’s a Small World’ and ‘Cinderella’s Golden Carousel’ later, I’d chewed a bloody place on the inside of my lip.”

Phil chuckled, warm and easy, and I liked the sound and the way his shoulders sat down away from his ears now without the tension that always rode them. “What did you do?” he asked.

“What could I? Fess up and wait with Mom while Dad went back to the hotel to root through the lobby plants? Accept his offer of a most un-princessly piggyback? Keep walking till my awful, plastic torture shoes left trails of blood through the Magic Kingdom?”

“No?”

“Never!”

“What then?”

“Develop a sudden and unnatural love for the ‘Hall of Presidents.’ No lines. All sitting.”

“Very clever,” Phil said.

I sat down on the stool next to him, but couldn’t quite meet his eyes. “I need help,” I said. “And I’m not willing to miss out on seven-eighths of the fun because I’m too proud to ask for it. But I’m scared and overwhelmed and have a lot to learn and I can’t learn it all right now. After the dreams I had all night, I need a change of scenery. I want to look away from all this and come back with clean eyes. I want to throw myself into an experience that isn’t mine, a movie or not-a-memory, something I can’t possibly be responsible for.”

“Let me show you Las Vegas,” he said. His eyes were the brown of bearskin.

“I’ll get my walking shoes,” I said.

Phil

Sinatra sang “Fly Me To The Moon” as the Fountains at the Bellagio went through their paces. I watched her, pleased she was enjoying it, and wondering how the hell I was going to get her to tell me what she had planned. It was wall-to-wall people, as always, but she didn’t seem to mind.

“I’m going to need a primer on the jargon,” she said.

“It’ll come back to you.”

“No, not Incrementalist jargon; poker jargon.”

“What brought that up?”

“You didn’t hear the conversation behind us?”

“I wasn’t paying attention, sorry.”

“I think I can quote it. ’I had the nuts on the flop. He called my push with fuck-all, and hit runner-runner straight.’”

I nodded.

“What does it mean?” she said.

“That he’s a whiner.”

“No, the terms.”

“The nuts is the best possible hand for a given board. A push means betting all of your chips. Fuck-all means—”

“I got that one. And I know what a straight is. What’s runner-runner?”

I did my best to explain, which required explaining the basics of hold ’em, which took most of the cab ride to Treasure Island. We watched the pirate fight, which had been better before it was just another skin show. A short walk brought us to the Venetian, where we wandered around the fake canals and got Italian ice and Godiva chocolate and admired the lighting job and, again, fought our way through the stifling, dense Las Vegas crowds.

After a cab ride to and from the Luxor we were at the Mirage, where I’d parked. We had the buffet, and I explained that the volcano didn’t start until night, and that we needed to wait for the Fremont Street Experience.

“There is,” she said, “a roller coaster.”

“Three of them, in fact, on the Strip.”

“Incredible.”

“If you consider America a large amusement park, Las Vegas is the Midway.”

“That is an interesting way to consider America.”

“It explains Las Vegas.”

She was done eating her samples of this and that; I finished my shrimp creole and stood up. “Want to gamble?” I said.

“No. What would you do if someone was about to shoot me?”

“What?” I stopped in midstride and stared at her. A middle-aged couple in matching Hawaiian shirts stepped around us. “No one is going to shoot you.”

“I know. But what would you do?”

“Convince the person not to. What are you getting at?”

“Convince the person how? Magic, or threats?”

“It’s not magic.”

“You know what I mean.”

“All right. Magic, I suppose, if I thought it might work. I’m not very intimidating. Why are you asking about this?”

“You study people pretty thoroughly, don’t you? If you’re planning to meddle with them, I mean.”

“Even more thoroughly if we’re trying to recruit them. What of it?”

We fought more crowds, and eventually made our way out into the Las Vegas heat that always hits like a tangible object, no matter how used to it you are. She ignored it, but she was from Phoenix, where it’s even hotter.

I handed the valet my ticket.

“Do you always do valet parking?”

“Habit,” I said. “Three buy-ins for a two-five no-limit game is about fifteen hundred dollars. If you’re walking around with that much cash in your pocket at two in the morning, a dark parking garage isn’t your favorite place to be. Now, you’ve been getting at something for the last hour. Ren, would you please have pity on me and tell me what it is?”

“Not yet,” she said.

“Are you enjoying this?”

“I’m not being coy. This is research. What did you and Celeste fight about?”

“God! What didn’t we fight about? Religion, politics, morality, food—”

“Ever since you’ve been Phil and she’s been Celeste?”

“She’s only been Celeste a few hundred years. But yes.”

“Meddlework. You were on opposite sides of a lot of them?”

“If it had been up to her, Antietam wouldn’t have been fought.”

“She thought it was too big.”

“If it had been up to Oskar, the entire Southern aristocracy would have been dispossessed after the war.”

The car arrived. I held the door open for her; I guess because she’d gotten my mindset into an earlier age. She accepted it without question, maybe for the same reason.

“The big fight with Celeste,” she said, like she was prompting me.

“The big one? This lifetime? The 2000 election. Florida. I still think she was wrong.”

“Then why didn’t you do something?”

“It was already done.”

“I mean, afterward. You could have exposed it.”

“It was pretty well exposed.”

“Not completely. Why didn’t you?”

“That would have been … I don’t know. Oskar wanted to. No one else did.”

“Why didn’t you?”

“Christ, Ren. It would have been huge. I don’t know. Because…”

I stopped talking and thought about it, trying to remember. I was in the Bellagio lounge when the election results were coming in. I was drinking Macallan 25. I was angry, disgusted. I picked up my cell phone to check flights to Florida. Celeste called right then, and said—

And said—

“Fuck. She meddled. With me. Long distance, for chrissakes.”

“I just thought you should know,” said Ren.

I turned onto the Strip from Spring Mountain, going through the red light. Of course, there was a cop there.

Fifteen minutes later, citation in hand, I pulled us out into traffic; extra careful the way you always are with those flashing lights right behind you.

“Will the car drive better if you pull the steering wheel off?”

I didn’t answer, but relaxed my grip.

“You’ve been wondering,” said Ren, “what piece of meddlework got me so excited I just went and jumped into this thing.

“Uh, sorry,” I said. “Yeah, but this thing with Celeste caught me off guard.”

“Right,” she said. “The thing I want; I think Celeste started it.”

Copyright © 2013 by Steven Brust and Skyler White

Order Your Copy