opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

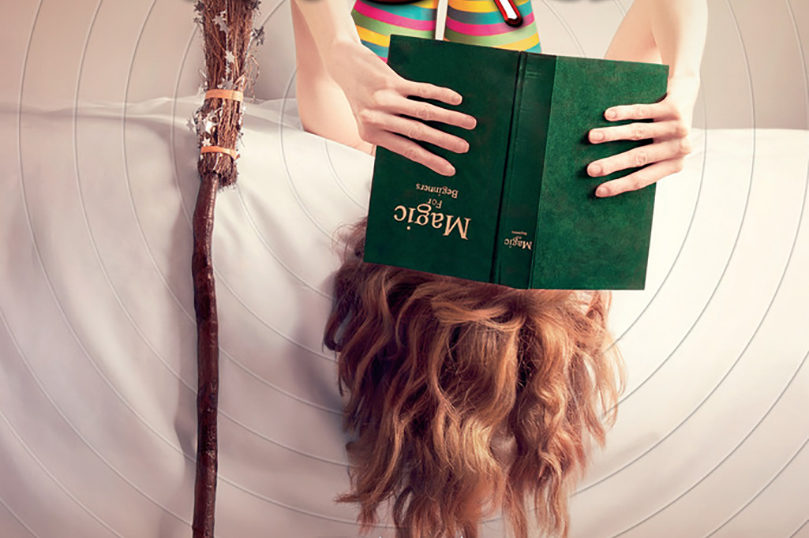

opens in a new window Welcome back to opens in a new windowFantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from opens in a new windowSeriously Wicked by Tina Connolly, about a reluctant young witch named Camellia whose mother is – well – seriously wicked. Cam’s adventures continue in opens in a new windowSeriously Shifted, available now, and opens in a new windowSeriously Hexed, available November 14th.

Welcome back to opens in a new windowFantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from opens in a new windowSeriously Wicked by Tina Connolly, about a reluctant young witch named Camellia whose mother is – well – seriously wicked. Cam’s adventures continue in opens in a new windowSeriously Shifted, available now, and opens in a new windowSeriously Hexed, available November 14th.

Camellia’s adopted mother wants Cam to grow up to be just like her. Problem is, Mom’s a seriously wicked witch.

Savvy Cam has tons of practice thwarting the witch’s crazy schemes. But when the witch summons a demon to control the city, he gets loose—and into the cute new boy in Tenth Grade. Now Cam’s determined to stop the demon before he destroys the new boy’s soul. Which means she might have to try a spell of her own. But if she’s willing to work spells like the witch. . .will it mean she’s wicked too? With the demon squashing pixies, girls becoming zombies, and the school one spell away from exploding in phoenix flame, Cam has to realize that wicked doesn’t lie in your abilities, but in your choices.

1

True Witchery

I was mucking out the dragon’s garage when the witch’s text popped up on my phone.

BRING ME A BIRD

“Ugh,” I said to Moonfire. “What is—I can’t even … Ugh.” I shoved the phone in my jeans and went back to my broom. The witch’s ring tone cackled in my pocket as I swept.

Moonfire looked longingly at the scrub brush as I finished. “Just a few skritches,” I told her. “You know what the witch is like.” I grabbed the old yellow bristle brush and rubbed her scaly blue back. My phone cackled insistently and I pulled it out again.

HANG SNAKESKINS OUT TO DRY

FEED AND WALK WEREWOLF PUP

MUCK OUT DRAGON’S QUARTERS

DEFROST SHEEP

Done all those, I texted back. Been up since 5AM. Out loud I added, “Get with the program,” but I did not text that.

The phone cackled back immediately.

DONT BE SNARKY

THESE ARE CHORES BY WHICH ONE MUST UNDERSTAND TRUE WITCHERY

NOW BRING ME A BIRD

“Sorry, Moonfire,” I said. “The witch is in a mood.” At least she hadn’t asked me about the spell I was supposed to be learning. I stowed the brush on a shelf and hurried out the detached RV garage and back into the house. Thirteen minutes to get to the bus stop, to get to school on time. I threw my backpack on as I crossed to the witch’s old wire birdcage sitting in the living room window. Our newly acquired goldfinch was hopping around inside. The witch had lured him in with thistle seeds. “C’mon, little guy,” I said, and carried the cage up the steps of the split-level to the witch’s bedroom.

The witch was sitting up in bed as I knocked and entered. Sarmine Scarabouche is sour and pointed and old. Nothing ever lives up to her expectations. She is always immaculate, with a perfect silver bob that doesn’t dare get out of place. Right now she was all in white. The bed is white, too, and the sheets, and the walls—everything. She spritzes her whole room with unicorn hair sanitizer every morning so it stays spotless. It’s deranged.

“Put the bird on the table, Camellia,” she said. “Did you finish this morning’s worksheet?”

I plopped down on a white wicker stool, fished out three sheets of folded paper from my back pocket, and passed the top one to her. “The Dietary Habits of Baby Rocs—regurgitation, mostly.”

Her sharp eyes scanned the page. “Passable. And the Spell for Self-Defense? Have you made any progress?”

The question I had been dreading. I unfolded the second sheet from my pocket while the witch studied me.

Because here’s the thing: trying to learn spells is The Worst.

In the first place, spells look like the most insane math problems you’ve ever seen. Witches are notoriously paranoid, so every spell starts with a list of ingredients (some of which aren’t even used) and then has directions like this:

Step 1: Combine the 3rd and 4th ingredients at a 2:3 ratio so the amount is double the size of the ingredient that contains a human sensory organ.

In this case, the ingredient that contained a human sensory organ was pear. P-ear.

Har de har har.

That was the only part I’d managed to figure out, and I’ve been carrying around this study sheet for four months now.

The witch looks at these horrible things and just understands them, but then again, she’s a witch. Which brings me to reason two why I hate this.

I’m not a witch.

Maybe I have to live with her, but I’m never going to be like her. There was no way I could actually work this spell, so Sarmine’s trying to make me solve it was basically a new way to drive me nuts.

“Well, it’s progressing,” I said finally. “Say, what are you going to do with that bird? You aren’t going to hurt him, are you?”

The witch looked contemptuously down her sharp nose at me. “Of course not. This is merely another anti-arthritis spell, which will probably work just as well as the last forty-seven I’ve tried.” She drew out a tiny down feather from the white leather fanny pack she wore even in bed, clipped a paperclip on the end, and held it out to me. “Please place this feather in the cage.” She picked up her brushed-aluminum wand from the bedside table.

“Isn’t this a phoenix feather?” I asked as I obeyed. “I thought you couldn’t work magic on those.”

“But I can on a paperclip,” she said. She touched her wand to a pinch of cayenne pepper from her fanny pack, flicked it at the cage, and the paperclipped feather rose in the air. It stayed there, hovering.

I tried to remember what some long-ago study sheet had said about phoenix feathers. Very potent, I thought. Had a habit of doing something unexpected, like—

The feather burst into flame.

The goldfinch shot to the ceiling of the cage, startled.

“Watch out!” I said.

The paperclipped feather levitated and began chasing the finch. The finch cheeped and darted. The flaming feather maneuvered until it was chasing the bird in tight clockwise circles.

“You said you weren’t going to hurt it,” I shouted, moving toward the cage.

“Back away,” said the witch, leveling her wand at me. “I need sixty-three rotations of finch flight to work my spell.”

I knew what damage the wand could do. The witch was fond of casting punishments on me whenever I didn’t live up to her bizarre standards of True Witchery. Like once I refused to hold the neighbor’s cat so she could permanently mute its meow, and she turned me into fifteen hundred worms and made me compost the garden.

But the finch was frightened. A fluff of feather fell and was ashed by the fire. Another step toward the cage …

The witch pulled a pinch of something from her pack and dipped her wand in it. “Pins and needles,” she said.

“Pardon?”

“If at any time you start to disobey me today, random body parts will fall asleep.”

“Oh, really?” I said politely. “How will the spell know?” One foot sneaked closer to the cage, down where the witch couldn’t see.

“Trust me, it’ll know,” Sarmine said, and she flicked the wand at me, just as I took another step.

My foot went completely numb and I stumbled. “Gah!” I said, shaking it to get the blood flowing again. “Why are you so awf—?” I started to say, but then I saw her reach for her pouch and I instead finished, “er, so awesome at True Witchery? It’s really amazing. It’s taken me all this time to figure out just one ingredient in the self-defense spell.”

The wand lowered. Sarmine eyed me. “Which one did you figure out?”

“Pear.” I didn’t say it very confidently, but I said it.

She considered me. I thought a smile flickered over her angular face. But the next moment it was gone.

Still, she did not raise the wand again.

I breathed and shook my foot some more. I might get to school on time.

“Camellia,” she said, considering. Her manicured fingers tapped the white sheets as she studied me. Even in bed her silver chin-length bob was immaculately in place. “I am going to take over the city.”

“Really,” I said, with maybe too much sarcasm. I was still on edge about the poor finch, who was cheeping like a frightened metronome. But seriously, the witch was always coming up with new plans to take over the city. The last one involved placing a tank of sharks in the courthouse.

Her fingers tapped the wand but it did not lift toward me. She merely said, “Impertinence. Turn off your selective listening and hear me out. It’s time we witches reclaimed the world and came out of hiding at last. I have the most magnificent plan yet to control the city. But first, I need a demon.”

“A demon?” That was serious. “Don’t you think you should go back to sharks?”

“A demon,” said the witch firmly. “I shall put his spirit into the plastic mannequin in the basement. The scheme is perfect. I’m summoning him this very afternoon, so I need you to bring me two ounces of goat’s blood to lock him into the mannequin.”

She eyed me like I was going to complain about where to find goat’s blood, but goat’s blood is sooo old news. I’ve got a supplier. I was more concerned about this demon nonsense. “Anything else?” I said. The pins-and-needles feeling was finally wearing off and I could stand on two feet again.

“Three fresh roses, a dried pig’s ear, and two spears of rhubarb. Recite for me the properties of rhubarb, please.”

Um. That was just on a study sheet a week ago. “Used for stiffening, sharpening, etching. So frequently used in blinding spells that it was once declared contraband by the Geneva Coven. Also good in pies,” I said.

A fractional nod that meant approval. “And goat’s blood?”

Hells. “Also good in pies?” I said.

An odd line of disappointment crossed her brow. “Camellia, you really have to learn this,” she said. “All witches must be able to protect themselves.”

I gritted my teeth against this ridiculous statement. No matter how often I reminded her I was never going to be a witch, it didn’t make a dent. I was not going to waste another morning arguing. Especially not when the third sheet of paper in my pocket was my study sheet for today’s algebra test, and I had had zero time to study it due to snakeskin-hanging and sheep-defrosting and everything else.

The witch took out two crisp twenties from her fanny pack and handed them to me. “Very well, you may go.”

I took one step to the door, then turned. “Do you promise you’ll release the finch as soon as he’s flown far enough?”

A flicker of the eyelid that was the equivalent of a major eye-roll. “Yes, Camellia. What use would I have for a goldfinch? It would have to be fed, and it wouldn’t provide me with anything useful, like dragon tears or werewolf hairs.”

“Or free labor,” I muttered under my breath as I left the room.

I hurried out the front door and down the street toward the city bus stop. I’m usually the only one catching this particular bus, but today I noticed a boy in blue jeans standing there, scribbling in a notebook.

I slowed to a walk, trying to remember what I had read about demons. A tank of rabid sharks was one thing, but real demons were a nightmare. I knew that from the WitchNet.

You wouldn’t think it, but witches were very early adopters of the Internet. Like I mean by 1990, every single one of them was on, so there’s a huge network of information with everyone putting up their How I Made Some Dude Fall in Love With Me spells and so on. It’s not the same as the regular Internet, though. Witches are paranoid, and so just like their spellbooks, their sites have warding spells, attack spells, spell programs that change the spell recipe to be wrong if the site decides not to share with you—fun things like that. Digging for information on sensitive topics can be dangerous if you get far off the beaten path.

The witch won’t get me a normal-person cell phone—mine only connects to other witches and the WitchNet so I can learn more about True Witchery, blah blah. I would have to spend some time looking up demons today to figure out how to stop the witch this time. It seemed like I’d read something on Witchipedia about demon-stopping once.… All I could remember about demons was that, A) they were fire elementals, and B) they didn’t like being fire elementals. Their entire goal in life was to take over a human and warp them to their wicked will so they could stay on earth, and yes, I learned all that from the witch’s favorite show about demon hunters.

The boy at the bus stop did not look up as I approached. I still didn’t recognize him—perhaps he was a junior or senior I’d somehow missed. He had earbuds in and was muttering something, then scribbling furiously. It sounded vaguely like “cool stick of butter,” which seemed unlikely, unless he was trying to remember his grocery list. I got all the way to the stop before he glanced up—and right through me. He hummed as he looked back down.

I’m not super-vain, but I have to admit I felt a little miffed at that. I mean, he was tall and all—probably taller than me, which was nice, and somewhat rare. And okay, he was cute. But he wasn’t my kind of cute. He looked like he belonged in a boy band, with floppy blond hair and a sweet face. I like them dark and brooding, like Zolak the demon hunter, who wears leather pants with zippers all over them.

The bus was coming up the street. If I pulled out my algebra study sheet, I could get ten minutes of cramming in on the bus.

And then I saw a small yellow thing zip down the sidewalk and go right past my head. The finch.

Behind it was the flaming feather.

The witch had let the finch go, as promised. But she hadn’t bothered to catch the feather.

The finch zoomed around us, going right past the boy-band-boy’s face, and the boy even looked up at that. He pulled out his earbuds, searching for the dive-bombing bird.

I had to catch that feather. The bird streaked past us again, diving and dodging. I swung and missed.

“Is that your pet bird?” he said. “Can I help you catch it?

“Not exactly,” I said, grabbing at the feather again.

“What—wait, is there something chasing it?”

I lunged again, and this time I caught the feather. Turning so my back was to the boy, I blew on the feather until the flame went out. Smother it, I thought, and shoved it into my back pocket. I whirled around to find the boy looking at me with a puzzled expression.

“That looked like a flaming feather,” he said.

“No, it wasn’t,” I said. “It was a bumblebee. I didn’t want it to sting the bird. I’m against that sort of thing.” When you’re enslaved to a wicked witch, you end up thinking fast to keep all the weird witchy things a secret. Not always good fast, but fast. “Look, isn’t that our bus?”

I hurried past the blond boy to where Oliver the bus driver was opening the door for us. Oliver waved at me as I put my foot on the stair. He’s a good guy. He waits for me if he sees me running, and I bring him the witch’s secret windshield-washing formula when it’s sleeting. (Vinegar with three drops of dragon milk; he always says it’s just like magic, but he doesn’t know the half of it.) I like Oliver, and also I feel you should be extra-pleasant to someone if you plan to bring goat’s blood and turtle shells and live roosters onto their nice bus.

“Hi, Oliver,” I said, waving back.

“Behind you, Cam,” he said. “I think that boy’s trying to get your attention.”

I turned around to find the boy-band boy making wild fanning gestures at my rear end. “Excuse me?” And then I realized that my butt was really quite warm. A thin trail of smoke was coming from my back pocket.

The feather.

Oh hells. I fanned my rear end desperately, but the smoke only thickened.

“Sorry about this,” the boy-band boy muttered. He uncapped his water bottle and doused the rear of my jeans. Water soaked me down to my ankles. I gasped.

He looked both hopeful and apologetic, the same expression Wulfie the werewolf cub gets when he tries to bring in the newspaper and chews it to bits.

It is not often that my wits completely desert me, but they did then. There is no appropriate thing to say to someone who has just emptied his water bottle on your rear end to save you from going up in magical flames. Well, “thank you,” I suppose. A very squeaky sort of “thank you” came out as I tottered past the wide-eyed gaze of Oliver and sat down on the next-to-last seat left on the bus. Humiliation and anger at the witch warred inside me. How could I keep people from finding out about my weird home life if the witch insisted on sending flying flaming feathers to my bus stop?

Unfortunately, the very last seat on the bus was right next to me. That’s where boy-band boy sat. He looked down at me cautiously, like he wasn’t sure if I was pleased or upset with him.

Inanely I said, “Very hot bumblebees they have this time of year. Liable to burst into flame at any moment.”

He looked at me, and I honestly could not tell if he was as stumped for words as I was, or if he just thought I was the craziest person he had ever met. I mean, really, what do you say to that?

Slowly, he reached up and put his earbuds in.

Embarrassment flooded me and I stared out the window all the way to school. I didn’t even remember to look at my soaking-wet study sheet for algebra.

Jenah found me in the girls’ locker room, drying my butt under a hand dryer and flipping like crazy through my algebra textbook with the other hand. “Oh, honey,” she said, beelining to me. Jenah is my best friend and lockermate, and she would be my confidante if I dared have one of those. She’s tiny and trim and Chinese, third-generation. Her parents fancy themselves rebellious punk-rocker types, and they encourage her to express herself, whether that means changing the colored streaks she clips into her hair or obsessing about the auras she claims to see around everybody. She says the auras help her tune into the universe—sure, whatever. When you’ve got a dragon in your garage, you’re in no position to judge.

Today Jenah was all in black and pink and bracelets, and her black asymmetric partlyshaved bob-thing had a clipped-in pink streak. She is so chic, so herself, it hurts. My hair is kind of nutmeg, my eyes are kind of blue, my nose is kind of shapeless. Whereas Jenah looks like the epitome of Jenah, someone so perfectly who she is that she’s untouchable. One of those girls whom everybody already knows, even if we’re only in tenth. Jenah would never end up with crispy jeans, witch or no. She commandeered a mini–hair dryer from a freshman on the swim team and turned up the heat on my butt.

“Back to your blush brush,” she ordered the freshman. “I’ve got news,” she said to me, over the dryer.

“Well? Spill.”

“You know I can’t do that to our auras,” said Jenah. “The harmonic bridge that links us would be out of equilibrium if you acquired knowledge and I didn’t. We can’t risk that happening to our best friendship.” She flicked back her pink lock of hair. “What color is Aunt Sarmine’s bedspread?”

Seven years of best friendship and Jenah had never once seen the inside of my house or met the witch. I told everyone I lived with my aunt, because it was easier than explaining the truth about how the witch tricked me out of my loving parents’ arms before I was even born. Once when I was eight I looked up all the Hendrixes in the phone book (there were four) and spent the next month of Saturdays taking the bus to each house to ask politely if a witch had stolen a daughter from them—an adorable baby girl with nutmeg hair and a smudge of a nose.

Three of them laughed and one sicced his Chihuahua on me.

Anyway, it was one of Jenah’s goals in life to see inside my house and meet Aunt Sarmine. I told her she needed better goals, but she went on about keeping our friendship aura tuned by understanding my living space. Or something.

“Her bedspread is white with embroidered golden bumblebees,” I said. That was true. For a megalomaniac witch who made spells with goat’s blood, Sarmine could be pretty particular. “Now spill.”

Jenah clicked off the hair dryer. “Here you go, frosh,” she said, and tossed it back to the ninth grader, who dropped her blush brush to the dingy tiles with a clatter. “New boy in our grade,” Jenah said to me. “Quiet. Has potential. I think you could nab him if you move fast.”

“Not interested,” I said. “Too busy. I’m over the whole boy thing. I only date college men. I only date hot-dog vendors. I only date aliens from Neptune.” Jenah laughed appreciatively.

The freshman girl peered dubiously at her dirty blush brush. If I could casually walk her way, I could put some sanitizer on it. (Russian vodka with one unicorn hair steeped in it; the best cleanser of all time.)

I shouldered my backpack and palmed the small vial from the side pocket. One drop, on my finger. “Do you know if Kelvin’s back from his bout with the pig flu?” Kelvin was a total 4-H nerd—and an excellent goat’s blood supplier. I flicked the drop at the ninth grade girl and watched the air around her shimmer. That sink would be the cleanest thing in school for a week.

“Ew, I do not keep tabs on mustard-aura Kelvin,” said Jenah.

“You have him in drama! He gets up and recites monologues about milking cows or whatever. How can you not know?”

“Mustard-aura,” repeated Jenah. We left the shimmery-clean girl and sink, and strolled down the hall to First Hour Algebra II. Except we were running late, so it was a fast stroll. School had been back in session long enough for the walls to be well papered—fliers for clubs, posters for some school play, and the ubiquitous school-spirit banners in our stunning colors of orange and forest green. Outside the algebra room, a flier for Blogging Club was papered over with one for Vlogging Club, and over that, one for the Halloween Dance. “So you’ll be okay with going solo to that on Friday?” said Jenah.

“Yuck,” I said. “Why do we have a Halloween dance anyway? Who wants to celebrate that?”

“Halloween is super-important,” said Jenah. She flicked back her hair as we neared the classroom. “It’s a time when you can commune with spirits. Ghosts. Demons.”

I shuddered. “You wouldn’t be so fond of demons if you thought they actually existed,” I said. “Just like it’s real easy to think witches are cool if you haven’t actually met them.”

“Witches?” she said, with an eyebrow.

“Or whatever. You know.”

I pushed open the scarred wooden door and Jenah hissed behind me, “There he is. Go get him, tiger!”

’Course, you all know what happened next.

Sitting in the desk next to mine was a sweet-faced boy-band boy who, at the sight of me and my dry jeans, blushed red-hot pink to the tips of his perfectly shaped ears.

2

In a Pig’s Ear

It wasn’t the fault of the red-eared boy-band boy sitting next to me during Algebra II. I flunked the algebra test all on my own merits.

Okay, maybe I didn’t flunk, but there’s no way I did better than a 70, which was practically as bad. As long as I maintained my A’s, teachers didn’t get too upset when the witch didn’t come in for parent conferences. But a C-minus? If I went downhill in algebra, then good old Rourke would be calling Sarmine Scarabouche on the phone, and wouldn’t that just go over well. The witch had never come to a single thing at school my entire life and I planned to make sure it stayed that way.

The others streamed out the door as I pushed my way to Rourke’s desk in the back corner. “Mr. Rourke?” I said. He wore way-too-thin button-down shirts that’d been washed too many times. Jenah called him Mr. Visible Undershirt, sometimes too loudly.

“What is it, Camellia?”

“Mr. Rourke,” I said again. Here’s where Jenah would study his aura and see how to butter him up, but for good or bad, I was a straight shooter. “I know I sucked on that test. Can I do some extra credit to make up?”

“I don’t give out extra credit willy-nilly,” said Rourke, nudging the tests into a perfect stack. His four red pens were horizontal at the top of his laminated desk. A full two-liter of off-brand root beer stood capped on the corner, and an empty one fizzed off a faint sarsaparilla smell from the plastic wastebasket. I thought he must be lonely.

“Okay, what else could I do?” I said. “Could I study more and retake it? I know I’m not hopeless at math. I had A’s in Algebra One and Geometry. Algebra Two is just kinda … mysterious.”

Rourke scratched his whiskery chin. “You could come after school and work with our tutor. If I see improvement, I might consider some extra credit.”

“Awesome,” I said. “I’ll be in tomorrow.”

“Today,” said Rourke. “He only comes on Tuesdays and Thursdays.”

“I can’t today,” I said.

Rourke flipped through the tests till he found mine. Without even needing an answer sheet, he went through, x-ing out my work with a thick red felt tip.

“Er. I thought we got credit for showing our work?”

Rourke drew another set of red X’s. “If it’s good work,” he said. He flipped back to the front, capped his first red pen and chose a different one from the lineup. This one was a lurid red-orange and smelled like rubbing alcohol. In slow motion it wrote a very decisive “61%” next to my name. “You know, I have been looking forward to meeting your aunt,” Rourke said. “I hear she is a very striking woman.”

Cold dread iced my spine. “I’ll see you after school,” I said.

With Mr. Visible Undershirt commandeering my after-school hour, I was going to have to sneak out at lunch to get the witch’s errands done.

That is, if I should do her errands.

I spent all of Second Hour French considering that conundrum. Usually when the witch ordered items, I jumped. For example, once I failed to find elf toenails for her (I still haven’t found anybody who supplies them, for that matter. The witch refuses to admit that certain ingredients might be mythical.) For punishment the witch turned me into a solar panel salesman and made me go around to every house in a half-mile radius and lecture about alternative forms of energy.

Now I considered my foot. Losing one foot for a few moments this morning wasn’t the end of the world. I had stumbled, but I was still here. But what was going to come after that? Both legs? My body? My heart? I shuddered.

Despite what the witch had said, I didn’t think her spell could read my thoughts. It definitely knew when I acted against her—the step toward the birdcage had proved that. But thinking?

I clenched my fist and thought hard, I am not going to help the witch summon a demon.

Nothing happened. Well, there were some pins and needles in my fist, but only because I was clenching it so hard. Slowly I relaxed.

Okay, then. A plan blossomed. I would gather her ingredients, and then, at the very last possible second, I would destroy them. As long as I didn’t chicken out.

My phone vibrated in my backpack and I sneaked it out under cover of my desk.

PLANETS PERFECT @3:45

WILL SUMMON GREAT & NEFARIOUS ESTAHOTH >:-(

DON’T FORGET GOATS BLOOD

OR ELSE

Or else. Or else. I sighed. Everything falling asleep would still come, but later. The witch would come up with some worse punishment on top of that. Really, all I was doing was delaying my misery from right now until the end of the school day.

“Mademoiselle Hendrix? Comment dit-on dilemma en français?”

“Un dilemme,” I said. “Un dilemme.”

The school gave us an entire eighteen minutes to eat lunch, which was just enough time to get to one location: across the street to the specialty grocery, Celestial Foods. Which meant I couldn’t eat lunch with Jenah or track down Kelvin for the goat’s blood. I stuck a note on her half of the locker that said, “please please PLEASE find Kelvin during A Lunch and tell him I’ll pay double for two ounces of the usual, today, I owe you BIG TIME,” grabbed my emergency jar of peanut butter, and dashed down the hall to the side exit.

In theory it’s a closed campus, but in practice the security guys are always busy busting up smokers in the parking lot on the other side of the school, so as long as you’re subtle, you can sneak out the side door, through the overgrown elms.

I ate my peanut butter lunch while I headed to the store. It was a lovely October day, full of blue skies and red rustling maple leaves. My mind started to clear. I was going to get the witch’s ingredients, and then destroy them at the last possible second. Spill her tea on them—whoops! Explode them in the microwave. Something.

But that might not be enough to stop the witch.

Her taking-over-the-world plans tended to be pretty determined. I mean, surely the planets would align again tomorrow or Friday or something, right? She was theoretically capable of purchasing her own ingredients for the spell, even if I’d never seen her set foot in anything so common as a grocery store.

I needed to know how to stop the demon in case she got one summoned.

I pulled up Witchipedia on my phone. I had been about to look up demons this morning when I’d seen that new boy at my bus stop. My face got warm, thinking about it. I had been rude and awkward, and I did not like to think of myself as a rude, awkward person. I would find him and apologize. Maybe, too, I could ask him what he was listening to, and if the humming and scribbling meant he truly was a boy-band boy, because that would be kind of cool …

Ahem.

Demons. Witchipedia. Right.

I found:

Demon (disambiguation). Demon may refer to:

> Chad Demon, an embodied demon and WitchNet personality best known for a series of spoofs of American (nonwitch) TV shows

> Demons! The Musical, at three years, two months the longest-running witch show without the cast simultaneously exploding into paranoia and quitting

> Elemental obsessed with finding embodiment (aka a human soul and body to keep). Neutrality of this article is disputed.

It continued on from there, but I clicked on the “Elemental” article. A summoned demon had to have a living form to inhabit in order to spend time on earth. Once inside a body, demons became very tricky. Using a variety of techniques (see techniques), they could steal most humans’ souls in less than a week. A demon who obtained a soul could not be sent home, even when its contract was completed. It would keep the body for the rest of the body’s mortal life span. Witches untrained in demon summoning were advised to reconsider, as demons on the loose could cause chaos, plague, destruction, blah blah …

I bookmarked that section of the page to read later. Witches predicting terrible results tend to get wordy and melodramatic. The witch had said she was putting this demon in a mannequin, so I didn’t need to worry about demons eating souls.

I just needed to know how to stop the demon from fulfilling the witch’s latest city-taking-over plan.

The stoplight turned green just as I reached the crossing to the shopping center and I hurried across, skimming for the section on how to stop demons. Ah, here. The best way to stop a demon, it said, is—

And that’s when a tall girl burst out of nowhere, jostling my elbow and knocking my peanut butter to the sidewalk. I grabbed for it and my phone went flying. The plastic peanut butter jar cracked as it hit the curb. The phone hit the sidewalk and skittered across the cement.

The screen went blank. “Oh, hells!” I growled at it.

The girl whirled, clutching a paper bag. “Watch where you’re going.”

“Me? It was you! Oh. Sparkle.”

Sparkle was a junior, the sort that trailed even seniors in her wake. Half Japanese/half white, nearly as tall as me, and pretty even before the nose job. She was in a long shimmery skirt and beaded jersey top; as usual she looked too glamorous for school. It wasn’t a look any other girl could’ve carried off, though a few of her clueless followers tried, with predictably hilarious results.

“Camellia,” she said with equal distaste. “Didn’t grow into your nose over the summer, I see.”

“At least it’s my own nose,” I said.

Sparkle pounced on that, paranoia sharp in her voice. “I never—What have you heard?” Her fingers felt along her newly straightened nose. “Are people talking about it? It’s all lies. It just … happened.”

“Oh, please,” I said. “At least get a better cover story.” I picked up my broken peanut butter and cell phone. The display was scratched. I pressed the “power” button, hoping it would turn on without the coaxing of dragon milk.

Sparkle’s lips tightened and she clutched the coral cameo she always wore. “Do you still want to be a magic witchy-poo when you grow up?”

For the record, there’s nothing worse than having a dead friendship with the top girl in school. A girl who’s so top that if she wants to wear sequins and go by the name of Sparkle, girls go cross-eyed with jealousy and think it’s cool. We were best friends when I was five and she was six and I didn’t know better. I just remember a time when I thought she was the most awesome girl in the world and we spent every single second together.

Told each other all our secrets.

Sneaked down to the basement to watch the witch work a secret, nasty spell …

I shuddered at the memory. My stupid innocence back then meant this skinny, black-haired, glittery girl knew way too much.

Sparkle watched me cringe at her words. Her mouth softened, opened to say something.

“I think there’s an ant in my peanut butter,” I said.

Sparkle stopped whatever she’d been going to say. She looked down her straightened nose at me and the sneer returned. “Don’t let me keep you from your shopping, Cash.” My old nickname on her lips cut me to the quick.

“I won’t, Miss Smells-to-the-Left.” The childish insult rolled delightfully off my tongue.

As she stalked off I wondered exactly what she was doing over here. Her paper bag looked like it had Celestial Foods’ logo. I leapt to a range of improbable ideas, but then I shook my head. The only reason I was suspicious about other people’s doings was because I was always hiding things.

Normal people didn’t have to learn about the properties of rhubarb and where to source juniper berries and grapeseed oil.

Normal people got normal food at the grocery store.

I hurried into Celestial Foods, snagging three pinky-white roses from a galvanized watering can by the front door. They dripped on my shoe as I wound brown paper around their bottoms. First ingredient—check.

Next, the fresh produce section, where Alphonse, the son of the owner, was stacking pyramids of squash. Alphonse was a college boy, but not the kind of college boy that makes you wonder if you should pretend to know how to do a keg stand if suddenly called upon to demonstrate. (I mean, he’s cute and all, but he doesn’t leer, and I’ve never once heard him say “woooooooo.”) He had black dreads to his butt and vegan sandals and he was majoring in environmental engineering because Celeste thought that was a positive career path, but really he just wanted to be one of those people who sneaks into labs and sets all the rabbits and monkeys free.

“Heya, Cam,” he said. “What are you trying to track down this time?”

“A weird one today,” I said. “One pig’s ear.” The moment it came out of my mouth I remembered to whom I was talking and my stomach fell. A pig’s ear! Alphonse would never forgive me.

Except he nodded and said, “Good timing. We just got a batch in.” He hollered over his shoulder to the back of the store, “Hey, Mom, can you bring Cam a pig’s ear?” He turned back to me and my open mouth and said, “Right time of year for them. Anything else?”

“Well, um. Rhubarb?” I said. I wondered how you could have a wrong time of year for pig’s ears. I turned around, looking for where the rhubarb had been before. Except … it wasn’t. “Oh, man. Is rhubarb out of season now?”

“Trying to stick to locally grown, when we can,” said Alphonse. “Flying out-of-season veg around the world is just not good for—”

“I know, I know,” I said. Alphonse took everything so personally. “I’m not criticizing. My aunt needs some.”

He dragged me down the crammed produce aisle, and I nearly took out a pyramid of spotted apples with my hip. “We have some really nice local pears in. If she’s making a pie—”

“Not a pie. She really just wants some rhubarb. Sorry.”

“She should’ve come in September. That was the last of it,” he said.

“I got some in September,” I said. I tapped an acorn squash thoughtfully. “Does it come any other way?”

“Frozen,” he said.

“Yes?”

“But we don’t carry that anymore. Our last supplier was caught doing business with people who do business with people who don’t compost.”

“Did you say your mom was here?” I said.

“Oh, I just remembered we have it canned.”

“Thank you.” I took the can from Alphonse and trailed him up to the register. I had seven minutes left and it only took six to walk back to school. “How’s the eco-work?” I whispered. “Eco-work” for Alphonse covered everything from protesting fracking to sneaking into people’s homes to turn off their lights. As long as there was a potentially dangerous situation involved, he was in.

“Not good,” he whispered back. “We’re trying to liberate some lab animals at the campus, but we can’t get an inside man or woman on the job.” He considered. “Or a gender-neutral person. Or multiplegendered. I wouldn’t want you to think I was being exclusionary.”

“I didn’t think that,” I assured him. “I’m in complete agreement with liberating testing animals. Um, speaking of, do you think your mom was able to find the pig’s ear?”

Alphonse moved spaghettied piles of register tape and recycled paper bags as he squeezed behind the register. “Hey, Mom!” he shouted.

Celeste hurried down the cereal aisle, wooden necklaces clacking. Celeste is black and somewhat rounded, and unlike her son, has just a hint of some sort of British in her voice, even though she’s lived here since she was like twelve. I’d come to associate Brits with extreme helpfulness and a listening ear over the years, which will probably not be useful if I ever go to England. Celeste pushed her plastic glasses up her nose. “Alphonse, love, we have an intercom.”

“Uses electricity,” said Alphonse.

“Camellia, darling, it’s lovely to see you.” Celeste enveloped me in a warm, wool-cardigan hug. Then produced something from her apron pocket. “Here’s your pig’s ear.”

The “pig’s ear” was pinky-brown. It had a ruffled, twisty cap and a spongy stem with a bit of dirt on the bottom.

Oh. “Is that a mushroom?”

“Pig’s ear mushrooms,” she said. “Autumn only, get them while you can. Such a sweet name. I assure you, I’d rather sell mushrooms than real pig’s ears.” She set the mushroom on my rhubarb can.

“We wouldn’t sell real pig’s ears,” growled Alphonse as he rang me up. “Barbaric, mutilating…”

The worst part of that was, I realized then that I didn’t like the idea of a real pig’s ear either. I’d just been thinking of it as an item to keep the witch off my back and not something that once belonged to a real live animal.

You know how you grow up with something day after day and you’re so used to it that you don’t realize you don’t agree with it till all of a sudden?

Yeah.

I didn’t have the nerve to say I was supposed to find a real one, so I paid for the mushroom along with everything else.

“What is your aunt going to do with just one mushroom?” Celeste said.

“Um. Make One-Mushroom Soup?”

Celeste patted my shoulder. “Always good to see you, love. Bring your aunt in here sometime, will you? From the sound of her recipes over the years, I’ve always thought we must have a lot in common.”

“Right. Definitely. Any day now. Just as soon as she gets back from her trip to Nepal. And gets over the chicken pox. And her fear of grocery stores. And learns how to speak English. Very soon now,” I said, and flat-out ran back to Fourth Hour American History.

3

Goat’s Blood

American History I is the worst class to have after lunch, because if there’s anything I’m going to fall asleep over, it’s Mrs. Taylor’s teaching method of playing ancient VHS tapes where actors explain the Bill of Rights using hip slang. Not that I was going to fall asleep today. I drummed my fingers and worried over whether Kelvin would be able to bike all the way home to his farm and back with the goat’s blood in time for the great planetary alignment. Usually the witch gave me a couple days’ notice for the weirder stuff, and Kelvin and I did a cooler handoff. I drummed harder.

My worries were interrupted by the appearance of two notes. First was the best message. A knock on the door and a student brought me a terse printout from Rourke that said: Tutor sick. Come tomorrow.

I breathed a sigh of relief and immediately received a second note. This one was on purple paper and was passed across the aisle to me while a tall permed actor said, “Yo, you mean I don’t have to give these grody Redcoat soldiers room and board?” The note had been sent by Jenah to Dean to Kyndra (who hissed, “Get a phone!”), and it said:K says too weak from pig flu to bike. Ugh! Will phone his Mom to bring yr request at 3 PM. Meet under T-Bird. 2bl UGH.

The T-Bird was the gigantic metal Thunderbird statue, our mascot, perched at the old front entrance to the school. It was up on a big cement block, and its claws extended to grasp a tiny mouse sculpture hidden in the grass. Since the new addition a decade ago, the old statue had gotten overgrown with ivy and shrouded in elms, so the “double-ugh” was in reference to the Thunderbird’s reputation as a place for hookups. But I doubted Kelvin paid any attention to things like that, so the super-sexy implications of the T-Bird were not the thing that made my blood run cold.

It was the phoning of the mom.

And the asking her to bring goat’s blood.

Now, I didn’t know Kelvin’s mom up close and personal. But even though she lived on a farm, she was still a mom. What mom wouldn’t be weirded out by knowing that her son was marketing goat’s blood to some girl at school? Come to that, how did Kelvin have goat’s blood around, anyway? I’d never really wanted to know—and now, the more I thought about it, the more it bothered me, like the pig’s ear.

At three, I grabbed my stuff from my locker and headed for the Thunderbird statue. The shaded area around the T-Bird was full of boys macking on girls and vice versa. (Boys macking on boys hung out in the theater, and girls macking on girls met in the park.)

Kelvin is tall, white, and wide, and he stands all stifflike. Like a bowling pin. He was shifting from one foot to the other, carefully not looking at a couple sucking face in the ivy near his knees. His deadpan face was moon-pale in the green shadow of the elms. He held a red-and-white mini-cooler.

Behind him, Kelvin’s mom waved from the car. She was wide like Kelvin, sporting a baggy red T-shirt, frizzy blond-gray ringlets, and a smear of sunblock down her nose.

She did not look suspicious.

I relaxed and waved back. “Thanks, Kelvin. I owe you big-time.” I parked my butt on the concrete base of the T-Bird and pulled out the last of my cash. “I don’t have all I promised you but I’ll bring the rest tomorrow. You know I’m good for it.”

Kelvin took the folded bills and nodded. “Kel-vin is a-ware,” he said in the robot voice he used sometimes. He did a lot of things that clearly he found funny, even if nobody else thought so. I was used to it. He set the cooler down on the concrete with a skritch.

“Did your mom wonder what was up?” I said.

“I told her you needed it for important witch rituals,” said Kelvin, his wide face dead serious.

I nearly fell off the statue base. Then I reminded myself that was Kelvin’s sense of humor acting up again. Deadpan didn’t even begin to describe it.

“Ha ha,” I said. “What did you really say?”

“I told her you needed it for a science project,” he said. “Testing it to see what hormones showed up.” Robot voice. “Now she thinks you’re sma-art.”

Another joke, but this one I could handle. “Excellent news. I aim to fool everybody,” I joked back. Then I steeled my nerve and asked, “By the way … How do you, um, get the goat’s blood?”

“Fangs,” he said.

I raised eyebrows.

“A syringe, of course. Don’t worry, I told Mom your witch rituals needed it to be fresh.”

“You’re such a kidder,” I said weakly.

“Good trade. Robot Kelvin bring you blood, you go to Halloween Dance with him. Together, dance like robots.” He improvised a few steps.

Which kind of looked like fun, but my thoughts were elsewhere, jumping ahead to catching the bus with my treasure trove of ingredients. “Smart and easily bought by goat’s blood,” I said. “My reputation is improving every second I stand here.” I jumped to the ground, narrowly missing some dude’s hand. “Look, I gotta run or I’ll miss my bus. But thanks again.” I punched his shoulder in a friendly fashion and hurried through clinging couples.

The bus was already loading, so I ran the last twenty feet, cooler banging. The door stayed open and I swung aboard just as it pulled off.

Despite the sweaty-boys-on-bus stink, I breathed a little easier. I had everything but the pig’s ear, and my only homework I hadn’t finished in class was reading the first two acts of something called The Crucible. I could get that done after my evening chores. Maybe I’d read it to Moonfire during her dinner. She liked being read to, even though I was never sure how much was lost in translation.

The bus was packed, as usual, but there was one seat left.

A seat saved by a backpack belonging to a tall boy with floppy blond hair.

“I saw you running, and I thought I owed you one for soaking you this morning.” He grinned and a teasing expression crossed his kind face. “I almost had to fight that football player for you, so say you forgive me.”

“Of course I do,” I said, and wondered if it was my turn to have pink ears. After all, it’s not every day a boy says he’s willing to fight a football player to secure you a bus seat, even if it’s just a joke. “And—forgive me, too. I was rude, and I’m sorry.” I started to sit down in the space he made, then stopped. “I’m not on fire again, am I?”

His eyes flickered down to my jeans and back up. “All clear.”

I plopped my backpack and rose bouquet on my lap and set the mini-cooler between my feet, where I could keep track of its whereabouts. The orange and yellow trees whisked by outside as the bus lurched toward home. I was going to make it.

Except … the pig’s ear.

The pig’s ear that I didn’t want. The pig’s ear that I had to get … or else.

I sighed.

“What’s up?”

“I had a shopping list of stuff my aunt needed today … never mind.” I drummed my fingers on my jeans, thoughts churning over what to do. If I didn’t bring the witch all the ingredients, there would be punishments … but I couldn’t let her summon the demon … “Gah, I give up,” I said. “I’m just not going to get the last thing. I’m not.”

My earlobe fell asleep. Then a whole patch of my head. I shook my head, trying to get feeling to return.

One thigh went out. A shin down to the ankle. Then all my toes snuffed out, pop pop pop—

“Gah, I mean I am going to get the stuff, I am,” I said, desperately drumming my feet on the bus floor until sensation returned. I snuck a glance at boy-band boy, who seemed tempted to put his earbuds in again. “Sorry. My aunt … is kind of demanding. She needs a lot of specific things for her … job.”

Boy-band boy lowered his earbuds and looked thoughtful. “Does she work for herself?”

“In a manner of speaking. Yeah.” I massaged my ear as the pins and needles died away.

He nodded. “My parents ran a no-kill animal shelter in my old town,” he said. “My dad ran the place and my mom donated time as a vet. I had to pitch in. You can’t blow things off like everyone else can, you know? Not if your parents have a family business. There are dogs to walk. Cats to rub with disgusting flea medicine. Cages to scrub after the cats have scraped all the flea medicine off.”

“Up at five every day?” I said.

“Rain or shine.”

“Study with one hand, muck out kennels with the other?”

“Sounds like you know the drill.”

“Why did you move here?”

He shrugged. “Couldn’t ever get enough donations. We finally had to transfer all the animals to the local county shelter and shut down. That was rough … well. Mom and Dad wanted a change, and Mom found a new clinic up here.” He wound down, looking a little embarrassed about having shared so much. But he had done it out of kindness, trying to empathize with his animal shelter story. It made me warm to him.

Maybe giving him one piece of information was worth the risk. “Do you know where I could get a pig’s ear?”

“Like for a dog?”

“Oh!” Why hadn’t I thought of that? “Yes,” I said.

“There’s a pet store in biking distance from our bus stop,” he said.

“Right!” I had gotten emergency dog food there once for Wulfie when the witch was in D.C. trying to transform the vice president into a grain elevator.

“But don’t bother. I got a whole bag for Bingo the other day after he ate my sneakers. I’ll give you one.” He cocked his head, the boy-band-boy hair flopping, and it suddenly made him look devilish instead of sweet. “It’s the least I can do for soaking you.”

Another nice gesture. I could get used to this. “I don’t even know you and already I dub you ‘The Best,’” I said. “My name’s Camellia, but my friends call me Cam.”

“Devon.”

“So, Devon. Are you in a band?”

He looked startled. “How did you know?”

“You were humming and writing in a notebook this morning,” I said. I didn’t mention the part about him looking like a boy-band boy. “Songs?”

His eyes lit up. “They just grab you when you’re walking along. Bits of melody, lyrics.” He ran his fingers through his hair. “I mean, they’re not all equally good…”

“Sing one?”

“On the bus?”

“Sure,” I said. “Don’t musicians like to show off?”

His ears went a little pink, but he closed his eyes and sang in a velvety sort of voice, “She’s a cool stick of butter with a warm warm heart…”

“So there was a stick of butter in it,” I said when he stopped.

“What?”

“Is that all there is to the song?”

“So far,” he said. “Dad always says the first phrase comes free, but then you have to work on the rest. I used to take my guitar to my old school and sit outside during lunch and work out chording.”

“I like it,” I said. “So what do you play in your boy band?”

“Regular band,” he said.

“Regular band. Backup vocals, some guitar?”

“They want me to sing lead but … er…” He trailed off. “Stage fright.”

“Ooh,” I said sympathetically. The bus stopped on my street and we got off, heading down the sidewalk toward the witch’s house. “Have you tried imagining the audience in their underwear?”

“Oddly enough, that doesn’t help.” He fiddled with his backpack. “During practice it’s great. I mean, we’re singing the stuff I wrote, right? It’s awesome. It’s a rush. And then we get to a concert … My voice shakes when I solo and that’s all you can hear on the mic. Embarrassing. We’re not even famous, you know? Have you heard of Blue Crush?”

I shook my head.

“See? I’m talking backyards, church concerts, talent shows. That’s what we’ve played. Maybe now that I’m an hour away I should let them find someone new, so they’re not stuck with me…” He tugged a lock of his floppy blond hair and trailed off. “Well, look. I’ll run home and get you that pig’s ear, okay? I’m just a block over.”

“You’re awesome,” I said. We stopped in front of my driveway. It’s surprising how normal the witch’s house looks from the outside: an ugly old split-level in browns and tans, landscaped with thorny bushes that she prunes with a ruler. I didn’t know what to say about the stage fright, so I just slugged his shoulder sympathetically. “Oh hey, I know this sounds weird, but don’t ring the doorbell, okay?” I made the crazy sign around my temple. “My aunt hates being interrupted. I’ll meet you in the driveway in, what, ten minutes?”

Devon nodded. “All right. See you soon, Camellia … Cam.”

I hummed to myself as I set the roses and cooler on the front porch and dug around for my keys. There was something pretty awesome about a boy singing a song to you, even just one line of a song. I had never particularly thought about boy-band boys before, but perhaps they were beginning to grow on me.

I unlocked the door and Wulfie came tearing out of the house, jumping on me and licking my face. “Down, boy,” I said, laughing. He tore off around the yard in joyful circles, going, “arf arf arf,” while I hummed. It really was a spectacular fall day. Had the sky ever been this blue? Surely it wasn’t just the chat with the boy-band boy making those fall leaves so glorious? I pulled out my phone to take a picture of happy Wulfie plowing through piles of red leaves, and the sight of the scratches all over the phone’s surface brought everything flooding right back. Sparkle. Witchipedia.

Demons.

I just needed to know the end of that sentence The best way to stop a demon is …

I hit the “power” button a whole bunch, but all that happened was the screen blinked greenly at me through its sidewalk scratches.

Stupid Sparkle.

Luckily, like I said, witches were big on the Internet. We had a kitchen laptop that Sarmine used for recipes, since she cooked dinner. I looked down at the werewolf pup, who was busy looking for a spot to do his business. “Don’t go anywhere,” I told him sternly, and ran inside. I thunked the laptop down on the yellow laminate counter and flipped it open. Pulled up Witchipedia. Demons, demons …

The witch swept into the kitchen, a wave of lavender and lemon cleaner billowing behind her. Hard to tell if that was cleaning or spells. “The planets are aligning gracefully,” Sarmine said. “Soon it will be time to summon Estahoth. Are you baking something?”

“Er,” I said. I scrolled down the page, scanning.

“Cooking is a waste of your precious time,” Sarmine said. “If you have extra time in the afternoons you should apply yourself to learning the spells I set you. A good self-defense spell is every witch’s best friend.”

This is the point where usually I say, “not a witch,” but I didn’t want to get sidetracked down that conversation. “Just curious about demons,” I said. “You never had me learn about them.”

“Camellia,” said the witch in her most aggrieved tone, “There are so many things that you have not learned about that we cannot possibly encompass them all in the short time I get with you each day. Now, if you would just apply yourself, or give up going to that useless human school—” She brushed a bit of lint off my shoulder, and I tweaked the laptop so she wouldn’t see what I was looking for.

“I love that school; you can’t stop me,” I said automatically. This was familiar territory and I’d just reached “The best way to stop a demon is …

“… not to summon it.”

Hells.

“Of course, today you will watch a most ingenious exhibition of demon summoning,” said the witch, sailing past me to close the open front door. “Perhaps that will finally be the magic to inspire you. This will be an excellent lesson for you to view. I expect this is the goat’s blood?”

The ingredients. I had to destroy the ingredients.

I lunged for the front door. We reached the cooler at the same time and she scooped it up.

“Repeat after me,” said the witch, cradling the cooler and rose bouquet as she returned to the kitchen. “Goat’s blood is used for binding, winding, and minding, in processes with tin, and as a substitute for Irish whiskey.”

“Um, what about the weather? Have you checked the forecast?”

“The forecast?” Sarmine peered out the kitchen window at the bright blue sky.

I lunged for the cooler, trying to tug it from her arms. “Giant thunderstorms predicted,” I panted, even as my ribs fell asleep and then my nose. “Electric interference. Everyone knows … don’t summon demons … in storms…”

She was strong, but I was younger and stronger. Her feet skidded, she staggered, her hands slipped off. I stumbled backward on the linoleum, clutching the cooler.

The witch’s silver eyebrows drew to a point.

She took a pinch of red powder and a spoonful of bread crumbs from one of the pockets of her fanny pack, spat on her hand, and touched her palm with her wand.

My mind raced, but this time there was no escape. My eyes were frozen, and clever words and maneuvers deserted me. I clutched that cooler tighter.

She flicked the wand at me and my hands turned into cooked noodles.

Seriously. Cooked noodles. Limp and soggy and rippled around the edges, like lasagna. Wobbly orange-painted fingernails marked their edges. My noodle hands slid right off the cooler handle and the cooler crashed to the linoleum floor.

I squeaked.

“A good self-defense spell would have been your best friend just now,” lectured the witch, picking up the cooler. Her heels clicked on the linoleum as she retrieved the fallen rose bouquet and set the roses carefully in a crystal vase full of water. “Why, I remember when I was eight, and a rogue wizard loosed the last orc on earth into our basement…” She patted her fanny pack. “But I had my ingredients and my wand! Oh, I was in top form.”

I lunged for the roses to destroy that possible ingredient instead, but my wobbly noodle hands missed the roses and smacked the crystal vase. The vase toppled over, rolling toward the floor. Self-preservation surged again. What would the witch do to me if I broke her crystal vase? Instinct made me launch my whole body underneath the vase as it fell.

Water soaked me for the second time that day. Rose thorns smacked my face.

But my body broke the vase’s fall. I lay on the cool linoleum floor, shaky, my limp noodle hands flopping back and forth.

“Impressive,” said the witch, as she grabbed the three roses between thumb and forefinger. Her skin was so dry and dessicated that the thorns didn’t even draw blood. “Did you remember the rhubarb?”

“Yes,” I said from the floor. It smelled like lemon cleaner.

“Very well.” Wand flick. “You may have your hands back.” The witch turned to the basement steps. “Oh, and Camellia? Bring the pig’s ear down with you. Nasty thing. I don’t want to touch it.”

Pig’s ear. Pig’s ear! Stupid witch and her stupid, stupid, evil things. I was so mad that I forgot all about the werewolf pup in the front yard, and my appointment to meet Devon in the driveway. I ran soaking wet after her and down the cement steps to the basement. “You can’t treat me like that!” I shouted. “I’m a person, too, you know!”

Sarmine raised a silver eyebrow.

“And pigs! You can’t treat pigs as things to just chop up for your stupid summoning. Pigs are living beings! They have rights, too!”

“Don’t drip on my pentagram.”

Angry as I was, I did step back at that. If the witch was going to summon a demon, I sure didn’t want him to escape his pentagram prison. I shoved my wet hair back and glared at the witch, who ignored me. Prickles went up and down my ribs as feeling returned.

The pentagram was a blue chalk outline on the cement floor. It was big enough for several people to stand inside. It had one of our banged-up card table chairs in it, and on the chair was the old mannequin on which the witch usually kept a pointy hat. The mannequin was wearing a faded red T-shirt that said, VOTE HEXAR/SCARABOUCHE 1982. It stared blankly at the wall, its body tilting to the left.

I felt a kinship with the mannequin. It didn’t have any idea what was about to be done to it. “I’m a person, too,” I muttered as I scratched my shins.

The witch knelt on the stone floor in her skirt and support hose and ruffled salmon blouse. “Isn’t my pentagram lovely?” she said reverently. “I haven’t drawn one in ages. Since before you were born.” She tapped it with her wand and blew on it gently, but the chalk dust did not budge.

“Why break a winning streak?” I said.

“Last time I summoned a very minor demon. Nikorzeth. He barely had enough power to heal the dragon’s broken wing.”

No wonder Moonfire kept one wing shuttered closed when the weather turned chill. Maybe if the witch would heat that damn garage for her … “Broken wing?”

“That’s when I found her,” the witch said absently. “She was at the end of a long flight and a storm moved in. She got tangled in a power line. And only another elemental can use magic on a dragon.” Sarmine’s eyes gleamed as she warmed to her lecture. Gods, that woman loves to lecture. “You know how powerful Moonfire’s milk is, and that’s just her milk. Why, the list of elementals is one of the first things I taught you. ‘Dragon, phoenix, and demon fell; these three a witch cannot bespell.’”

It was cool in the basement, in my damp shirt. I wrapped my arms around my waist. “Why do we call it milk?” I said. “She’s a reptile, not a mammal.”

“To be precise, she’s neither. Elementals are not part of the animal kingdom, as none of the three are mortals which feed on organic matter, as humans and elephants and werewolves do. Moonfire is of the class Draconis, which is another thing entirely,” said the witch. “But to answer your question more fully, I suppose we call her tear secretions milk because we always have.” Sarmine rocked back on her heels and studied her gold bracelet watch. “Three forty-one. We’d better get a move on.”

The witch crushed the petals from the three roses with a mini–food processor. She scraped the mixture into a porous stone bowl that usually holds bus tickets. Then she added one drop of dragon milk. The sweet scent of roses mingled with a fiery, coppery, dragony smell.

The witch walked around the pentagram three times widdershins and added a chiffonade of basil. Three times back and a pinch of dried salamander from her fanny pack. The salamander dissolved in a gunshot bang and shot up a purple cloud of smoke. My stomach was cold and knotted, and my wet hair hung in chill coils against my neck.

Watching the witch work a spell this dark and complex made me feel sick inside, and a long-ago memory of sneaking downstairs with Sparkle beat against my brain. I swallowed the memory, closed my mind against its darkness. Put my shirtsleeve up to my mouth, trying to clear my breath of the taste of salamander smoke.

“I love the purple smoke part!” shouted the witch. “I hope you’re watching, Camellia. Someday I’ll teach you all this.”

“Not a chance,” I said, thinking of all the animals that had to snuff it to make this spell of Sarmine’s. “I wouldn’t summon a demon for anything. You can’t make me into a witch. You can’t make me be like you.”

The witch’s exaltation dissipated and her spine stiffened. “Recipe done,” she said shortly, not looking at me. “Now the words.”

“Except for the pig’s ear, right?” I said. My voice hardly wobbled.

“The what?”

“Except for the pig’s ear. I didn’t get you the pig’s ear. So you can’t summon the demon, because you’re missing an ingredient.”

The witch laughed from deep in her gut, her salmon ruffles shaking. With effort she composed herself. “I shouldn’t laugh—it’s too ignorant to be funny,” she said. She wiped her eyes with a bit of lace and explained, “The pig’s ear is for Wulfie to chew on. So he’ll stop chewing my good shoes.”

A dog toy. A stinking dog toy. “And the rhubarb?”

She shook her head. “‘Stiffening, straightening, sharpening,’ Camellia. You claim to do so well in that school. Don’t they teach critical thinking? The rhubarb was just a red herring.”

That was it. That was my last chance, and the witch was starting her incantation. “AH-beela AH-beelu, aBEElu, aBEElu…” she repeated. Blue smoke gathered in the pentagram. It coalesced from the chalk dust, rose up in the air, and filled an invisible pentagonal column with thick blue gas.

The scent of sulfur and rose petals filled the air. It grew very hot and my damp shirt clung to me. I sweated buckets, though the witch stayed dry as dust, her silver hair as crisp as ever. “Is this how it’s supposed to go?”

“Progressing nicely!” shouted the witch. “Now watch this!”

She flicked her wand at the pentagram and a prism of glass shimmered into view, enclosing the pentagram and the blue gas. One more flick and the blue gas shot upward as if sucked into the ceiling by a vacuum cleaner.

When the gas cleared, there was the demon.

4

Boy-Band Boy

The demon was nine feet high. He had orange horns circled by a brush of thick red hair. No, wait. They were green horns circled by a brush of thick blue hair. His skin was yellow, then it was turquoise, then it was baby blue. His size and shape didn’t change, but all his colors did. It was like watching a living rainbow.

“Estahoth Elemental, Demon of the Fourth Layer, Second Earl of Kinetic Energy, do you agree that this is your correct and full address?” said the witch in a resonant voice.

“I do,” said the demon in a voice like thunder.

“Then I propose to you the binding by which you may spend a short time on earth. One, I need a hundred pixies in Hal Headley High School on Friday, dead or alive. Two, I need precisely what this spell is asking for when it says, and I quote, ‘the hopes and dreams of five.’ Three…”

There was a taut silence, and then Sarmine continued. “You are no doubt familiar with the air elemental known as the phoenix, though you spend your time in the Earth’s fiery core. As phoenix keep to the mountaintops, they have not been destroyed by humans as so many of the dragons were. Still, they live where we cannot reach them. Witches have named and numbered them over the centuries, tracking their hundred-year cycles. There were very few that lived at the altitude of this city.”

“I am familiar with phoenix, yes,” said Estahoth. “Do not presume that you are the first witch to summon me. I am no virgin.”

He leered at us, and despite the danger, the expression reminded me of someone imitating Elvis Presley. I clapped my hand to my mouth, choking down a burst of hysteria.

“Quite,” said Sarmine. “Then you know how much power is contained in the phoenix’s hundred-year death and birth.”

“Atomic,” the demon said simply.

“There is a phoenix known as R-AB1 which is due for its hundred-year explosion on this Halloween. This Friday evening at eight-forty. Indeed, Camellia and I settled in this town fifteen years ago to keep an eye on it. But fourteen years ago this phoenix disappeared.”

“It could be anywhere in the world,” scoffed the demon. “That’s a needle in a haystack.”

Sarmine raised a finger. “I have recently learned that when the phoenix disappeared, it was transfigured and hidden somewhere on the grounds of Hal Headley High School. You will find it by Friday, and then funnel the force of its magical explosion into my spell at my command.”

“Pixies, hopes, and Phoenix Rabby,” said the demon. “Check, check, check. Anything else?”

“Hold up,” I said. “Just what do you mean by this ‘hopes and dreams of five’ stuff? And a what, a frikkin’ atomic phoenix explosion at my school? What exactly is your plan here?”

The witch ignored me. Of course. I get no say in anything.

“Anything else?” repeated Estahoth.

“Well, since you asked so nicely—Moonfire’s chest has been bothering her,” I said. The witch glared at me, but I glared right back. “He’s here, isn’t he? And you said only an elemental could work magic on another elemental.”

“I’m not glaring; this is my happy face. I’m pleased you’re taking an interest,” said the witch. Which of course made me bonkers because she knows perfectly well the only thing of her world I love is that dragon. “Estahoth, would you mind taking a look at the dragon’s lungs?”

“Dragons, phoenix … nothing I’d rather do than play vet all day,” said the demon. “Still, as long as I get my chance at embodiment I’ll shake on it. Oh, I have such plans to rule your funny little world.”

“I imagine,” said the witch dryly. “Just don’t think you’ll get to fulfill any of those plans.”

“Out of curiosity, why didn’t you call the demon you called last time?” said Estahoth. “Nikorzeth’s biggest hope in embodiment is to be another WitchNet star like Chadzeth.”

“Because I need someone who can control a phoenix explosion,” said Sarmine. “Such an opportunity comes rarely. I intend to combine one phoenix explosion plus the pixies plus the hopes plus many other secret ingredients to work the most powerful spell ever seen in this town. And to control this explosion will take not just an elemental, but a powerful elemental.” The witch did not flatter or butter up, so I expected all this was nothing but the truth. “It takes someone more clever and powerful than Nikorzeth, poor fellow.”

“Nikorzeth wouldn’t know his own rear end if it were transformed into his elbow,” Estahoth said. He smirked and it seemed like the demon and the witch shared a moment together, amused at the weakness of poor Nikorzeth. “Is that all?” Estahoth said.

“With one clause,” said the witch. “Whether or not you complete my tasks, you will leave the instant the explosion of R-AB1 finishes. I’m aware that demons are bound by their own natural laws to complete contracts. But even if you fail at my tasks, you don’t get to stick around.” She drummed her fingers on her arm, considering. “That is all.”

The demon puffed up, chest out, rainbows rippling. “Fantastic,” he said. “Now do you want to hear my plan? My plan is to set up shop in the nice new body you give me and eat its soul.” He pointed a sunshine-yellow claw at me. “That one looks young and healthy. Good choice. Once I achieve embodiment, I’ll take over the world. Demon power here on earth, with no restrictions? I’ll be unstoppable.” He mwa-ha-ha’ed very impressively. “I’ll outlaw all the witches so no demons can follow me. I’ll control everything. How do you like my plan?”

“Hmph,” I said. “I may not agree with her methods, but the witch will make you do as she says. I wouldn’t mwa-ha-ha so fast if I were you. Right, Sarmine? Right?”

The demon smirked.

Sarmine shook her head. “No, Camellia. I cannot compel an elemental to do my bidding. What I can do is create an agreement we both bind ourselves to. If he wishes to spend time on earth, he will accept the obligation I wish him to fulfill. As demons think, quite incorrectly, that they are smarter than mortals, they always accept these agreements in hopes of stretching their contract long enough to achieve embodiment.”

“Your souls are puny,” growled Estahoth. “To let me roam around, you have to give me a body. Once I have a body, I can seduce that body’s soul and then I am free. Free to live on Earth!” He roared the last line.

“Which is why I have procured you a mannequin,” said the witch. Her heels clicked as she crossed to the pentagram. Her finger stabbed at the red-shirted figure slumped in the card table chair. “I have fed that mannequin one drop of dragon milk each day for the last twenty years,” she said. “It has enough elemental magic to mimic a human body for three and a half days. That will be exactly enough time for you to complete the work I expect of you.”

“This?” Estahoth peered down at the wide-eyed mannequin in the T-shirt. He poked her plastic shoulder. She tilted on the chair. “Are you as mad as a hatter? No. Can’t be done.”

The witch’s dry lips cracked a thin smile. “I’ve done my research,” she said. “In 1211, a demon named Hebroth was able to live on earth in an elemental-infused golem for one week. In that case, the golem was stuffed with phoenix feathers.”

“Really?” said Estahoth.

“The demon might have been able to stay longer,” said the witch, “except that, unfortunately, the mixture was not pure. There was a match mixed in with the phoenix feathers. As it jostled around, the feathers burst into flame and destroyed the golem. And, regrettably, the demon.”

Estahoth’s chest rippled red, purple red. He circled his pentagram prison, shimmering red hot. “Your kind does not call us so often anymore. I have been waiting to be released from the tormenting fire of the eEarth’s core. Waiting for my chance to live.” His voice rose. He had great vocal support for someone with no diaphragm. “And now, you offer me this thing with no soul? Bah.” He backhanded the mannequin and it smacked to the floor, bounced against the glass wall of the pentagram. “That is not playing the game fairly. I am deeply offended, Sarmine.”

“Your offense bores me,” said the witch. “You are contained in my pentagram, so you only have two choices. Accept my offer and have the mannequin for your earthly body. The goat’s blood will bind you to it so you cannot leave it for a human body. Or, go home. Which is it, Estahoth?”

Estahoth put his arms out, as if testing the glass walls of the pentagram. Then the rainbow colors shimmered and his body dissolved. The rainbow lit up the glass like a prism for one gorgeous moment. Then with a swoosh, all the rainbow light went into the mannequin. It levered to its feet, awkwardly. Seemed to sniff the air. Sniff its fingers, like it was examining the spell that bound it. It pressed its stiff fingers against the glass.

“I accept,” Estahoth said. The mannequin’s lips did not move.

“Well chosen,” said the witch. She touched her wand to the glass and inscribed a door.

The glass melted away and Estahoth stepped into our world. The rose/dragon/salamander smell dampened, replaced by a wet, moldy scent I last smelled when our basement flooded. Mold. Mold plus the sharp scent of firecrackers; that was the scent of this demon.

The demon-mannequin creaked around the basement, testing his limbs. The mannequin’s cheekbones were chipped where she’d struck the floor, spots of white against the pink. Her painted eyelashes made her eyes seem wide with fear.

I swallowed. “Doesn’t look very real,” I said. “How do you think he’s going to get around town looking like that?”

The mannequin swung around to look at me. It fixed me with painted black eyes.

Then it collapsed to the cement floor in a clattering pile.

The rainbow light rushed out of it and against me.

It was like standing in a tornado. The light had a force that beat against me like thunderous wind, battering me down with firecrackers and mold. I staggered, my back hit the wall, and then there was nowhere to go. “I thought … you said … goat’s blood would contain him!” Instinctively I pushed against the rainbow light as hard as I could. The witch’s demon was no way taking me over.

My eyes watered from the strain. My bones felt like they were being both squeezed and ripped apart at the same time. I pushed and pushed and pushed—

and then suddenly, I tumbled forward onto the dusty basement floor as the demon withdrew, my hands smacking the cement. The rainbow light compressed, gathering force. “That wasn’t goat’s blood,” he said in a pitch like struck crystal.

Then he rushed the witch.

This shows you how strong the witch is. She beat that tornado-force elemental back with the kind of glare she gives me for breaking the dried snakeskins.

The rainbow light filled the mannequin and it stood up. It wobbled on its jointed high-heeled feet, unsteady. If a mannequin needed to breathe, it would be breathing hard.

“Oh, please,” said the witch. “You think we’re not both well shielded? I’d just like to see a demon get into anybody with witch blood. Now tell me, Estahoth. What kind of blood was it?”

Stony silence.

“What kind?”

“Cow’s,” the demon said, and laughed sharply. “Not even strengthened with werewolf dung. I thought you knew bovines weren’t good for anything but love potions and lucky charms.”

The witch didn’t spare the energy to look at me, but my jittery heart sunk to my tennis shoes regardless. Cow’s blood! Had Kelvin always been giving me the wrong stuff, or was that his mom’s doing?

The mannequin rocked back and forth. “You can’t keep me away from humans forever.”

“Yes, I can,” said the witch calmly. “I have plenty of control over that plastic carapace.” She pointed her wand at the demon. “Back in the pentagram you go. We will try this again tomorrow with real goat’s blood.”

The mannequin rocked toward the pentagram. I could tell that the witch, despite her calm words, was under a tremendous strain. Her left hand, hidden behind her back, was clenched and knotted as she tried to drive the demon back into the pentagram through sheer force of will. And so forceful was Sarmine’s will that it seemed, almost, she was winning.

I held my breath, not daring to disturb even the air in the basement as Sarmine pushed the mannequin toward the pentagram.

And then the werewolf cub burst through the basement door and skidded down the steps, an entire bag of barbecued pig’s ears swinging from his jaws. A blond boy thumped down after him. “Not all of them,” he shouted. “I need those for Bingo! Heel, boy, heel!”

Wulfie ran smack under the mannequin’s legs, jolting the demon out from what little control the witch had on him. Over they went in a pile, and the pig’s ears flung from the bag, skittered across the cement floor.

Devon skidded to a halt and looked around in amazement at the scene in the basement. His eyes met mine. “Oh man,” he said. “I didn’t mean to come in, I mean, I was just chasing … I mean, your dog nearly took my thumb off grabbing that bag and—”

The rainbow light surged from the mannequin, bigger, wider, flashier. It grew and grew toward Devon.

“Devon! Run!” I shouted.

He tried to obey, but his foot slipped on the pile of pig’s ears and he windmilled. Wulfie ran around his legs, howling.

The witch grabbed powders from her fanny pack, shouting the first part of a spell—

But we were all too late.