By Ariana Carpentieri:

By Ariana Carpentieri:

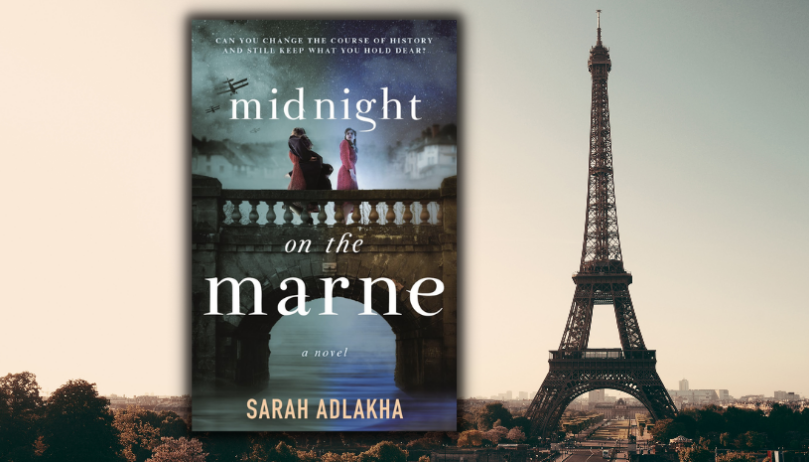

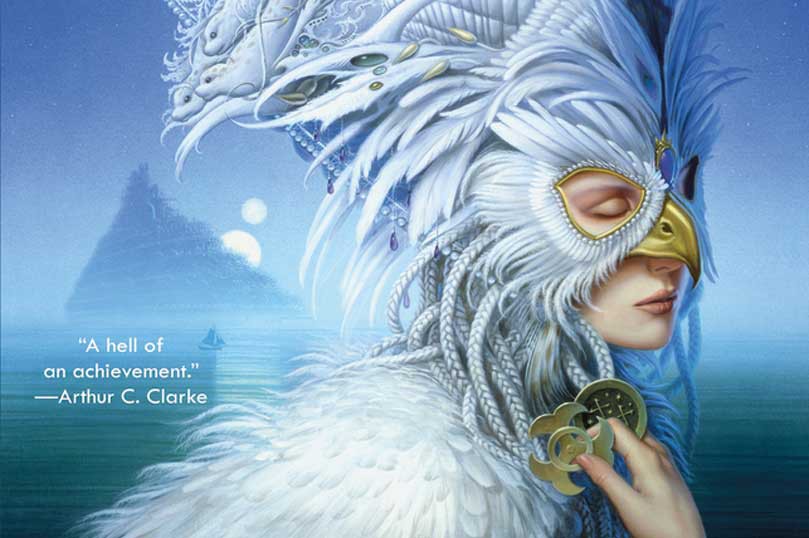

France, 1918. Nurse Marcelle Marchand has important secrets to keep. Her role as a spy has made her both feared and revered, but it has also put her in extreme danger from the approaching German army.

American soldier George Mountcastle feels an instant connection to the young nurse. But in times of war, love must wait. Soon, George and his best friend Philip are fighting for their lives during the Second Battle of the Marne, where George prevents Philip from a daring act that might have won the battle at the cost of his own life.

On the run from a victorious Germany, George and Marcelle begin a new life with Philip and Marcelle’s twin sister, Rosalie, in a brutally occupied France. Together, this self-made family navigates oppression, near starvation, and unfathomable loss, finding love and joy in unexpected moments.

Years pass, and tragedy strikes, sending George on a course that could change the past and rewrite history. Playing with time is a tricky thing. If he chooses to alter history, he will surely change his own future—and perhaps not for the better.

Time plays a big role in this story. So in honor of the trade paperback release of Midnight on the Marne, here’s a list of 5 timeless locations to visit if you find yourself wanting to get lost in France!

The Louvre

The Louvre, or the Louvre Museum, is a national art museum in Paris, France. A central landmark of the city, it is located on the Right Bank of the Seine in the city’s 1st arrondissement and home to some of the most canonical works of Western art, including the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo

Vedettes de Paris Seine Cruise

Glide by the famous sights of Paris on a relaxing sightseeing cruise down the Seine River. Vedettes de Paris offers the most original tour cruises on the Seine, starting just minutes away from the Eiffel Tower and runs nearly every day of the year.

Palace Of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, which is about 12 miles west of Paris. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, under the direction of the French Ministry of Culture, by the Public Establishment of the Palace, Museum and National Estate of Versailles. About 15,000,000 people visit the palace, park, or gardens of Versailles every year, making it one of the most popular tourist attractions in the world.

Mont Saint-Michel

A magical island topped by a gravity-defying abbey, the Mont-Saint-Michel and its Bay count among France’s most stunning sights. It’s one of Europe’s most unforgettable sights. Set in a mesmerizing bay shared by Normandy and Brittany, the mount draws the eye from a great distance.

The Eiffel Tower

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/eiffel-tower-paris-france-EIFFEL0217-6ccc3553e98946f18c893018d5b42bde.jpg)

And last, but certainly not least, the pièce de résistance: The Eiffel Tower. One of the most iconic locations in the world, The Eiffel Tower is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower. Locally nicknamed “La dame de fer,” it was constructed from 1887 to 1889 as the centerpiece of the 1889 World’s Fair.

Click below to pre-order your trade paperback copy of Midnight on the Marne, coming July 4th, 2023!