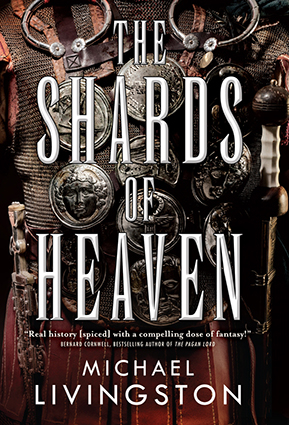

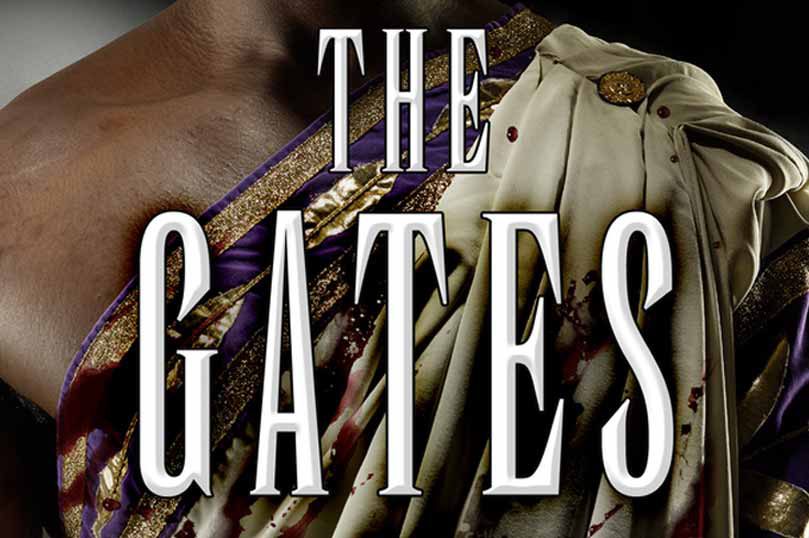

Presenting The Temples of the Ark, a brand new story from Michael Livingston, set in the world of his series, opens in a new windowThe Shards of Heaven. Michael’s latest novel, opens in a new windowThe Gates of Hell, will be available November 15th.

I do not know whether there are gods, but there ought to be.

Diogenes of Sinope

IT’S STILL DARK when I awake in the arms of the conqueror. The loose curls of his tawny hair have grown longer in Egypt, and they entangle with mine in a soft mat beneath my cheek, a few stray strands gently waving with my breath. The little oil lamp in the corner of the tent sets a faint glow against the shadows, and I smile at the truth of that feeble light. For all his rage upon the field, for all that he has walked the earth from Greece to Persia as a mighty king and killer of men, my strong-shouldered lover is afraid of the dark.

He stirs in his sleep, the corded muscles of his arm around me flexing and beginning to lift. I know the motion. I’ve felt it enough over the years. His mind and body at peace, he is turning away now, rolling to his side to face the outer wall of the tent. To look away from me.

That turned back bothered me when I was younger. I thought that perhaps it meant he was disappointed in me, ashamed of us.

Only later did I come to realize how it was his secret challenge to the world. In his sleep, in this weakest of times, he would expose his broad, naked back to the door, an invitation, a ready target to any who might wish the conqueror harm. And every night he wasn’t killed in his sleep would mean another night with the full trust of the men who’d sworn to follow him to the ends of the earth.

Which meant, of course, that he trusted me most of all.

I lift my weight off of him, giving him space as he sighs over to his side. His back shines in the dim light, and it casts the thick scar upon his shoulder into sharp relief. Only a few months since he took the spear-wound at Gazza and already it’s fully healed, as if it is years old.

One more sign of his divine birth, many think. One more proof.

None of them know, as I do, the truth. He’s as human as any other man. Divinity isn’t how the few blows that ever reach him heal with seemingly inhuman speed. Ichor doesn’t run through his veins, doesn’t explain why nothing can slow the onslaught when he dons his armor and the battle-rage boils over him, why he can press ever forward, scything men like dry wheat.

He doesn’t move as I slip free of the sheets and pull my simple linen tunic over my head. From a stool nearby I grab the wool cloak that’s traveled with me since I lost mine in Persia. Though the desert will be miserably hot in a few hours, it is cold before the dawn. I sit on the stool to bind my sandals, take one last look at the beautiful back of the sleeping king, and then I step quietly out of the tent and into a night filled with stars.

“Lord Hephaestion,” says the guard at the side of the flap, coming to attention.

For a few moments I can’t see him in the changed light, but I know the voice, just as I know the men assigned to keep Alexander safe. “Eustathios,” I say, acknowledging the big, reliable man who drew the duty this night.

“Couldn’t sleep, sir?”

“Not really. Don’t think I’ve slept well in Egypt yet.” I yawn, smiling as my body speaks its own truth. The clear desert air is indeed chilly, but the crispness of it feels good in my lungs, like cold water on sore limbs. It tastes of slowing fires.

“Me, neither,” Eustathios agrees. “It’s the sticking sand that does it. I’ve got Egypt between my toes. And by the gods it’s forever itching in my crotch.”

I grin as I shake my head mournfully, then stretch. I look up, tracing constellations in the great dome of sky. I did manage a few hours of rest, I can see. A good respite, but nothing like we need, nothing like what we’d get back home. “Can’t get out of this desert fast enough,” I say.

There’s silence for a few seconds. I’m still gazing at the wide stretch of stars, but I can feel him looking at me.

“You want to ask me something, Eustathios.”

He chews on his thought for a bit longer before answering. “Did the Oracle really say that he’s the son of God?”

The Oracle. The past few days since we left the oasis it’s been on everyone’s mind. Alexander and I have both known it. But what to say?

I shrug into the expanse. “Oracles never really say anything, Eustathios. It’s all riddles and maybes and whatever you want to make of it.”

“The men are saying it’s true, though. The Oracle confirmed it. And after Gazza, well . . .”

Gazza. The spear. That scar. It would have killed me — would have killed any other man — but Alexander had only switched hands on his blade and fought on, like a lion in the midst of the chaos. All the men had marveled at it.

Months before, counsellors had advised against the king leading such charges personally, but Alexander had always understood his men. They fought more bravely with him by their sides. And when they died — which so many did — they died more honorably.

“And what danger?” Alexander had once laughed. “No blow from a man can kill the son of a god.”

It had been a joke back then. We’d all laughed about it. By the stars, we’d grown up with Alexander. We’d seen him shit. He wasn’t a god, but he did have a god’s own luck. It was easy enough to joke that no mortal could kill him.

Now, after Gazza, after this Oracle, so many were like Eustathios, wondering if the joke had been truth after all.

I want to tell them all how preposterous it is. I want to tell them that I know the truth of who Alexander is, how he has become what he has become. No matter what some drugged desert hermit says, a man isn’t a god. Gazza didn’t change that. The Oracle didn’t change that.

But I know, too, the sacrifice that so many are willing to make for Alexander the man, how much he’s managed to achieve. What more could be done with Alexander the god? Could he conquer the world, bring peace after war?

“Alexander is of hearty stock,” I finally say to Eustathios. “You remember his father. Is that not enough to explain Gazza?”

“I saw the blow, Lord Hephaestion. I could not have survived it.”

“Nor could I.”

“So do you believe it?”

The stars, I keep thinking. They may put my friend there in the end. “Maybe the gods are what we make of ourselves,” I wonder aloud. “Maybe the question isn’t whether Alexander is a god, but whether the gods are men like Alexander.”

I look back to him, genuinely interested in the big man’s reply, but the sound of a horse pounding the earth turns us both away. Down the line of tents, we see the rider coming, his face flashing red as he passes the night fires.

“Hippolytos,” Eustathios whispers as the rider gets near enough to recognize. “One of the scouts.”

We walk forward from the tent to meet him, silently agreeing to move the noise of the horse and rider farther from the sleeping conqueror.

Hippolytos pulls up short in a rush of sand and dismounts with speed, saluting at almost the same moment he touches the sandy earth. “Lord Hephaestion,” he pants.

“Is it the Persians?” Eustathios speaks before I can, but it’s the very question that’s on my mind. The Persian governor of Egypt submitted to Alexander almost the moment that he crossed the border, but Masistes, one of the Persian generals, had raised a small force from the farther reaches of the Nile, and they were refusing to bow to Greek authority. Our scouts were sure Masistes was tracking us as we crossed into the desert, but we’d never managed to confirm the location or the size of his army.

The young man shakes his head as he catches his breath. “Nubians,” he says. “Tens of thousands strong.”

TALL ATOP HIS HORSE, Alexander shines in the brightness of the desert sun, his bronze breastplate glimmering in the waves of heat that shimmer up from the sands like phantom snakes. He smiles as I ride up from the right wing of our army. “All is well, Heph?”

I nod, reining into position beside him. We crossed into Egypt with 30,000 men. Some we left in the cities of the Nile, but far more were today working upon the edge of the sea, laying the foundations for a new city that would bear Alexander’s name. Looking out at the stretching expanse of exotic men that is arrayed against us — a sea of color and noise that undulates in its lines like pent-up waves ready to surge free — I find myself wishing we had those far away comrades with us again.

For a fifth time this morning, I count banners. I multiply them, and I know that even still we would be outnumbered.

But at least the odds might be improved.

“I don’t like the heat,” Alexander says in an off-hand voice, as if this is just another day, just another duty to be performed. “Though I must say I’ve never slept better.”

Eustathios, whose horse is just behind mine, chuckles, and several other men follow suit.

“I’m counting it four to one,” says one of the generals to Alexander’s other side. “Maybe five.”

It isn’t a tremor of fear, merely a statement of fact. We’ve fought at short odds before, and it has mattered little. The Thracians, the Syrians, the Persians . . . no matter their numbers, none had stood against the power of our Macedonian arms. So many had never seen anything like our core phalanx and our agile sweeps of cavalry.

Tactics, as Alexander once said, make up for many numbers.

But, it occurs to me, we’ve never seen anything like the Nubians before. What tactics would they have?

“They look like an army of lions,” another man says.

It’s true. Many of them wear leather armor over their dark-skin — little different, it appears, from what so many of our own men are wearing — but over this they have sashes of color, bands of fur. Here and there are men who seem to wear nearly whole skins of wild beasts. I wonder if they are officers.

“It is their leaders who matter,” Alexander muses. “I’d rather face an army of lions led by sheep than an army of sheep led by lions.”

The fact that he is wearing a golden helm in the form of a lion’s head — like Hercules wearing the skin of the Nemean Lion — goes unspoken. No man among us doubts that ours is an army of lions led by a lion who might well be a god.

I purposely keep from looking at that gleaming breastplate he also wears, though I’m presently aware of what it means for our enemies that he is wearing it. I’ve seen the rage it burns through him. I’ve seen the power and the possibility.

“Riders coming out,” Eustathios says.

Beyond the plain of sand between our armies, I see it, too: a small contingent has broken away from the Nubian lines. Four people are moving forward on resplendent camels, metal flashing golden from their flanks. They are moving at a slow pace, with four men surrounding them on foot, each holding aloft a long pole. A dark silken cloth is held taut between them, allowing the riders to remain in shaded comfort.

“Why don’t we have that?” Eustathios asks.

“You know why,” Alexander replies.

Eustathios stammers for a moment, clearly at a loss, and the conqueror looks to me with a smile.

“Because they couldn’t keep up,” I say.

Alexander lets out a light laugh. “Hephaestion,” he says, “my second self. Shall we?”

Without waiting for a reply, the king kicks his horse forward to meet the Nubian emissaries, and I’m left to follow, to chase him through the hot Egyptian sands.

I’VE KNOWN HIM since we were children. I’ve laughed with him. I’ve loved with him. I’ve fought with him and I’ve shed blood with him. And it occurs to me, as we come up to where the Nubian emissaries on camelback await us in their artificial shade, that I have never seen him so relaxed as he has been these past few days.

“One soul in two bodies,” Aristotle once said, chiding us for one of the many conjoined tricks we played upon our tutor. True enough in its way, I suppose. He and I are of one mind and one purpose. I am his right hand, acting his will without the awareness of his thought. I am, as he so often says, his second self.

But there is this difference between us: I hate this country.

In part it’s the damnable sand, of course. The winds raise it up like dust, push it in great billowing clouds that scratch like insects at our eyes, blinding us as they blot out the sun and erase our tracks. It’s a monstrous beast, this desert, and it wants to consume us.

Even when it’s not raised in storm, the sand simply clings to everything. It grinds in the teeth, grates in the sheets, and I simply cannot imagine how anyone can sleep at peace with it.

But more than that I feel an uneasiness in the air here. A tension in the foreign, hostile landscape. It is as if the whole of it is waiting, and I do not want to know what for.

Yet Alexander has welcomed it into his heart. He has founded what will be his greatest city here: his Alexandria, drawn up from the earth on the edge of the sea. And he has taken us a thousand miles across this desert to visit its Oracle, to learn that he is the son of god. He says he loves this land. And he wasn’t kidding when he said he hasn’t slept better. I should know.

His second self I may be, but I cannot understand these things. And I cannot help but wonder if this day is the day my foreboding comes to pass.

The four emissaries waiting for us could not be more different from what I might have expected at a distance. For one thing, only three of them are dark-skinned Nubians. The two of these at the center of the four, judging from their bejeweled and gilded regal clothes and high bearing, are surely the king and the queen of their country up the Nile. They are a young couple, but they do not seem troubled by inexperience or worry. Alexander and I have seen enough kings to know fear on sight, and this king and queen have nothing of it. They are as relaxed as Alexander himself, which is an accomplishment that immediately earns my respect.

A third rider, also Nubian, is on the left of the king. He wears fine cloth, and he holds a kind of scepter that I assume conveys rank of some kind, but he is clearly of much lesser status than the royalty in the party. An interpreter, I imagine. Or some kind of holy man.

As strange as they all are to my foreign eyes, the fourth rider is strange for his familiarity. A much older man, he has the paler skin of the people of the Levant. And he is wearing only the simplest of hooded desert robes. His nervousness only emphasizes how entirely out of place he is in the gathering.

Alexander and I stop our horses just outside the square of their shade. His steed shakes its mane against the heat, the metal of its harness shaking loudly in the stillness. He steadies it with a pat along its neck, then he reaches up to unclasp his golden lion helm, shaking out his hair. I follow suit, and we stare at the emissaries.

The Nubian king leans over to the woman and whispers something. She smiles in reply, her teeth a shocking white contrast to her dark skin. Then she nods.

The man nods, too, and the third Nubian speaks. “Do you speak Persian?” he asks.

Even before our defeat of Darius, both Alexander and I had tried to learn something of the language of those whom we intended to conquer and rule, but war had made our lessons scattered and ineffective. Some of our comrades, like Peucestas, had made remarkable headway, but we ourselves knew the language no better than children. Perhaps worse. “We know some,” I answer brokenly. “Do you speak Greek?”

“Better than your Persian apparently,” the king of Nubia says in rough Greek.

The interpreter looks from his king to the conqueror to me with wide eyes, clearly worried that there has been a breach in etiquette. But Alexander is smiling, and I shrug and smile, too. “So it seems indeed.”

“Ah … yes.” The interpreter stammers for a moment, but he begins to settle into a common Greek. He lifts his scepter in a gesture that clearly has import within their culture. “The qore of Kush, Nastasen, and the kandake, Sakhmakh, greet you, Alexander, conqueror of many.”

I watch as Alexander gives the king and queen the slightest of bows in turn. “I am Alexander of Macedon, king of Greece and king of all Asia,” he says, speaking relatively slowly so that the interpreter can translate his words into the Nubian tongue for the others. “I have taken this land of Egypt by arms and assent, and I have been rightfully declared by its Oracle to be its king. This is my land, and I will defend it.”

“Their majesties do not desire war,” the interpreter says after they reply in their tongue.

Alexander cracks his neck. “War there will be if you stay.”

The qore, Nastasen, laughs lightly, and he says something to his wife in Nubian that makes her smile, too, before he addresses the interpreter. “Numbers are on our side,” the man translates.

“And I am Alexander.”

“So you are,” Nastasen says in his own Greek.

For a full half-minute the two men simply stare at one another. The kandake — the queen — is staring at Alexander, too, but her eyes move more in a look of judgment, like a merchant appraising goods. It is . . . fascinating, I think, that she might think herself in a position to judge such a man as my friend.

Not wanting to stare at her myself, I find myself turning to look at the fourth man, the lighter skinned man. Alone among the many tens of thousands on the plain — alone except for me — he is not looking at Alexander. Not at the man, anyway. As I watch him I can see that he’s looking at the conqueror’s armor, at the gleaming bronze of the breastplate that Alexander alone is allowed to handle. And he is staring most especially, I realize with mounting horror, at the blacker-than-black stone that is locked into its center. He is staring at the thing that has made my friend a god, and he is smiling.

“As their majesties have said,” the interpreter is saying, “there is no desire for war here.”

“Your army speaks otherwise,” Alexander replies, casually leaning in his saddle to look past them at the great masses. The Nubian warriors are chanting and rocking in a frenetic anxiety. “And it seems to think otherwise.”

“The army will stay or go as the qore wishes,” the interpreter says. “He felt it was necessary for their protection.”

“From what?”

“From you, Alexander king.”

“I have no wish to conquer the land of Kush or the Nubian people. I came for Egypt. I will return to Persia from here.”

“It is not your armies we fear.”

“Then what?”

This time it is not one of the Nubians who replies. It is the fourth man, who has at last stopped staring at Alexander’s armor. “Your rage, god among men.”

Alexander turns to him, his eyes narrowing. “My what?”

“Your rage,” the man repeats, and he nods toward the breastplate. “It sits on you even now as a flame ready to alight.”

No one but myself knows the secret of what we found in the sanctuary of Athena at Delphi. No one else could be trusted. So when Alexander turns his eyes in my direction, I have nothing to give him but my own wide-eyed bewilderment.

“We know something of what you carry,” Sakhmakh says through the interpreter.

“What do you think you know?”

“We know little,” she continues. “But our friend here knows much. And he has told us enough to understand.”

“What do you want?” I ask.

Nastasen nods at me, a subtle gesture of respect. “What we want, Lord Hephaestion, is a favor from the great king, Alexander.”

“A favor?” Alexander asks.

“We want to give you a gift,” Sakhmakh says. “A gift that must never be used. A treasure that must always be protected, that perhaps only you can protect.”

Alexander and I exchange another glance, and then I spread my arm across the sand before us.

“No,” Sakhmakh continues. “We cannot give it to you here. We dared not bring it. But we will take you to it.”

“Take us?” Alexander asks.

“Just you,” the kandake says. “And your companion, if you will. In good faith only myself and Terach will accompany you. Our armies will withdraw by other ways.”

The pale-skinned man smiles, and I assume he must be Terach. “Where?” I ask.

“Not far from here is the Way of Forty Days,” Sakhmakh replies. “It is a path long-traveled between our country and the sea. It will speed our journey south, across the sands to the southern oasis. There is good water there, and good shade. From there you can travel north on the Way, or you can travel take a boat down the great river — however you wish. You can meet your army in Thebes, if that is your destination.”

I almost want to laugh, but I can see the serious look on Alexander’s face. He’s considering it.

“You wish for us to go with you,” I say, “among your people, surrounded by your thousands, back toward the heart of Kush? More of your army could be waiting for us.”

The Nubians listen and nod as the interpreter translates the words. “Our thousands,” Nastasen finally says, talking not to me but to the conqueror. “And you are Alexander. If we are right, if you have what we believe you have, do you think such numbers really matter?”

“The Aegis of Zeus protected Troy from all Greece,” Terach abruptly says, and he is once more looking at my friend’s breastplate. “I’m certain it will protect you from us, great son of Macedon.”

WE LEAVE THE NEXT DAY, after preparations are made for the journey, including the organization and direction of the army in our absence. Many of the men were shocked when Alexander announced that he and I would leave the army for a time and rejoin them in Thebes. More than a few, especially wary men like Eustathios, voiced concern for the king’s safety. But in the end none could stand up to Alexander’s fiery gaze.

As our final preparations were coming together, I learned that there was a rumor in the camp that he and I were journeying to yet another oracle. It had only been a matter of days since Alexander had walked alone into the presence of the Oracle at Siwa, and then, they said, he’d been declared a child of the gods. What more, the men whispered, would this new oracle bring?

I said nothing when I was asked about these rumors. I know too much.

As promised, only four of us have ridden into the desert together: myself and Alexander, the kandake of Kush, and Terach, who is, we have learned, from Jerusalem. We left an hour before dawn. No fanfare. Just a steady ride between the packing armies, headed west for the Way of Forty Days. Finding it, we turn south for the deeper desert.

Sakhmakh is unlike any queen I’ve ever met, and I can tell that Alexander feels likewise. She wears white linens, trimmed with gold, that drape over her shoulder and breast, bound about her waist with a beaded and jeweled sash. The gown is cut so loose that it moves in waves about her as she rides, and more than once I have found myself avoiding the hints it makes about the body beneath. Her skin, like her husband’s, is the color of rich cinnamon. It is dark against the brightness of the sands, yet in the light of the sun it seems to radiate an inner warmth. Without doubt she is beautiful in her way, but I have found that most queens are. No, it isn’t her beauty, exotic though it is, that makes her different.

She catches my eye — and Alexander’s too, no doubt — because of how free she seems. She sits as straight-backed as any Persian princess we have known, her head held high on her dark and slender neck, but there is an honest readiness to her smile, and an unbidden laughter in her dark eyes, that reminds me of someone entirely unbound by regal customs. She rides with a shocking comfort, seemingly as comfortable on her gilded camel as some of our Greek countrymen are on their steeds, I would dare to say. And perhaps strangest of all, she shows not the slightest concern for being alone in the desert with three men, one of whom is the conqueror of all Asia.

Sometimes, when I catch her looking at me and smiling, I wonder if she knows.

She also enjoys talking far more than I would have expected. Her Greek, we quickly learn, is far better than we had been led to believe in our initial meeting. She asks many questions about our travels, confirming and reconfirming the truth behind the stories that are told of the great Alexander. She is relentless in her pursuit of knowledge, I think, and Alexander seems glad to tell her all that she wishes to know. Her eyes are full of wonder when they talk, but it is not worship. I think he is glad for the difference.

Ahead of me, the kandake and Alexander are riding side by side on the Way of Forty Days. He is telling her of the siege of Tyre. The city was undefeatable, it had been said, because it was built upon an island, encircled by the sea. Siege engines could not be brought to bear upon its walls. My friend is smiling, telling her that he nevertheless broke them.

“How?” Sakhmakh asks. “Would you not need the engines?”

“Of course.”

“But you said the city was surrounded by water?”

“It was, yes. My men built a causeway to the city. It is no longer an island.”

I see her swallow hard, her eyes wide. Yes, I think, sending her my thoughts. Alexander bends even the earth to his will.

The Jew, Terach, has ridden toward a ridgeline of sand and rock ahead of us, and he calls out to the kandake to join him. She takes her leave of Alexander with a short bow, and then she drives her camel forward in the heated dust. As she leaves, Alexander pulls up rein until we can ride beside each other, he and I. Despite the heat, he is still wearing his bronze armor. He enjoys the company of the kandake, but not enough to trust her completely. He smiles over at me, and I realize it is the first time we’ve been alone since the coming of the Nubian army.

“Why are we going with them?” I ask.

“I think you know why, Heph. Because I need to know.”

“To know what it is they are offering?”

Alexander shrugs, a toss of his hair in the sun. “Or what it isn’t.”

I sigh. “You’ve more gold than Midas, more jewels than any man can dream of. What use is more treasure?”

He frowns for a moment, before a lightness strikes upon his face. “Do you remember when we were young and went to Corinth?” He smiles at his own memory. “Do you remember when we met Diogenes?

I lean back, smiling, too. “Of course I do. How could I forget? One of the most famous philosophers, living in his clay pot, as they used to call that little hovel. Aristotle warned us not to bother with Diogenes, but of course we took that as a challenge.”

Alexander laughs lightly. “So we did.”

“And there he was,” I say. “I remember you walked up and told him that you were the son of Philip of Macedon, the student of Aristotle, and that one day you would conquer all of Greece. You asked him if there was anything he would ask of you. Gods, I remember it as if it was yesterday morning. He blinked up at you, studying you, and then –“

Alexander’s voice cracks with feigned age. “‘Stand a little out of my sun.'”

I laugh, just as I laughed then. And I know that at some level, for all that has come upon us, he and I remain those two young men standing before old Diogenes.

Alexander laughs, too, but not for long. “When I say we’re going with them because I need to know, I guess it’s really because Diogenes was right. He saw the truth of me. He saw the truth of all of us. Glory fades, Heph. Life fades. We’re all mortal.”

I give him a sidelong look. “Maybe not all of us.”

Alexander the Great rolls his eyes. “Yes. Me, too, my friend. Whatever else this armor is, whatever else it does, it is no shield against time. Death will find me one way or another. Even Achilles had his heel.”

“Still doesn’t explain why we’re riding into the desert … riding, for all we know, into the waiting trap of an army. The Aegis of Zeus — if that’s what it is — may protect you, but it won’t protect me.”

Alexander reaches over to squeeze my shoulder. The grip is strong, and it lingers. “It is no trap. It’s a chance to know more, to understand more. About this armor, for certain, but also about us. About them.”

Ahead, Sakhmakh and Terach are conferring. The kandake looks from us to something below her on the ridge. She is smiling and laughing in the sun, and I can feel Alexander’s envy of her freedom.

“She is fascinating,” I say. “Did you see how easily she moved among her people as we prepared to depart? Like she was one of them.”

“A good leader must be,” Alexander says. He’s gazing at her, too.

I nod. It was the reason he fought in the lines, the reason for the Gazza spear that would have killed him if not for the power of the armor he wore. I think back to the conversation with Eustathios, and how the men thought of Alexander more and more as a god. “But surely a leader must be feared to be most obeyed,” I say.

“Obedience isn’t everything,” my friend replies. “I assure you I would far rather excel others in the knowledge of what is excellent than in the extent of my power and dominion.”

Sakhmakh is waving us up, but I feel Alexander’s eyes upon me. When I turn toward him I see that he is looking at me with a smile of genuine affection. I see, too, the wrinkles at his eyes, creases in flesh once smooth.

“So Diogenes was right?”

“I think he was,” Alexander says, “though there’s time enough to live still, you and I.”

“Life with a god-man has been good so far,” I say, “though I’d rather like to get out of Egypt, if you please.”

He laughs a little, then straightens himself on his saddle as he looks back toward the kandake and motions that we are coming. “Soon enough. And you know, Heph, perhaps I won’t always be Alexander,” he muses.

“If not Alexander, then who?”

“Well,” he says, “truly, I tell you, if I were not Alexander, I would be Diogenes.”

My friend rides forward through the sand and sun. And I, as I always will, follow him.

THE TEMPLE OF THE ARK is a white block of stone rising from the lush greenery of palm and date trees that surrounds us. It has taken more than a day to reach this quiet place, but the sliver of green that Sakhmakh had pointed out from the ridge line, the tiniest hint of living color waving in the sandy heat, has resolved itself into a magnificent oasis in the middle of the desert. Occasional tents dot around the pools that we pass, or cling to the spots of cool shade beneath the larger trees. The people we see smile and wave. Some look Egyptian, others Nubian, and others might well be Persian. None seem concerned at our appearance. None seem at odds. It is as if the hostilities of the outside world have no place in this refuge in the desert.

As we have been approaching this place, the kandake has told us a story whose strangeness can only be matched by the strangeness of our company — a king, a queen, a Jew, and me — making our way beneath the sun. She tells us that two hundred years earlier a group of Jews had come to the lands of Kush, seeking asylum. They had with them a most powerful weapon: a box that contained a stone said to hold the power of their God. The qore and the kandake welcomed them, granted them sanctuary, and gave them the peace to continue their worship as they saw fit. The only price was that the Jews would promise to use the weapon to defend them if ever they were attacked. It had been this way for two centuries, Sakhmakh says. But the time had come for the Ark, as the Jews called it, to find a safer home. So they had moved it to this desert oasis, this new temple for the Ark, and here they hoped to give it to Alexander.

Alexander and I have listened quietly, and I can see he is forming the same questions in his mind that I am. We had the same teacher, after all.

“Why now?” he asks. “Why me?”

Sakhmakh smiles. “Because the one who leads the Jews asks that it be so.”

Alexander nods, and he turns to address Terach, the Jew who has ridden in silence beside the kandake as she has spoken. “You are descended from those who brought this Ark to Kush?”

For a moment Terach looks back and forth between the queen and the conqueror, seemingly confused. In reply she simply smiles and makes a gesture to him as if giving him leave to speak. He sighs. “I am,” he says. “Though I’m not the only one. From Jerusalem to Elephantine in the time of Manasseh, from Elephantine to Kush in the time of Nebuchadnezzar, from that time to this, my family has kept the Ark safe.” He reaches into his robes and pulls forth a thin chain that is clasped around his neck. Hanging from it is the symbol of a circle inscribed upon an inverted pyramid. “This is the mark held by those who protect the Ark. It is carried by all who watch over it.”

I don’t recognize the symbol, and I doubt my friend does, either. “This doesn’t answer Alexander’s question,” I say. “If it has been safe for so long, why move it?”

“It has been kept safe,” Terach says, “but often so at the cost of lives. It was only with God’s grace that we brought the Ark out of Jerusalem, and it was a further miracle still that it escaped Nebuchadnezzar’s reach.”

We are passing a small pool just outside the temple grounds, and the Jew nods over to a young Egyptian woman washing clothes in its waters. She smiles in return. As Terach turns back to us, he seems to shrug. “And Kush has been safe, it is true, but not without peril. The kingdom will surely not stand forever.”

I blink, and I see Alexander’s back stiffen in his own shock. The kandake, however, seems strangely unaffected. She is looking ahead at the square stone arch that marks the entrance to the walled temple complex we are approaching. Beyond the archway is a paved avenue, and I can see a line of sphinxes guarding its length, all the way up to the columned portico and the tall square shape of the temple itself, rising clearly above the white stone walls of the complex. There is a vague smile on her face, and I wonder if she even heard Terach so casually predict the end of her throne.

“Is there a threat?” Alexander manages to ask.

“Just one,” Terach says. He, too, is looking up toward the temple of the Ark now. A man has appeared there. He holds up a brown hand to shield his eyes as we approach. He is unarmed.

“Who?” Alexander asks.

Sakhmakh pulls her camel up beside the entrance, and the man on the ground reaches out to hold its reins. She says something to him in a language we cannot understand, and he nods deeply as he begins to gather the rest of our reins, too. The kandake stretches and then swings her leg to slip down to the ground. As she settles her feet onto the earth, she looks up at my king. “You, Alexander. Only you. Come. It awaits.”

We pass beneath the archway on foot, Terach and Sakhmakh in the lead. As we walk along the swept stones, I see that there are other people in the temple complex coming and going. Many are in hooded robes not unlike that worn by Terach. I cannot see their faces. A few seem to be pilgrims of one sort or another, standing before the little shrines that are scattered inside the walled grounds.

At first I think that no one has noticed us, but as we close in on the temple I become aware that many of the hoods are turning to follow our passing. And glancing furtively to either side, I see that there are at least two men on either side of us, carefully pacing our advance.

As we pass through the off-and-on shadows of the columned portico, I let my hand casually brush the grip of the blade at my hip, reassuring myself that it’s there. “Alexander,” I whisper.

“I see them, Heph.”

He is wearing his armor, I remind myself. Come what may, he has the Aegis.

The doors of the temple are open, and Sakhmakh and Terach disappear into the darkness. Alexander and I step into the shadows behind them.

There are oil lamps burning atop bronze tripods just inside the doorway, but their flickering flames are feeble compared to the glare of the sun and stone outside. Only when the doors shut behind us do my eyes truly begin to adjust. I see that the inside walls of the temple are engraved with images of myth and legend, the shapes and symbols of gods and men etched into the surface of the stone. Layers of paint bring the figures into sharp vitality. The air is heavy with years of incense.

We are also, I see, no longer alone. Terach and Sakhmakh have been joined by two more hooded figures. They are talking quietly before one of several doorways that lead further into the building.

It is Terach who finally pulls away from them to turn to us. He bows to Alexander. “I hope you will forgive us,” he says, “but you cannot pass further wearing the Aegis of Zeus.”

Alexander’s shoulders, I see, tense up. I can see a tightness in his jaw, too, though he is quick to relax it. Even in the little light of the lamps the polished armor shines beautifully. All except the stone. It sits like a pit in the center of his chest. “You believe that is what this is?”

“I believe others believe it to be so,” Terach says. “As for what it is, what it truly is, that is a much longer tale indeed. What is important now is that it is of a kind with the Ark, though their powers are different. What the Aegis does for your life, the Ark does for the earth.”

Alexander half-cocks his head. “You fear me possessing both?”

Terach chews on this a moment. “I would say to the contrary, Alexander, we expect you to possess both. That is why you are here. But we want you to understand what they are. And we want you … unstressed, conqueror of kingdoms.”

“The rage.”

Terach nods. “Just so. It would be best to have a most level head in these matters. I assure you we mean you no harm at all.”

“Alexander,” I whisper.

My friend doesn’t look in my direction. He simply holds up his hand to end my speech. My mouth freezes, partly agape. “Very well,” he says to the Jew. “Heph, can you help me?”

He turns his back to me, and for a moment I’m back in that tent, our sweat upon me, watching his back turn toward sleep. The ultimate trust. I reach forward and begin to unbuckle the breastplate.

“I need to know,” he whispers to me. “It’ll be alright.”

I nod, for there is nothing I can say. As the last buckle is undone and Alexander pulls himself free of the armor, he lets out a long breath, a tired sigh. It is not the weight of the plate, I know. It is the power. It feeds on him somehow, even as it keeps him alive. We do not understand this, and I’ve no doubt that it is the answers to this that Alexander seeks more than anything else.

Terach watches my friend disencumber himself of the Aegis. When Alexander notices his observation, he smiles. “You know, you didn’t answer the rest of my question.”

“What is that?”

Alexander slips his forearm through the shoulders of the armor, holding it up. “Why me?”

“That’s best asked of the one who leads us.”

“That’s not you?”

“Hardly so,” Terach says. He turns toward Sakhmakh, who has at last finished her conversation with the other figures and has walked up to join us. “It’s her.”

Alexander stares, but I find the words for us both. “You’re in charge,” I say.

“I am.”

“But you’re the kandake of Kush,” I say.

When she smiles in return, a part of me feels as if I am a child. “A woman can do many things,” she says.

“You don’t look like a Jew.”

“But like my mother before me, I believe as one, little though it is known among our people.” She turns toward Alexander. “Are you also surprised that a woman could be in command of such a company? This does not seem the way of things among your people.”

Alexander’s smile is fast and genuine. “Oh, you’ve never met my mother.”

“Quite a woman, I imagine.”

“You’ve no idea,” I say, interrupting.

Sakhmakh raises an eyebrow, her eyes flashing with what appears to be mischief. “Very well,” she says. “Terach, carry the Aegis. Keep it close, but do not touch its stone. Now come, son of a great woman. It’s time for you to see the Ark.”

THE ARK OF THE COVENANT, as the Jews call it, sits in a small side room within the temple. The surrounding structure, we are told, is largely a Persian construction, built to honor the three gods of Thebes. I even recognize the figure of Darius carved into one of the walls just outside the doorway to the chamber housing the Ark. The Persian king is depicted holding forth an offering bowl to the gods, with the tall crown of the pharaohs upon his head.

That crown, I muse to myself, is no longer his. It belongs to my friend, who walks beside me into the chamber holding the Ark and, like me, stops to simply stare at it.

The Ark sits at the end of the chamber, its broad side facing us. It is wrought of a polished wood whose grains gleam in the torch light. Acacia, if I make my guess. The base is wider than the top, and long poles are mounted into metal rings at its sides, to ease its transportation. Thin filaments of metal weave around and about its surfaces like vines, and facing us directly, I can see, is the same symbol that Terach wore around his neck: an inverted pyramid within a circle, with a line cutting through its bottom third. All that would be remarkable enough, but far more striking is its gold-trimmed top, which is adorned with the statues of two winged beings who appear to be knelt in prayer toward one another: one fashioned of silver, the other of gold. Their wings sweep forward before them, the feathered tips almost appearing to touch each other. Beneath that, between them, I can catch a hint of deepest black, something flush with the surface of the top of the Ark.

“By the gods,” Alexander whispers.

“By the one God,” Terach corrects, and his voice is striking for its seriousness.

“Whether you believe in the God of the Jews or not doesn’t matter,” Sakhmakh says. She is in front of us, staring at the Ark with her own obvious sense of wonder. She takes a deep breath and at last turns to face us. “But you must believe in this: the Ark contains a part of the power of God, far more powerful than even the Aegis. Because it is a part of God, it is a part of creation. But it does not belong here. It must not be used.”

Alexander takes a step toward the Ark, then stops. I see him chew on the inside of his cheek, a habit I’ve long since given up trying to relieve. “Part of a god’s power. Even greater than my armor. I could do so much with it.”

I feel movement in the room, and I turn to see that there are four hooded figures behind us. They are close to my king’s back. I do not doubt that they are armed.

“You could,” the kandake admits. “That is the danger no matter who possesses the Ark. It is a danger even for anyone who is in reach of such power.”

Alexander still stares at the Ark. “So what is the answer to my question, Kandake Sakhmakh, keeper of the Ark?” Alexander at last turns to face her. “Why me?”

“Because you know enough not to use it,” she says.

His eyes narrow. “Because of the Aegis.”

Sakhmakh gives the slightest of nods, an acknowledgement of respect between sovereigns. “You’ve controlled it, but we both know it has been difficult. And the Ark is far greater. You know only too well that it would destroy you. As it would me.”

Alexander swallows hard. He does not like to admit weakness, my friend. But he knows the truth as well as I. “Agreed.”

“And you can protect it in ways we cannot,” Terach says.

Alexander turns to the voice, but he quickly shifts his focus back to the queen. “I cannot carry it with me,” he says to her. “I’m on a campaign, my lady. My army marches deeper into Persia, to find Darius and hunt him down like the wild dog that he is.”

Sakhmakh blinks, and I imagine she is surprised by this sudden turn toward bloodlust. But she shouldn’t be. Alexander is a conqueror. “No, I would not have you march west with it,” she frankly says.

“What then? How can I protect it?”

“By giving it a new home,” Terach says. “In a new city. A temple that is a tomb, buried beneath the ground, unknown to all but a chosen few.”

“A new city?” There is confusion on Alexander’s face.

I’m not confused, for I can see the perfection of what they hope to achieve, the fortuitousness of our timing. “Alexandria,” I say, turning the room’s attention in my direction. “They want you to hide the Ark in Alexandria.”

Sakhmakh smiles gratefully. “That is precisely what we wish to happen: for the Ark to be made safe and secure.”

Alexander nods, his eyes narrowing in thought as he turns back toward the Ark before us. I watch as the flickering of the lamp flame shifts the shadows of feathers on the winged creatures. It makes them seem to ripple with life, an expectation of movement, as if those kneeling figures are prepared to burst up from their knees, stretching themselves up and out as they let their strong wings beat a steady rise into the heavens.

“Very well,” Alexander finally says. His voice is quiet, almost reverent. “We will take it to Alexandria. We will build it a new temple there.”

THE ATTACK COMES just as the hooded figures — all of them, like Sakhmakh and Terach, members of the secret group of Jews sworn to protect their sacred treasure — have maneuvered the Ark out of the temple and into the shelter of the columned portico outside to await the cart that has been summoned. The brightness of midday has become the dusky shadows of evening, the sky a deep red as the sun sets far beyond the sands behind us.

There are shouts beyond the walls of the complex, a rushing of many feet, and the ring of steel.

Alexander and I are standing close beside each other to one side of the entrance, and we have fought in close quarters before. There is no thought, only instinct. In an instant our swords are drawn, our backs meeting. “Treachery,” I say, spitting the word at Sakhmakh. Standing at the other side of the entrance, the Ark between us, I see Terach, still holding the Aegis. His eyes are wide in shock.

The kandake of Kush stands in the doorway of the temple, backlit by the steady fires within. She shakes her head even as she begins to give commands in a language we don’t know. The hooded figures lower the Ark to the ground quickly but carefully, then they fan out in a rush, ducking behind stone pillars, retreating back into the temple, or running off into the night. Many of them, I see, are drawing swords from beneath their cloaks. And those who’ve hurried into the temple are back almost at once, carrying bows and sheaves of black arrows.

With a sinuous grace, Sakhmakh slides forward to stand in front of the Ark. She has in her hands two long daggers, their twin blades — each as long as her forearm — thin and sharpened to a wicked point. Where she hid them under her clothes, I do not know, but she holds them like an extension of herself. She rises up before us, before the Ark, swaying ever so slightly between the balls of her feet, like a cobra ready to strike.

Alexander and I exchange glances. If the Jews are not attacking us, then who?

A high whistle pierces the night. Then another and another. One again our instincts take over, and Alexander and I tuck ourselves behind a stone pillar just beside the entrance. Around us, it seems everyone else has done the same.

All but Sakhmakh. She does not move from the front of the Ark. It is as if she intends to protect it with her royal body.

We can only see the vaguest streaks of the arrows sailing in the dim air, but we see them clearly enough as they land, clattering off the pillars around us with a noise like hail.

When the volley stops for a moment, I take the chance to stoop down and retrieve one of the spent arrows from where it has come to rest by my feet.

“Greek?” Sakhmakh asks over her shoulder. She still hasn’t moved. It’s a miracle, I think, that none of the missiles has struck her.

Turning the arrow over in my fingers, I know at a glance that it isn’t Greek. And I doubt it is Nubian, either. I’ve seen its like more times than I can count. “Persian,” I say, holding it out to my friend

Alexander takes it, nods, then tosses it into the shadows. “Masistes,” he says.

At a shout from Sakhmakh, I hear the sound of defenders launching their own volleys in return. The whistles move away this time, but there are far fewer of them. “Persians?” she asks us in Greek.

“How many I don’t know,” Alexander says. “They were in the desert. Don’t know how they found us here.”

“Spies,” the kandake says before she barks more orders to her men. “You are a recognizable man, Alexander.”

Whistles sound another volley of arrows, and once more we tuck into the shelter of the tall columns. Screams echo over the courtyard before us. Arrows finding their marks.

When the wave is over, I am beginning to stand up and step around the pillar, to try to survey the situation we face, when Alexander is suddenly shouting from behind me. “Right flank, Heph! Down!”

My king throws himself into my back, and we tumble forward onto the stone pavement. I feel the screeching wind as the flanking volley of arrows that were meant to tear into us rip through space instead.

“Terach!”

At Sakhmakh’s shout, I push myself up from my stomach just far enough to see that the old man has fallen. He is gasping around the arrow that sticks out from his shoulder like a terrible barb. He is kicking himself across the ground in the panicked shock of a wounded animal. The Aegis has fallen from his hands, not three strides from us.

“Alexander,” I call out. “The armor!”

Even as I say it, I know it’s too late. Beyond the Aegis, beyond Terach’s kicking legs, I see the Persians coming. It is only a small squad of them — likely all they could get over the walls, with the primary force preparing to charge now through the main gate — but it may well be enough to destroy us. I see four or five hooded figures shifting their defense to protect our flank here, but there’s a dozen or more Persians coming at a full sprint. The setting sun casts a red light like fresh blood upon their swords.

“To me, Heph!” Alexander is rolling to his feet, and I kick myself up onto my own.

Together, like the young and foolish warriors we once were, we run forward past the Ark, leaping Terach and leaving behind us the Aegis, and we meet them with a roar like mighty lions.

SLOWLY RETREATING over ground covered by the slain, out of the corner of my eye I see the second wave of Persians coming through the archway of the main gate, pouring into the temple complex like a screaming liquid of blood-thirsty men. I see them, and I know we are lost.

I trip over something, stumble, and I recognize that it is Alexander’s armor, littered upon the pavement with the blood and the detritus of battle. The Aegis of Zeus, which brought him life at Gazza, which turned aside the arrows at Issus, sits now unused and useless. It cannot help us now.

One of the Persians has pressed his advantage as I stumbled, and I only barely manage to get the blade in my right hand up in time to stop the blow. The ring of the metal rattles my bones, grinds my teeth. I taste blood in my mouth, and I don’t know whether I’ve bit open my tongue or my cheek or both.

I’m halfway to kneeling, and I push myself up against my enemy’s weight, reaching out with my left hand as I do so, catching the wrist of his sword-bearing hand. It exposes me, I know. If the man has a blade in his other hand, he will open up my gut. But he does not. Or he forgets that he does. And I’m able to push his sword off mine and, still holding his sword hand up, reach back my own and plunge it through the sweat of his arm pit and into his body.

He sprays gore as I kick him backward, and he falls to the ground to writhe out his end. One more obstacle for the remaining Persians, a few more precious seconds for me to postpone the end.

Alexander pulls back from his own latest victim, rolling around behind me to run to the side of Sakhmakh. There are many corpses in front of the Ark there — a few of her fellow Jews, far more of the Persians — and the knives of the kandake are dripping in the light that streams from the temple doorway. Ahead, surely a hundred Persians are bearing down upon them.

Alexander and Sakhmakh give the slightest nod to each other. They smile, and then they turn toward the onslaught, two against them all.

Like Leonidas at the Hot Gates, I think.

Another Persian comes forward, but he is tired, and I dispatch him quickly. Only a few are left on my side, and I wonder about abandoning it to go stand beside my lover, friend, and king. If I would die, it would be by his side.

I back toward them slowly, keeping a wary eye on the remaining Persians. There are streaks and pools of blood where wounded men have tried to drag themselves away from death. I step carefully through it, sword between me and the enemy. They continue to hold back, seemingly content to let the coming horde finish me off with the king who once defeated them.

My heel strikes wood. It thumps like a hollow drum, deep and resonant.

The Ark.

I imagine its top surface, and in my mind’s eye I can see that between the two winged figures — the two angels still gleaming silver and gold, still freshly shined despite the horror of the gore that has splattered the pillars and the ground all around them — is the circle of a stone, blacker than black. I know in an instant how it will work. Alexander has often enough described how he uses the Aegis.

I look to the men before me, then I glance over to the screaming masses who will kill the kandake and my Alexander.

Without another thought, without hesitation, I throw down my sword, turn, and place both of my hands down upon the top of the Ark. I place them upon the stone.

The surge of power that erupts against my skin is so instant, so powerful, that I have to close my eyes and cry out. The power is hotter than fire. Inch by inch it envelops me, consumes me, as if I am leaning deeper and deeper into stone made molten in the forges of Hephaestus, my namesake god. Whether the world yawns up to me or I cave down upon it, I cannot tell. I’m uncoupled from the earth.

And then abruptly the heat turns to cold, into a deep void of swirling darkness that looms up and beckons me down. I feel myself falling, sliding, tumbling into the pitch night, and in my mind I scream down toward the hurtling abyss, though whether my throat has air enough to make a sound I don’t know.

Heartbeats have passed. Seconds. But if feels like years are being stripped away. I try to pull away, to swim up against the pull of the bottomless pit that wants to draw me on and on into oblivion.

Something jolts me as I fight against that rushing force, and somewhere in the distance I feel the bones of my arms threatening to snap, like twigs in the grasp of an angry beast. But the pain washes away. Everything is washing away. My body. The temple. The damnable sand. And Alexander.

Alexander!

The memory of him rolls over into my mind, like the form of him rolling over in our bed. The trust. The love. All stripped away. All passing into void, into nothing, into the darkness of death and eternal quiet.

No.

It’s a whisper in my mind, but it thrums louder.

No!

I fix my mind upon him. The memory. The imagination.

No!

The world stops. The swirling and sliding abruptly ends, and the power that has been surging over me is suddenly, I realize, surging within me.

I open my eyes. Alexander and Sakhmakh are there, dancing with death. The first wave of the Persians are upon them, and in a frozen instant I see the hatred and the rage upon those foreign faces. I see my king’s impending death. Only seconds remain.

Closer, I see how my fingers are curled and tensed, as if my fingertips intend to open wounds in the terrible, beautiful black stone. There is blood slashed across the darkness there, like red grooves, but the pain is something I cannot feel.

Unlike the fear. No, the fear is something I feel very deeply.

That, and the power.

So as I watch the wall of Persians coming, as I watch the wave breaking over and upon those two figures framed by the frozen spray of blood and spit and sand that hangs in the strangely calm light, I know what to do.

What the Aegis does for life, the Ark does for the earth.

The rock. The stone. I can feel the elements all around me. Under my feet. In the columns. Waiting. Ready.

I let the power of the Ark beneath me draw up through my palms and those flexed fingers. I let it wick up into my flesh, higher and higher, and then I reach out to the paving stones that mark the path between the long line of sphinxes. The feet of the mass of men that have been falling upon them are, for the moment, stilled.

The power has come into me like oil rising into cloth, and with the spark of a thought it ignites within me.

A moment later, the power explodes forth from me. Time returns. Feet fall once again. But the surge I have released is a roar, and behind it comes the scream of the earth.

Like a wave passing beneath their surface, my power lifts the wide paving stones. As it rolls forward the attackers are toppled and throne, scattered like cut stalks of wheat.

Then another thought, another spark of flame in my mind, in my soul. My hands scrape stone in a tortured agony I can sense but not feel as the fire of power burns and pours forth. In response, down the length of the shattered stone road, the sphinxes that line it rise up. With a thunderous crack of rock, they shake off the chains of their makers and hungrily look down upon their prey. As one, they slouch forward in birth and mindless destruction.

In my mind I see the carnage, but I don’t know what’s real and what is imagination. Already my vision fades to darkness.

As the black sheet falls, I wonder if the agony of dying is the last thing I will know of this world.

I REMAIN. The darkness has lifted. My eyes are open, though when I try to blink, they do not respond. The air is heavy with the sick-sweet scent of blood, but it does not fill my lungs. The sun is a fading memory, and I’m cold to my bones, cold to my soul. I do not think I will ever again be warm.

I am, I think, dead.

Dying, at least.

Someone is speaking, a voice that’s at once close and far, far away.

It’s Alexander, I realize. A voice I should know anywhere.

Abruptly I’m moving, the stars shake before my eyes.

Then it stops and my friend’s face is rising up over the stars. Tears have run clean rivers through the dirty soil upon his skin. “Hold on, Heph,” he’s saying. “Hold on.”

The shaking comes again, and the face and stars before me sweep wildly to left and right. Alexander is moving me, I think. He’s doing something.

Whatever it is, it must be too late. If I had air, I’d breathe my last whispering his name, but he knows. We’ve always known, he and I.

My vision stills again, and I see my friend lifting something up against the background of stars. He settles it toward my chest. I see what it is.

The stars dim. The Aegis descends.

It touches my flesh. And the darkness becomes a searing light that carries me away into sleep.

THE SUN DANCES UPON THE NILE. Sakhmakh is standing beside us on the riverbank as Terach and the others carefully load the crate containing the Ark onto a low-walled barge. I’d say that it is a miracle that Terach and I survived, but I know the power that preserves only too well. I know the darkness that has made us whole.

“It will be hidden where none will find it,” Alexander promises her. Whatever thoughts he might have entertained for using the Ark, he has told me, they disappeared when he saw what it did to me that night.

And what I did through it. Even now, days later, I am certain that the desert carrion are still glutted on the horror we left behind, the horror whose end I don’t even remember.

My inability to recall what happened, my paranoid suspicion that perhaps I was in some way only a vessel for the power of the Ark — as if its stone were a sentient being and I its puppet — does nothing to alleviate my guilt.

Somehow it makes it even worse.

“I know you will see that it is so,” the kandake says, and she kisses him on the cheek. Alexander, for all his conquests, seems embarrassed. Next she turns her smile to me. “And you, Lord Hephaestion, are owed much, too. We would not have survived if not for what you did.”

I smile, but I doubt it is convincing. In truth, even if I don’t know what happened later, I can still remember that initial surge of divine power coursing into my muscles, into my aching bones. A part of me wants to feel it again, even as another part of me simply wants to throw up. “I’m glad we survived,” I manage to say.

The kandake of Kush kisses me, too, in her gratitude.

Within minutes, the Ark is aboard the barge and all is ready to depart. Terach will travel with us, along with three other Jews. They will begin the construction of the new temple of the Ark. The surviving remainder of their secret company will return with Sakhmakh to Kush, there to make their final arrangements for their move to the new city that Alexander is building upon the sea, the new city with the greatest of treasures beneath its streets.

We set off onto the river. The man at the tiller uses a pole to push us closer and closer to the main flow of the mighty river, and then I feel its steady roll lift our weight and begin to carry as downstream. It is a great beast, this river, more powerful than any I have ever seen. But it is nothing like the power that flowed in me, that flowed through me. That power, I think, seemed as if it could have broken the world.

The banks rise and fall around us. I stand at the prow as the waves slip beneath the barge. Trees and fields appear and disappear. I see it all through a kind of blank stare, lost in my own thoughts.

“You’re quiet, Heph.”

Alexander. He’s walked up to stand beside me. He knows me too well for me to hide anything from him. “I was just wondering,” I say after a moment. “What next? Will you keep the Aegis?”

My friend chews on his lip — gods, what a terrible habit — and he watches a small farm pass by along the closer shoreline. “I’ve thought about that a lot,” he says. “I think I must. There may still be more for it to do. And my dream is still alive. They can bury it with me.”

I nod. It’s what I have suspected. I look up at the Egyptian sun. “And after the Ark is in Alexandria? What then?”

Alexander smiles. “Then we’ll leave this country,” he says. His eyes glint mischievously. “And maybe you’ll start sleeping through the night.”

“Out of Egypt,” I whisper. At once I think of green vineyards, of peace and home. And then, as if on cue, I’m aware of sandy grit in my hair and between my thighs. The thought of it makes me let out a tired sigh of a laugh. “Can’t happen fast enough.”

“By the gods, Heph, I’ve missed that sound.”

I smile. And beneath us, unaware of its burdens, the great river carries us on.

Author’s Note

As with the Shards of Heaven series of novels for which this story serves as a prequel, the tale here falls within the genre of Historical Fantasy. Even more particularly, it is what is often called a “Secret History,” since its characters and events are intended to fit within the bounds of known history to the highest degree possible.

For all his extraordinary impact and fame, there is much about the life of Alexander the Great that remains unknown. One of our questions — one that is more argued in our modern era than in his contemporary day — regards his potential bisexuality. The Macedonian king was thrice married, and it seems certain that he had multiple female lovers, but there is also some reason to think that he engaged in homosexual activity, as well. In particular, much interest focuses on Hephaestion (born ca 356 BC, died 324), who was Alexander’s closest friend, his fellow student under the tutelage of Aristotle, one of his finest field commanders, and quite possibly his lifelong lover. The two men could hardly have been more devoted to one another: by their own actions it seems clear that they perceived of their relationship as modeled upon that of the Homeric heroes Achilles and Patroclus, whose relationship has likewise been subject to speculation about its sexual nature. In addition, a letter to Alexander that is traditionally ascribed to Diogenes of Sinope, the philosopher briefly mentioned in this story, suggests that the Macedonian king was too devoted to “Hephaestion’s thighs,” an implicit recognition of a sexual relationship between the men based on the Greek eromenos model.

Another historical unknown is why in 331 — after Alexander had seized Egypt, after the king had visited the desert oracle at Siwa Oasis and apparently been declared the son of a god — his army turned back from marching up the Nile to defeat the prominent kingdom of Kush. It may be that Alexander simply saw little political, military, or economic benefit to conquering the African kingdom, but there has long been speculation that there was some other rationale for his actions. At least as far back as the so-called Romance of Alexander, a third-century text now ascribed to Pseudo-Callisthenes, there have been stories that Alexander’s armies were met in the desert by those of the kingdom of Kush. The kandake, or queen, of Kush appeared at their head, riding a great war elephant. Impressed, Alexander agreed to turn back from driving further south. Still later accounts suggest that the kandake and Alexander had a passionate romantic encounter. Very likely such stories are nothing but legend … though one must admit they make for an interesting background to a story.

The 332 siege at Gazza (modern Gaza) is a true event, as is the horrific shoulder wound that Alexander took there. Also true are the names of the kandake and the qore of Kush, the Greek leader who managed to learn Persian, and a host of other historical tidbits throughout this story.

The temple described here is also a real place: the Temple of Hibis, in the Kharga Oasis. Efforts are underway to restore its ruins, which include the magnificent carving of King Darius I of Persia described here. Also being restored is a line of battered stone sphinxes that line the road to the temple — not all of which are aligned as they should be.

Copyright © 2016 by Michael Livingston