opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

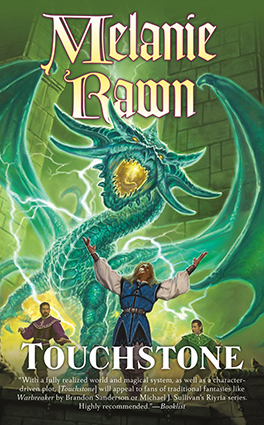

opens in a new window Welcome back to opens in a new windowFantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from opens in a new windowTouchstone by Melanie Rawn, the first book of the Glass Thorns series. In Albeyn, theater is shaped by the magic of skilled practitioners into a complete sensory and emotional immersion. Catch up before the next book in the series, opens in a new windowPlaying to the Gods, comes out August 29th.

Welcome back to opens in a new windowFantasy Firsts. Today we’re featuring an extended excerpt from opens in a new windowTouchstone by Melanie Rawn, the first book of the Glass Thorns series. In Albeyn, theater is shaped by the magic of skilled practitioners into a complete sensory and emotional immersion. Catch up before the next book in the series, opens in a new windowPlaying to the Gods, comes out August 29th.

Cayden Silversun is part Elven, part Fae, part human Wizard—and all rebel. His aristocratic mother would have him follow his father to the Royal Court, to make a high society living off the scraps of kings. But Cade lives and breathes for the theater, and he’s good—very, very good. With his company, he’ll enter the highest reaches of society and power as an honored artist—or die trying. Cade combines the talents of Merlin, Shakespeare, and John Lennon: a wholly charming character in a remarkably original fantasy world created by a mistress of the art.

Chapter 1

Predictably, the girl was willing to draw the pint only when the coin was glinting on the bar. Cayden stretched his lips in a parody of a smile as she scooped up the money with one hand and pulled the tap with the other. No glass for him, oh no; leather tankard instead, sealed with tar and riveted with brass and bound to taste of both.

Well, it was alcohol, and that was all that mattered. But if that fool who’d had the bollocks to claim himself a glisker had been any good, Cade would be knocking back whiskey right now, and plenty of it—from a real glass, and with coin to spare for something to eat. Decent drink and his supper had walked out of the tavern a little while ago, jingling in the incompetent’s purse. Glisker, he’d termed himself. Experienced, even. Cade snorted. Probably had about as much Elfenblood in him as the dirty rag the girl was using to mop up the bar. At least he was paid off and gone, and nobody was any the worse for the performance.

Yet when Cade thought about what might have been, if he had the right glisker, one with real talent and real magic—

“Wuzna too gude, wuzzee?”

The accent was excruciating—especially as Cayden had worked so hard to soften his own, distorted during years of schooling not twenty miles from here. Eyeing the young man beside him at the bar, he noted a confusion of features that proclaimed an ancestry so diverse that probably even he didn’t know what to call himself.

“No, he wasn’t too good.” He had to admit it. Honesty was the hallmark of a real artist, or so his Sagemaster had told him. Or maybe it was “truth” that mattered most. They weren’t the same.

“Gotz me a chum c’n do ooshuns better,” the rough voice continued.

“Do you?” Cayden smiled politely and returned his attention to his ale.

“Domn near purely breeded Elferblud, an’ tha’s fact. Givvem withies next show, whyn’t ya?”

Yet another aspiring glisker. Splendid. What was he, the audition manager for every amateur in the kingdom?

Still … they’d gone through four gliskers this year alone, not counting the idiot tonight, never finding the right mix, never finding anyone Cayden could trust with his visions and Jeschenar could trust with his skin and Rafcadion could trust with his sanity. They weren’t anywhere near good enough even to seek Trials, and it was all because they didn’t have the right glisker.

What would it be like, he wondered, to experience that effortless balance of talent and energy and magic that this was supposed to be? It was what all the greatest players had known, what he sensed was going on with the Shadowshapers now that they’d hired Chattim Czillag away from his old group. That nobody had ever heard a name so outrageous, nobody knew where he’d come from or his lineage or the name of his clan—if any—or indeed aught about him mattered not at all. Chattim fit. With the right glisker, a performance became an event, a distinction.

Hells, what was one more tryout, anyway? It wasn’t as if anyone would ever hear about yet another botched playlet, not in this rickety old tavern only half a step inside civilization.

Cade shrugged to himself and glanced down—way down—at the youth beside him. “All right, send him up for the next show.”

Breath hissed between ragged teeth—a sign of delight in a Troll, and of an impending brawl in a Gnome. As he hurried off to find his friend, he moved with the rolling shoulders and splayed knees peculiar to the former, thereby settling the question of his primary ancestry as surely as Cayden’s long-boned height proclaimed his. Watching the little man, recalling the quirks of his accent, for an instant Cade felt a twinge of longing for home. Not for his parents; a bit for his little brother; mostly for their Trollwife, Mistress Mirdley. She’d been strict and kind to him, when all his mother knew how to be was neglectful and harsh.

“Oh, pity the poor little Wizardling!” jeered the Sagemaster’s voice in his head. “How horrid to be you!”

A small commotion behind him jostled him into the bar, and he turned his head to snarl. One more trite old playlet tonight for this unsophisticated crowd, and they could get out of here, get some sleep in the hayloft, and then tomorrow be gone entirely from this village of sour ale and foul manners. And really lousy trimmings, he thought with a gloomy sigh; two nights of this, and they’d barely made enough for the coach fare home. He thought with longing of the brand-new private coach his friend (and rival, though nobody but Cayden knew that yet) Rauel Kevelock had so gleefully described last month, painted in swirling colors like a demented prism, with SHADOWSHAPERS in stark black on both sides. It had bunk beds for when they got tired, and a firepocket for when they got cold. True, the group still had to hire horses from the post stations, but at least they were no longer at the mercy of worn-out springs and a coachman who drank his wages in full before clambering up to take the reins, and—

Someone bumped into him again, knocking his hand against his leather flask of ale. He half-turned and shoved right back. Spindle-boned Cade might be, but Jeska had taught him how to use his fists efficiently rather than his magic haphazardly, and he was just frustrated enough right now to relish the prospect of a punch-up.

Then he saw what had knocked into him.

Even for someone with plenty of Wizardly blood, Cayden was tall. The man whose chest was on a level with his eyes—this man was at least half Giant. Maybe more than half; there was very little mitigating intellect visible in the red-rimmed eyes glaring down on him.

“Uh—sorry,” Cade managed. “Thought you were somebody else.”

“Did ’ee, now?” The depth of his rumble rattled the bottles on the shelves.

Oh, shit.

“Yazz!” exclaimed a light, cheerful voice. “Don’t break him! He’s me new Quill, he is! It’s rich an’ famed he and me will be—but only if ye leave him all his wits an’ bones!”

A slow, fond smile gentled the massive face. Cade turned, wondering if he was more grateful for the rescue or annoyed by the glisker’s arrogance. Because a glisker this had to be, the one promised by the Troll. For an Elf, however, this boy had peculiar taste in friends.

And then all speculation—indeed, all thought—fled Cade’s brain, except for the sure knowledge that he would remember for the rest of his life the instant those huge, melting eyes looked up at him from beneath a shock of coal-black hair.

Those eyes: sparkling with what his Sagemaster called “front and effrontery,” a combination of awful nervousness and awe-inspiring conceit. Cade had been accused of it himself on occasion, but hard lessoning in the brutal school of his own family had taught him to hide any fear behind all the arrogance he could possibly project. This boy was too young yet to have perfected his mask.

Those eyes: a bit too bright with the alcohol downed to get his courage up, trying to hide apprehension that Cade wouldn’t think he was good enough, but not trying at all to disguise that he thought any group of players would be colossally lucky to get him.

Those eyes: full of anxiety and arrogance, innocence and cunning, and a dozen other conflicting things that dizzied Cade for a moment.

There was a low growling in his ears that he hoped was Yazz agreeing to let him live. A burst of bright laughter followed from the Elf. His new glisker.

Those eyes were directed at him again, calculating, challenging. “Mieka say-it-five-times-fast Windthistle.”

“Dare ’ee t’try!” The Giant nudged Cade with an elbow strongly reminiscent of a roof joist, and he staggered against the bar.

“Did I tell ye or did I not, Yazz? Don’t damage him!”

“Much beholden,” Cade said, taking refuge in the stock phrases of civility. “You’re the glisker wants a chance?”

“You need me, and here I am. Thought I’d introduce meself afore we start work.” Thick black brows arched an invitation to share his name.

“Cayden Silversun, Falcon Clan,” he said.

To his annoyance, the Elf didn’t look as impressed as he ought to have done. But there was an odd sort of approval in his eyes, and perhaps relief, as he said, “Falcon, not Hawk? Good. Such a harsh, cruel word, innit? Typical of that tongue—and that clan. Always makes me think of claws with blood drippin’ off ’em. Met any foreign kin?”

“No. Are you ready to work?” He cast an eloquent glance at the whiskey in Windthistle’s hand.

“Almost.” He slugged back the remainder of his drink, slapped the glass onto the bar, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand, belched delicately, and gave Cade a dazzling smile. “Now I’m ready.”

Yazz reached out a finger and tapped a carefully gentle admonishment on the Elf’s head. “Rich un’ famed, Miek,” he rasped, and Cade had the irrelevant thought that meek was precisely the wrong word for any Elf, particularly this one.

“Oh, certain sure,” the boy laughed, and scampered off towards the tavern’s pathetic excuse for a stage.

“Givvem simple t’do,” said Yazz. “Makes everythin’ from nothin’, Miek does.”

“Is that so?” Hearing the sharp skepticism in his own voice, he dredged up a smile meant to mollify the Giant. “I’m looking forward to it.”

The trouble with being the tregetour, Cayden thought for possibly the millionth time, was that after you were done with your part of the piece, you were helpless. Superfluous. At times, a nuisance.

No, that was wrong, he thought morosely as he crouched before his glass baskets of crystalline withies. The worst part of it was having to trust.

Rafcadion and Jeschenar, them he trusted. It wasn’t their fault they’d never found a glisker who really knew what he was doing—or, more to the purpose, knew what to do with Cade’s magic. Jeska was a good masquer, and getting better—and Cade knew that a lot of the reason they’d gotten as far as they had was that Jeska really could make much out of practically nothing. Rafe was just plain brilliant: steady, calm, powerful, everything a fettler ought to be and more. But Cayden couldn’t help wondering what it would be like when Rafe didn’t have to use up so much of himself keeping the performance together because the glisker was lazy or erratic or reckless; when he could fine-tune things, work with the man instead of guarding against excesses, correcting failures, glossing over incompetences.

Given a glisker who could not only perform the piece but also enhance it, Jeska and Rafcadion would be free to develop their gifts to their fullest, to provide Cayden’s work with the nuances he craved. And they would no longer end each evening so wrung out they could hardly stand.

Despite Yazz’s affectionate confidence in this new glisker, Cade had no hopes for him. He’d never known of any Elf from that kin line who even aspired to what the Troll and the Giant claimed this one could do. All Elves were maddeningly insubordinate, but the Air lineages added a wicked capriciousness to the mix, just as the Earths were devious and greedy, the Waters were sullen, and the Fires were downright malicious. Cade doubted that this Elf could sit still long enough for a performance.

Things definitely ran in families; he knew that for a fact. His mother’s great-grandfather—the one without a title, the one she never talked about—had been a noteworthy poet. His father’s father had been a Master Fettler who’d performed on the Ducal Circuit. Some of Cade’s cousins participated in amateur theatrics—though none of them would dream of making it a profession, for more money and status were to be had in other Wizardcraftings. His uncle had begun a promising career as a fettler before being called up into the army for that despicable experiment that had killed so many—and left others drooling imbeciles, like Uncle Dennet. It was a grudge Wizards had against Elfenkind, that they had flatly refused to participate in the Archduke’s scheme to use magic as a method of war, and had thus escaped tragedy.

That this Mieka Windthistle had no ancestors Cayden knew of who’d ever worked in theater boded ill. Then again, maybe his circumstances were like Cayden’s: a talent that simply would not be stifled, a restless need to create that could not be channeled into more respectable ways of making a living. Maybe he had chafed and rebelled as Cayden had, until finally his parents gave their unwilling consent to let him try.

And if that was indeed the case, he wondered if, like his own parents, they expected him to fail.

The claim to “purebred” he dismissed as absurd. How many centuries since the last truebloods of any race had died? He could trace his own ancestry back seven generations in his father’s line, and fully twelve in his mother’s. In their long, long history had been some genuine oddities, but his mother considered him the oddest of all. “Something must not be quite right on your father’s side,” she’d mused more than once. “My people never threw such a mongrel as you.” He knew by the names alone that he had Wizard and Elf (two Water, one Fire), Piksey and Sprite, and even that rarest of all bloods, Fae, in him. And Troll, he’d heard his mad great-granny say, because where else could he have got a face like this? Hook-beak nose and long jaw, cheekbones that could cut glass, wide mouth—granted, he was tall and gangly, not short and stout, but the byword for ugliness had stuck to him like pine sap, and every nickname he’d ever been inflicted with and every insult ever flung his way incorporated troll amongst its syllables. Never mind that his eyes were the fundamental truth about him: a clear, luminous gray, like the moonstones in Queen Roshien’s crown. They were Elfen eyes, inheritance of Mistbind and Watersmith, just as his long bones and thin, strong hands proclaimed Wizard, and his straight white teeth were entirely Human.

But it was the gift he never spoke about that was proof positive he was Fae. How all these things had combined to create him, he neither knew nor cared. He was what he was, and he knew what he could someday be. He’d seen it.

But … trueblood Elf? Not damned likely. Usually the bit remaining showed only in the coloring—the very dark, the very pale. Black hair, and eyes brown as tree bark or green like a forest pool, and skin the golden brown of fallen leaves. White-blond hair, with eyes blue as ice or gray as snow clouds, and translucent milky skin. The other features—delicate little hands and feet, sharp teeth, pointed ears—those things seemed to have faded first from the bloodlines.

If they reappeared, they were quite often hidden somehow. There were chirurgeons who did a brisk business in mutilating a newborn’s ears (as had been done to Jeska at the orders of a grandfather frantic to be thought entirely Human), and grinding down or knocking out and replacing any suspect teeth. Hands could not be hidden, but feet could be broken at the instep to flatten the telltale high arch. There were dyes for the hair and cosmetics for the skin, and specialists who retrained the lilting voice—or broke the willful spirit.

Nothing had been done to disguise this boy. Nothing. He was Elfen from his thick hair to his small, high-arched feet. Moreover, he had inherited the most attractive aspects of both major Kins. No Dark Elf would have skin as purely white as his, with no brown freckles or brick-red mottling, and no Light Elf would have hair that black. Those eyes confirmed it: neither gray nor blue, neither green nor brown, but an almost opalescent combination of all those colors, with an elusive golden spark in the iris of the left eye. It just wasn’t right that anything male, even Elfen male, should have eyes that beautiful, with such long, thick lashes. The teeth were small and regular and entirely Human; the ears, peeking shyly from the heavy silk hair, were entirely Elfen. It was a quick, wickedly nimble little body, and the fine bones were long enough to give him Human height. His voice was soft and lively, deeper than a young Elf’s treble. And his spirit was untamed—and, Cayden suspected, completely untamable.

He was the most beautiful thing Cayden had ever seen in his life. And he was asking to be given a chance.

So: should Cade give him something simple, as the Giant had suggested, something to ease him into it, give him the opportunity to succeed? Or something complex, difficult, to challenge the arrogance in those eyes? For Cayden realized that Mieka Windthistle wasn’t asking for anything, any more than Cayden had ever asked his parents’ permission to become a player. He was demanding control of Cayden’s glass withies, and Jeschenar’s absolute trust, and the entirety of Rafcadion’s supportive skill. Arrogant little Elf.

Cayden crouched down beside the glass baskets, his lips softening in a smile. Woven of ropes made of clear glass, there were two sets of four baskets each, the smooth curved rims tincted in sequential rainbow colors. Within were distributed almost three dozen hollow glass twigs varying in length from half a foot to nearly thrice that, crimped at one end and stamped there with the glasscrafter’s hallmark, their colors more delicate. The withies trembled with random sparks, reacting to the proximity of the one who had imbued them with magic.

He and Rafe and Jeska had thought to do another classic tonight, a cloying sentimental piece about a sailor coming home rich from his voyages to find his girl bespoken to another man. It was simple enough, requiring a masquer to shift only twice, from the sailor to the girl and back to the sailor again. There was magic and more than enough in the withies already primed. Simple magic for a simple story. Had he been forced to do the glisking, as he would have had to after the departure of the talentless idiot if Mieka Windthistle hadn’t shown up, these withies would have been sufficient. He had enough Elfenblood for the work, but a restrained magic was all he could handle on his own. It wasn’t that he was incapable, he told himself, it was just that he was so much better at the creating than the working. But he had to be honest inside his own head: He was clumsy at best, his hands too big and his fingers too long for the delicate manipulations required. With a quick glance at Mieka, who was over in a corner sharing a laugh with his Giant and Troll friends, he decided that the magic inside the slender glass twigs was too simple. On impulse he grasped a handful from the far basket, the indigo one. A few moments’ concentration imbued them with fresh spells. A second basket, and a third, and he breathed deeply before rising to his feet again. Let the snooty little Elf give this a try, he told himself, and went to talk to Jeschenar and Rafcadion.

“You really want to?” Jeska asked, frowning all over his gorgeous golden face. “I’m game, of course I am, but—”

“You’ve Elf enough in you to supplement whatever he can’t do. I’ve watched you work this one when you’re so drunk, you can’t hardly see straight.” To Rafe, he added, “I’ll tell him he’ll have more than the usual to work with on this piece, but if you catch him messing about, slap him back down.”

The fettler shrugged powerful shoulders and nodded. “I’ll keep him in line. No flourishes.”

“Oh, you can tease him a bit. Just don’t let him get away with anything silly.”

Ten minutes later, watching from his hiding place beneath the stairs—hiding not to avoid seeing the audience’s reactions but to avoid their seeing him—he clenched his jaw and his fists and prayed to the good Lord and Lady to protect his friends if this new glisker should prove not just arrogant but dangerous. Still, their long search for the right glisker had taught them to deal swiftly with the inconsistent and the incompetent, the nervous and the confused. Jeschenar was strong, with great instincts; Rafcadion was capable of throttling any flawed or frantic magic. And if needs must, Cayden could summon up his own skills and help his friends.

Expecting the boy to wait politely beside the glass baskets while Jeska readied himself and Rafe took a position at far stage left, Cade was startled when the glisker charmingly persuaded a couple of patrons out of their chairs and dragged the furniture to the back of the stage. Then he began rearranging baskets. Quick hands switched green with blue, yellow with violet, perched the black and white onto chair seats and balanced the orange on their slick rims. Then he seemed to be looking for something. Not finding it, he shrugged—and picked out two withies from the red basket to balance across the blue. It was a configuration that made no sense to Cade at all, who always used the classic prism pattern. Then, rather than seat himself on the glisker’s bench within easy reach of all the baskets, he remained standing. When Jeska nodded to Rafe that he was ready, and Rafe began the foundation work—steady and solid as always, the best fettler Cade had ever encountered—the glisker bounced a few times on his heels, laughing soundlessly to himself.

Magic began to radiate through the tavern. Usually Cade spent a few moments watching the audience, marking those who resisted and those who instinctively fought, just in case his help might be needed. It never was. Rafe was too good at control. But vigilance was another duty a tregetour owed his group. Tonight, though, he completely forgot. The Elf did something he’d never seen a glisker do before, not even the Winterly or Ducal or Royal Circuit professionals.

He made his work into a dance.

Instead of sitting where he could reach for one withie at a time to have it ready in the left hand for the switch to the right when needed, he twisted and curled his whole body, swaying from one basket to another, grabbing up glass twigs in both hands and waving them like a Good Brother censing parishioners at High Chapel. Cayden bit back a despairing moan. If the boy was this wild just setting up the scene, who knew what he’d do with the piece itself?

Mieka played it straight for the Sailor’s homecoming. A mast and a white backdrop sail, and a wooden deck below Jeska’s feet: all these things were usual. The hint of salt air, the touch of a breeze, even the dim ring of ship’s bells calling the hour—all were subtle touches usually found only on the Circuits. But when the Sailor set foot on land and caught sight of his beloved in the company of another man, instead of the outrage and pain and betrayal the piece called for, Mieka projected shocked amazement without letting the audience—or poor Jeska—in on why.

What he had in mind became apparent when Jeska made his shift to the persona of the Sweetheart. At first she was as the Sailor had remembered and described her: a lovely, dainty little thing with blond curls and a winsome smile. But quickly the demure blue gown deepened to a vile purple; the shawl turning from leaf to livid green; the gold hair brassy; and the petal-pink lips blood-crimson as the glisker conjured the painted face and blowsy figure of a seasoned whore. She lamented how hard she had to work, how difficult her life was—all with Jeska behaving physically as if he wore the usual pretty face and graceful form. The audience howled with laughter and pounded tables with fists and flagons. As she bemoaned the fact that she’d had to accept the other man’s proposal because it just wasn’t possible for her to go on any longer alone and unprotected, Jeska did what he always did at this point—what, by tradition, every masquer did at this point: sank to his knees. A pitiable gesture for a young girl, it now looked as if she was kneeling to perform certain services.

Jeska held the pose, then got to his feet almost as if pulled upright by powerful, unseen hands on his shoulders. By the time he was standing, the shift back to the Sailor had been made. Cayden swallowed a gasp of shock at the glisker’s skill—and nearly strangled on an exclamation when he sensed Rafe loosen his stringent hold on the flux of magic. The Sailor told his former girlfriend that it was breaking his heart but he understood, he’d been gone a long time, it was only natural that she’d grown tired of waiting—and all the while the Elf emanated waves of gleeful relief at this lucky escape that washed over the eagerly receptive audience. At the end, the Sailor was supposed to slump into a tavern to drown his sorrows, dejection in every line of him as he dropped coins on the bar and bought drinks all round so he’d have company in his despair. By now Jeska had adapted—oh, had he ever adapted. Jaunty and carefree, whistling in between his lines, he dug deep in pockets and flung coins high in the air as he invited everyone to toast his freedom. The imaginary coins were one of Cade’s best feats of magic, something very few tregetours his age could do; their cheery chiming was all Mieka, and something no other glisker had ever managed to do for Cade before.

It was funny, it was brilliant, it was completely outrageous, and it had the patrons flinging real coins onto the stage.

The Elf had one more trick. As Jeska bent to retrieve the money, he suddenly wore once again the Sweetheart’s garish gown and brassy curls. Startled, he nearly tripped on his own feet. Cayden heard Mieka chortling behind the glass baskets. Jeska again reacted swiftly, changing the crouches to curtseys, blowing kisses to the audience. And the trimmings piled up in his swift, snatching hands.

It was a while before Cayden felt ready to leave the darkness beneath the stairs and shoulder his way through the crowd to the bar. The whole village was congratulating the Elf, buying him and Rafe and Jeska drinks, roaring out the stale old lines that Mieka had turned from histrionic to hilarious. When Cade at last ventured out, he was swept up in the general celebration of the glisker’s triumph.

He had never been so furious in his life.

He wasn’t so furious that he turned down the chance to get drunk for free.

Neither was he so drunk by the end of the night that he neglected his duty to himself and his friends by making it easy for the tavern keeper to hire them for another night. Guessing that the coins would keep coming from the audience, Cade demanded not money but decent beds—including tonight—and three meals tomorrow instead of one, plus a full supper before they went to bed tonight and breakfast on the day they left. By the time he got what he wanted, the minster chimes had rung curfew and the place was nearly empty. Both he and the landlord knew that tomorrow night, from opening bell until closing, there would scarcely be room in the tavern to stand. He spread his hands wide open in the Wizardly gesture that meant You may trust my word, I use no magic and concluded the deal, then returned to the bar.

Rafe was superbly drunk, lids drooping over his blue-gray eyes, a silly smile curving his lips beneath the heavy beard he was very proud of being able to grow at the ripe old age of nineteen. Jeska was a little more sober, but only a little; the tavern keeper’s daughter might or might not get the full benefits of his attention later on. Cade wondered whether he ought to mention they’d be in real beds tonight, not in the hayloft, then shrugged to himself. Jeska always found a way.

As for the glisker—Mieka Windthistle couldn’t have said his own name once, slowly, let alone five times fast, without hopelessly tangling his tongue.

Cayden didn’t wait to be noticed. He poked the Elf in the ribs and demanded, “What the fuck was that?”

Big, innocent, very drunk eyes—almost entirely green at the moment—blinked up at him. “Ye dinnit like it?” Before Cade could reply, he turned to Jeska. “Sorry for that bit at the end, mate, but it were such a fetchin’ little Sweetheart, I just couldn’t resist.”

“You’re a shithead,” Jeska remarked amiably, sorting coins on the bar. “You want your share now, or after the show tomorrow night?”

“Tomorrow night?” Cade sucked in an outraged breath. How dare they decide such things without him? “Have I said yet that there’s gonna be a next show with this—this—”

Rafcadion interrupted. “This best glisker you or me or Jeska or anybody else in this shit-pit of a town ever saw? Yeh, there’ll be a next show.” He grinned, white teeth flashing in his dark beard. “And a next, and a next, and a next—all the way to Trials.” Raising his glass—they’d all been given the real thing in place of the leather—he announced, “Trials, and the Winterly Circuit!”

Mieka laughed and raised his glass to his lips—but his gaze was sharp and watchful, and suddenly he appeared considerably more sober. Cade looked into those eyes, discovered he was unable to look away. When at last he nodded, and drank the toast, the Elf nodded back, satisfied.

“Much beholden, Quill,” he murmured. “Very much beholden.”

Chapter 2

Even though he’d long since learned not to anticipate, Cayden wasn’t too surprised when he didn’t dream that night. He had both expected to and expected not to; that was the particular glorious hell of what his Fae heritage had done to him. His Sagemaster had explained it once.

“There are things that occur which are important, and things that are not. There are things that are essential, things that must happen—and things that are so trivial, they make no difference at all. The difficulty is discerning which is which. Now, what may seem obviously important—a death in the family, moving from one village to another, falling in love—might not be important after all. And things such as choosing to wear the red tunic instead of the blue, this might be absolutely vital. Simply put, you will never, ever know.

“It would be logical to assume that events, people, interior realizations that you know at once will change your life—these will be pivots from which visions will come. Assume nothing of the kind. Some of these things are simply fated. They must happen for every other thing to happen. You have no choices to make and therefore you will dream no futures. You cannot unmeet your future wife, for example. So the day you meet her, you probably won’t dream. But if you bring her daisies instead of roses, if you wear that red tunic instead of the blue, these things may very well trigger more dreams than you can keep track of—for these are the things that often determine what shape the future will take.

“So the lesson must be that there is no predicting what will set off a foretelling. What seems important may be trivial, and what seems insignificant may be critical. You cannot control your gift. You are at the mercy of fate.”

Which was why, as Cade knew very well, he enjoyed his work so much. For, during the time he spent devising his tales, he was in control.

Once his part was done, once he’d written or rewritten the lines and employed his own special ciphers that signaled the sensory underlays, he had to give everything over to Jeska and Rafe and now, apparently, Mieka. But for those hours and days of the creative process, the work was entirely his. He supposed he could learn to trust the Elf the way he trusted his two other partners.

At least—unlike their last couple of gliskers—Mieka told them the truth, that next afternoon when they met to discuss what they would perform that night. When Rafe asked a polite question about where in the village he lived, he laughed.

“Don’t live here at all! I’m as much a Gallybanker as you three.” When they stared at him, he shrugged. “Saw you last year, didn’t I, at that tavern over on Beekbacks. With a glisker not worth a splintered withie—nor the one I saw you with next, or next as well. The one last month wasn’t bad, but…”

“A cullion, he was,” Jeska commented. “Wish him good morrow, and he’d say, ‘I take it you’re planning to die before then? Lovely!’ Mean of spirit and meaner of pocket. But I don’t understand why everyone here seems to know you.”

“My auntie’s house is out on the edge of town. She’s the one as brews the whiskey.” He winked; those eyes were blue with flecks of green this afternoon. “I’d be popular and indeed beloved even if I weren’t adorable all on me own.”

“And modest, I see,” Rafe drawled.

Mieka nodded genially. “When I heard you were booked here, I decided to make a visit to Auntie Brishen.”

“You followed us,” Cade accused.

“And aren’t you glad I did?”

He sat back in his chair, rolling his eyes. “When His Gracious Majesty gives you the silver sword and golden spurs, Sir Mieka, you’ll be sure to spare a nod for us petty quidams, won’t you?”

“Don’t condemn yourself to wretched obscurity so soon,” Mieka shot back. “Tell me what you want to do for tonight, and then tell me what your thinking is for Trials.”

“That’s almost three months away,” Rafe observed. “We’ve the first of two shows in three hours.”

“Only one show tonight.” The boy burst out laughing when they stared at him. “Thunderin’ hells, I hope what’s between your legs is more use to you than what’s between your ears! They expect us at eight. We come on near nine. They expect a good giggle, and we give it to ’em—but instead of an interval, we go right into what makes ’em weep. I know this lot. They’re surly outside and mushy inside—and once they’ve worn themselves out laughing, they won’t have energy to resist a good long cry. Which is what they really want anyway, drunk as they’ll be by then.”

Cayden had the feeling this would not be the last time he’d have to struggle for control of his own group. “If they expect us at eight and we come on at nine, they’ll be so impatient and angry that Jeska will have to work twice as hard to win them over.”

“Not with me doing the glisking.” He tapped a finger down the list Rafe had given him of the works in their folio. “No … no … no—Gods and Angels, not that one!—and not that one, neither, not if you held a sword to me throat—”

“Do you ever stay still long enough for anyone to give it a try?” Jeska asked.

“Not often, and certainly not when I’m working. Not this one—but I think the sons-and-fathers dialogue would be just the thing.”

Rafe actually recoiled. “We don’t hardly ever do that one.”

“Nobody does,” Mieka responded with a shrug. “But it’s perfect tonight, and here’s why. There’s a reason this village is near empty of old men—hadn’t you noticed?”

With a suddenness that set his heart pounding too hard, Cade knew everything. “We’re on the Archduke’s old domains, aren’t we?”

“And full marks with shooting star clusters for the scion of the Falcon Clan.” Mieka crooked a finger at the tavern keeper’s daughter. “Another round here, if you would, please, darlin’,” he called, and gave her a beguiling smile.

“Not for me,” Jeska told him. “Not until after.”

Mieka shrugged. “As you will. I’ll have yours, then. What Cayden knows and you haven’t yet guessed—”

“Almost every man of military age either died or was crippled by the Archduke’s War,” Rafe said flatly. “You don’t yet know me, boy, but there’s no advantage in routinely assuming everyone you meet isn’t near as smart as you.”

Mieka had the grace to look abashed—for all of three heartbeats. “Won’t happen again. Anyway, the piece may be about the loss of three fathers in a collapsed silver mine, but that’s neither here nor there nor anywhere else for our purpose. There’s no man will be present tonight who’ll not have lost a father or a grandsir, an uncle or older brother. They’ll weep oceans. And we’ll be up to our necks in trimmings.”

Cade accepted his glass of ale before the maid could spill it—her attention was dangerously divided between Jeska and Mieka—and took a long swallow. It wasn’t polite to ask, but previous experience had made him cautious about a glisker’s willingness to work the really wrenching pieces, the ones that demanded a fettler’s iron control but a glisker’s near-total abandonment to emotion. Uninhibited expression of joy or sorrow, love or fear, was the reason no one not substantially Elfenblood could function effectively as a glisker. Elves were creatures of unabashed emotion; unruly as a rule, even the best of them were unpredictable. The worst of them … self-indulgent was a nice way of putting it.

As for the best of them … perhaps Mieka was one, though from his enthusiastic consumption of alcohol, he appeared to have fully mastered the self-indulgent part. Cade slumped back in his chair again and sipped his ale, listening as the other three discussed the proposed performance of “The Silver Mine.” There was a wild glint in those changeable eyes, granted—but there was also an intensity of purpose as Mieka plotted out the changes with Jeska and made notes with Rafe on when he’d have to exert most control. Skepticism turned to cautious admiration as it became plain that the glisker knew what he was doing.

It was odd, Cade reflected, that he’d never once had a dream—waking or sleeping—about anyone even vaguely resembling this Elf. Jeschenar had been glimpsed several times, so when they’d finally met almost two years ago, Cade felt reasonably comfortable with him from the start. Getting used to his occasionally belligerent ways had been another matter, but at least Cade knew not to challenge him physically: Jeska was effectively king of about a square mile of Gallantrybanks, with a bagful of souvenir teeth he’d knocked out to prove it. The roster of his defeated rivals had stopped growing only because these days nobody was fool enough to confront him and add another name to the list, or tooth to the collection.

Cade had known Rafe since littleschool, so the foretelling dreams about him had no power to surprise him. He was still waiting for the squat little Gnomelike man he’d seen more and more often this last year. Those dreams were comparatively forceful, the kind that flashed through his waking consciousness as well as invaded his sleeping mind. There were several other people who populated his foretellings with more or less frequency and importance. But he’d never caught even a hint of this Elf, and it confused him.

Did it mean Mieka was insignificant? Cade would never believe that. What he’d seen and experienced last night, what he presumed would happen again this evening, argued for a powerful presence in his life. But why had he never seen the boy before?

“The worst mistake you can make is to believe that you are the sole arbiter of your existence. Put another way—do you really have the arrogance to think that nothing anyone else does has any effect on you? That if you don’t envision it in advance, it can’t possibly be real? That you make all the choices?”

Mieka must be one of those people whose caprices ruled his own life so thoroughly that Cayden’s prescience was of no use at all in predicting his sudden arrival. Now that he was here, however, Cade found it equally unsettling that there had been no dream last night, not even a vague impression upon waking that something in life had changed forever.

In fact, now that he considered it, last night he’d slept better than he had in a long time. Worry usually kept him awake until sheer physical exhaustion dragged him down into sleep. He’d attributed the swift and untroubled slumber of last night to good liquor and a blissfully soft bed. But now, watching his group thrash out the details of the night’s performance, he wondered if something else might be at work here.

“Cade? Cayden!”

“Oh—sorry,” he said as Jeska’s impatience finally penetrated his self-absorption. “Have you decided, then?”

Mieka was giving him a sidelong glitter of a smile. “Remind me—why do we need you?”

Cade grinned back, set down his empty glass, and flexed his fingers. “Without me, you’d all be nothing. Are you ready to make your choices, then, Mieka? Come on.”

Together they went into the kitchen, where a large cupboard was unlocked by the glowering Trollwife who vastly resented this interruption from her bread-making—until the Elf gave her a sweetly innocent smile. Without the slightest twinge of a dreaming, Cade foresaw infinite doors being opened for them by that smile.

They took the glass baskets outside to the enclosed porch, trying to ignore the stench of uncovered rubbish bins as they sorted through for what Mieka would be using tonight.

“Who made these for you?” he asked, fingers caressing the graceful curvature of the blue basket.

“Friend of mine,” Cade answered.

Another sidelong glance, this time speculative, and a moment later Mieka said, “You’ll have to introduce me to her.”

Cade stared. “How did you know—?”

“I didn’t!” He crowed with triumphant laughter. “Quill, you really do need to guard those eyes of yours! You can turn down your mouth and knot up your eyebrows all you like, but the eyes will always give you away! Does she make the withies as well?”

“Some of them,” he admitted grudgingly. “Most of them are her father’s castoffs. I have terrible trouble priming some of them.”

“I felt that, last night.” He selected a glass twig and inspected it. “This is one of hers?”

“Yes. Even her best aren’t quite as supple as her father’s culls, but she knows me better.”

“Let’s pick out the ones he made,” Mieka instructed, “and return them for credit. Whatever skill she lacks, I can make up for. I didn’t much like the feel of some of those from last night. They fought me.”

Bemused, he helped to sort as required. Mieka made no mistakes in choosing which had been Blye’s work and which her father’s. Those quick little fingers were exquisitely sensitive.

“Bleedin’ indecent, if you ask me,” the boy muttered, tossing a withie onto the discard pile, “trying to pass off mottles like these as usable. And you were a fool to buy them, I don’t care how much of a discount he gave you. Look at the warp in this!” He held up a foot-long twig of glass tinted faint blue, and pointed to a distortion halfway down. “It’s a tribute to your skill that these do what you want them to do—but they make you work much too hard. From now on, we use only the best, right? What’s your glasscrafter girl’s name?”

“Blye Cindercliff.”

“A rare and lovely Goblin name,” he approved. “We’ll make her as rich as us—but on what she’ll charge other people,” he added with a grin, “once we’ve made her famous!”

“We can’t use her name. No Guild allows women to use a hallmark.” And thus their wares went for much less than Guild-sanctioned items, and foreign trade was forbidden to them—“inferior” goods might ruin the Kingdom’s reputation. Never mind that what Blye made was far beyond apprentice work, approaching that of Master. She, and the hundreds of women crafters like her, would never receive Guild-level prices or Guild rights.

“This is her father’s, then?” He ran a finger over the symbol stamped into the crimp end of a withie.

“Yes. You don’t seem upset that she’s a girl.”

“A knack’s a knack, no matter if it comes wearing trousers or a skirt. You say she knows you, and that’s a very good thing. Once she gets to know me, it’ll be even better.” He paused, head tilting to one side, hair shifting to reveal one pointed ear. “Forgot to ask—how well do you know her? Meaning—”

“—would I be upset if you bedded her?” Cade laughed, genuinely amused. “I’d like to see you try, to be honest.”

“Oh. Likes girls, does she?”

“Not that I’ve ever noticed. It’s not something we discuss. No, it’s just that I’ve never seen her with anybody—she works too hard, being her father’s only child and determined to learn all she can from him before he dies. After, she’ll hire another glasscrafter, to keep the Guild happy and everything looking legal. But she wants to know everything about the work so the new man doesn’t swindle her.” He rolled one of Blye’s better efforts between his palms. There was only one barely discernible bump near the crimp to mark it as apprentice work. But no bubbles, no rutilations. Blye knew what she was about, and would only get better. As the chill glass warmed to his skin, the warmth within it seemed to stir and stretch like a cat recognizing a familiar caress.

“I like her more and more,” Mieka announced. “What’s ailing her father, can I ask?”

“Lungs. He was in the war.”

Mieka shivered. “No wonder his hand slips and his breath’s unsteady, then. Is he at the blood stage yet?”

“Not quite. A year or so, the physicker says.”

Anger made him look years older as he snarled, “Damn the Archduke, and damn the Wizards he corrupted!”

It was a typical attitude for Elfenkind, but there was a subtlety of loathing that differed from what Cayden had come to expect. It was a lack of contempt, he decided as he searched Mieka’s face, and a sincere compassion for the victims. But to hear an Elf count Wizards amongst those victims … perhaps Mieka wasn’t just the better sort of Elf. Perhaps he was one of the best.

“You’ll have to change up your ciphering,” Mieka said all at once. “These codes and colors—no, none of this will work at all.”

“Are you insane? Do you know how long it took me to put that together?”

“And how many gliskers have you explained it to?” He tapped the page of performance notes. “I don’t want anyone stealing and copying. So there’ll have to be a new cipher. I’ll help.”

“Kindly of you,” Cade snapped.

“Not at all,” Mieka replied blithely. “We see things in the same colors, you know. It’s alike to the quality as makes Chattim so good with Vered’s work—but with Rauel’s, not as much.”

“How do you know that? And how do you know the Shadowshapers, anyway?”

“And that’s another thing. We need a name, and a good one. But I’ll help with that, too. Anyway, all you and I need do is settle on a color arch, organize the subtleties, and code everything so just the four of us understand it. A night’s work, if the whiskey’s good enough for inspiration.” He smiled. “I’ll ask me auntie to contribute to the cause, shall I?”

“Anything else about our lives you’d care to rearrange?”

“Well…” Critically, gaze flickering down and up Cade’s frame. “The clothes could use a tweak. Yellow just isn’t your color. You ought to wear something silver or gray, always, to play on your name and play up your eyes. And do stop trying to grow a beard, Quill, you’re only embarrassing yourself.”

Had he really just speculated that this Elf might be one of the best sort?

“You know I’m right,” Mieka added with a cajoling smile. “I always am. But if you won’t admit it now, you will after tonight.”

It turned out he was right—about the performance, anyway. The tavern’s patrons laughed themselves silly over “The Sailor’s Sweetheart,” just as Mieka had predicted, soon forgetting that the show had begun almost an hour late. They had barely recovered their breath when “The Silver Mine” began. And they wept unashamed, also as Mieka had predicted. For all that Cade himself had been the one to supply the magic for the withies used tonight, he was hard-pressed to keep tears from his own eyes as he watched from beneath the stairs. Across Jeska’s features the anguished faces of the dying fathers melted one by one, with heartrending subtlety, into the younger, grief-stricken faces of their sons; the elusive sensations of physical pain in broken legs, ribs, fingers were diffused by Rafe carefully, gently, gliding into the emotional pain of loss as the boys bade their fathers farewell. The changes from the sunlit hill where the sons stood to the dark depths of the silver mine, with a single candle glinting that turned veins of ore to threads of light, were accomplished with breathtaking grace. The dialogue was traditional to the piece, except for a dozen or so lines Cade had changed within each section, adding and subtracting words as he sensed them needed or unnecessary. For all the familiarity of the story, there was nothing mawkish about the performance, nothing squirmy. All of it was honest. All of it was real.

He wondered what Mieka was using to produce such effects, what he was quarrying inside himself that created this art. Surely he was too young to have experienced that intensity of emotion. As the last echoes faded and Rafe allowed the magic to drain quietly away, Cade found himself doing something he never did: He joined his masquer, fettler, and glisker onstage to share, as their tregetour, in the applause.

Jeska’s arched brows conveyed his astonishment at this break with Cade’s introverted habits. Rafe’s wry smile of understanding wasn’t quite hidden in his beard. Mieka, breathing hard, damp with sweat, grinned brightly up at him and shouted over the tumult, “Free ale tonight!”

He was right about that, too. Ale there was, and the best, in tall green glasses the landlord brought out from his wife’s own shelves. When Cade finally staggered upstairs to bed—oh, the delight of a real bed with a real mattress and real sheets, and all to himself besides—he had to work hard at it to remember how buttons and lacings worked as he got out of his clothes and slid between those real sheets, naked so he could fully enjoy them. He was asleep before he had time to do more than stretch in the luxurious little cocoon. For the second night in a row, he had no dreams. And when he woke in the morning, surprisingly free of a hangover, considering the amount of ale he’d drained down his throat the night before, he was actually happy.

Their ride home was in the back of one of Mieka’s aunt’s whiskey wagons. It was chilly, but it was free—and it became a lot less chilly when Mieka tugged the bung from a half-size barrel snugged in beneath the driver’s bench and handed out tin cups.

“She always puts this one in for me,” he said, patting the barrel fondly.

By the milestone that marked halfway home, all four of them were roaring drunk—or, rather, warbling drunk, because Jeska had issued a singing challenge for Most Obscene Ballad. The black sky overhead, dappled with stars, was treated to Rafe’s touching rendition of “Whistlecock and Biggerstaff” and Jeska’s contribution of “The Wizard’s Wondrous Wand.” Cade gave them a mercifully truncated version of the thirty-three stanza “What a Lady Needs,” mainly because he was too drunk to recall the middle fifteen requirements. But before Mieka could offer a contender, he passed out. By the Presence Lamps of a lonesome countryside chapel Cade saw him do it, marveling at the transition from full, laughing consciousness to absolute oblivion between one eyeblink and the next. He slumped against a barrel of whiskey, his jaw dropped open, and he began to snore. Jeska prodded him in the side with a toe of his boot; there was no reaction.

“Will somebody for the love of the Lord shut him up?” Rafe growled.

“Lay him down on his side,” said the driver, with a glance over his shoulder.

They tried, tugging and cursing, until Mieka grunted, pulled away, and—still sitting up, more or less—curled with his cheek to one of the padded crates containing Cade’s glass baskets and withies.

“He’ll sleep it off by daybreak,” the driver continued. “Now, tell me again, where am I setting you boys down?”

“He won’t be sick, will he?” Cade asked. He’d stitched the feather-filled cushioning himself, each nest specific to the basket it held.

“Never that I’ve seen it.” He paused for thought. “Always a first time, though.”

“Wonderful,” Cade muttered, and yanked the boy away from the padded crate with scant sympathy for any bruises he might be giving. Mieka grunted again, shifted, and this time curled on the floor of the wagon with his head on Cade’s knee. He snuffled like a puppy and settled back into sleep.

Jeska sniggered. “At least if he yarks, it’ll be on you.”

“I’m washable.” Shrugging, he addressed the back of the driver’s head. “Let them off at Beekbacks Lane.” Rafe lived a block north, Jeska four blocks east. “And me at Criddow Close, if you would.” He had all his baskets to carry, and his partners helped him when they took the public coach, but he was certain that Blye would be readying the glassworks by the time the wagon got them home, and be on the lookout for him—he was returning a day later than planned. That she would help him with the crates was secondary, though; he wanted her to get a look at his new glisker.

It was nearly daybreak, and the city traffic had not quite snarled the streets yet, when the wagon stopped at the top of Beekbacks Lane. Mieka didn’t stir as Jeska and Rafe jumped off. Cade threw their satchels down to them and reminded them of rehearsal at Rafe’s the following afternoon. The fettler’s parents were most obliging when it came to giving over their sitting room to their son and his friends. Jeska’s widowed mother allowed them the use of her cellar, but strictly in the summer months; she worried about the damp. Cade’s parents didn’t want that rubbish in their house at all. He wondered suddenly what sort of attitude Mieka’s family had towards his work, his ambitions, his determination to live the unpredictable life of a traveling player. As the horses began their weary clopping over the pavement again, he looked down at the head still resting on his knee. Shaggy black hair hid most of the face, and Cade was tempted to brush it back, wake him up, ask the thousand questions he should have been asking all day yesterday and all night last night. What held him back was the memory of another bit of advice from the Sage who had taught him.

“Sometimes, you know, it’s best just to let things happen. There are places and moments and people meant to be savored. You can force flowers to a quicker bloom in a hothouse, but they only fade all the faster. What your mind can do to you, Cayden, means that all too often you’re skipping ahead in a book to the last few pages, and you find out how it ends—but you have no idea how you got there, how it happened the way it did. In brief, there are times when you simply have to sit back, relax, and enjoy the show.”

The driver brought the horses to a halt at the bottom of Criddow Close, tucked up onto the cobbled footway to avoid carts and coaches now clogging the morning. The city had woken up; Mieka hadn’t. Cade stacked the crates handed down to him by the driver, who also did him the favor of yelling at a Trollwife as she prepared to slosh her slops bucket down to the drainage runnel right next to Cade’s feet. By the time the last of the gear was unloaded, Blye had been distracted from her kiln, as Cade had known she would be. She stood in the middle of the lane, absently smacking fireproof dragon-gut gloves again her thigh. He waved, and she tossed the gloves back into the shop and started towards him.

“Until another time then, lad,” the driver said. Cade nodded and began to express his gratitude, but he interrupted with, “Last night? I was watching. You’d do well to keep him, in spite of the trouble he’ll be to you.”

He would have asked how much trouble, and what kind, but Blye was beside him, cuffing him affectionately on the shoulder, and he smiled down at her. No one would ever know it to look at her, because the more obvious traits of the bloodline had been more or less overcome by Human and Wizard, Piksey and even some Elf, but like all those who worked with fire or forge, she was primarily of Goblin descent. It showed in how short she was, and her wiry build, and her slightly crooked teeth, but only if you were looking for Goblin traits. Her beauty was in the silvery blond hair that any other woman would have slit her own throat rather than cut; Blye kept it scythed off to barely neck length, to keep it out of her way when she worked. Cade hadn’t seen her in a skirt for any occasion other than Chapel since they were children. She was exactly five days older than he, and they had known each other all their lives.

“Yes,” he told her before she could say anything, “I made it home in one piece. Yes, I have the money you lent me for the trip, plus enough to take you out for a drink tonight. Yes, we were good, and he’s why.” He pointed to the slumbering Elf curled between whiskey barrels. “Introductions will have to wait for when he’s conscious, but that’s our new glisker.”

Placing a foot on a wheel spoke, she hoisted herself up to peer over the side of the wagon. “You’re hiring children now?”

“He’s eighteen. Well, probably. But it doesn’t matter, Blye, he’s good.” Then, shrewdly, knowing she’d be caught even if she didn’t want to admit it, he added, “He only wants to use your work from now on.”

“So I’ll be getting to know him whether I like it or not?” Blye looked for a moment more, then jumped down. “I’d better like it, Cade,” she warned. “Come on, let’s get your things inside and you can tell me all about it.”

They were arranging the crates between them with the ease of long practice, and the wagon had just set off again, when a voice rang out.

“Tell her she’ll adore me, Quill—everyone does!”

Blye slanted a look at Cade, dark eyes not quite amused. “Adorable, is he?”

“To hear him tell it.” He shrugged. “Me, I don’t much care what he says or does offstage. When he’s on…”

“Jeska and Rafe agree with you?”

“They agreed with me before I did!” They reached the back door of Cade’s parents’ house, and he paused. “We’ll be at the Downstreet tomorrow night, Blye, I wish you’d come and see.”

“P’rhaps I will. Is he really that good?”

Reluctant as he was to admit this, still he had never been anything less than honest with her. “Y’know, I think he might be better.”

Chapter 3

Time after time it happened, and every time it happened, it was different.

Sometimes there was a setting, just as if he’d planned it all out for a performance: a backdrop as clear and tangible as if he could walk into the room and pull the curtains open to the sunshine, or stride up the hill and feel the wind on his face as it rustled the trees. There were smells and sensations, he could hear chirring birds and mothers calling their children inside for supper. He even knew what clothes he wore by the feel of linen or wool or leather against his skin. He was there, in that place and time, and if he was lucky, a glance around would show him a broadsheet thrown on a table or left open across a chair arm, and a glimpse of its date would tell him precisely when he was.

But sometimes there were only vague shadows. Glimpses. Fleeting sensations. Unrecognized, unclear voices. Being a crafter of words, a designer of specific magic, he was both annoyed and frightened by the imprecision. He never knew if the blurred dreams were blurred because that particular future was as yet unresolved, unset, uncaused. He did know that the crisply real futures could be changed, in spite of their detailed authenticity, because he’d done it. He had done it when he was twelve years old.

{His mother turned her back on him and stepped lightly from the drawing room, the satisfied smile on her face seeming to linger in the mirror above the hearth. He felt Mistress Mirdley’s warm, powerful arms around his waist as she hugged him, but she let go very quickly and hurried for the kitchen. He thought she might be crying. He hoisted his satchel up onto a shoulder and turned, catching sight of himself in the huge gold-flecked mirror that had long since been drained of its magic. Very tall, very thin, the merest shadow of a beard on his jaw, he could not have been more than sixteen. His fist clenched around parchment, and he looked down at the letter with loathing.

Master Remey Honeycoil

Fine Imported Wines

72 Tullyhowe Lane

Vintners and Victuallers Guild

How pleased Master Honeycoil was to accept so clever a boy as his clerk—and how relieved his mother was that selling her son into servitude would cancel out the family’s liquor bills for the last two years and the next three besides. Shoving open the door to the vestibule, grabbing up his father’s old blue cloak, not pausing to don it against the snow-swirled night outside, he unlatched the front door and left his parents’ house for what he knew was the last time.}

It had all felt so real. So appallingly real. He’d woken, shivering as desperately as if he really had been outside in the bitterest cold, rather than sweating with the midsummer heat in his own bedroom high above Redpebble Square. But what had awakened him had not been the lingering chill of his dream. As he lay there, trying to catch his breath, he heard his mother cry out, and then the quick heavy stomping of Mistress Mirdley’s feet up the wrought iron staircase, and knew the baby was finally about to be born. Pillows over his head to muffle the awful sounds from two floors below, he reviewed the dream and concluded the obvious: that this new baby would be a boy, and healthy, and as good-looking as his handsome parents, and therefore Cade would no longer be required to enhance the family repute. But something would have to be done with him, something would have to be found for him to do with his life. When the bills came in for little Derien’s Namingday party a month later, he saw the note from Master Honeycoil, and chills shook him once again.

That he was not tending the wine shop at 72 Tullyhowe Lane was his own doing. It had not been as simple as stealing his father’s new blue woolen cloak and stuffing it into the glassworks kiln, although that was the very first thing he’d done. In retrospect, he was ashamed of himself for it. Not for stealing and destroying the cloak (a household mystery ever after), but for having panicked. One had to think these things through, he decided. So he thought, and found that it was even simpler than it had at first appeared, for what it all came down to was money. So for the rest of that summer and on into the autumn, he ran errands for the Trollwives who served the other houses in Redpebble Square, using the coins earned to pay Master Honeycoil on the sly. It wasn’t until the beginning of winter that he had his inspiration: to work for Master Honeycoil after school each day. During a month of sweeping floors and lugging crates, he learned quite a lot about wine—at secondhand, of course, being not quite thirteen years old. And then one day his employer mentioned that when the current apprentice went to open his own shop, another boy would be needed. So Cayden—who only the previous night had woken from a slightly different version of the same dreadful dream, still featuring his departure from home to become Master Honeycoil’s apprentice—made the “mistake” that cost him his job. A shipment of twenty-year-old wine to a very important client for a very important Wintering party in the Spillwater district somehow was switched with two dozen bottles of rumbullion lately arrived from the Islands. Master Honeycoil sacked him and refused to have anything to do with the Silversun household again.

There had been other dreams, of course, where he saw himself walking out the front door to become anything from an office clerk to a bookseller. (That wouldn’t have been too bad, but it wasn’t his choice any more than the wine shop.) There were also visions of being summarily thrown out the back door and slinking along to Blye’s or Rafe’s because he had nowhere else to go. As each dream occurred, he made plans to show himself incompetent at the proposed work, or to offend the master whose apprentice he might have become. It seemed to him that just thinking about how to avoid a particular future must change things enough to cancel those possibilities for all time. Yet it remained that he had done it, he had made certain that he would never be trapped into any life he didn’t want. Now, at nearly nineteen, he was what he had always yearned to be: a tregetour, an artist. And when he finally walked out his parents’ front door for good, it would be to lodgings of his own, paid for with his own money, and he would be answerable to no one and live exactly as he pleased.

But for the time being, he still slept in the smallest and highest of the bedrooms, and mostly avoided his family—though it had turned out that he and Derien liked each other. The little boy was old enough now to understand that he was the important one, not Cade, and it was beginning to be clear to him that the responsibility was a burden Cade was more than happy to surrender. It remained to be seen if Derien would choose to shoulder their parents’ hopes or shrug them aside. Cade thought it could go either way. He spent as much time with Derien as he could, bespelling silly voices into stuffed animals and creating Fae lights that danced to make him laugh. He liked Dery for his affectionate heart and inquisitive mind; but even if he hadn’t, Cade would have been benevolence personified to anybody who freed him of his parents’ ambitions.

Those ambitions were emphasized by their address. Criddow Close was the back entrance. Their front door opened on the infinitely more stylish Redpebble Square. It had been the pretty conceit of the long-dead nobleman who had ordered the town houses constructed to use dark red sandstone from his own quarries. He had, regrettably, started a trend; Gallantrybanks was here and there inflicted with buildings made of stone in shades of sunshine yellow, seaweed green, clover blue, and a frightful shade of orange. Any color other than white or gray made it easy to date a block of houses to that period. The Silversun residence was the smallest and narrowest on the Square, having originally housed a collection of upper servants who worked in the more lavish homes. Cade’s great-great-great-grandfather had purchased the five-floors-plus-attic house from the founding noble’s impoverished descendant, and by now Cade’s mother had almost everyone convinced that it had never been servants’ quarters at all, but the elegant little town mansion of the nobleman’s widowed mother. Not that anyone but Lady Jaspiela cared. Cade certainly didn’t. The tall, thin house had felt constricted to him ever since he could remember—as if it were a coat too tight in the shoulders, that wouldn’t allow him to stretch without ripping a seam. His mother glided with perfect composure up and down the delicate wrought iron staircase, serenely approving the tricks she had herself arranged—mirrors, pale walls, sparse but supremely elegant furniture—to make the rooms look bigger. All of it illusion, especially the big gilt-framed looking-glass over the hearth. Long ago that mirror had been the dwelling of no one quite knew who or what. But there was no magic left in it now.

The glassworks down Criddow Close had been established by Cade’s grandfather, a Master Fettler who had performed on the Royal Circuit. He had set up his favorite glasscrafter a few steps away from his own back door. This artisan had been Blye’s great-grandfather. The families got along splendidly until Cade’s father brought Lady Jaspiela home as his bride. Arrogant about her heritage, she had no time for anyone tainted by even a trace of Goblin blood. The Lord and Lady and all the Angels help anyone who failed to address her by her title—even though their title was all her family had retained after championing the losing side in the Archduke’s War. She had condescended to marry Cade’s father for two reasons: his descent from some long-ago princess nobody else cared about, and the fact that he was the only undamaged son of a wealthy Master Fettler with plenty of Court connections. She hadn’t counted on his being a shiftless quiddler who was forever promising the world … tomorrow. Or surely the day after. Perhaps next week. Certainly by the end of the month …

But he was charming and handsome, was Zekien Silversun, and she forgave him everything so long as he treated her with the deference that was her due, and called her Lady, and brought a few Court nobles to dine every so often.

Cade wondered sometimes if he was so good at what he did, at making up scenes and stories, because he’d inherited his mother’s gift for pretending.

At least he wasn’t self-delusional. Sagemaster Emmot had crushed that out of him by the time he turned fourteen. His parents, however, were of the opinion that Cade was deceiving himself about his life’s work. If so, he intended to go on deceiving himself—and everyone who saw his work—until the day he died.

But accompanying the Wizardly magic that he was positive would make his name and his fortune onstage was the bequest of the Fae within him. The dreams were not delusions. They were real. Worse, they might become real.

Blye always knew when the visions had come. When he met her at his parents’ back door the evening of his return from Gowerion, she saw it in his face at once. She said nothing, though, until they were well away from Criddow Close and walking up the cobbled slope of Beekbacks to the only tavern within a mile that allowed decent women inside—even the eccentric ones who wore trousers.

“What was it this time?” she asked quietly.

He shrugged.

“You looked tired this morning when you got home. You look about ready for the burn and the urn now. Did you get any rest this afternoon?”

“Not much.” That morning, he’d begged off telling her the tale of the last few days and gone up to his bed. He’d slept, but he hadn’t rested. Not at all.

“We don’t have to do this tonight,” she insisted. “Why don’t we go back to the works, and I’ll get out that bottle my da keeps for important customers? He won’t miss it,” she added bitterly. “Word’s got round. There aren’t many customers, important or otherwise.”

“You should have told me.” He detoured down a side street, nipped into a shop, and emerged a few minutes later with a distinctive long-necked bottle. “Colvado brandy,” he said. “I can afford it.”

“Because of the new glisker. I’ve been fretting myself to splinters all day,” she admitted as they retraced their steps back to the glassworks. “You have to tell me everything, Cade. Especially if I’m to be making all the withies from now on.”

He grinned down at her. “I knew you wouldn’t be able to stop thinking about that part of it! And he’s serious, he truly is. Picked out yours from your father’s without a single mistake. What’s more, he said that while he was working, he could sense how well you knew me from how they felt in his hands.”

“Hands?” She looked up sharply. “Both hands?”

“I know it’s odd,” he said. “But he does, he works with both. And doesn’t just sit there, either. It’s—it’s a dance, what he does. You have to come see us tomorrow night, Blye, you just have to.”

She unlocked the door of the glassworks and gestured him inside. “P’rhaps I will,” she allowed.

“I wish you’d let me spell that for you,” he said suddenly, gesturing to the lock. “So nobody but you and your father can get in.”

She shook her head. The silvery hair, loose from its band and neatly combed, shifted around her cheeks. “Beholden, Cade, but I can always feel additional magic, and it distracts me when I work.” She led him through to the little shop, and he made a casual gesture that lit the overhead lamp with a mellow bluish light: Wizardfire in its gentlest form. Shelf on shelf of vases, goblets, bowls, and baskets gleamed the full spectrum of colors. In a special display case atop a wooden plinth was a sampling of a full suite of tableware, plate to chalice to eggcup. Cade walked over to investigate.

“This is new,” he remarked. “Yours, right?”

“Some of it,” she admitted. “As much of each piece as the Guild allows, so we can legally sell it with Da’s hallmark. But it’s my design.”

“It looks like you,” he said. When he saw her brows arch, he smiled. “Silver and gold round the edges, dark accents. Unpretentious. And threatening to become elegant any moment now.”

“Elegant!” Blye snorted. “Lady forefend! Open the bottle and tell me about the glisker.” From the assortment on the shelves she selected a pair of round-bellied snifters swirled with green, eyeing him sidelong as she appended shrewdly, “Or maybe I should say, tell me the dream you had today that was about the glisker.”

He supposed it was a measure of how much he’d learned while bargaining with tavern keepers that not a flicker of reaction crossed his face. As Blye held out the glasses, he was ashamed of himself. Of all the people in his life—including Rafe and Jeska and even Mistress Mirdley—he trusted Blye alone with most of himself. Most; not all.

“I know you remember it,” she went on sympathetically. “Sage Emmot taught you how to remember every single detail. If you don’t want to talk about it, fine. But you did dream today.”

He poured brandy, set the bottle aside, and cradled the glass in his hands to warm the liquor. “I’m not sure I want to talk about it yet. But wait till you hear what happened in Gowerion.”

He talked, she listened, and they got through half the bottle. Yet even as he described what Mieka had done, and how the audiences had reacted, the boundary line separating his waking mind from the insistent dreaming began to smudge. Yes, he remembered it; all of it; Sage Emmot had taught him so well that he could never not remember.

{Perhaps the tavern had once been fashionable and popular. Not anymore. The chairs were rickety, the tables stained and scarred. Instead of fragrant wood in the huge hearth, finances compelled the burning of turfs, and not very good ones at that. The stink was unmistakable.

Over in a back corner two men sat opposite each other, leather tankards between them. One man stared into his ale; the other stared with calculating intent, paper and pen and ink at the ready.

The first man spoke, his voice raspy, one hand suddenly raking lank brown hair from his face, fingers shaking a little. “I must’ve written a dozen pieces about them through the years. I don’t think anybody ever realized how good they really were.” He drained his ale down his throat, coughed, wiped his mouth with his sleeve, and glanced at his companion.

The hint was not taken. The second man smiled blandly and rendered ink onto paper with a delicacy unsuspected in such thick fingers. “You said you first met them after their rather sensational appearance at Trials.”

“I didn’t see the performance, but I knew somebody who did, and he tipped me that they might be something very special. They were, of course. But no one ever really understood until he was gone.”

“Did they ever admit to it?”

“Rafcadion came closest, two or three years ago. Said he missed him.” He reached over and appropriated the other man’s ale, took a swig. “But a week or two later, he gave another interview saying he didn’t miss him at all, when it came to the performing. As a friend, yes. Not as an artist, a partner onstage.”

“He was lying,” the other man suggested.

“Oh, yes. Jeschenar’s never said anything about him at all, but I’ve spoken with Cayden a few times since it happened.”

“And—?”

“Full of himself, he is. The meaning of this and the significance of that, what art must do and artists must be in society, all sorts of bilge. But he’s a cold unfeeling bastard and it’s no wonder his wife finally left him.”

“Unfeeling? Forgive me, Tobalt, but—”

“I know. He emotes all over everything, doesn’t he, in his work. But the only feelings that matter are his, you see. It’s only important if he feels it—and he expects unconditional compassion that he’s feeling that way. Not that he expects understanding, because nobody could possibly understand him, he’s unique, and an artist, and all that rot. And he’d never let anyone help him find his way out of whatever mood he happens to be wallowing in.” Tobalt leaned forward. “What isn’t readily obvious in the work is that although he does feel these things right enough, he also stands apart from them so he can slice them up like feast-day mutton and then use them. His mind’s cold, but his heart’s colder.”

“He wasn’t always like that, was he?”

The rest of the ale was swallowed, the tankard slammed down onto the table. “He has to be that way, now. Got no choice, has he? He’d go mad, otherwise. Because he knows. He’ll never admit it, but he knows. When the Cornerstones lost their Elf, they lost their soul.”}

“Cade.”

The snifter almost dropped from his hand. Blye was looking at him as if she’d been looking at him for quite some time—waiting for him to rouse from whatever vision was playing itself out inside his head. “Sorry,” he muttered.

“Stop apologizing! I’m not your mother.” She held out her near-empty glass. “Might as well finish it.”

He thoroughly agreed. They sat quietly for a time, sipping fine liquor that tasted of oak and golden apples. At last he made an effort. “How’s your da? You haven’t said.”

“No better, no worse. He got in a few hours of work today, actually.”

“Anything usable?” He regretted the words as soon as he spoke them. Her dark eyes flashed angrily, and then her face became a mask quite as good as any he’d ever worn himself, or magicked into a withie for Jeska to wear. But he knew better than to apologize again; she’d only snap at him again. Instead, he asked, “Want something to eat? Mistress Mirdley was making dumplings earlier.”

“No, I’m fine. I know better than to drink on an empty stomach—which is more than can be said for you.”

“I’ve had practice. Say you’ll come tomorrow night.”

“So I can meet him and adore him?”

The image of the Elf came into his head. He flinched. Their soul, the man had said, he had been their soul, and when they’d lost him—