opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

In a snowbound inn high in the Alps, four people meet who will alter fate.

In a snowbound inn high in the Alps, four people meet who will alter fate.

A noble Byzantine mercenary . . .

A female Florentine physician . . .

An ageless Welsh wizard . . .

And Sforza, the uncanny duke.

Together they will wage an intrigue-filled campaign against the might of Byzantium to secure the English throne for Richard, Duke of Gloucester—and make him Richard III. Available for the first time in nearly two decades, with a new introduction by New York Times-bestselling author Scott Lynch, The Dragon Waiting is a masterpiece of blood and magic.

Please enjoy this free excerpt of opens in a new windowThe Dragon Waiting, on sale 09/29/2020.

Chapter 1

GWYNEDD

THE ROAD THE ROMANS made traversed North Wales a little way inland, between the weather off the Irish Sea and the mountains of Gwynedd and Powys; past the copper and the lead that the travel-hungry Empire craved. The road crossed the Conwy at Caerhun, the Clwyd at Asaph sacred to Esus, and the Roman engineers passed it through the hills, above the shore and below the peaks, never penetrating the spine of the country. Which is not to say that there were no ways in; only that the Romans did not find them.

From Caernarfon to Chester the road remained, and at Caerhun in the Vale of Conwy there were pieces of walls and straight ditches left where the legionary fort had held the river crossing. Roman stones, but no Romans; not for a thousand years.

Beyond Caerhun the road wound upslope for a mile, to an inn called The White Hart. Hywel Peredur lived there in this his eleventh year, the nine hundred tenth year of Arthur’s Triumph, the one thousand ninety-fifth year of Constantine’s City. This March afternoon, Hywel stood on the Roman paving below the innyard, and was King of the Romans.

Fields all his dominion rolled out forever before and below him, lined and set with trees that from the height were no more than tufts on a cloth of patchwork greens and browns. Conwy water was a broad ribbon stitched in easy curves across the cloth. The March air smelled of peat and moisture and nothing at all but its own cold cleanness on the sharp edge of spring.

The place Hywel stood was called Pen-y-Gaer, Head of the Fortress. There had been a fortress, even before the legions came; but of its builders too only stones were left, bits of wall and rampart. And the defense of the slope, a field of sharp-edged boulders set in ranks down the hill.

Hywel stood on the road and commanded the stones, soldiers without death or fear, like the warriors grown from dragon’s teeth in the story; any assault against them would break and be scattered. Then, at Hywel’s signal, his legion of horse would gallop forth from Caerhun and cut down the discomfited enemy, sparing only the nobles for ransom and tribute. His captains, in purple and gold, mounted on white horses, would drive the captive lords before him, shouting Peredur, Peredur! that all might know who was conqueror here. . . .

Not far up the road was a milestone; it was worn and half-legible, and Hywel knew no Latin, but he could read the name constanti. Constantine. Emperor. Founder of the Beautiful City. And now a god, like Julius Caesar, like Arthur King of Britain. Hywel would run his fingers in the carved letters of the name when he passed the marker, touching the figure of the god.

Three years ago, on the May kalend, he had stunned a sparrow with a sling pellet, bound its wings, and taken it to the milestone. It had trembled within his shirt, and then, when he set it down, become curiously still, as if waiting. But Hywel had had no knife, and was afraid to use his naked hands. By the time he had found two flat stones and done the thing, he could no longer remember his intended prayer.

Now, clouds drifted across the low sun, making shadow patterns on the ground. The river dulled to slate, then flashed bluesilver. The standing stones seemed to move, to march, beat spears on shields in salute. Sparrows were forgotten as Hywel moved his cohorts, as soldier and king and god.

Until dust rose, and men moved crosswise to the dream, light flashing on steel: real soldiers, on the road to the inn. Hywel watched and listened, knowing that if he were quite still they could not detect him. He heard the scrape of pikes on the paving stones, the stamp of booted feet, chains dragging. He let the breeze bring him their voices, not distinguishable words but rhythms: English voices, not Welsh. As they turned the last bend in the road, Hywel’s eyes picked out the badge they wore. Then he turned and ran lightly to the gate of The White Hart. As he crossed the innyard, a dog sniffed and raised its head for a pat that was not coming; sparrows fluttered up from the eaves.

The cruck-beamed serving hall was dim with afternoon. A little peat smoke hung in the air. Dafydd, the innkeeper, was working at the fire while Glynis, the pretty barmaid, wiped mugs. Both looked up, Glynis smiling, Dafydd not. “Well, my lord of the north, come in, do! While you’ve been with your councillors, this fire nearly—”

“Soldiers on the road,” Hywel said, in Welsh. “My lord of Ireland’s men, from Caernarfon.” He knew Dafydd’s anger was only mocking; when the innkeeper was truly angry he became deadly quiet and small-spoken.

“Well, then,” said Dafydd, “they’ll be wanting ale. Go you and draw a kettleful.”

Hywel, grinning, said, “And shall I fetch some butter?”

The innkeeper smiled back. “We’ve none that rancid. Now draw you the ale; they’ll not care to wait.”

“Ie.”

“And speak English when the soldiers can hear you.”

“Ie.”

“And give yourself a whipping, lad—I haven’t time!”

Hywel paused at the top of the cellar stairs. “There’s a prisoner with them. A wizard.”

Dafydd put the poker down, wiped his hands on his apron. “Well then,” he said quietly, “that’s bad news for someone.”

Hywel nodded without understanding and clumped downstairs. He drew the ale into a black iron kettle, put it on the lift and hoisted it up; and only then, standing in the quiet cellar, did he realize just what he’d said. He had heard the chains, right enough, but never once seen what was in them.

***

Eight men, and something else, stood in the innyard.

The men wore leather jackets, carried swords and pole axes; two had longbows across their backs. One, helmeted and officious, had a long leather pouch at his side, and a baldric from which little wooden bottles hung on strings. Charges of powder, Hywel knew, for the hand-cannon in the pouch.

The badge on the soldiers’ sleeves was a snarling dog on its hind legs; a talbot-hound, for Sir John Talbot, the latest Lieutenant of Ireland. Talbot had smashed the Côtentin rebels at Henry V’s order; it was said the mothers of Anjou quieted their children with threats of Jehan Talbó. Now that Henry was dead, long live Henry VI, and the advisors to the three-year-old King hoped the War Hound could quiet the Irish as well.

Four soldiers held chains that led to the other thing, which crouched on the ground, black and shapeless. Hywel thought it must be some great hunting-hound, a namesake talbot, perhaps, or a beast from Ireland across the sea; then it put out a pale paw, spread long fingers, and Hywel saw it was a man on hands and knees, in fantastically ruined clothes and a black cloak.

The thin hands left blood on the earth. There was a shackle, engraved with something, on each wrist and each ankle, linked to the leash-chains. The head turned, and the black hood fell back, showing dull iron around the man’s neck. The collar was engraved as well. Next to it was a straggly gray beard, a nostril with blood dry around it.

Hywel stared at a dark eye, glassy as with fever, or madness. The eye did not blink. The cracked lips moved.

“None of that, now!” shouted a soldier, and pulled the chain he held, dropping the man flat; another soldier swung the butt of his axe into the man’s ribs, and there was a hint of a groan. The first soldier bent halfway down and shook the chain. “ ’Tain’t beyond th’ law for us to have your tongue, an you try any chanteries.” To Hywel he sounded exactly like Dafydd’s wife Nansi scolding a hen that would not lay. The prone man was very still.

“Ale! Where’s ale!” cried the others, turning away from the prisoner, and Dafydd came behind Hywel with a tray of tankards, hot mulled ale topped with brown foam and steaming. “Here, Hywel. And Ogmius send us all the right words to say.” Hywel took the tray into the yard. A cheer went up—for him, he realized, and for one passing instant he was Caesar again—then the mugs were snatched from him.

“Here, boy, here.”

“Jove’s beard, that’s good!”

“Jove strike you down, it ain’t English beer.” The speaker winked at Hywel. “But it’s good anyway, eh, boy.”

Hywel barely noticed. He was staring again at the chained man, who still did not move except to breathe raggedly. A little of the cloak had blown back, showing the man’s shirt sleeve. The fabric was embroidered in complex patterns—not the Celtic work he knew, but similar, interlocking designs.

And The White Hart was an inn with good trade; Hywel had seen silk twice before, on the wives of lords.

“You have a care of our dog, there, lad,” said the soldier who had winked. His tone was friendly. “He’s an eastern sorcerer, a Bezant. From the City itself, they say.”

The City of Constantine. “What . . . did he do?”

“Why, he magicked, lad, what else? Magicked for th’ Irish rebels ’gainst King Harry, rest him. Five years he hid up in them Irish hills, sorcellin’ and afflictin’. But we ketched him, anyway. Lord Jack ketched him, an’ now he’s Talbot’s dog.”

“Tom,” the serjeant said sharply, and the soldier stood to attention for a moment. Then he winked at Hywel again and tossed his empty tankard into Hywel’s hands.

“Have a look here, boy,” Tom said. The soldier reached down and grasped the manacle around the wizard’s left wrist, pulled it up as if there were no man attached to it. “See that serpent, cut there in th’ iron? That’s a Druid serpent, as has power t’ bind wizards. Old Irish Patrick drove all the snakes out of Ireland, for the good of his magic fellows. But we took some snakes with us. Snakes of leather, an’ iron.” The soldier let the shackle fall with a hollow clunk. The prisoner made no sound. Hywel stood fascinated, wondering.

“Innkeeper!” the serjeant said.

Dafydd came out, wiping his hands on his apron. “Yes, Captain?”

The serjeant did not correct his rank. “Have you a blacksmith here? This rebel’s harmless enough, but he’ll crawl off with half a chance given him. We’ll want him fixed to something with weight.”

“You’ll be staying here for a time, then?”

“We’re in no hurry. The prisoner’s to be taken to York for execution.”

A soldier said, “The Irish Sea were deep enough.”

“Not to bury his curse, man,” said the serjeant curtly. “Leave killing him to his own sort of worker.” He turned back to Dafydd. “Don’t worry about the lads, innkeeper; they’re good and they’ll obey me.” He weighted the last word slightly. “And they’re bloody tired of minding this rebel.”

“Hywel,” said the innkeeper, “run you and tell Siôn Mawr he’s wanted, with hammer and tongs.”

A high-voiced young soldier called after Hywel, “And you tell ’im this aren’t no horse wanting shod! A hammer on them chains—”

Hywel ran. He did not look back. He was afraid to. Under all the soldiers’ voices, under Dafydd’s, under his own breathing, he could hear another voice, whispering, insistent, like the beat of blood in his ears when all was still. He had heard it without pause since the sorcerer’s lips had moved without sound.

You who can hear me, it said, come to me. Follow my voice.

And as Hywel ran through the gathering dark, it seemed that hands reached after him, grasping at his limbs, his throat, trying to draw him back.

***

Nansi touched the spit-dog’s collar; it stopped walking its treadle, and Nansi carved a bit of mutton from the roasting haunch. The dog resumed turning the meat. Nansi put the mutton on a wooden plate with a spoonful of boiled corn, added a piece of soft brown bread.

“The soldiers didn’t pay for no meat for him,” said Dai, the kitchen boy.

“You needn’t tell me what they’ve not paid for,” Nansi said, tenting a napkin over the plate. “I hope he has his teeth; I daren’t send a knife. Here, Dai, go you quick, ere it’s cold.”

“Why do they beat him, if he can’t magic?”

“I’m sure I don’t know, Dai,” Nansi said, with a bitter look. “Take it, now.”

“I’ll take his dinner,” Hywel said, from the kitchen door. Dai’s mouth opened, then shut.

Nansi turned away. “I’ve drawn his water,” Hywel said. “And I’m not afraid of him. You’re afraid, aren’t you, Dai?”

Dai’s pudgy hands tightened. He was a year or so older than Hywel, and also an orphan. Dafydd and Nansi, who had no children, had taken them in together, and tried to bring them up as brothers. Hywel could no longer remember what that was like, even when he tried.

Dai said “Ie, feared enough. You feed him.” He handed the covered plate to Hywel, who took it with a nod. Hywel did not hate Dai; usually he liked Dai. But they were not brothers.

Just outside the kitchen, he picked up the hooded lantern and pot of ale he had set by the door, and crossed to the barn. Moonlight slanted across the interior. The wizard was sitting up against a post, all white and black in the light. His head turned slightly; Hywel held very still. The face was a skull’s, with tiny glints in the eye sockets.

Hywel hung the lantern from a peg and opened the shutter; the wizard winced and turned his face away.

It was all he could turn. A chain went through his collar, twice around the post and his upper body, holding him upright. The chains from his ankles were fixed to two old cart wheels. Hywel had seen Siôn Mawr the smith going home, and could not have missed the murder-black look Siôn gave him; now he understood it.

“It was you after all,” the chained man said, and Hywel nearly dropped the food. “Is that for me?”

Hywel took a step. The voice in his head was gone, but he still felt somehow drawn to the wizard. He stopped. “The soldiers say you can’t work magic, in those chains.”

“But you know better, don’t you?” His English had only a little foreign sound. “Well, they’re mostly right. I can’t do much, and I truly can’t escape. Come here, boy.” He moved his hands. Hywel turned away, not to see the sign.

“At least put my supper in reach. Then you may go. Please.”

Hywel moved closer, looked again at the wizard. The cloak was spread out beneath the man; it was lined with glossy black—more silk. Beneath the cloak he wore a dark green gown of heavy brocade, torn at every seam, showing the white silk shirt. Gown and shirt were embroidered all over with interlocking lines in gold and silver thread, with brighter colors worked between. The patterns drew Hywel’s eye despite himself.

He set the plate down in the straw, uncovered it. The man’s eyes widened, becoming very liquid, and he ran his tongue over very white teeth specked with dirt. He reached out, one-handed. Hywel saw that his wrist chains were linked behind his back. The wizard set the plate in his lap, and his delicate fingers hovered over it, talonlike, straining; there was not enough chain for his two hands to touch.

Hywel thought of offering to feed him, but could not say it.

The hands ceased to strain then. The wizard groped for and reached the napkin, shook it out, and arranged it as best he could over his shiny, filthy shirt. Then the thin fingers picked up a single kernel of corn and raised it to the swollen mouth. He chewed it very slowly.

Trying not to watch the wizard’s hands or eyes, Hywel uncapped the pot of ale. He took a twist of greasy paper from his belt pouch, opened it, and slipped the white butter within into the blood-warm ale. He stirred the pot with a clean straw and pushed it as close to the man as he dared. The wizard waited for Hywel to draw back, then picked up the ale and took a small sip. His eyes closed and he pressed his head back against the post, loosening the iron at his throat just slightly.

“Nectar and ambrosia,” he said. “Thank you, boy.” He put the ale down and picked up the mutton, took small, worrying bites.

Finally Hywel said, “You called me by magic. No one else could hear. . . . Why?”

The man paused, sighed, wiped his hands and lips. “I thought you were . . . someone else. Someone who could help.”

“You thought I was a wizard?”

“I called to the talent. . . . It spent me before I heard the answer. Hard to work with a boot in your ribs.” He reached for the bread, nibbled.

“I’m not a wizard,” Hywel said.

“No. I’m sorry. But I am glad you brought me this supper.”

They sat for a little while like that, the wizard eating slowly, Hywel crouched, watching him. To Hywel it seemed the man wanted to make his supper last all night. He said, “You thought I was a wizard.”

“I believe I explained that,” the man said patiently. “Isn’t it late for you to be awake still?”

“Dafydd doesn’t care, long as the fire doesn’t go out. You said it was somebody else you called. But I heard you. You called me.”

The man swallowed, licked his damaged lips. “I called to the talent. The power. It . . . radiates, like the light from a candle. I felt it, and answered back. That’s all.”

“Then I am a wizard,” Hywel said, breathless, triumphant.

The man shook his head, rattling iron. “Magus latens . . . no. Someday you could be, if you were taught. But now . . .” There was a noise within his throat that might have been a laugh. “Now you’re catalyzed. And I did it, now that I would not do it.”

Hywel said “Could you teach me?”

Again the choked laugh. “Why do you think I’m in chains, boy? I’d be dead now if they didn’t fear my death-curse so, and my tongue and eyes aren’t sure through tomorrow. Go to bed, boy.”

Hywel put his foot against one of the cartwheels chained to the wizard’s feet. He pushed. The chain shifted; in a moment it would be taut. It was astonishingly easy.

“Please,” the man said, “don’t.” There was no pleading in it, nor command. Hywel turned, saw the dark eyes ringed white and red, the face white as bare bone. And he stopped pushing. Perhaps if sparrows had voices . . .

“I am very tired,” the man said. “Please come tomorrow, and I will talk with you.”

“Will you tell me about magic?” Hywel’s foot was still on the wheel, but it had suddenly become very heavy and hard to move.

The man’s voice was weak, but his eyes were black and burning. “Come back tomorrow and I will tell you all I know about magic.”

Hywel picked up the plate and napkin, the ale pot. He stood, moved away backwards.

“My name,” said the wizard, “is Kallian Ptolemy. With the letter pi, if you can write.” Hywel said nothing. Everyone knew that wizards gained power by knowing names. He took the lantern from its peg, shuttered it.

Kallian Ptolemy said “Good night, Hywel Peredur.”

Hywel did not know whether to shudder or cry for joy.

Copyright © John M. Ford 2020

Pre-order The Dragon Waiting Here:

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

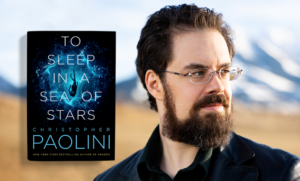

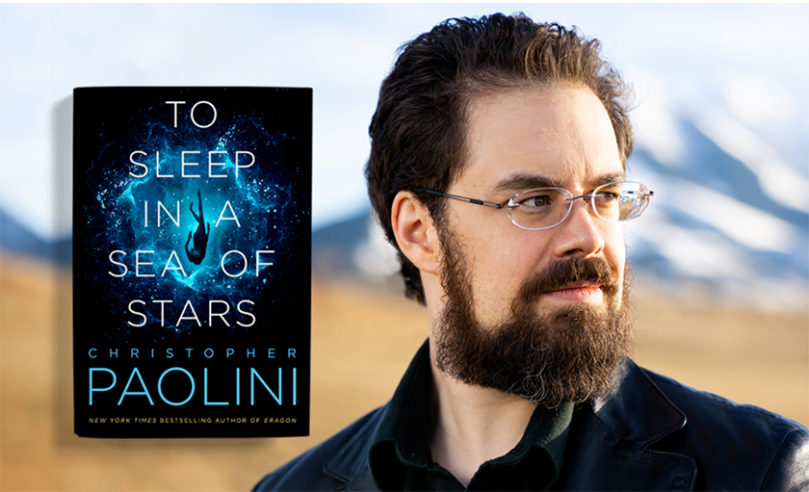

MARTIN: Did you consider what your cover would/should look like at any point during the writing process? If so, what did you have in mind and how does the final cover compare or contrast with your vision?

MARTIN: Did you consider what your cover would/should look like at any point during the writing process? If so, what did you have in mind and how does the final cover compare or contrast with your vision? PAOLINI: How did you become a book designer? Did you go to school to learn these skills, learn on the job with a publisher, or apprentice with someone? Are you self taught?

PAOLINI: How did you become a book designer? Did you go to school to learn these skills, learn on the job with a publisher, or apprentice with someone? Are you self taught? opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

Everything is change and everything ends, but can old things become new again?

Everything is change and everything ends, but can old things become new again?

Essun and the Orogenes —

Essun and the Orogenes —  General Shuos Jedao —

General Shuos Jedao —  Caliban —

Caliban —  The Archive —

The Archive —  Takeshi Kovacs and the Envoys —

Takeshi Kovacs and the Envoys —

A legend begins in Dune: The Duke of Caladan, first in The Caladan Trilogy by New York Times bestselling authors Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson.

A legend begins in Dune: The Duke of Caladan, first in The Caladan Trilogy by New York Times bestselling authors Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson.

In a snowbound inn high in the Alps, four people meet who will alter fate.

In a snowbound inn high in the Alps, four people meet who will alter fate.

L. E. Modesitt, Jr. is a force within the science fiction and fantasy community, but did you know his first dream was poetry? Check him out as he discusses his journey below!

L. E. Modesitt, Jr. is a force within the science fiction and fantasy community, but did you know his first dream was poetry? Check him out as he discusses his journey below!

Start reading bestselling author Cory Doctorow’s Attack Surface with

Start reading bestselling author Cory Doctorow’s Attack Surface with