opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window Take a road trip into a Southern gothic horror novel.

Take a road trip into a Southern gothic horror novel.

Titus and Melanie Bell are on their honeymoon and have reservations in the Okefenokee Swamp cabins for a canoeing trip. But shortly before they reach their destination, the road narrows into a rickety bridge with old stone pilings, with room for only one car.

Much later, Titus wakes up lying in the middle of the road, no bridge in sight. Melanie is missing. When he calls the police, they tell him there is no such bridge on Route 177 . . .

opens in a new windowThe Toll by Cherie Priest is on sale on July 9.

1

“What nobody ever tells you about gardening is . . . how many things you have to kill if you want to do it right.” Daisy Spratford jammed her spade into the earth, slicing a worm in two. She used the small shovel to toss one half toward the bird feeder, and the other toward the water fountain full of murky green water and the fish that somehow survived there, in the overgrown backyard of a house called Hazelhurst. “No one says how many bugs, how many beetles . . . how many naked pink things that might be voles, or might be mice. I don’t know the difference, when they’re little like that. They all look the same until they get some hair.”

“It don’t matter anyway,” said her cousin Claire. She didn’t look up from her knitting. She didn’t change the tempo of her foot, which leaned back and forth from heel to toe and back again, rocking her chair in time to the clicking of her needles.

“It matters to the crows, and the cats. It matters to Freddie, over there. It’s a service I provide them. It’s a kindness, is what it is.”

“Not if you’re a mouse.” Cameron sat on the porch’s edge, his feet maybe dangling right in front of Freddie, the resident king snake, for all he knew. He wasn’t bothered by Freddie, and he wasn’t particularly bothered by the thought of doomed pink rodents, writhing on his godmother’s spade. But he liked to be contrary. He shrugged at both old ladies. “Or a vole, or whatever. I was just saying, it’s all a matter of perspective.”

They gave him a flash of stink eye.

“Perspective.” Daisy’s drawl made the echo sound like a sneer. “My perspective is, I like having tomatoes come summer—and squash and cucumbers, too. My perspective is, I got pests enough without letting the stub-tailed pinkies grow up to be long-tailed brownies and breeding more of their kind. They don’t stay in the garden, you know. They duck under the house, and get inside the walls.”

“And inside Freddie,” Claire added, lifting a needle for emphasis. Daisy shook her head. “Not enough of them.” She stabbed something else with her spade, but it might’ve only been a root, or a clump of clay. “We’d need an army of Freddies to get them all.”

Cameron didn’t look. He wasn’t squeamish, but he didn’t care what Daisy was killing this time. He liked summer tomatoes, too, and he didn’t know anything about gardening—except for what Daisy told him, when she offered up her weird lessons while he looked on, sipping lemonade he’d mixed up with a splash of Jack.

His godmothers, each one past eighty years of age, surely knew about the Jack. They knew about everything else that went on within a hundred miles, so the whiskey wouldn’t come as any surprise; but they didn’t hide the bottle, so that was as good as permission.

The ladies had no trouble putting down their tiny feet when the fancy struck them. Seventeen was plenty old enough to drink, in Cam’s opinion. Seventeen was almost old enough to vote. Almost old enough to go to war. Neither activity sounded like something he’d go out of his way to do, but some people placed a lot of importance upon such things. Cam placed most of his importance upon clandestine sips of Jack.

Daisy adjusted her sun hat and shook a bag of seeds. A smattering sprinkled into her canvas-gloved palm.

Claire’s needles tapped together, full speed ahead. “It’s gonna rain.”

“So what if it does?” Daisy wiped a smear of sweat from her forehead, though it wasn’t very warm. Certainly not as warm as it’d be in a month, or in another month after that. Hell, the mosquitos were barely even out. It was barely even spring.

She glanced at Cam. “When the rain comes, I’ll need help getting inside.”

“You know I’ll take care of you, Miss Claire. You feel the first sprinkle,” he vowed, “and I’ll whisk you off to the parlor.”

“That’s a good boy. Mostly.” She peered down at the project dangling from the needles. It was finally taking shape—green and gray. Not a mitten or a scarf. Not a blanket for a baby. It was already too warm for any of those things, anyway.

The town of Staywater was always both too warm, and not warm enough.

Cameron wondered if it was just him, or if everybody felt that way. Hazelhurst had air-conditioning units in half its windows and gas heat that came up from the floors, but he couldn’t remember the last time he’d heard either one of those systems running. God only knew if they even still worked.

His swinging feet picked up a rhythm. Claire’s needles followed along, unless it was the other way around.

One-two. One-two. One-two.

If this weather was some kind of sweet spot, it could stand to be sweeter. He thought about taking off his shirt—a striped button-up with long sleeves, rolled up his forearms. He thought about going inside and getting a sweater.

He thought about.

The needles pulled the yarn, loop by loop. Claire’s foot leaned.

“He’s wandering again,” Daisy murmured.

Claire murmured back, “He’s bored.”

“It’s a boring town for a boy his age. In another few years, he’ll kill time down at Dave’s place—whatever they call it now— and he won’t have to reach into the cabinet, feeling good about stealing. He does feel good about it, you know.”

“He kills plenty of time at Dave’s already, but I don’t think they serve him. He goes down there to see that woman.”

Daisy clucked her tongue. “She’s trouble. Anyway, she’s too old for him.”

“She agrees about that, so it’s one thing we got in common. Someday, we should tell him who she is, and what she’s done. He might not believe us, but then again, he might. Might make it easier for him to leave, when the time comes for that.”

Daisy snapped, “You hush your mouth.”

Cam stared into space. His feet kept time with Claire’s lone foot, pumping against the weight of the rocker; but Cam’s heels knocked against the lattice that screened off the porch’s underside. It was thin with dry rot, and flaky with old lead paint. It cracked under the percussion of his heels, but he didn’t stop.

“We may as well get used to the idea,” Claire said. “He’s growing up, and he might not stay. It’d be best if he didn’t. You know it as well as anybody.”

“But they always do. Now that it’s safe.”

She shook her head. “No. They don’t.” Her needles knotted the yarn, row upon row. “And you don’t know that it’s safe.”

Daisy’s spade cut the garden dirt, row upon row. “They usually do,” she amended her conviction. “And it mostly is. Besides, where else would he go?”

“Forto. The swamp park. Somewhere farther off than that. Anywhere he wants, I guess.” Claire peered over her shoulder. Cam’s feet bumped up and down, back and forth. The lattice held just fine. If Freddie was under there, he held just fine, too. Probably, he’d taken off already—retreating to some quieter corner under the front steps, where bigger things than pinkies burrowed.

“Cameron wouldn’t leave us here, all by ourselves.”

“We won’t live forever. Hell, we won’t live that much longer.”

“No, we won’t.” Daisy clenched her jaw, and squeezed her spade. She bore down on a cricket until it was nothing but damp black chunks that squirmed, then stopped. “But as long as he knows the rules, and knows to follow them when it counts . . . he can stay right here with us.”

Claire didn’t feel like fighting, or else she was losing track of her rhythm because Cam cleared his throat. “You thirsty, baby?” she asked him. “Maybe go on inside, and get yourself another glass of lemonade.”

“I’m . . . I’m all right for now.”

He still had half a glass. Dwindling cubes of ice clattered together when he spun it in his hand. Condensation soaked between his fingers, and dribbled down his wrist. He took another swallow—a long one that burned this time—and with two more just like it, he’d finished off the glass. He held it up and wiggled it; the ice cubes crunched against each other, and melted into slush.

“Would you like another one?” Daisy asked.

“No, ma’am, that’ll be enough. And would you look at that, the very first drops of rain are just coming down. You were right about the weather, Miss Claire. I probably ought to help you get inside.”

“It’s only a sprinkle,” she replied with a squint at the sky. “But it’ll get worse, before it goes away. All right, hand me my knitting bag. If there’s any breeze at all, I’ll get soaked up here.”

He stood up and stretched, then picked up the cotton satchel full of needles, balls of yarn, and whatever else old women toted around when they planned to make something, or acted like they were going to. He slung it across his chest and bent down to help Claire, who was a little fat and very arthritic, and maybe didn’t need as much help as she pretended—but he didn’t mind, just in case she did. Her cane was beside the knitting bag, but she always said how getting up and down was hard without a hand like Cameron’s.

Daisy was on her own, and that was just how she liked it. But he called back to her: “Would you like me to come help? When I’ve got Miss Claire sorted out?”

She shook her head. “I’m all right. It’s hardly damp at all, and there isn’t much to put away.”

He took her at her word, and assisted godmother number one to her favorite chair by the lamp with a shade she insisted was a valuable piece of Tiffany, but was more likely a plastic piece from Woolworth’s. The sky was overcast and the house’s interior was dark, though it wasn’t late and wasn’t early—so Cam turned it on for her, figuring she’d go back to the knitting, or else to one of the books she kept within reach of her preferred perch.

Daisy had told him not to bother helping her pick up the gardening, but he went back out there regardless. Besides, he’d left his glass on the porch, right by the rail. If she saw it, he’d never hear the end of it

He watched her, thin and hunkered, but stronger than she looked. She pulled a wagon with a seat on it, and all her gardening tools loaded up inside; she drew it toward the storage shed with a roof so rusted it hardly gave any shelter at all—but technically, it was better than nothing. Her hat sagged and bounced with every step.

He retrieved his lemonade glass and tossed the mushy ice into the yard.

The rain wasn’t coming down any harder, and he didn’t believe that Claire was right when she’d predicted that the weather would get worse. He poked his head back into the house. “I think I might go into town, if it’s all the same to you,” he announced.

“Wait for Daisy to . . .” Claire began, but stopped when she heard her cousin’s footsteps on the porch. The boards creaked and stretched beneath her, and the handrail strained.

“Wait for Daisy to what?” she called as she climbed.

“I was going to say, he should wait for you to come back inside . . .” Claire hollered. She dropped her voice when Daisy appeared in the doorway.

“You’re getting paranoid in your old age.”

“What if you fell? What if you broke a hip out there, and Cameron was halfway to the square? I wouldn’t be any help at all.”

Cam chimed in. “You’ve got your cell phone.”

“I can hardly use that thing.”

He grinned. “You used it just fine when you wanted pizza last Friday.”

Daisy sighed loudly and shut the screen door behind herself. She leaned against the frame and picked dirt from under her nails. “I’ve got mine in my apron pocket, and I’m not afraid of the buttons anymore. Don’t worry about us,” she said to Cam. “We’re fine, same as always.”

“Same as always,” he echoed.

Everything in Staywater, always the same as always.

He swiped a light jacket from the coatrack, in case he needed it. He pushed the screen door open again and saw himself out, then latched it back into place. If the ladies had wanted him to close the front door, one of them would’ve said so. Then the other would’ve argued. Then they would’ve bickered about it so long, by the time they’d come to some agreement, it’d be the middle of the night and Cam would still be standing there, waiting for them to reach a consensus.

Just like always.

Cameron Spratford had lived with Claire and Daisy since he was a toddler. His parents had left him there at Hazelhurst one day, leashed to the front door’s knob like a puppy abandoned at the pound.

Unless it wasn’t his parents who’d dropped him off in a ding-dong-ditch. Really, it could’ve been anyone.

And it could have been worse. When he was especially bored, he would consider the alternatives in great and terrible detail, imagining his small self the victim of vast, unspeakable horrors. He could’ve been leashed to a canoe and set adrift in the nearby swamp. He might’ve been swaddled and dumped in one of the many abandoned buildings that Staywater boasted, now that its heyday had long ago passed. Someone might have even left him in the south Georgia woods, tethered to a tree, waiting for wolves.

Did they have wolves in Georgia?

He paused, and stared thoughtfully at the sky. A faint mist dampened his face. He swiped it away with the back of his forearm.

Probably not, he concluded.

Coyotes, then. He might’ve been raised by coyotes, or deer, or whatever else might be big enough to manhandle a toddler. Wouldn’t that have been weird? It might’ve been fun, or it might’ve been awful. He’d never know for certain, because instead of a wildlife upbringing or hasty devouring, he’d received the Spratford cousins, doting and batty—but no more batty than anyone else within the city limits, he had to admit.

He strolled down the dirt-and-gravel drive that ran almost half a mile to the main road, swinging a black umbrella by the U-shaped crook of its handle. He spun it in his hand, and tapped the ground. Once. Twice. In time with his pace, like a cane— but not like Claire’s. The umbrella was just for show. Cameron didn’t have anywhere to be, but Hazelhurst was stifling and the ladies were stifling, too. It didn’t matter if they meant well. Hell, didn’t everybody mean well?

Maybe not, he considered darkly.

Come to think of it, maybe not even them.

Copyright © 2019 by Cherie Priest

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

– Horror Stories By Richard Matheson

– Horror Stories By Richard Matheson

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Cherie Priest

by Cherie Priest

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Brian D. Anderson

by Brian D. Anderson by Jason Denzel

by Jason Denzel by Jason Denzel

by Jason Denzel by Heather Graham & Jon Land

by Heather Graham & Jon Land

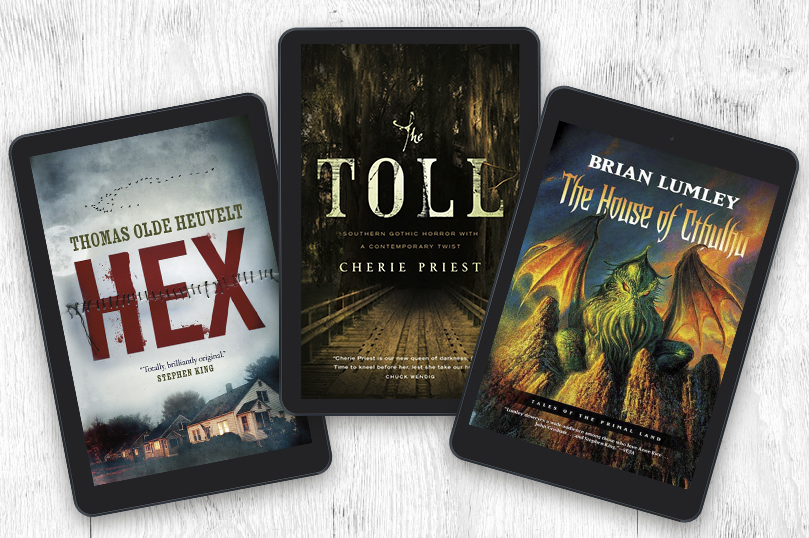

HEX

HEX The Toll

The Toll Burn the Dark

Burn the Dark I Am Legend

I Am Legend Night of the Mannequins

Night of the Mannequins The Monster of Elendhaven

The Monster of Elendhaven

Alone with the Horrors

Alone with the Horrors Hell House

Hell House HEX

HEX The Mothman Prophecies

The Mothman Prophecies The Keep

The Keep Dark Harvest

Dark Harvest Legion

Legion I Am Not A Serial Killer

I Am Not A Serial Killer

The Family Plot

The Family Plot The First Days

The First Days Nightflyers & Other Stories

Nightflyers & Other Stories Stranded

Stranded The House of Cthulhu

The House of Cthulhu The Five

The Five