Welcome to Throwback Thursdays on the Tor/Forge blog! Every other week, we’re delving into our newsletter archives and sharing some of our favorite posts.

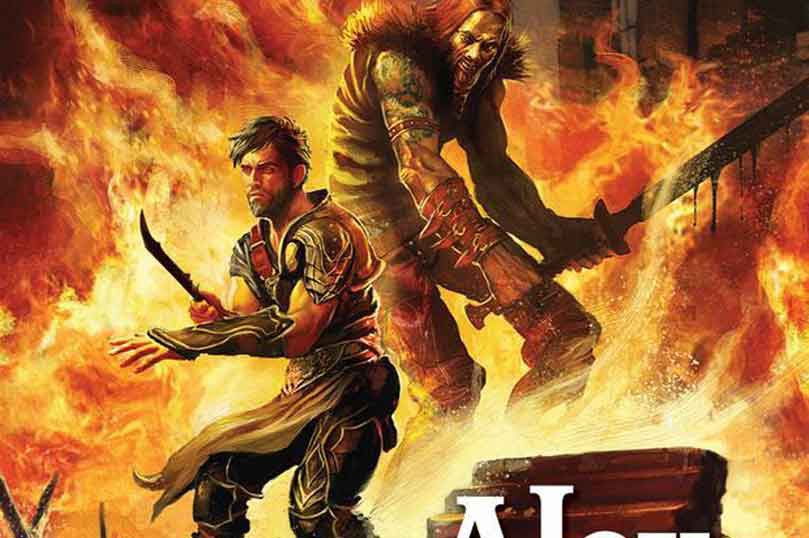

Vlad Taltos is back in Steven Brust’s Hawk! In the opens in a new windowNovember 2007 Tor Newsletter, author Steven Brust talked about the characters—and the animals they’re similar to—he’s created over the years. Be sure to check back in every other week for more!

By Steven Brust

By Steven Brust

Why is it that I put animals in my books, or, more particularly, put in people with some sort of symbolic relationship to an animal? Is it because, in human history and pre-history so many people identified themselves with animals? No, that’s the justification, not the reason.

Is it so I can explore the animal nature within us all? Yeah, right, whatever.

Is it that it makes it easier to explore what it really means to be human? No, but if the New York Review of Books ever interviews me, that’s what I’ll say.

No, it’s so I can make fun of my friends without them knowing about it.

In the world in which the Vlad Taltos novel is set, the population is divided into what are called Great Houses, each named for an animal. Some of these animals are familiar to us all, some are made up, and some are familiar but altered. In truth, all human beings are a delightful mix of personality traits, some of which can appear dominant at various times depending on circumstances. In fiction, particularly fantasy, I get to exaggerate characteristics and make animal comparisons, and when I need to, make up the animal—all for the pleasure of laughing at my friends. I love this business.

Like, that guy who cares just a bit too much about money? Orca. The one with the temper? Dragon. The manipulative bastard? Yendi. The guy with ethics but no principles? Jhereg. The one who would cut off an arm rather than be rude? Issola. I don’t know about you, but I’ve had hours of fun figuring out which House all of my friends belong in.

My latest Vlad Taltos novel—out in paperback this month—is called opens in a new windowDzur. A dzur is your typical big, nasty cat. The people who identify with it are of the House of Heroes.

What, exactly, do I mean by “hero?” I’m not talking about real heroes, because real heroes only happen where character meets circumstance. Nor am I talking about people who constantly look for situations where they can show off their courage—they aren’t heroes, they’re adrenaline junkies. By “hero,” in this context, I mean someone who always goes in with the odds against him—in fact, who only goes in when the odds are against him. Sounds good, right?

You know them. At a party, he’s the one who won’t venture an opinion unless he’s pretty sure everyone in the room is on the other side. On the highway, he’s the ones zipping down the empty lane that’s about to vanish for construction, expecting you to let him in. On the internet—Oh, lord. Don’t get me started. Yeah, these are the guys who have raised being unpopular to an art form. One of my dearest friends is a Dzur. He sometimes refers to himself as Captain Social Suicide. Need I say more?

So, yeah, anyway. Those guys. They’re annoying as hell, but in stories they’re kinda fun.

This article is originally from the November 2007 Tor newsletter. Sign up for the Tor newsletter now, and get similar content in your inbox every month!