2019 has been a wild year so far, and it’s made a lot of us crave well…a different timeline. Thankfully, Tor authors Annalee Newitz and Alison Wilgus have wrote this year about one of our all-time favorite SFF subjects: TIME TRAVEL.

So…Why time travel?

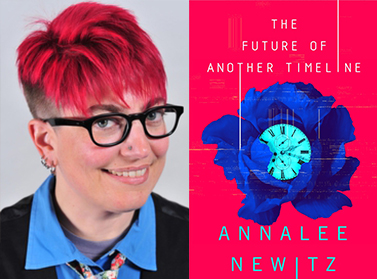

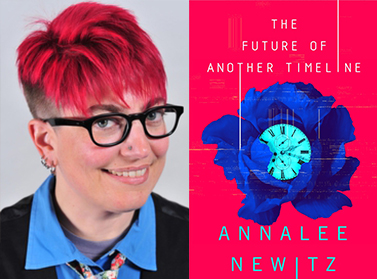

Annalee Newitz ( opens in a new windowThe Future of Another Timeline):

Honestly, I never wanted to write about time travel—it’s so difficult to plug up all the plotholes. But then I conceived of this alternate timeline, where my characters live, and realized that the only way it could have happened was because of time travel. So I kind of tricked myself into it.

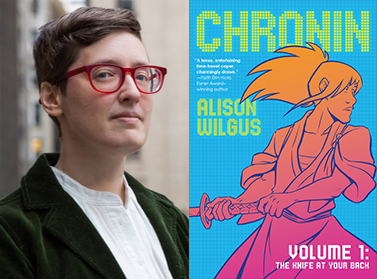

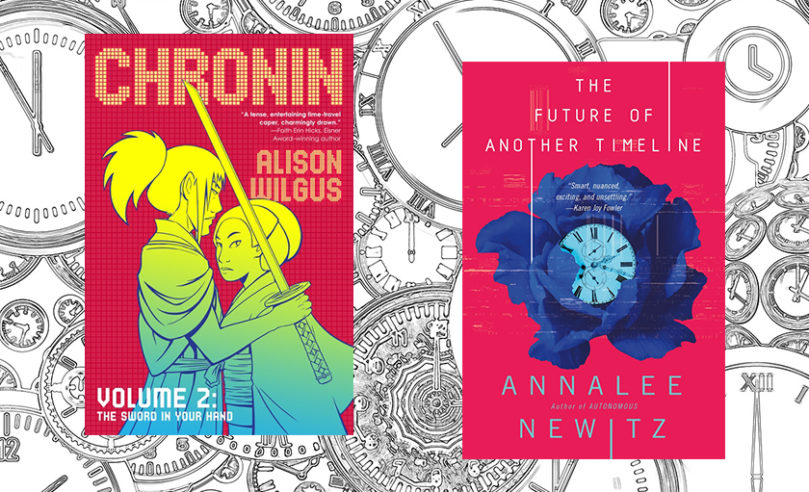

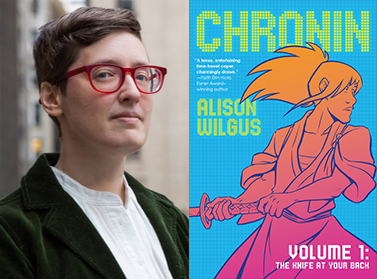

Alison Wilgus ( opens in a new windowChronin, Volumes 1 and 2):

It’s a mechanism that keeps sneaking up on me honestly—I’ll start out building a story about some other thing entirely, and then whoops, turns out that time travel is once again necessary to make the machinery of the story work. Different systems, different genres, radically different plots, but I just can’t seem to resist hurtling my characters around through time. That said, I do think there are some core themes that knit all these stories together, themes which I’m clearly interested in — most time travel stories are about exploration, or regret, or control. Chronin has a little bit of all three — the mechanism is a time travel program used by academics, and the antagonists are either picking at the scabs of the past or desperately trying to reshape the future.

It’s a mechanism that keeps sneaking up on me honestly—I’ll start out building a story about some other thing entirely, and then whoops, turns out that time travel is once again necessary to make the machinery of the story work. Different systems, different genres, radically different plots, but I just can’t seem to resist hurtling my characters around through time. That said, I do think there are some core themes that knit all these stories together, themes which I’m clearly interested in — most time travel stories are about exploration, or regret, or control. Chronin has a little bit of all three — the mechanism is a time travel program used by academics, and the antagonists are either picking at the scabs of the past or desperately trying to reshape the future.

What were some of the challenges of writing time travel?

AN: Definitely plotting was the hardest part for me. In the world I built, time travel is mundane and has been going on for thousands of years. So everybody knows that history is constantly being edited, though there is some debate over how much and how difficult it is. Plus, it takes years to become a time traveler so it’s not like anybody can just jump into a Machine and muck things up. I kept finding myself having to explain how time travel works, including paradoxes and limitations and the Machines themselves—and that’s hard to do without boring infodumps. I still think there are some plotholes in the book. The fun part was researching the different periods my characters visit, like Chicago in 1893 and Petra in 13 BCE. I love research. It’s my favorite way to procrastinate on writing.

AN: Definitely plotting was the hardest part for me. In the world I built, time travel is mundane and has been going on for thousands of years. So everybody knows that history is constantly being edited, though there is some debate over how much and how difficult it is. Plus, it takes years to become a time traveler so it’s not like anybody can just jump into a Machine and muck things up. I kept finding myself having to explain how time travel works, including paradoxes and limitations and the Machines themselves—and that’s hard to do without boring infodumps. I still think there are some plotholes in the book. The fun part was researching the different periods my characters visit, like Chicago in 1893 and Petra in 13 BCE. I love research. It’s my favorite way to procrastinate on writing.

AW: So I’ll confess that I’ve been reading your book, and one of the things that’s really impressed me about it so far is that you aren’t shying away from the consequences of your conceit—you’ve clearly put a lot of thought into how this technology would have shaped the world and the perspectives of your characters. It’s a great illustration of what I see as the real key of building a good time travel story: coming up with a system that compliments the story you want to tell, that is interesting to learn about in the text instead of a chore, and that only breaks in ways that your readers don’t care about. Because the thing is, unless you’re writing a very specific kind of closed-loop-zero-free-will plot, basically all time travel stories are kind of bullshit if you think about them too hard; your time travel magic systems will break if you pull at them the right way. They key is to kind of narratively wave your arms around and yell such that your reader isn’t looking for that loose thread—ideally, they’re too caught up in your cool book to notice. (And to be fair, a version of this is true for nearly all works of fiction, it’s only that travel stories are especially vulnerable—so many moving parts, so much complicated causality!)

What are some of your favorite (or least favorite!) time travel stories?

AN: I’m a huge fan of the feminist time travel tradition, so I love all the classics like Octavia Butler’s Kindred, Joanna Russ’ The Female Man, and Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. Plus, modern masterpieces like Lauren Beukes’ The Shining Girls and Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe.

And there are so many more! I’m a huge fan of the bureaucratic time travel system that Kelly Robson invented for Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach. Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone’s This Is How You Lose the Time War was fascinating and I’m still mulling it over. And obviously, I freakin love Doctor Who. I even put a futuristic tool that’s basically a sonic screwdriver in my novel.

AW: See, this is great, because now I have a few new titles to put on my to-read list. As for me…well, on the books front, the classic go-to is Connie Willis for a reason, her Oxford stories are all so interesting. I was told to read them by my friend Gina Gagliano back when I first started working on Chronin in my mid-twenties—she was like, “People are going to assume that you were influenced by these books, so you should probably read them anyway.”

I’ll admit that, as a former film-student, movies are also a huge influence for me. The Back to the Future movies are classics for a reason, they hit all the major sub-genres of time travel stories and were definitely a huge influence on me as a kid. I absolutely adore The Edge of Tomorrow, which I think was bizarrely retitled “Live. Die. Repeat” at some point. It had all of the time-loop-story-competency-porn of Groundhog Day with bonus aliens and the terrifying badassery of Emily Blunt’s character, Rita. I also have a lot of respect for the film Primer as a tightly-written closed-loop story, but I wouldn’t say that I enjoy it exactly—it’s like the vegetables of time travel movies for me.

I also really love some of the time travel Star Trek episodes. They’re just so much FUN. Star Trek is already so hand-wavey about its own science fiction to begin with, it’s a perfect tonal fit for “Don’t Worry About It” time travel nonsense. “Yesterday’s Enterprise” from TNG and “Children of Time” from DS9 are a couple of my favorites, they’re so deliciously melodramatic but also, have some genuinely wonderful character moments and compelling moral dilemmas.

If you could time travel to any period when would you go to?

AN: I want to visit Cahokia, an indigenous city near today’s East St. Louis, which was the biggest city in North America in the 1000s. Its people built massive city grids, huge earthen pyramids, and had a very cosmopolitan social life. But we don’t know very much about them, and they left no writing behind. I just want to visit the city on an ordinary day and say hi to everybody (assuming my time machine helps me speak a proto-Siouan language). And also ask them ALL THE QUESTIONS ABOUT EVERYTHING.

AW: Oh, that sounds fantastic. I mean, the past is always unknowable, but some things have been more thoroughly lost to us than others. My first thought when I saw this question was that I’d love to visit a Neanderthal community, and see what their lives were like. My second thought was embarrassingly Basic but…listen, I wanna see some dinosaurs, okay? I never really left that phase behind me. And if the future is an option? I’d be desperate to travel forward to when we discover some evidence of life on a planet other than Earth. In my heart, I’m kin with Eleanor Arroway.

Both of your books also feature LGBTQ+ characters—was that a conscious decision, or always a part of how you approached the stories?

AN: I think we all know that time travel is very gay. I mean, that’s just a fact. As evidence, I will cite David Gerrold’s classic early 1970s novel The Man Who Folded Himself, about a guy who time travels so much that he meets dozens of versions of himself and they buy a giant mansion together and have gay orgies.

I think we all know that time travel is very gay

Also, the whole Doctor Who/Captain Jack situation is another piece of evidence. And various subplots on Legends of Tomorrow. Plus, as Amal El-Mohtar pointed out in a recent article, this year alone there were like four new novels with time-traveling lesbians. It’s gays all the way down.

AW: Yep yes enthusiastically seconded, this here is a thoroughly queer genre. If anything, Chronin is a testament to this fact — I started working on it over a decade ago, when I was still telling myself how very straight I was (spoiler: I was incorrect). There’s a secondary pairing in the book which I always intended to be gay, but at the time I had no self-awareness whatsoever that I was writing a deeply queer story that was full of queer characters. That realization came more than halfway through the process of drawing it, and involved a pretty major revision of the second book in order to be more deliberate and effective with what I was doing. It all was much more closely tied to my own experience than I’d realized, and my own experience turned out to be a deeply gay one.

Did you see any particular challenges or benefits to adding LGBTQ+ characters to stories that deal with different historical periods?

AN: My main goal in this novel was to center groups who are traditionally ignored in time travel stories. So for example, the pivotal historical events that change the timeline in my novel involve women’s reproductive rights and universal suffrage. When women get the vote at the same time as freed slaves in 1870, Harriet Tubman becomes a senator and changes the course of history. But as a result, there’s a stronger anti-feminist backlash in the 20th century, which results in abortion never being legalized. There’s a trope in time travel stories now about how people of color and queer people have a hard time going back into history, but my point is that there have always been pockets of resistance and tolerance, and we do have a place in history if you just look.

AW: It’s easy to forget how aggressively curated the history that’s taught to us in schools and by pop culture tends to be — as a white American from the Boston area, I had a very specific version of the world presented to me that centered a white, straight, colonial perspective and often erased or mischaracterized everyone else. There have always been queer people, and the homophobia that’s caused so much damage for, say, the people in my own circle, is a relatively recent invention that was then forced onto other cultures and communities. The cast of my book is a mix of time travelers from the future and natives to the past, and I didn’t want to present queerness as a modern invention — my book is set in Japan, during a period when romantic attachments between men were very common.

What are some of your favorite science fiction approaches to LGBTQ+ identities and issues?

AN: I’m not too picky. I like it when a story with an ensemble cast assumes that there will be queer characters and romances. Basically, give me some gay love stories and hot smooches and I’m happy. Throw in some human-alien romance, or human-monster romance and I’m even happier.

AW: Same Gay Hat. Also, while I both understand and accept and support other people’s desire to explore queer trauma through fiction, I personally prefer to write and read stories where my characters’ problems are unrelated to their queerness. Which doesn’t mean that I want only sanitized, frictionless narratives, just that I want the friction to be coming from someplace else. I deeply, deeply love Anne Leckie’s novels, in which everyone is gay and awful things are constantly happening. Those awful things are just, you know… “My best friend’s dad was murdered and he isn’t taking it well” or “I used to be a space ship and now I’m not and it feels really weird.”

What is your dream project – what would you like to tackle but haven’t had the time or opportunity?

AN: I really want to write a non-fiction book about social behavior and communication in non-human animals, maybe ants or crows or cats. Or all three! Octopuses and whales are interesting to me too. I’m a science journalist and I try to keep up with the latest research on animal communication. At some point, I’d like to spend a field season with scientists who are spending time among the animals they study, listening to them and observing. I’m so sick of hearing humans talk about themselves; it would be nice to spend a few weeks listening to what other species have to say.

AW: I’ve had some short fiction published over the years, but for the most part my professional work has been All Comics All The Time. This is the most cliche possible sentiment, but I’m trying hard to make space in my life for writing a prose novel—I have a story about lesbian wizard podcasters that’s been rattling around in the back of my head for a while, and I think it’ll be a lot of fun to write once I have the momentum going. I adore comics, don’t get me wrong—I edit them as well as writing and drawing them, I made a podcast about the graphic novel industry, like I have leaned all the way in—but the medium is better suited to certain kinds of stories and ways of telling them. I’ve been saying “This is the year I will Do A Novel” for basically a decade, but….okay THIS TIME I mean it.

opens in a new windowThe Witness for the Dead is hitting shelves on 06/22 and to celebrate, we’re doing a throwback to this amazing Rules vs. Guidelines in Fantasy guest post from author Katherine Addison! Check it out below.

opens in a new windowThe Witness for the Dead is hitting shelves on 06/22 and to celebrate, we’re doing a throwback to this amazing Rules vs. Guidelines in Fantasy guest post from author Katherine Addison! Check it out below. opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

It’s a mechanism that keeps sneaking up on me honestly—I’ll start out building a story about some other thing entirely, and then whoops, turns out that time travel is once again necessary to make the machinery of the story work. Different systems, different genres, radically different plots, but I just can’t seem to resist hurtling my characters around through time. That said, I do think there are some core themes that knit all these stories together, themes which I’m clearly interested in — most time travel stories are about exploration, or regret, or control. Chronin has a little bit of all three — the mechanism is a time travel program used by academics, and the antagonists are either picking at the scabs of the past or desperately trying to reshape the future.

It’s a mechanism that keeps sneaking up on me honestly—I’ll start out building a story about some other thing entirely, and then whoops, turns out that time travel is once again necessary to make the machinery of the story work. Different systems, different genres, radically different plots, but I just can’t seem to resist hurtling my characters around through time. That said, I do think there are some core themes that knit all these stories together, themes which I’m clearly interested in — most time travel stories are about exploration, or regret, or control. Chronin has a little bit of all three — the mechanism is a time travel program used by academics, and the antagonists are either picking at the scabs of the past or desperately trying to reshape the future. AN: Definitely plotting was the hardest part for me. In the world I built, time travel is mundane and has been going on for thousands of years. So everybody knows that history is constantly being edited, though there is some debate over how much and how difficult it is. Plus, it takes years to become a time traveler so it’s not like anybody can just jump into a Machine and muck things up. I kept finding myself having to explain how time travel works, including paradoxes and limitations and the Machines themselves—and that’s hard to do without boring infodumps. I still think there are some plotholes in the book. The fun part was researching the different periods my characters visit, like Chicago in 1893 and Petra in 13 BCE. I love research. It’s my favorite way to procrastinate on writing.

AN: Definitely plotting was the hardest part for me. In the world I built, time travel is mundane and has been going on for thousands of years. So everybody knows that history is constantly being edited, though there is some debate over how much and how difficult it is. Plus, it takes years to become a time traveler so it’s not like anybody can just jump into a Machine and muck things up. I kept finding myself having to explain how time travel works, including paradoxes and limitations and the Machines themselves—and that’s hard to do without boring infodumps. I still think there are some plotholes in the book. The fun part was researching the different periods my characters visit, like Chicago in 1893 and Petra in 13 BCE. I love research. It’s my favorite way to procrastinate on writing.