opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

opens in a new window

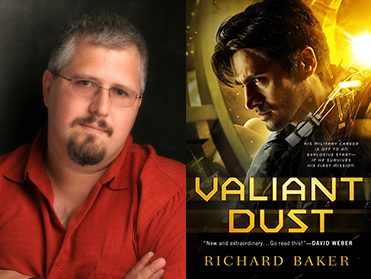

In a stylish, smart, new military science fiction series, Richard Baker begins the adventures of Sikander North in an era of great interstellar colonial powers. Valiant Dust combines the intrigues of interstellar colonial diplomacy with explosive military action.

Sikander Singh North has always had it easy—until he joined the crew of the Aquilan Commonwealth starship CSS Hector. As the ship’s new gunnery officer and only Kashmiri, he must constantly prove himself better than his Aquilan crewmates, even if he has to use his fists. When the Hector is called to help with a planetary uprising, he’ll have to earn his unit’s respect, find who’s arming the rebels, and deal with the headstrong daughter of the colonial ruler—all while dodging bullets.

Sikander’s military career is off to an explosive start—but only if he and CSS Hector can survive his first mission.

opens in a new windowValiant Dust will become available November 7th. Please enjoy this excerpt.

ONE: New Perth, Caledonia System

Lieutenant Sikander Singh North leaned forward in the shuttle’s right-hand seat, eager to catch his first glimpse of the light cruiser Hector. The shuttle climbed slowly into low orbit, only four hundred kilometers above the feathered white cloud tops and gray-green dayside of New Perth. The white glare of Caledonia’s sun illuminated dozens of freighters and tugs going about their business in the planet’s busy approaches. Sikander quickly spotted the huge mass of New Perth Fleet Base—hard to miss, really, since the orbital structure was the size of a small city—and narrowed his eyes, peering in turn at each of the ships moored to the station’s long arms. To his disappointment, the hulls of the Aquilan warships all looked the same at this distance; he felt he should have been able to spot his new ship as easily as he might pick out a pretty girl’s face from a crowd. He’d certainly spent enough time memorizing every detail of CSS Hector’s lines and armament over the month and a half since he’d received his new assignment.

Beside him Petty Officer Second Class Robert Long, a pilot in Hector’s Flight Department, smiled. He’d guessed exactly what Sikander was doing, and he pointed out the docked cruiser for him. “Left-hand side of Fleet Base, sir, the second berth from the top. We’ll be there in just a minute.”

“Thank you,” Sikander replied. He looked where the pilot pointed, and there was the Aquilan Commonwealth starship Hector, hull number CL 88. She was not the newest or largest of the ships moored at New Perth’s orbital dock, but she was a handsome vessel nonetheless. He tapped the visual controls for the shuttle’s viewports and zoomed in for a good look. Two hundred and sixty meters long, the Ilium-class cruiser (so called because all of her sisters were named for Trojan heroes from Homer’s ancient epic, or so Sikander had read) had a graceful teardrop-shaped hull and powerful drive plates in sleek fairings aft. Her deadly kinetic cannons were housed in large, dome-like turrets that dotted her spine and keel, and the round ports ringing her bow concealed her potent torpedo battery. Hector might have been nothing remarkable by Aquilan standards, but she would have been the most powerful warship several times over in Sikander’s native system of Kashmir, and it would be at least another generation before his homeworld could build a ship to match her.

“The Old Worthy’s a fine-looking ship, isn’t she?” Long observed. “Captain Markham is a stickler for appearances. She isn’t happy unless the paint’s still wet somewhere on the hull. But that’s the way it ought to be.”

Sikander agreed with the sentiment. If Hector’s captain took pride in her ship and wanted everyone to know it, he wouldn’t argue. Of course, the Commonwealth Navy didn’t actually use real paint on their warships, or at least not the sort that went on wet and dried into a coat; it was more of a nanoengineered polymer designed to stand up to the rigors of vacuum while displaying a handsome color scheme. Some star navies, such as the Dremish or the Nyeirans, favored all-black paint that made them a bit harder to spot with visual detectors, but stealth was generally pointless in normal space;simple physics dictated that ships couldn’t hide their heat signatures. The Aquilans recognized that and chose colors designed to evoke a little institutional pride from their ships’ crews. Accordingly, CSS Hector boasted a gleaming white hull, with buff-colored upperworks and beautiful red piping around the bow and the drive plates.

The shuttle continued its approach, while Hector seemed to swell up to fill the cockpit’s viewports. Sikander dialed back the viewport magnification, and leaned over to call down to the shuttle’s passenger area. “Come have a look, Darvesh,” he called. “We have a few minutes yet before we dock.”

“I am certain I shall see enough of Hector over the next two years, sir,” Darvesh Reza replied in a carefully neutral tone. He generally disapproved of the fact that Sikander continued to serve in Aquila’s star navy instead of returning to Kashmir to assume the proper duties of a North. Despite his reservations, the valet unbuckled his restraints and came forward to the cockpit, ducking through the low hatchway and steadying himself with a hand on the back of Sikander’s seat. In deference to the requirement of being able to don a helmet in case of catastrophe, the tall Kashmiri wore a small round pakul instead of his customary turban. Darvesh functioned as Sikander’s security detail, secretary, and general minder as well as his body servant. The impassive valet’s eyes widened just a little as he took in the size and lethal beauty of the Aquilan cruiser.

“Impressive,” Darvesh admitted. “And she is only a light cruiser?”

“Still three times the size of anything we can build back home,” said Sikander. The Commonwealth of Aquila was a first-rate power, by some measures the foremost among the multisystem states that formed the core membership of the Coalition of Humanity. Decades or centuries ahead in technology and industrial capacity, the great powers far outclassed single-system backwaters, even populous and economically valuable ones such as Kashmir. Sikander’s home system was merely a client state—or a colonial possession, more accurately—to Aquila. Building a fleet of large, modern warships remained out of reach for Sikander’s people, but he hoped to change that someday. Until then, he wore an Aquilan uniform.

Darvesh merely nodded in reply. As a younger man he had served in a Kashmiri regiment of the Commonwealth Marine Corps; he was accustomed to displays of Aquilan power. He glanced at the shuttle pilot. “Did you call Hector ‘Old Worthy,’ Petty Officer Long? That seems a strange nickname.”

“It is,” Long agreed. “I understand that it’s a reference to the ancient Earth hero Hector, the one who fought in the Trojan War. There have been a lot of ships—spacegoing and the old seagoing sort—named after him over the centuries. But I never have heard how that got turned into ‘Old Worthy.’ ”

“It’s a reference to medieval chivalry,” said Sikander. “Hector was considered one of the Nine Worthies, heroes that young knights should strive to emulate. Except the part about getting slaughtered by Achilles, anyway.” The Aquilans might have been a hundred years ahead of Kashmir in shipbuilding, but it seemed that he’d received a better education in the classics than his Commonwealth shipmates. Of course, very little about Sikander’s upbringing had been normal. Even by Aquilan standards the Norths were extremely wealthy, an aristocratic clan who could afford to buy their sons and daughters opportunities most Kashmiris could only dream of—for example, appointment to Aquila’s prestigious naval academy and an officer’s commission upon graduation.

Long shook his head. “Huh. That’s the best answer I’ve heard yet, and I’ve been on the ship for a year and a half. Can’t wait to try it out on the fellows in the ready room. They—” He broke off as the comm unit came to life.

“Shuttle Hector-Alpha, New Perth Traffic Control,” the audio crackled. “You are cleared for final approach and recovery on parent deck, over.”

The pilot nodded, even though this was only an audio link. “New Perth, this is Hector-Alpha. Clear for approach and recovery, roger, out.”

“Better go take your seat, Darvesh,” Sikander told his valet. A routine shuttle landing on a stationary dock was probably going to be about as rough as an elevator ride, but procedures were procedures, and passengers were supposed to strap down during departure and landing. For that matter, he was supposed to be ready to back up the pilot since he was riding in the copilot’s seat. This was Long’s boat and Sikander wouldn’t touch the controls unless the petty officer invited him to, but like any Aquilan line officer he was rated for ordinary shuttle operations.

Darvesh nodded and returned to the passenger seating, buckling himself in. Sikander adjusted his own restraints and sat back in his seat, watching as Long expertly adjusted the shuttle’s course and yawed the small vessel into a dead-center approach. Hector’s hangar was located in the middle of the ship’s “belly,” although that was mostly an illusion created by the customary Aquilian color scheme; there was very little real difference in what part of a warship was considered up or down. The large hangar door rolled open slowly with a puff of escaping atmosphere as the shuttle glided closer. No matter how many times a big compartment like a hangar deck cycled, traces of air remained to turn into a silver dusting of snow and drift out into the night.

Sikander watched carefully, but Long handled the shuttle with a masterly touch. He brought the boat into its cradle and set it down with a bump so gentle it wouldn’t have spilled a glass of water. “There you go, Lieutenant North,” he said. “Welcome aboard! Wait for the indicator to turn green before you crack the hatch, please.”

“Thanks for the ride, Long,” Sikander replied. He unstrapped himself and straightened up, tugging at his flight suit and stretching carefully in the cockpit. He was not particularly tall, standing five or six centimeters shorter than most Aquilans he met, but he was wide through the shoulders and solidly built. The gravity of Jaipur, his homeworld, was a little higher than one standard, and over centuries natural selection had left most Jaipuri with stocky frames. Cramped spaces like a shuttle cockpit had a way of finding his elbows and shoulders if he wasn’t careful.

He ducked back into the passenger compartment, seized one of his own duffel bags despite Darvesh’s disapproving look, and waited for the atmosphere indicator by the shuttle’s hatch to go from red to green. No doubt the Kashmiri servant thought it undignified for Sikander to carry his own luggage, but Sikander had learned it was necessary to show his Aquilan comrades that he didn’t think he deserved any special treatment. No other officer on board besides the captain would have a personal attendant, after all, so the less he relied on Darvesh Reza, the better.

The light by the hatch turned green, indicating that the hangar bay was repressurized. Sikander cycled the hatch and stepped onto the hangar deck of the Commonwealth starship Hector for the first time. He turned and saluted the Aquilan flag displayed at the end of the hangar bay, then faced the watch officer in the hangar’s control booth. “Lieutenant Sikander North reporting under orders,” he said. “Request permission to come aboard.”

The watch officer returned his salute behind the booth’s wide viewport and answered through the intercom. “Come aboard, sir.”

Sikander waited a moment for Darvesh to complete the time-honored ritual of boarding a warship—for purposes of Aquilan naval etiquette, he’d been assigned an acting rank of chief petty officer—while the watchstander, a first-class petty officer, stepped out of the hangar control station and logged in their datacards. If the rating was surprised by Sikander’s identity, he didn’t show it. He simply nodded and said, “You’re expected, sir. The captain left word that you’re to call on her as soon as you get settled.”

“Very well,” Sikander replied.

“If you’ll follow Deckhand Parris, she can show you to your stateroom and give you a hand with your gear,” the watch officer continued. “After that, you can signal the ship’s info assistant to find anything you need—you’re logged in to the system now. Chief Reza, I’ll call for a messenger to give you a hand to the chiefs’ quarters.”

“No need,” Darvesh replied. “I will accompany Mr. North to his quarters first.”

The watch officer raised an eyebrow—he probably didn’t see many chief petty officers toting officers’ duffels—but made no comment. “Very good. Mr. North, Chief Reza, welcome aboard.”

“Right this way, sir.” Deckhand Parris was a short young woman who probably wasn’t more than twenty standard years of age. She smiled broadly at Sikander and Darvesh, and seemed to grin even wider as she tried to maintain a suitably solemn demeanor. Sikander had seen the reaction more than once. Many Aquilans were simply unsure of how they were supposed to greet him, and couldn’t help but get a little nervous or self-conscious. “Can I get your bag?”

The first of a hundred little decisions that might color how Hector’s crew receives me, Sikander reflected. Kashmir was a little old-fashioned, and a gentleman would never allow a young lady to carry a bag he was perfectly able to carry. On the other hand, an Aquilan officer would not want to suggest that he thought that a female rating couldn’t carry a duffel that a young enlisted person would be expected to tote for an officer . . . and a North would never carry a bag at all, but that was also an impression he would not wish to put forward. He decided that he’d rather look unconcerned about the whole business. “It’s no trouble,” he answered. “Lead the way.”

Hector might have been more than two hundred meters in length, but that didn’t translate into a very spacious interior. Armor, power-plant shielding, drives, weapon capacitors, and space for fuel, water, oxygen, and other necessary stores took up a lot of the hull volume. Officers’ country turned out to be just aft of the ship’s bridge. The stateroom reserved for Sikander’s use featured a decent-sized bunk, a desk and chair, a closet, a sink, and a small couch that faced the desk; as a department head, he rated his own quarters, including enough space to meet privately with a subordinate if needed. A screen on the outward-facing bulkhead showed the busy orbital approaches around New Perth Fleet Base, although it was a video feed from an exterior camera. Overall the room was not much bigger than three meters by six—spacious and comfortable for shipboard accommodations, and certainly a big step up from the tiny cabins he’d shared with other officers in his previous assignments.

Without a word, Darvesh went to work unpacking Sikander’s clothes and hanging them in the closet. Deckhand Parris stared; in all likelihood she’d never seen a valet. Most Aquilan enlisted men and women came from the middle class, after all, and the Commonwealth Navy had a deep-rooted egalitarian tradition. “Thank you, Parris,” Sikander told her. “I think we can manage from here.”

“Yes, sir!” the young woman replied. Curious or not, she recognized a dismissal when she heard one. She saluted and hurried back down toward her watch station at the ship’s hangar.

“Your whites, sir?” Darvesh asked, holding up Sikander’s dress uniform.

“Yes, please.” Hector’s crew wore shipboard jumpsuits for their in-port routine, but to report to a new commanding officer Sikander preferred to err on the side of formality. He quickly changed out of his flight suit, pulling on the clean white tunic and red-striped trousers of an Aquilan officer, and took a moment to splash a little water on his face and check his appearance in the mirror. He always liked the way he looked in his dress whites; the uniform complemented his copper complexion and dark, wavy hair. Those features were common enough in Kashmir, but he also had the North eyes—a striking jade-green hue rare anywhere Sikander traveled. It must have been a good combination, since he rarely had much trouble attracting the interest of the relatively tall and slender Aquilan women he encountered. “Right, I’m off to call on the captain. Why don’t you go get settled in the chiefs’ quarters?”

“As soon as I finish here,” Darvesh replied. “Good luck, sir.”

“Thanks.” Sikander left the tall Kashmiri arranging his shoes in the closet, and set out to find his way to the captain’s cabin. As the petty officer on watch in the hangar promised, he already had access to the ship’s information network; a few quick taps on his dataslate produced a small map to show him the way. One deck up and halfway around the circular main passage, and he was at the captain’s door.

Sikander paused for a moment to collect himself. In theory Captain Markham was fully briefed on his unusual situation, but there was no doubt that it would be awkward for any commanding officer. In his brief naval career he’d already seen resentment, distrust, cold formality, and—the most commonplace reaction—complete bafflement. It all struck him as more than a little unfair, but he’d learned to put up with it because his service in the Aquilan star navy was important to Kashmir. His home was in dire jeopardy of becoming as obsolete as the polearms carried by the guards who paraded in front of the Revered Kathakar’s Palace. Like many of the second-wave colonies established in the early centuries of Terra’s expansion to the stars, the worlds of the Kashmir system had fallen out of contact with the rest of humanity. By the time the Aquilan Commonwealth had reestablished contact, Sikander’s people lagged generations behind less-isolated worlds in technology and industrial development. Kashmir desperately needed a thousand Sikanders—a million Sikanders—to help catch up by taking service with Aquilan corporations, universities, research facilities, and armed forces, learning everything they could. But that didn’t mean Aquilans always welcomed the junior partners in their alliance or regarded them as equals, especially in conservative organizations such as the Commonwealth Navy.

“Easy things are not worth doing,” Sikander murmured aloud—a favorite expression of his father’s. Nawab Dayan North expected that any son of his would work tirelessly to make himself the master of his circumstances. Small obstacles such as growing up in a world decades behind the current technology of the Coalition powers or a wall of institutional discrimination did not matter. Much was expected of a North and a son of the nawab.

I am not doing this for him, Sikander reminded himself. But despite that, he found himself remembering the night he was sent away from home. It was ten years ago now, the night of the Bandi Chor Divas celebration. The Day of Release, ironically enough. He closed his eyes, remembering—

the terrace of the palace at Sangrur, sirens of emergency vehicles keening in the night. The doctors fight to save Mother and Gamand; he waits in the warm night just outside the palace’s medical center, unable to watch. After an hour, Father emerges from the medical center, his face harder than stone.

Sikander fears the worst until Nawab Dayan sighs and speaks: “Your mother will live, and Gamand as well. But I have just been informed that Devindar was attacked at the same time we were.”

“Devindar, too?” Sikander grips the balcony rail to steady himself. His older brother is studying at the university in Ganderbal, not even on the same continent. The KLP means to eliminate all of us, he realizes. “Is he—?”

Nawab Dayan shakes his head, sparing him the rest of the question. “He is not seriously injured. But you must leave for High Albion as soon as possible, Sikander.” It is always “Sikander” when his father addresses him, never “Sikay” or even “son.” “I can arrange for you to join this year’s midshipman class instead of next year’s. We can never all be on the same planet again.”

He stares at his father in horror. “People will call me a coward, Father!”

“This is not a matter for discussion,” Nawab Dayan snaps—a rare failing in a man who habitually keeps his own fierce temper firmly in check. “I will not be defied on this.”

Even though he is only eighteen standard years of age on this awful night, Sikander already knows that It’s not fair! has not the slightest chance to alter one of his father’s decisions. He fights down the urge to say it anyway. “I know nobody at the Academy. And I will be the only Kashmiri there!”

“Nothing has ever been difficult for you, Sikander. A little adversity might teach you something about yourself.” Sikander’s father turns then to set both hands on his shoulders. “This is an opportunity. Our enemies in the KLP are right about one thing: We will not always be tied to the Commonwealth of Aquila. Study hard, do what is right, and remember that you are a North of Jaipur. Make us all proud.”

Standing at Captain Markham’s door, Sikander opened his eyes and brushed away the past. In ten years he still hadn’t found a good answer to his father’s expectations. In his more honest moments, he could admit to himself that Nawab Dayan had been right about what the eighteen-year-old Sikander needed, no matter how much he’d hated it at the time. Now . . . now he could return to Kashmir any time he wanted to, but he’d come to define himself by his chosen profession, not his family name.

This is not about my father or his expectations, Sikander told himself. This is for me, and whether I can be proud of myself. Father was right about one thing—it isn’t supposed to be easy.

He rapped his knuckle on the door.

“Come in,” a woman replied in a firm voice.

Sikander entered. The captain’s cabin doubled as her office and private conference room, much like his own stateroom, but her quarters were large enough to seat half a dozen people at once. There were a few personal touches in sight: a couple of digital images displayed in a frame on the bulkhead, a pair of small viewports that offered a peek at New Perth’s darkening coastline far below, half a dozen small models of older starships (and one seagoing vessel), and, most uniquely, a large oil painting showing an equestrian in traditional riding dress jumping her horse over the water obstacle in a race of some kind. Physical artwork was quite uncommon, especially aboard starships; without meaning to, he allowed his gaze to linger on the painting for a long moment before he remembered himself.

He turned his attention to the officer seated at the desk and saluted. “Lieutenant Sikander North reporting for duty, ma’am,” he said calmly.

“Commander Elise Markham, captain of the Aquilan Commonwealth starship Hector,” she replied, and acknowledged his salute. Captain Markham was a tall, thin woman with short red-brown hair and a deep, tawny complexion, perhaps forty-five years of age. She had stern, dark eyes—unusual for Aquilans, whose eyes usually ran toward a warm brown or hazeland a serious set to her wide mouth. Most Aquilans and citizens of other cosmopolitan powers showed few characteristics of the old Terran races, which had blended together long ago; idiosyncratic phenotypes were usually found among people from more secluded systems. Her lips quirked upward as she took note of his distraction with the painting. “Welcome aboard, Mr. North. Please, have a seat on the couch.”

“Thank you,” Sikander replied. He took a seat in the cabin’s small sitting area, while Captain Markham got up from behind her desk and came to join him, sitting on the opposite couch. He took the opportunity to study her more closely, and looked back to the painting again. “Wait a moment. Are you the rider in the painting, ma’am?”

“You have a sharp eye. Yes, that’s me, although I was only nineteen then. My sister painted it.”

“It’s quite good,” he said, and he meant it. Sikander had seen more real paintings than most people, and he could see that the artist had effortlessly captured the horse in midjump, with the young Elise Markham leaning forward and standing in the stirrups.

“Do you have horses in Kashmir, Mr. North?” Captain Markham asked. It was not a meaningless question; few colonists setting out from Old Terra during humanity’s early migrations had brought horses along for the trip, and even fewer had managed to keep the creatures alive during the hard years most new colonies had faced in the distant past.

“We do, ma’am. I have done a fair amount of riding myself, but nothing like that sort of competitive jumping. Just trail riding.” In fact, one of the North estates in Srinagar offered better than five thousand square kilometers of rugged and beautiful riding on the edge of the Kharan Desert. Sikander had spent a few summers there as a teenager.

“That’s actually an ancient type of race called a steeplechase, not a jumping competition. I used to do some of those, too.” Markham looked at the painting for a moment, and a small grimace passed over her face. “I broke my leg badly just two races later, and never raced competitively again. But I still like to ride every chance I get. Can I offer you some coffee or tea, Mr. North?”

“Coffee, thank you, ma’am.” Sikander was not particularly thirsty, but he very much wanted to make sure that Captain Markham felt comfortable pursuing the interview in her own good time. In Sikander’s experience, some people in authority engaged in small talk simply because they enjoyed the sound of their own voices, while others seemed to sincerely try to put their subordinates at ease at the beginning of a conversation. Elise Markham seemed to be one of latter, which he took as a good sign.

Markham retrieved a pitcher and a pair of cups and saucers from a small wall unit and set them on the low table between the couches. “How are you settling in?”

“Well, thank you,” said Sikander. “This is not my first tour in New Perth. I have quite a few old classmates in-system, and I own a nice condominium in Brigadoon. For now I’m in one of the spare rooms, though. My cousin Amarleen moved in a few months ago while I was off-planet. She’s studying at Carlyle.” Most officers and senior enlisted personnel assigned to ships based in New Perth established homes down on the planet for their families; Brigadoon, the planetary capital, was a popular choice. For Sikander, raising a family was not yet a consideration, but establishing himself in the fleet’s social circles ashore and entertaining friends were things he very much looked forward to. He could keep his boat in the marina and go fishing when he was off-duty, and it was only ten minutes by flyer from the city’s orbital shuttle terminal.

“Carlyle, really?” Markham nodded in appreciation; it was one of the foremost medical colleges in the Commonwealth. “I’m impressed.”

“We all are, although I can hardly tell her that to her face,” Sikander admitted. “She’d be insufferable.”

“Naturally,” Markham agreed, and smiled. She set down her coffee and leaned forward. “Well, let’s get down to business. As you might expect, I have reviewed your service jacket closely. And I’ve also had a conversation with a representative from the Admiralty, and another from the Foreign Ministry.” She gave a small shrug. “I’ve been in the Commonwealth Navy a long time, Mr. North, but I confess that this is the first time I’ve had a diplomatic briefing about an officer serving in my command.”

“I understand, Captain,” Sikander said, setting down his own coffee. “It’s an unusual situation. However, it is my sincere hope that you will treat me exactly like you would treat any of your other officers. I don’t expect any sort of favoritism or prejudice. If I screw up—which hopefully will not be often—I expect to be corrected or reprimanded like any other Aquilan officer.”

“So I was told by the Admiralty, and so I intend to proceed.” Captain Markham studied him. “However, your service jacket suggests differently. You seem to have had a reputation at the Academy, your first shipboard tour on Adept was not terribly successful, and I can’t help but notice that you are quite junior for assignment as a department head. You are taking over for an experienced and well-liked gunnery officer, and I have some . . . concerns.”

Sikander tried not to wince. Fortunately he had been expecting to hear something along these lines, and did not allow himself to become angry or flustered by the sentiment. “I can’t change what is in my service jacket, Captain Markham,” he said. “Yes, I didn’t always take things seriously at the Academy, and yes, I argued with my department head on Adept. I also suspect that the Admiralty is under some pressure to accelerate my career in order to foster good relations with my father—something I certainly never asked for, I should add.” The Commonwealth had figured out long ago that it was easier to exercise influence through Kashmir’s existing aristocrats than it was to build a local administration without their help. As a result, Aquila’s Foreign Ministry placed a high value on the support and goodwill of potentates such as Nawab Dayan . . . which, incidentally, did nothing to endear the North clan to the Kashmiri Liberation Party or any of the other Kashmiri nationalist movements.

“Asked for or not, it’s not the sort of help that is likely to make a favorable impression on your fellow officers,” Markham observed.

“So I have learned, ma’am,” said Sikander. “However, I think you will see that my tour on Triton was much more successful, and I received high marks in Department Head School at Laguna. I’d like to think I have matured a bit in the last couple of years, Captain. I ask only that you base your opinion—for good or for ill—on how I perform on Hector.”

Markham regarded him for a long moment before she answered. “Very well, Mr. North. You begin with a clean slate with me.”

“Thank you, ma’am.” Sikander decided that the captain meant what she said. Of course, what she didn’t say was whether the rest of Hector’s officers would feel the same.

“As I just said, you’re taking over a gunnery department that is running well at the moment. Do you know how you would like to proceed with assuming your duties?”

“I have already started reviewing the service jackets of my personnel—my thanks to the chief yeoman for forwarding them to me at Laguna. As soon as I can, I intend to meet with the division officers and chief gunner’s mates. But what I would really like to do is get in some live-fire exercises and see how the team works together.”

Markham offered a small smile. “A gunnery officer who isn’t interested in shooting is a gunnery officer I have no use for. As it so happens, we have some range time already scheduled for next week. I’ll see if we can add some torpedo practice, too.”

“Thank you, ma’am.”

“Don’t thank me yet, Mr. North. I am a stickler for high range scores.” Markham stood, and offered her hand. Sikander stood and shook it. “If you have any questions or trouble, my door is always open. Make sure you introduce yourself to Pete Chatburn—the XO—soon. He’s running errands planetside right now, but he should be back in a few hours.”

“I will, Captain,” Sikander promised. He saluted again, and turned to go.

“One more thing, Mr. North.” Captain Markham stopped him. “Out of curiosity, just what is the significance of the title Nawabzada of Ishar?”

“Ah. Ishar is the largest continent of Jaipur, the fourth planet in the Kashmir system. It’s the next one out from Srinagar—Kashmir Prime. My father is the nawab, or prince, of Ishar. Nawabzada simply means ‘son of the prince.’ ”

Markham’s calm reserve cracked just a little at that. She blinked. “You are the prince of a continent?” she asked.

“It is mostly a ceremonial title, Captain. I am the fourth-born in my family, and since I am unlikely to succeed my father, I’m expected to find another way to make myself useful. Military service is a traditional alternative, but of course Kashmir’s navy is almost nonexistent, so my father had me sent to Aquila’s naval academy instead.” Sikander offered a small shrug; as much as he might have resented being sent away at first, idleness wasn’t really in his nature. Pursuing a competitive and engaging career helped to make up for ten years of virtual exile. “There are also diplomatic benefits. The Aquilan alliance is vital to Kashmir’s development and will certainly remain so for many years to come. Serving alongside Aquilan officers helps me to appreciate Aquilan interests and traditions, and perhaps meet those who will play an important role in Kashmiri affairs in the future.”

It might also demonstrate to the Aquilan Commonwealth that, while Kashmir was a backward system, it would not always be so, and Kashmiris were every bit as capable as native-born Aquilans if given the education and opportunity . . . but Sikander didn’t feel that he needed to point that out. Many Aquilans held little respect for the peoples who were native to the colonial possessions of the Commonwealth, and harbored a sort of unthinking bigotry toward them. It was not founded on race, since Aquilans themselves represented a mix of many different Terran phenotypes, but there was no doubt that most Aquilans were quite convinced of the superiority of their culture. He hoped that Elise Markham wouldn’t turn out to be that way, or it would be a trying tour of duty for him.

The captain quickly recovered her Aquilan aplomb. “I see,” she said. “For what it’s worth, Mr. North, I look forward to learning a thing or two from your assignment on Hector, too. Carry on.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Sikander replied, and left to get settled in his new home.

Copyright © 2017 by Richard Baker

Order Your Copy

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window

The ebook edition of opens in a new windowValiant Dust by Richard Baker is on sale now for only $2.99! This offer will only last for a limited time, so order your copy today!

The ebook edition of opens in a new windowValiant Dust by Richard Baker is on sale now for only $2.99! This offer will only last for a limited time, so order your copy today! opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window opens in a new window

opens in a new window