opens in a new window

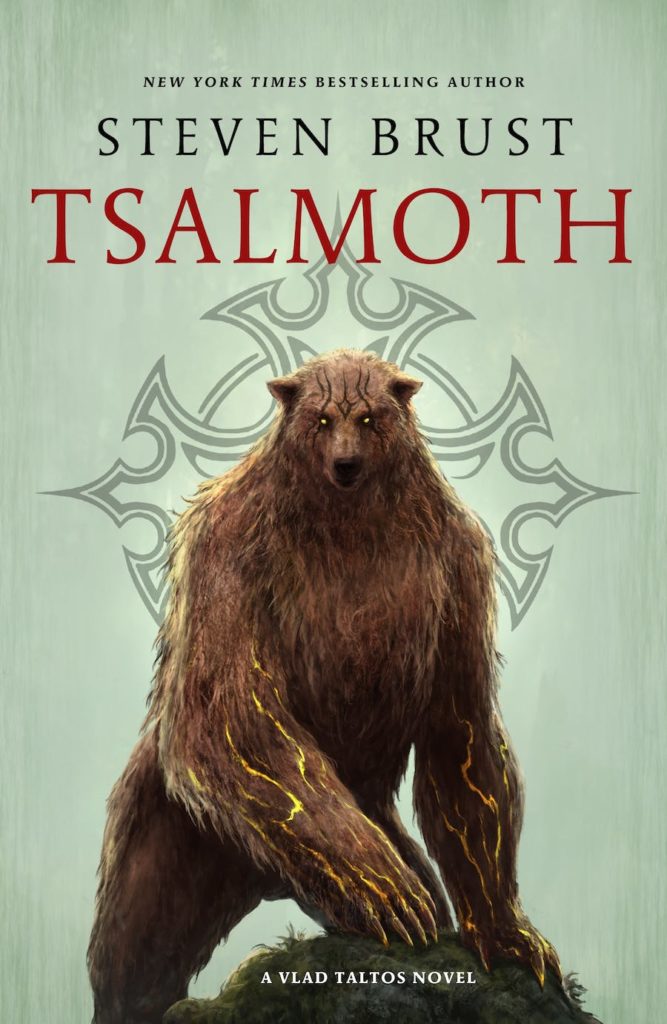

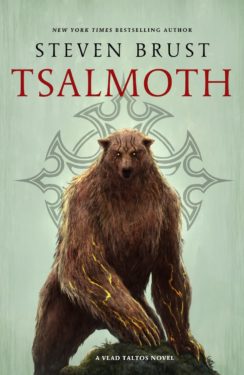

opens in a new windowTsalmoth is the next installment in Steven Brust’s bestselling Vlad Taltos series—hold on to your hats and get ready for another swashbuckling adventure!

First comes love. Then comes marriage…

Vlad Taltos is in love. With a former assassin who may just be better than he is at the Game. Women like this don’t come along every day and no way is he passing up a sure bet.

So a wedding is being planned. Along with a shady deal gone wrong and a dead man who owes Vlad money. Setting up the first and trying to deal with the second is bad enough. And then bigger powers decide that Vlad is the perfect patsy to shake the power structure of the kingdom.

More’s the pity that his soul is sent walkabout to do it.

How might Vlad get his soul back and have any shot at a happy ending? Well, there’s the tale…

Please enjoy this free excerpt of opens in a new windowTsalmoth by Steven Brust, on sale 4/25/23.

1

There are problems that just can’t be solved by sticking something pointy into someone. I try to stay away from those kinds of problems, because they get complicated, and I don’t like complicated. I’m a simple guy. Ask anyone. “That Vlad,” they all say. “He’s a simple guy.”

“Hey Kragar,” I called out to the next room. “I’m a simple guy, right?”

I heard footsteps, and he stuck his head into my office. “What?”

I repeated my question.

His eyebrows did funny Kragar-things, and he came in and sat down across from my desk. “What happened?”

“Why should something have happened?”

He just waited.

I said, “You know that Tsalmoth who went into us for eight and scampered?”

“Bereth. Sure, I put Sticks on it.”

“Yeah, Sticks just got back to me.”

“And he found him, and got the money, and broke his legs, and everything is fine now, right?”

“Heh,” I explained. “Someone killed the son of a bitch.”

“Need an address to send flowers?”

“No, I need a way to get my Verra-be-damned money.”

“Hmmm. Tricky.”

“I know,” I said. “Tricky. And I’m a simple guy.”

“Can he be revivified? We could add the cost on to what he owes us.”

“Sticks says no.”

“In that case, Vlad, I would suggest a clever strategy: write off the money.”

I felt myself scowling.

“It’s not tricky,” he added, with his fake innocent smile.

My familiar, Loiosh, arrived in the window about that time, flew over, and landed on my shoulder.

“What’s going on, Boss?” he said into my mind.

“Nothing, nothing.”

He let it drop.

I said to Kragar— Wait a minute.

Sethra, Why are you still here? Last time you put me in a room with this box and just left.

Wait, Seriously? You think you can help? But before, you told me—

No, no! I’ll take a maybe. Maybe is good. If you can give me a maybe, I’m happy to tell you the whole mess. Get comfortable. Can I get you some wine?

Right. I won’t count on anything, I’ll just tell it. Only, uh, what happens when you come into it? I mean, do I say, “You did this?” which won’t make sense to whoever is going to listen to this, or do I say, “Sethra did this,” which is dumb with you sitting there?

Oh, yeah, Sethra. It’s so easy to just pretend you don’t exist. Heh.

Okay, okay. Where was I? Right. Talking to Kragar. He’d made that remark about, hey, it’s not tricky. I said to him, “You see, you might not know this, but I don’t like letting money get away. It makes me feel bad.”

“Uh huh,” he said.

“So, come up with something.”

“How,” he said, “did I know this was going to end up on my back?”

“On account of that, what’s it called? Wisdom.”

“Fatalism,” said Kragar.

I shrugged. “Let me know what you get.”

He left, muttering under his breath. I leaned back and closed my eyes. I checked my link with the Imperial Orb and did deep and powerful sorcery, which it was designed for. Just kidding, I usually leave the deep and powerful sorcery to those who are better at it; I used it to find out what time it was, and discovered that I had a couple of hours to wait until it was time to meet Cawti.

“Aw, Boss,” said Loiosh. “Do you know that every time you think about her—”

“You can shut up now,” I said.

While I waited, maybe I should tell you a bit about myself.

Nah, skip it. That’s boring. You’ll figure it out.

There was a street singer not far from my window, singing something in a language I didn’t know—probably one of the classic disused tongues of the early Empire. I hate listening to songs when I don’t know the words.

I still had a few minutes before I felt justified in leaving for the day to meet Cawti when she jumped the bell on me by coming in.

I was up out of the chair in a second, standing there grinning like a Teckla smoking dreamgrass.

Look, I’m telling you what happened, including it all, because that’s what you paid for, so there it is. I probably looked like an idiot with that big grin all over my face, so go ahead and laugh. But if you do, I’ll track you down and break both your kneecaps, got it?

Uh, I didn’t mean you, Sethra. I meant, you know, whoever is going to listen to this.

Right. You aren’t here.

All right, so I kissed her, which is as much as you need to know, and then we went out and did some stuff together. We ate and drank and laughed and all that. It was a good time. I asked about Norathar, her partner, or I guess ex-partner, and they’d been in touch, which was good. Then we had an argument about the best kind of pasta to serve with clams and promised to settle it by each doing our own recipe. Then we went home to her flat. She lives a good distance south of me, in a decent neighborhood where she’s the only Easterner but where you can smell the ocean-sea, which she likes. And her flat, like mine, has its own kitchen. I mean, a real kitchen, with a stove, an oven, a sink with a pump, cupboards, and countertops. So we hung out there, and decided to find a place in South Adrilankha to have the wedding, and then we did what you do when two people can’t keep their hands off each other.

Look, I’m not bragging, I’m just saying how it was, and that feeling that she wanted me was—

Crap, this is hard to talk about with you here, Sethra, and no one’s business anyway.

Back to what matters, I finally got around to telling her about the guy who’d had the nerve to go and die when he owed me money.

“Some people,” she said.

“I know. Thoughtless.”

She stretched like a cat, which made me stupidly proud, as if I’d accomplished something. She put her head on my shoulder and said, “Mmmm. What about his family?”

“Maybe,” I said. “I should find out.”

She wrapped her leg around me and said, “Maybe.” Who can argue with logic like that?

So that’s how I decided to check out the guy’s family. I still don’t think it was that bad an idea, okay? It’s not like I have the Dragon treasury; I need the money. And also, once word gets out that people can get away with not paying you, it’s gonna keep happening, and eventually you get put out of business. You know, in the big steel thing in your neck way of being put out of business. Not my favorite idea. This time, what with the guy dying, chances are no one would have thought anything except bad luck, but I’m still new at this, so I’m not sure and didn’t want to take chances. And I wanted my Verra-be-damned money.

I’m just saying this so you’ll understand.

Oh, I know. Now you’re saying, “He’s going after a bunch of innocents, heartless bastard, blah blah blah.” That’s not how it is, that’s not how it was ever going to be. I wanted to see if there was a way to do it clean and easy. I was not going to walk in and start making threats or doing violence to his kids or his grandparents or whatever. For one thing, well, maybe for the only thing, as soon as you cross that line and start messing with families, or with people who aren’t involved in the organization, the Phoenix Guard stop being these friendly sorts who greet you with their palms out for their weekly payoff, and turn into mean sons-of-bitches with all sorts of sharp things and no sense of congeniality. And because of that, even if word never reaches the Empire, if the Jhereg thinks you’re doing something that might get the Empire involved, then you will end up with a leaky body and a shiny skin. So I don’t do that. All I figured on doing was finding out if there were any loose funds there that might be subject to friendly persuasion, by which I mean, this time, friendly persuasion. Sometimes you go up to a grieving widow and say, “Sorry for your loss, but he owed me money,” and that’s all it takes. I had no intention of pushing it any further than that. I didn’t. I swear by Verra’s extra finger joint I didn’t.

The next morning, I told Kragar to find out what he could about the family, which is one of the things Kragar is good at. Some of the other things he’s good at are reminding me of unpleasant things I’ve agreed to do, unintentionally sneaking up on me, and being irritating.

He said, “Don’t you want me to tell you what I’ve come up with?”

“Sure. What have you come up with?”

“Check into his family.”

“Good thinking.”

“Thanks.”

“Get on that, then.”

“Already did.”

“I suppose you expect a compliment.”

“And a bonus.”

“Good work.”

“Thanks. The bonus?”

“Very good work.”

“Nice.”

“Let’s hear about them.”

He didn’t use notes or anything this time. “Survived by a younger brother, has a fabric shop not far from here, just north of Malak Circle. Unmarried, an occasional lover, a Chreotha named Symik, nothing serious between them though. Parents are both alive, living in Cargo Point, in Guinchen, where they run an inn called Lakeview.”

“Financials?”

“Hard to be sure, Vlad. The inn supports them, but not much more, and there’s no signs of wealth. I guess the brother is doing a bit better than the others.”

“Then I’ll talk to him. Get me his exact addr—Thanks.”

Kragar smirked and walked out.

Well, I figured, no time like the present. I stood up, strapped on my blade, and checked the various surprises I keep concealed about my person. Not long before, I wouldn’t have left the place without at least two, more likely four bodyguards, but things had quieted down now. That was good, I like quiet. I like things quiet, and simple. Did I mention I’m a simple guy?

So, yeah, a quick stop in front of the mirror to make sure my cloak was hanging right, and off I went. I keep meaning to practice putting on the cloak, you know, with a kind of swirl, like they do in the theater, but I never seem to get around to it, and I don’t think the ones in the theater are packed with as much hardware as mine, so it might not be possible. But, hey, since I’m talking about it, let me tell you about my cloak. I love my cloak. It’s Jhereg gray, ankle length, and looks good thrown over my shoulder or wrapped around, and it has inside pockets and seams to put things in, and a wide collar for more things to go under. And it looks very good on me; I know because Cawti said so.

Loiosh landed on my shoulder (he says the cloak makes my shoulder less bony, so that’s also a plus), and the three of us—me, Loiosh, and my cloak—took a walk through the beautiful streets of Adrilankha. The bright blue and yellow and green clothes of the Teckla were most common, even if a lot of them had become dingy or gotten stained, but there were merchants we walked past as well, and now and then you might catch sight of a Dragonlord or a Tiassa who had business in this part of town.

Malak Circle is built around a fountain, with stalls and carts about the outer edge and streets and alleys shooting off from it. I don’t know what magic is used to make the water shoot out from the mouths of the stone dragon and dzur into the cupped hands of the woman in the middle, or how more water sprays in from the sides, or where any of the water goes, but I know I like it, and sometimes I just stand there and watch the water. Not many do that.

There are Teckla in the area, most of them in service, running errands for the more successful merchants or the occasional aristocrat. For the Teckla, just like for the Easterners who live across the river, survival depends on two things: doing what they’re told, and never slowing down. They don’t have time to stop and look at the sparkling water. I don’t blame them for it, it’s just the stones they have to play with.

There are merchants around the edge, with carts or stalls: Chreotha, Tsalmoth, Jhegaala. They’re much better off than the Teckla, as long as they keep coins coming in and goods going out; if they don’t, they can fall even lower than the Teckla, out the bottom, living on scraps and stealing from each other in the Mudtown district, or parts of Little Deathgate. They always know that could happen, and it scares them like Morganti weapons scare me. Talk to one of them sometime. Ask one of them about courtball, and he’ll tell you how much sales are better if some local team wins. Ask about the weather, and you’ll hear how they can’t sell anything when it rains. Ask about rumors of war, and you’ll hear about how those rumors make customers stock up on some things and stop buying others. It’s always buy and sell, sell and buy, supplying what customers want, and never slowing down to watch the fountain. I don’t blame them for it; they, too, have the stones they were given and have to play them as best they can.

The merchants are supplied by the craftsmen: also Chreotha, Tsalmoth, and Jhegaala, and they, too, know what will happen if no one wants to buy what they make, or if someone can make it cheaper, or better. They have to keep the merchants happy the way the merchants have to keep the customers happy. Maybe they aren’t told what to do in so many words, but they’re told, and they listen, and they don’t stop to watch the water because they don’t have time, and I don’t blame them either, it’s just how the game works.

Once in a while, you’ll see one of the aristocrats: a Dragon, a Dzur, a Tiassa noble, an Iorich, a Hawk, an Orca, an Athyra; but even if you put all of them together, there aren’t many of them, and even most of those can’t support themselves as landlords, so Orca end up on ships, Dragonlords and Dzur in military service, Tiassa as writers or artists, Iorich as advocates, Athyra and Hawks as sorcerers. And all of those might as well be merchants or craftsmen, because someone is telling them what to do, and they’re doing it, and if they do it too slow, they, too, will fall out of the bottom, because wishing won’t turn a round stone into a flat one.

That’s what I can do. I can slow down. I got my income, and my skills to fall back on. If I want more, I can work harder; if I want to take it easy, I can do that too. Yeah, I’m beholden to my boss, but most of the time, I just do what I feel like, just like the landlords, and no one tells me what to do.

That’s why the Phoenix Guards hate me, and why some of those I passed in the market who saw my Jhereg colors hated me; I could do what they couldn’t. And, worst of all, I was an Easterner—you know, human: short, short-lived, weak; Easterners were supposed to be the next step down from Teckla, and stay there; Easterners should do what they’re told, and be quiet, and never slow down.

Some of those I passed knew who I was and what I could do. There are a good number of those in my neighborhood, and in the middle of the day, when the market is busy, they mostly stay out of my way. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t get some pleasure out of that. But I got even more pleasure in knowing that no one could tell me what to do, and that I could slow down when I wanted. Because there’s one thing we in the organization have in common: we don’t like being pushed. People know better than to push us.

Today, I wanted to visit Bereth’s brother, but I stopped for a bit on the way there to watch the fountain in the middle of Malak Circle, because I felt like it.

Copyright © 2023 from Steven Brust

by Daniel M. Ford — $2.99

by Daniel M. Ford — $2.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Cixin Liu — $2.99

by Cixin Liu — $2.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson — $2.99

by Brian Herbert & Kevin J. Anderson — $2.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Steven Brust — $2.99

by Steven Brust — $2.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Ian C. Esslemont — $2.99

by Ian C. Esslemont — $2.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

by Douglas Preston — $2.99

by Douglas Preston — $2.99 opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

King Rat

King Rat

Furious Heaven

Furious Heaven

Red Team Blues

Red Team Blues Tsalmoth

Tsalmoth Spring’s Arcana

Spring’s Arcana

Dual Memory

Dual Memory